Book Reviews

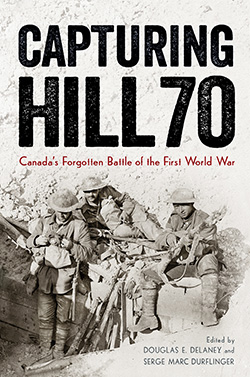

Capturing Hill 70: Canada’s Forgotten Battle of the First World War

by Douglas E. Delaney and Serge Marc Durflinger (Eds)

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016

xii+273 pages, $34.95 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9780774833592

NOTE: Other contributors include Tim Cook, Robert Engen, Robert T. Foley, Nikolas Gardner, J.L. Granatstein, Mark Humphries and Andrew Iarocci.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Reviewed by John R. Grodzinski

Perched between the iconic victory at Vimy Ridge and the horror of Passchendaele, the capture of Hill 70, and the subsequent struggle to take the French industrial town of Lens, are hardly known to Canadians. In August 1917, the Canadian Corps achieved a costly, albeit victorious battle that was as innovative in execution as its earlier assault on Vimy Ridge. Capturing Hill 70 restores Hill 70 to a rightful place among the great victories of the Canadian Corps. The nine essays presented in this volume, each written by a prominent Canadian historian, and each exploring different topics, achieve that goal. The originality of these studies and the quality of their scholarship places Capturing Hill 70: Canada’s Forgotten Battle of the First World War, with the best historical titles to appear during the centenary of the Great War.

The struggles for Hill 70 and for Lens stemmed from the British success at Messines in June 1917 and the Third Battle of Ypres, the Flanders offensive that opened in the following month. Field Marshal Douglas Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, proposed a breakout from the Belgian coast that would initiate a German collapse. The British First Army, which included the Canadian Corps, was directed to prevent the enemy from reinforcing the defenders facing the main British offensive to the north, by taking Lens and threatening Lille. Lieutenant General Arthur Currie - whose knighthood was announced in the January 1918 Honours List - the recently appointed commander of the Canadian Corps, whose task was to take the city, disliked his army commander’s plan for the Canadians to take Lens head on. Instead, Currie won approval for his proposal to take Hill 70, an important feature north of the city, that should make the German position in Lens untenable. It is this audacious opposition to his superior’s orders that set the die for Currie’s reputation as a bold, innovative commander, who personified Canada’s growing independence in the Empire. Three weeks were then devoted in preparation for the offensive.

In a masterfully planned and well-executed attack that commenced on 15 August 1917, the Canadians speedily sliced through the defenders, and over the next three days, the corps lost nearly 1,900 men killed and wounded, as it withstood repeated German counterattacks. It was an exquisite tactical victory. Attention then turned to Lens. Instead of conforming to British and Canadian estimates that the Lens would have to be evacuated once Hill 70 was lost, the enemy stayed put, and turned the hastily prepared and haphazardly executed Canadian assault against a built-up area - terrain the Canadians had little experience with - into a costly failure. Unable to gain the final objective by the time the offensive was ended on 25 August, the corps’ victory at Hill 70 became less complete than Vimy Ridge, and it soon faded into obscurity, as the Germans retained control of Lens until the following spring.

The essays in Capturing Hill 70 explore command (relations between the commanders of the First Army and the Canadian Corps, divisional commander, formation staffs and staff procedures; and assess Currie as corps commander), the employment of specific arms and services (chemical weapons, indirect fire weapons, transportation and supply, medical services), politics and manpower, and the heritage of the battle. The originality of the topics is evidenced in phrases, such as previous ‘lack of attention that has been paid’ (p. 31) to a particular subject, or the failure to give these two battles ‘serious scrutiny’ (p. 78) can be applied to every chapter. There is a lot of new material presented in these pages.

