Canada's Military of Tommorrow

© Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo, Image ID FF9HM9

Carl von Clausewitz

From an International Strategy to Tactical Actions: How Canada Could Run Campaigns

by Erick Simoneau

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

“No one starts a war – or rather, no one in his senses ought to do so –without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by that war and how he intends to conduct it. 1

– Carl von Clausewitz, On War, 1832

Colonel Erick Simoneau is a tactical aviator currently posted to Canadian Joint Operations Command as Deputy Chief of Staff for Continental Operations. His interest in the Canadian Armed Forces’ mandate was sparked during an assignment to the Chief of Programmes, and the idea for this article came to him during his time attending the National Security Programme course in Toronto, 2015–2016.

Introduction

Canadian politicians generally defend the idea that Canada has earned a seat at the table with the major world powers through its participation in the two world wars, numerous United Nations missions, and, more recently, operations in Afghanistan. However, not everyone agrees with this, and some are critical of Canada’s small military budgets and the lack of clarity regarding its international policy,2 arguing that Canada cannot really be seen as a credible actor on the world stage. Most political experts agree that defence is a discretionary expense that is taken seriously only when economic conditions permit.

This situation does not make things any easier for the senior command of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), which must deal with uncertainty about the size of the budgets it will be allocated for planning its acquisitions and for fulfilling its role in service to the government. Despite that constraint, everyone agrees that our soldiers do what is expected of them very ably, and that they are recognized as one of the most professional and most effective armed forces in the world. In fact, it is very rare for military budget cuts to result directly in a military defeat on the ground.3

This article therefore seeks to bridge the dichotomy between the CAF’s mandate and its budgets, by offering a method of intervention that is Canada-specific and designed to protect Canada’s national interests and values. It is a nationally unifying method that would position Canada as a credible actor within the international community, while taking into account budgetary and geopolitical realities. We will argue that, to achieve this goal, Canada must review its international policies in order to focus them upon specializing in pan-governmental and expeditionary stabilization interventions. That niche role would be Canada-specific and would also be highly valued by the global community.

Our argument will be presented in three sections. The first will look at the current situation and the pitfalls associated with it. The second will discuss Canada’s contribution and the role Canada could play by embracing the possibilities offered by the current context. The third and final section will analyze the ways in which the CAF should position itself within this context by building upon its strengths.

This article is addressed to the CAF senior command, but the recommendations in it cannot be put forward in isolation from the other federal departments or the rest of the political apparatus. However, it does offer a possible solution that would enable Canada to run campaigns at some future date,4 as would any nation that wants to acquire the means to influence its destiny within the world order of today.

“Fire and forget” missions

“Failing to adequately link tactical action to national strategic objectives is both a technical and moral breach of considerable significance, with far-reaching repercussions.” 5

– Colonel Jonathan Vance, Tactics Without Strategy, 2005

DND photo KW04-2016-0048-001

The current Chief of the Defence Staff, General Jonathan Vance (centre)

Canada’s “grand strategy” is not explicitly defined in official government documents. But military historian Desmond Morton sums up its foundations when he speaks of Canadians’ conviction that their country is simultaneously “indefensible and invulnerable.”6 Canada’s propensity to participate in deployments as part of a coalition, forge multilateral alliances and defend the rule of law above all else springs from the knowledge that this country depends on its allies and on respect for international rules to protect its interests. Our alliance with the United States under the auspices of NORAD7 clearly demonstrates this. Some go so far as to say that Canada does not act based on its national interests, but rather in the service of more global interests, in concert with its allies.8 However, that perspective also encourages Canada to view its armed forces as a form of currency to be exchanged. They are deployed in the service of global actors, and in return Canada gains a certain status and a voice among the major powers on international issues.9 Others note that Canada contributes effectively to global interests, but with less than maximum effort.10 We will examine all this more closely.

