Personnel Issues

DND/MARPAC Imaging services photo/XC06-2018-0001-126

Women Serving in the Canadian Armed Forces: Strengthening Military Capabilities and Operational Effectiveness

by Barbara T. Waruszynski, Kate H. MacEachern, Suzanne Raby, Michelle Straver, Eric Ouellet, and Elisa Makadi

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Dr. Barbara Waruszynski, DSocSci, is a Defence Scientist with Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis, Department of National Defence, and she specializes in diversity and inclusion research for the advancement of Defence and Security. She is leading two research projects on the recruitment and employment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Ms. Kate H. MacEachern, MA, Ph. D (candidate), is working under the Federal Student Work Experience Program with the Department of National Defence. She is supporting the research on the recruitment and employment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Lieutenant-Colonel (Ret’d) Suzanne Raby joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 1980, and was in the first class of women to graduate from the Royal Military College of Canada. In addition to holding positions across Canada and internationally, she recently led the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group Tiger Team to increase the enrolment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Ms. Michelle Straver, MASc, leads the Regular Force Modelling and Analysis Section in the Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis, Department of National Defence, and conducts modelling and analysis in support of the Canadian Armed Forces’ Employment Equity goals, as well as various other aspects of the Canadian military personnel system.

Major Eric Ouellet, MA, provided support for the research with respect to the recruitment and employment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces. In 2018, he was posted to the Canadian Army as the Canadian Army Primary Reserve Personnel Selection Officer.

Ms. Elisa Makadi is a Master’s student who worked under the Federal Student Work Experience Program with the Department of National Defence. She provided support with respect to the recruitment and employment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces, and currently, she provides counselling services in the private sector and academia.

Introduction

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) has a mandate to increase the representation of women to 25.1% by the year 2026. With the current rate at 15.5%, attempting to increase the representation of women remains an important goal.1 There are several principal reasons why attracting more women to join the CAF remains an important objective for the Canadian military. As women make up slightly over 50% of the Canadian population, they represent a large resource of highly qualified and skilled people who would benefit the CAF. Furthermore, diverse ideas and perspectives can foster new and different ways of thinking. At the core, attracting and retaining women to join the CAF goes beyond politics and employment equity: it is about strengthening military capabilities and operational effectiveness.

The purpose of this article is to examine how the military can serve as a viable and important career option for women. The first section presents a historical perspective on women serving in the CAF, and will outline historical events and trends that led to the involvement of women in the Canadian military. The next section describes the experiences of women currently working in the Canadian military and the main challenges impacting them. The experiences and issues presented in this article stem primarily from the findings associated with three reports: the Earnscliffe Strategy Group study on women in the Canadian public,2 the Waruszynski, MacEachern, and Ouellet (2018) study with respect to the perceptions of Regular Force women in the CAF,3 and the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group Tiger Team (CFRG TT)4 study of the recruitment of women in the CAF. The Earnscliffe Strategy Group’s (2017) study was conducted on behalf of the Department of National Defence (DND) to primarily understand the perceptions of women in the Canadian public, and how they regard a career in the military. The Waruszynski et al. (2018) study was based upon focus groups with women currently serving in the CAF for the purpose of better understanding the attraction, recruitment, employment, and retention of women in the Canadian military. Finally, the CFRG TT (2017) study was based upon the findings of four working groups to help assess the issue of recruiting women into the CAF. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion of the recommendations with respect to how the CAF can move toward a more integrated, diverse, and inclusive Canadian military. This article will give the reader a better understanding of the history of women serving in the Canadian military, what women are currently experiencing as members of the CAF, and the direction that the CAF needs to consider to further strengthen its military capabilities and operational effectiveness.