‘The Best Laid Plans: Sir Arthur Currie’s First Operations as Corps Commander,’ by Mark Osborne Humphries, is an excellent examination of Arthur Currie’s performance in this campaign. Nationalist historians and commentators present Currie’s bold critique of his superior commander’s plans, and the Canadian Corps Commanders’ achievement in convincing General Sir Henry Horne, of the advantages that would follow by taking Hill 70 first, as indicators of the growing independence on the part of the Canadian Corps, and as evidence of some nascent Canadian ‘way of war.’ Others emphasize the growing professionalism of Currie, a simple colonial militia officer, who rose against the grain to corps-level command, against the stultified social elitism of the British officer corps. Humphries convincingly tempers this nationalist hubris. Currie did willingly ‘voice his opinions to more senior officers,’ and did ‘articulate his point’ (p. 98) in a masterful way, yet his inexperience resulted in an over-optimistic assessment that Lens would succumb without a fight, once Hill 70 was lost to the defenders. Currie revealed ‘…himself to be as vulnerable to the lure of a prestigious objective as many other Great War commanders’ (p. 98), and supported a direct attack against the enemy’s main defences: the failed attack on Lens cost the Canadian Corps 1,154 casualties. Nonetheless, Currie exhibited qualities that once honed, would make him a fine corps commander.

Another Canadian ‘victory’ appears in a chapter by historian Andrew Iarocci entitled ‘Sinews of War: Transportation and Supply.’ The innovative use of narrow gauge railway to overcome shortages in motor transport, which allowed the Canadian Corps to move guns and shells, replenish units and evacuate casualties, invited complaints from Horne’s First Army and Haig’s General Headquarters. The construction and operation of light duty narrow gauge rail lines, so the staff reminded the Canadians, rested with General Headquarters. The Canadian Corps, they continued, was permitted to build their own rail lines so long as the rolling stock was pulled by horses, or pushed by men, a situation that made the transport of heavy shells difficult, and the movement of guns impossible. Currie’s cogent response that rail schedules imposed by rear echelon timetables rather than tactical exigencies endangered the troops, won him approval to continue operating the lines using steam and coal locomotives, rather than with equine or human power. This important victory, somewhat less spectacular than the Canadian Corps commander’s success in taking on an army commander, was one many encounters that reveal the growing skill of the Canadian commanders and staffs in the employment of the combat arms and services. Novel practices in logistical operations, mature command skills, good staff work and admirable fighting skills were hallmarks of the Canadian Corps in 1917, but to equate these qualities with the tools of nation building or independence exclusively distorts the reality of the period.

As revealed in Capturing Hill 70, the unique characteristics of the Canadian Corps - the permanent affiliation of its four divisions, the four battalion structure of the infantry brigades, and the extra artillery brigade at the corps level - did not diminish that fact that the Corps was an integral part of a larger Imperial army, the British Expeditionary Force. The Canadians and their Imperial brethren shared common staff procedures, training methods, equipment, weapons and dress, artillery staff procedures, and many of the same values. British officers also filled several command and many key staff positions throughout the corps. This is not to diminish the achievements of Canadian soldiers. Rather, it reinforces the fact that the young Dominion was a ‘card-carrying’ member of the British Empire, and that Canada was a willing participant in the Empire’s struggle in the Great War. It may seem paradoxical that the supposed birth of Canadian independence resulting from the Great War came not from the ashes of Imperial sentiment. Hill 70 was one of many battles that stirred these ideas in Canadians.

As historian Doug Delaney notes in the introduction, Canadians are largely unaware of the events at Hill 70. The responses to an informal survey he conducted among 20 friends and family members to name battles from the First World War included the names of well-known battles: the Somme, Vimy Ridge, and Passchendaele. No one mentioned Hill 70. This book corrects the lack of attention historians have given to Hill 70, and brings the story to the reading public. Capturing Hill 70 recovers ‘some missing parts’ (p. 26) of the historical record and give full justice to the tens of thousands of Canadians who fought at Hill 70. A related initiative, undertaken by the Hill 70 Monument Project (http://www.hill70.ca/) - which provided financial assistance towards the publication of Capturing Hill 70 - will open a monument in 2017 to the memory of Canadian soldiers who fought and died at Hill 70.

Capturing Hill 70: Canada’s Forgotten Battle of the First World War is a thought provoking book worthy of attention. By casting new light on this important battle and offering new perspectives on the leadership of Arthur Currie and the operations Canadian Corps, it makes an important contribution to our understanding of an important period of Canadian military history.

Major John R. Grodzinski, CD, Ph.D, is an Associate Professor of History at the Royal Military College of Canada.