DND photo FA2013-5100-15 by Corporal Vicky Lefrançois

Canadian CF-18 Hornets from Cold Lake, Alberta, and Russian Su-27A fighters from Anadyr, Russia, practice procedures to transfer a simulated hijacked airplane from Russian to American airspace during NORAD Exercise Vigilant Eagle 13, 28 August 2013.

Colonel Vance—who today is a full general and the CAF’s Chief of the Defence Staff—summarized the situation in 2005: “In general terms, therefore, CF mission success is defined by its tactical presence in a theatre of operations rather than its tactical performance in achieving Canadian strategic objectives.”11 He concluded that Canada does not run campaigns, since it does not decide on the strategic objectives to be achieved.12 In other words, Canada sends its troops overseas under the command of coalitions whose strategic objectives are rarely determined by the Canadian government.13 In military language, we could say that those missions are conducted in “fire and forget” mode, like a missile that, once launched, requires no further action from the firer to reach its target.14

Some defence experts will say that that approach is very flexible, since Canada commits itself only to the extent to which it feels comfortable, while still taking care not to unduly annoy those that guarantee the protection of its interests, especially the United States.15 That enables it to contribute, while economizing on effort and cost.16 Of the G7 countries, Canada invests the least in defence, nor does it rank any better among NATO countries.17 That flexibility also perpetuates a vicious circle that keeps Canada’s military budgets low. Let us now look at how that occurs.

Since the government does not establish specific strategic objectives beyond providing a presence – sometimes referred to as “significant” or “expeditious” – the CAF clearly has a great amount of latitude in the options it presents to the political decision-makers. Often, it will offer only the elements that are available, ready and trained. The CAF is generally recognized for delivering the goods, even as it requests larger budgets to fulfil its mandate.18 That approach may be reasonable for short, simple missions.19 However, it might be quite a different story if the government established specific strategic objectives describing specific tactical performance.20

And therein lies the danger of Morton’s axiom. How can risking the lives of our soldiers be justified if we cannot link their service with concrete strategic objectives decided upon by the Government of Canada? And how can we legitimize such missions and fully communicate them to Canadians if our government does not know the final destination of the “missile” it just fired? Colonel Vance answered that question in the quotation at the beginning of this section. Therefore, we must resolve the paradox of “fire and forget” missions, if only out of a moral duty toward our troops. Disagreements over defence budget expectations must also be settled in the higher interest of our country’s civil–military relations.

Two important deductions follow from the preceding analysis. First, Canadian politicians seem to perceive the CAF as a medium of exchange that requires only a low level of political commitment and whose budgets are always deemed reasonable, as long as the objective of presence assigned to the CAF is achieved. Second, there is clearly a disconnect between the Canadian government’s expectations regarding the employment of its forces and the CAF’s opinion of those expectations, as shown by the divergence of opinions concerning the budgets allocated. We will keep these two conclusions in mind in the following sections. The next section will focus upon the kind of international commitment that Canada might consider in order to fill the moral vacuum described above – that is, to do better than “fire and forget” missions.

“Canada is back”

“Since World War II, some of our most costly mistakes came not from our restraint, but from our willingness to rush into military adventures without thinking through the consequences …. Just because we have the best hammer does not mean that every problem is a nail.”21

– Barack Obama, 2014

© EPA European Pressphoto Agency b.v./Alamy Stock Photo, Image ID FNRYAM

President Barack Obama

There is no better time than the present to rethink the way in which Canada contributes to its security, and the approach it has adopted to do so. The mandate to conduct an in-depth review of Canada’s defence policy presents the perfect opportunity. In addition, the mandate letters sent to Canada’s Minister of Defence and Minister of Foreign Affairs point in the same direction. In both, the Prime Minister sets out the following goals: that Canada engage more in the international community, that it concentrate on peacekeeping missions, and that it carve out a niche in which it can effect real change.22 The withdrawal of the CF18s and their replacement with a training mission in Iraq, together with the announcement of new missions in Lithuania and Africa, are certainly consistent with this new perspective. In this section, we will address the questions of how those decisions should be interpreted, and how Canada’s role in the world can truly be renewed.