Historical Perspective of Women Serving in the Canadian Military

History is rife with stories of female heroines on the battlefield, and Canada’s history is no exception. Women have played an important role in military history since the 19th Century, and continue to actively participate in a variety of roles. The first formal participation of Canadian women in a military force occurred during the North-West Rebellion of 1885.5 Growing from an initial nursing staff of one single woman, a small corps of nurses was assembled and dispatched to two field hospitals in the province of Saskatchewan.6 Overall, 12 women endured the same conditions and dangers as those on active combatant service.7 Although they were dismissed from the military once the conflict was resolved, all the women involved were awarded the North-West Canada Campaign Medal in recognition of their service.8

At the turn of the 20th Century, the Canadian government agreed to offer medical services to British Forces, and were overwhelmed with volunteers to act as nursing sisters. A select group of eight nurses was sent overseas by the end of 1899,9 and each nurse was given the rank of lieutenant, with commensurate pay and allowances. As a result of this conflict, the need for a permanent Canadian military nursing organization became apparent, and a Permanent Active Militia Army Medical Corps was created.10 These women were designated as nursing sisters and had no authority or military command, but did benefit from the same pay and allowances as lieutenants.11

DND/Library and Archives Canada/PA-001305

A Canadian Voluntary Aid Detachment ambulance driver at the front, May 1917.

With the eruption of the First World War, an order to mobilize nurses came swiftly.12 Thousands of Canadian women volunteered, with over 2800 of them joining the Royal Canadian Medical Corps.13 Many women had no previous military training before boarding the trans-Atlantic ship and received lectures during the voyage.14 At the end of the First World War, women returned to civilian life, although many joined service-minded organizations, such as the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment.15 The drawdown was significant, and by the start of the Second World War in 1939, there were only 10 nursing sisters and one matron in the Regular Force, augmented by a further 331 women on the Reserve List.16

DND/Library and Archives Canada/PA-001291

Canadian nurses, May 1917.

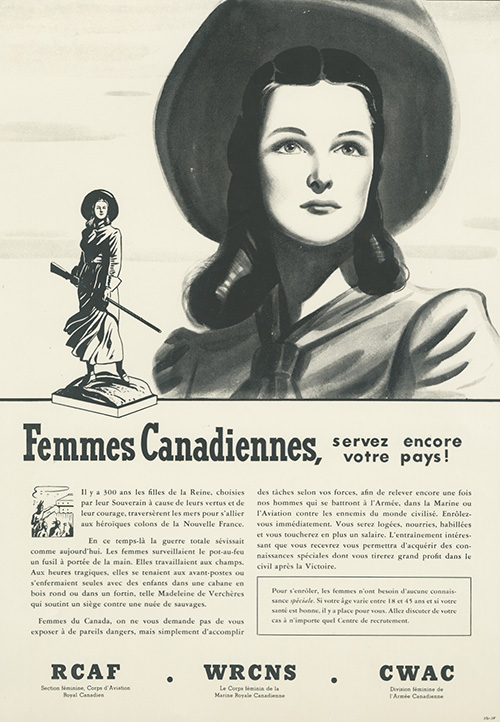

At the onset of the Second World War, women were still viewed as best suited for nursing roles. The perception was that women in military service would not only lead to social disruption, but would also be attributed to the squandering of limited defence funding.17 However, as demand for personnel exceeded the number of male recruits, women were necessary to help shore up military capabilities. In response, the Canadian Women’s Armed Corps, the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, and the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service were formed.18 Each organization allowed women to serve in roles other than health care, so that men employed in non-combatant roles could be made available to fight.19 Of the 102 trades available at that time, 65 were open to women, with the caveat that they would be prohibited from taking on a combat role.20 Most of these women were employed in ‘traditional’ fields, including 5000 female nurses, and received less pay, less benefits, and, in some cases, had a separate system of rank and regulations.

Wartime Recruiting Poster/Canadian War Museum/CWM 19880069-865

Affiche de recrutement en temps de guerre/Musée canadien de la guerre/CWM 19890086-751

Altogether, almost 50,000 service women were employed during the war years, permeating all aspects of military life.21 With the cessation of hostilities in 1945, demobilization plans were made and activated. While all three services recognized the need to maintain a small number of women in uniform, the government was firmly opposed, with the exception being made for nurses, who continued to provide care to injured veterans.