DND photo WG2014-0437-0018

A Canadian CF-18 Hornet with two Portuguese F-16s during Air Task Force Lithuania, as part of Operation Reassurance

The Prime Minister’s mandate letters imply (whether based upon a fully informed decision or upon intuition) that recent military operations have not, in themselves, seemed to produce the desired results, and that a more comprehensive approach should be adopted. That point of view is certainly becoming more and more widespread – the Obama quotation at the beginning of this section is one example. Joe Clark, a former Prime Minister of Canada and former Foreign Affairs Minister, makes the same point in his latest book.23 He suggests that, in order to make a more substantial contribution, Canada should combine the use of its armed forces with an approach based on “soft power,” thereby taking advantage of its talent for multilateral efforts.24 The current government’s statement “Canada is back” certainly alludes to it. It also seems that when Prime Minister Trudeau speaks of a return to peacekeeping missions, he is contrasting them with combat missions.25 In any case, there is merit in the idea that missions based exclusively on military strength are insufficient. Any attentive observer will have noticed – as has General Philip Breedlove, former commander of the NATO forces – that the military interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, and more recently in Syria, do not seem to have stabilized those regions.26 The operations did manage to contain the terrorist groups, but they did not solve the real problems; at best, they froze them in time.27

The Canadian Press/Fred Chartrand, Image ID 20140521

Former Prime Minister Joe Clark

Former senator Hugh Segal, who served as Chair of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee in 2006 and 2007, also stresses that military intervention alone is not effective. His new theory is based upon the primacy of two freedoms that must be provided so that a people can live in stability and peace: freedom from fear and freedom from want.28 According to this theory, a person or a people must first feel safe in order for innovation to flourish and bring prosperity. However, Segal adds that this freedom (freedom from fear) cannot be eradicated unless freedom from want is also eliminated. Otherwise, peoples are deprived of all hope and fall back into violence, leading once again to the loss of freedom from fear. Segal is describing a vicious circle. What makes his theory interesting is the cause-and-effect relationship between these two freedoms. For him, solving the problems associated with only one or the other of these freedoms is not enough to lead to a long-term solution.29 In other words, dealing only with safety or development in isolation will lead to failure at the strategic level. Senator Segal’s theory articulates what many people sensed but could not express so clearly.

If one accepts this theory, then the pan-governmental approach should become the favoured option for any future intervention. But is it a new concept? Some would say no, since the terms “3D approach” and “pan-governmental” have been in use for some time.30 However, what has become clear is that this approach is a sine qua non if we want to deal successfully with the most complex situations.31 But did we not already know that? No – if we had, the interventions in Libya and Syria would have been handled very differently. Others refute Segal’s theory by citing the success of the military approach used during the first Gulf War in 1990–1991. The opposing argument is that military force was sufficient to resolve that conflict because the Kuwaitis never really lost hope or exhausted their resources, i.e., their freedom from want. Clearly, Senator Segal’s theory makes a great amount of sense, and it will therefore serve as the foundation for the approach presented in the following pages.

Based upon this theory, we can now make a few important deductions for Canada. First, such an approach would require a unified international policy, since it requires a much more effective integration of the various governmental actors. A defence policy review alone will not be sufficient to bring together all the required stakeholders, but it will be a step in the right direction. However, it must serve as the basis for the formulation of a future international policy – specifically, a unified international policy that will take into account the fact that Canada must no longer intervene without closely examining all aspects of the two freedoms Segal discusses.

Second, it is possible for Canada to make a real contribution to global order if it capitalizes on its strengths and leverages the opportunities that arise. Canada could offer the international community a pan-governmental quick reaction force. Like the United States, which is often perceived as the police or the guardian of the international community, Canada could be its “pan-governmental expeditionary stabilization team.”32 Very few countries have economic and geopolitical situations that would enable them to do this successfully. Canada does, and it would have much to gain by making good use of those assets.

This approach would require a review of the priorities of the roles assigned to Defence and the other departments that deal with world affairs. For more than 40 years, the priority has been the defence of Canada, then that of North America, and lastly, peacekeeping and maintaining stability in the world.33 Instead, the government should prioritize the CAF’s expeditionary capabilities. Many experts believe, like David Bercuson and Jack Granatstein, that “Canadian governments … have believed that one key mission of the Canadian military is to deploy abroad….”34 However, this new priority should not be seen as contradicting those that are already established. The next section will shed light on this point.

Lastly, it is interesting to note the differing points of view concerning the right role for the CAF. These divergences of opinion also explain the mutual incomprehension that results when expectations confront defence budgets.

The Canadian Method of Intervention

“Canada is a fire-proof house, far from inflammable materials.”

– Senator Raoul Dandurand, speaking before the Assembly of the League of Nations, 1924

Library and Archives Canada/C-009055

Senator Raoul Dandurand, (third from left), at the League of Nations Assembly in Geneva, September 1928

The analysis presented in the previous two sections of this article reveals some inconsistencies between the current defence policy and the way in which the CAF is employed. In the first section, we established that Canada appeared to use its armed forces as a form of currency, offering its presence in exchange for a voice in international affairs. We also concluded that this way of doing things makes it more difficult to legitimize “fire and forget” missions in the eyes of Canadians, and especially in the eyes of CAF members themselves. In the second section, we demonstrated that exclusively military interventions often do not meet the strategic expectations set by the international community. We then suggested that Canada could become more actively involved by taking on the niche role of providing pan-governmental expeditionary and stabilization power for the international community.35 In the final section, we will explore how the CAF could position itself within the international community, and could even become its leader.

As we have seen, the Canada First Defence Policy, which has been in effect since 2008, establishes the CAF’s roles: defend Canada, protect North America, and participate in peacekeeping and maintaining stability in the world.36 There is no doubt that the CAF’s priority must always be to defend Canada. However, that does not mean that the CAF could not also play the role of an expeditionary force.37 One does not necessarily preclude the other. In the next defence policy, we would do well to transform the current roles into “intervention priorities” in order to leave room for discussion about the best ways to implement them. An expeditionary force could be deployed to defend Canada, protect North America, or intervene overseas. It is its composition and mandate that should change, not its intervention priorities.

The CAF already possesses a considerable amount of expeditionary equipment that is the envy of many countries. The C17s are a good example. The CAF should continue in this vein by shedding its non-expeditionary structure, then by dedicating the positions and budget amounts freed in the process to expeditionary and pan-governmental initiatives. Note that, for the purposes of this article, all the CAF’s operational capabilities are considered as expeditionary. We are more concerned here with their role and the structure that supports them.

DND photo NB01-2016-0104-005 by Corporal Rob Ouellette

A Canadian C-17 loading US air defence equipment on Exercise Vigilant Shield, 13 August 2016.

In fact, it is the CAF’s geographic rather than its functional structure that should be re-examined. But if we accept the idea that even the defence of Canada must be undertaken in concert with its allies, the CAF should stop insisting upon structuring and equipping itself for handling it alone. That is exactly the kind of measure that Canada should consider in order to eliminate all the non-expeditionary tasks and structures for which the Department of National Defence establishes its activity plan and its expectations regarding budgets. CAF expeditionary forces would contribute much more effectively to the defence of Canada and of North America if Canada provided its principal ally, the United States, with a pan-governmental expeditionary stabilization force, rather than trying to reproduce the same operational capabilities that the United States possesses. That could become the “Canadian method of intervention,” a method that would be useful for both defending Canada and intervening overseas. The idea of a niche role is even more attractive given that, in the short and medium term, defence budgets will probably remain where they are now in relation to gross domestic product (GDP). Focusing upon expeditionary capabilities would be an excellent way to balance expectations with the CAF’s roles and budgets.

A Canada engaged in the world and occupying its own specific intervention niche will also be able to (and will have to) formulate its own strategic objectives for intervention. By doing so, it will also put an end to “fire and forget” missions. To achieve that, Canada should always take ownership of the portions of a coalition campaign upon which its departments will be able to work together under a single flag – that of Canada. The operational capabilities deployed could certainly also work as part of a coalition, as long as they do so for the advancement of the strategic objectives set by Canada. It is the strategic objectives that must be brought together under one flag, rather than the tactical employment of deployed expeditionary capabilities.

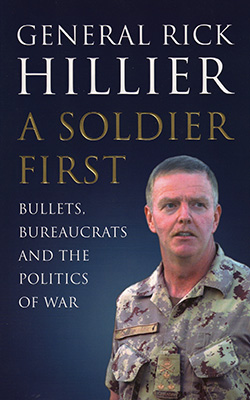

If Canada can accomplish all this, thereby meeting an ever-growing need, it will gain the desired appreciation and recognition from other countries, since few of them will have the agility to do likewise, or even be capable of attempting to do so. That is one of the lessons that General Rick Hillier emphasized in his book A Soldier First.38 For this purpose, Canada should define an area of responsibility (AOR), which may be physical or functional. In Afghanistan, Canada’s AOR was physical when its forces were operating in Kandahar Province. A functional AOR might be the reconstruction of a country’s roads and electrical network. These examples suggest an interdepartmental intervention that begins with formulating SMART strategic objectives.39 Those objectives would be formulated jointly by the departments called upon to act, then presented to the ministers’ offices for approval. Then, clear strategic communications could be produced that would make it easier to legitimize Canada’s operations in the eyes of its forces and the Canadian people.

However, as things currently stand, Canada is not structured, equipped or trained to run campaigns that way, except perhaps in relatively simple humanitarian operations such as sending DARTs to disaster zones.40 That level of integration will not be possible without an international policy and an interdepartmental committee that is responsible and accountable. The CAF could be the promoter and leader in this area, especially where the required expeditionary equipment and training are concerned. France is an example. In a recent article, Michael Shurkin, a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation, convincingly describes that nation’s progress, contrasting the French expeditionary approach with the U.S.’s more traditional approach.41 However, France’s situation is not as favourable as Canada’s, and Canada should seize the opportunity to act. In addition, the idea of specializing and adopting a niche role, as we have described in this article, dovetails very well with the concept of “smart defence” proposed by NATO Headquarters.42 For that reason, it should be taken seriously by our political decision-makers, if Canada truly wants to become a leader in the international community.

Critics of such an approach will undoubtedly say that this method is not part of Canadian culture, and that it would therefore be very difficult to implement, since it would reduce the resources available for ensuring Canadian sovereignty. But we have already taken a step in that direction by ratifying the NORAD treaty. Our CF18s play a niche role as the first interception force, while the United States handles subsequent interceptions and counter-attacks with its fleet of bombers (aircraft that Canada does not possess). There is already a precedent for a niche role, and our territorial sovereignty has not suffered from it in the least.

Others will say that budget allocations and the ministers’ accountability do not currently lend themselves to pan-governmental operations. That is a valid argument. However, an inter-departmental committee led by the Prime Minister could easily fill that gap by ensuring that all intervention decisions would be made by the highest executive level of government.

Lastly, many will say that the geographic structure of the CAF is an incontrovertible fact of Canadian political reality. That is also true. However, this article does not advocate closing bases, but rather, modifying the mandate of the higher headquarters, especially the regional headquarters. Those headquarters would have much to gain if they were given a mandate that was more focused upon expeditionary and pan-governmental operations than it is at present.

Any new approach inevitably brings its share of challenges. However, the facts set out here justify taking a new path. The government has asked for it, and the full review of Canada’s defence policy opens the door wide. The time is right to seize the opportunity.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to reconcile expectations of the CAF and its role with the political commitment and budgets required to ensure the security of Canada’s national interests. We took into consideration today’s economic and geopolitical context and came to the conclusion that the time has come for DND to advocate for Canada to make a more active commitment on the world stage through its new defence policy. In doing so, Canada should turn away from traditional “fire and forget” missions in favour of a strong role in pan-governmental expeditionary stabilization. This niche is one that very few countries can fill.

Becoming the pan-governmental expeditionary stabilization team for the international community would attract the recognition that governments have always wanted to obtain through the CAF. The Canadian government could then affirm that “Canada is really back.” This unifying project would undoubtedly revive the international community’s former admiration for Canada. A commitment of this kind on the part of the Government of Canada would also encourage greater interdepartmental cooperation. Lastly, this “Canadian method of intervention” would also have the advantage of aligning CAF budgets with tangible strategic results, rather than outputs, as is currently the case. Canada could then say it is a country capable of running campaigns in the service of world peace and stability, which would contribute directly to the protection of its own national interests. From an international strategy to tactical actions: that is how Canada could run campaigns.

DND photo by Corporal Peter Ford

Notes

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, translated and edited by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (New Jersey: Princeton, 1976), p. 579.

- In this article, “international policy” encompasses defence policy, foreign policy, and security policy. See Janice Gross Stein and Eugene Lang, The Unexpected War: Canada in Kandahar (Toronto: Viking Canada, 2007), p. 139.

- Expression used in this article in the same sense as “on operations.”

- The expression “military campaign” refers to the entire range of operations and activities carried out to achieve strategic objectives. In this article, the expression “run a campaign” is used in a broader sense. It encompasses some activities that are non-military but still governmental, including but not limited to diplomacy, development, humanitarian aid, and the training of police forces.

- Jonathan Vance, “Tactics Without Strategy,” Chapter 8 in The Operational Art: Canadian Perspectives, Allan English, Daniel Gosselin, Howard Coombs and Laurence M. Hickey (eds.), (Kingston, ON: CDA Press, 2005), p. 273.

- Desmond Morton, A Military History of Canada, 5th edition. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2007), p. xi.

- North American Aerospace Defence Command.

- David McDonough and Tony Battista, “Fortress Canada: How much of a military do we really need? In iPolitics, 27 April 2016, at http://ipolitics.ca/2016/04/27/fortress-canada-how-much-of-a-military-do-we-really-need.

- James Eayrs, “Military Policy and Middle Power: The Canadian Experience,” in Canada’s Role as a Middle Power, J. King Gordon (ed.), (Toronto: Canadian Institute of International Affairs, 1965), p. 84.

- Joel J. Sokolsky, “Realism Canadian Style: National Security Policy and the Chrétien Legacy,” in Policy Matters 5, No. 2, June 2004, p. 3.

- Jonathan Vance, p. 273.

- Ibid., p. 289; and Bill Graham, The Call of the World (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016), p. 361.

- Christian Leuprecht and Joel Sokolsky, “Defense Policy “Walmart Style”: Canadian Lessons in ‘Not-So-Grand’ Grand Strategy,” in Armed Forces and Society, July 2014, p. 544.

- See the discussion on this theme in David P. Auerswald and Stephen M. Saideman, NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

- Joe Clark, How We Lead: Canada in a Century of Change (Toronto: Random House, 2013), Chapter 9.

- David G. Haglund and Stéphane Roussel, “Is the democratic alliance a ticket to (free) ride? Canada’s ‘imperial commitments’ from the interwar period to the present,” in Journal of Transatlantic Studies 5, No. 1, p. 11.

- Roland Paris, “Is Canada Pulling Its Weight in NATO?” in Center for International Policies Studies (blog), at http://www.cips-cepi.ca/2014/05/09/is-canada-pulling-its-weight-in-nato/.

- Philippe Legassé and Paul Robinson, Reviving Realism in the Canadian Defence Debate (Kingston, ON: Queen’s University Press, 2008), p. 57.

- Term used in contrast to more complex operations that require the achievement of specific, concrete strategic objectives in order to meet the government’s political expectations. They are small-scale, low-risk missions.

- Bob Rae, What Happened to Politics? (Toronto: Simon & Schuster, 2015), p. 118; and Tami Davis Biddle, Strategy and Grand Strategy: What Students and Practitioners Need to Know (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College Press, 2015), p. 59.

- Barack Obama, Remarks by the President at the United States Military Academy Commencement Ceremony. West Point, NY: U.S. Military Academy–West Point, 2014, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/05/28/remarks-president-united-states-military-academy-commencement-ceremony.

- Minister of National Defence Mandate Letter, in Office of the Prime Minister, Ministerial Mandate Letters (Ottawa: Canada Communication Group, 2016), at http://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister-national-defence-mandate-letter.

- Joe Clark, p. 33.

- Ibid., p. 159.

- Roy Rempel, “Mr. Trudeau’s Touchy-Feely Approach to War,” in iPolitics, 9 February 2016, at http://ipolitics.ca/2016/02/09/mr-trudeaus-touchy-feely-approach-to-war/.

- Hugh Segal, Two Freedoms (Toronto: Dundurn, 2015), Chapter 4.

- Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote in 2014 that “in only one of the five wars America fought after World War II (Korea, Vietnam, the first Gulf War, Iraq, and Afghanistan), the first Gulf War under President George H. W. Bush, did America achieve the goals it had put forward for entering it .…” The quote clearly demonstrates the inadequacy of military power alone. Henry Kissinger, World Order (New York: Penguin, 2014), p. 328.

- The senator uses two of the four freedoms identified by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a 1941 address to the nation. Hugh Segal, Two Freedoms (Toronto: Dundurn, 2015), Chapter 1.

- Ibid., Chapter 4.

- Wesley K. Clark, Don’t Wait for the Next War (New York: PublicAffairs, 2014), p. 179; and Peter Langille, “Re-engaging Canada in United Nations Peace Operations,” Policy Options = Options politiques, 10 August 2016, at http://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/august-2016/re-engaging-canada-in-united-nations-peace-operations/.

- Term used in contrast to very simple or very short-term tactical operations that do not require concrete strategic objectives.

- Term coined by the author.

- Minister of National Defence, Canada First Defence Strategy (Ottawa: Canada Communication Group, 2007). In the 1970s, Defence also had a separate role as a member of NATO, as noted by James Fergusson, Ph.D, “Time for a New White Paper?” in On Track, Autumn 2015, p. 46.

- David J. Bercuson and J.L. Granatstein, “From Paardeberg to Panjwai: Canadian National Interests in Expeditionary Operations,” in Canada’s National Security in the Post 9-11 World, David S. McDonough (ed.), (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012), p. 193.

- A “stabilization” force would be designed and equipped to intervene in defence of both freedoms: freedom from fear and freedom from want.

- Minister of National Defence, Canada First Defence Strategy (Ottawa: Canada Communication Group, 2007).

- The term “expeditionary” is used in this article to describe the projection of a self-sustaining force using Canada’s own strategic transportation capability. Expeditionary forces can be deployed in Canada as well as abroad. Therefore, the term “expeditionary” should not be associated only with foreign deployments.

- Rick Hillier, A Soldier First: Bullets, Bureaucrats and the Politics of War (Toronto: Harper Collins, 2009), p. 155.

- Method recommended by the Treasury Board of Canada at http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/psm-fpfm/learning-apprentissage/ptm-grt/pmc-dgr/smart-fra.asp can also be found at https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/dpr-rmr/2011-2012/tbd/tbd12-eng.asp. The acronym SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Trackable/Time-bound.

- DARTs: Disaster Assistance Response Teams.

- Michael Shurkin, “What It Means to Be Expeditionary: A Look at the French Army in Africa,” in Joint Force Quarterly, No. 82, July 2016, at http://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ/Joint-Force-Quarterly-82/Article/793271/what-it-means-to-be-expeditionary-a-look-at-the-french-army-in-africa/.

- Peter Langille, “Re-engaging Canada in United Nations Peace Operations,” in Policy Options = Options politiques, 10 August 2016, at http://policyoptions.irpp.org/fr/magazines/aout-2016/re-engaging-canada-in-united-nations-peace-operations/.