DND/CFJIC/photo ZK-273

With the start of the Cold War and the concurrent outbreak of hostilities in Korea in the 1950s, Canada re-evaluated its posture with respect to women in the military and re-established female service organizations with limits being set as to the maximum number of women allowed into the Regular Force.22 Women served in both clerical and technical positions, and for the first time, received equal pay to their male counterparts. However, certain restrictions were placed on women’s employment. For instance, terms of service dictating the length of time a woman was required to serve were shorter than those established for their male counterparts.23 Women were also restricted to occupations for which training was less than 16 weeks,24 and which were in a lower pay scale than traditionally male-dominated areas.25

In 1971, following on the heels of the unification of the three services into the Canadian Forces (CF), The Royal Commission on the Status of Women made important recommendations with respect to the future of women in the CF.26 As a result, women joining the CF encountered the same set of enlistment criteria and pension benefits as men. Furthermore, the doors of the Canadian Military Colleges were to be opened to women, married women were given the right to enlist, and pregnant women were permitted to remain in uniform. The only recommendation that was not accepted at the time was the opening of all occupations to women. During this time, the military believed that for operational reasons, specific positions should only be filled by men.

Another legislative milestone took place in 1978 when the Canadian Human Rights Act came into effect, forbidding discrimination based on gender (among other criteria), unless for a bona fide occupational requirement.27 The Service Women in Non-Traditional Environment and Roles (SWINTER) trials, which ran from 1979-1984, evaluated women’s ability to function in “near combat” units and was seen as a positive step forward.28 This was also the case for women at sea and within the Air Force environment. For the first time, women were also sent to the High Arctic to work at Canadian Forces Station Alert; and starting in 1980, women donned the characteristic scarlet tunics at the Royal Military College of Canada. Thus, the only barrier to full integration was the employment of women in combat. In 1985, the Equality Rights section of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms came into effect. In response, the CF began the Combat Related Employment of Women (CREW) trials that ran from 1987 to 1989, with the goal of evaluating the operational effectiveness of mixed gender units that engaged in direct combat.29 At the conclusion of the trial, Canadian women were eligible to serve in any military occupation for which they were motivated and qualified, making Canada one of the first in the contemporary western world to promote gender integration.

DND/CFB Kingston photo.

Female cadets have been enrolled at the Royal Military College of Canada since 1980.

Since the removal of systemic barriers to service in the late-1980s, women have worked side by side with their male counterparts, participating in every major military operation around the globe, sharing the same hardships, and celebrating the same victories. Since 2000, nearly 10% of Regular Force personnel deployed on operations have been women, including significant operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. During the same time period, women accounted for approximately 13% of the Regular Force.30 This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the fact that a relatively large proportion of those who were deployed came from combat arms occupations, in which women have a low representation rate. Contemporary military efforts have been sustained by many women fighting alongside their male colleagues and supporting their fellow service members.

The introduction of women into the Canadian military has a long and storied past. Although the CAF has come a long way since the first woman served as a nurse with the North-West Rebellion, there remains a long road ahead. The mandate to achieve a representation rate of 25% requires attention to the current state of integration, and a clear understanding of the ways in which change must occur. The CAF is an organization that supports and encourages the success of women in its ranks, and tries to ensure that the legacy of all women who have served Canada and Canadians alike continues to live on.

Women’s Experiences and the Military Culture

Although women have been a part of military life for centuries, women serving in the military today still face barriers to true integration. As women represent a valuable and skilled sector of the workforce, the military is making an effort to identify the ways in which it can foster an inclusive environment that is welcoming and attractive to women. As part of this mission, the CAF has commissioned a number of research studies to look specifically at the experiences of women serving in the Canadian military.31, 32 The results of these studies have brought to light important issues that need to be addressed if the CAF wishes to move forward in its quest for increasing the representation of women in the Canadian military. These issues centre upon the warrior culture, family life, career progression, harassment, standards, and basic necessities.

The Warrior Culture

The warrior is an ancient notion that takes on great meaning upon the battlefield. It is someone who, in battle, is seen as strong, relentless, brave, heroic, and, often, someone who is male. This warrior motif underscores the commonly-drawn connection between soldiers and masculinity. For women, this conceptualization of a soldier can create a difficult environment in which to thrive. Naturally, there are women for whom this is not an issue, and who view themselves as a sailor, soldier, and aviator first and foremost, with no separation between their identities. However, for many, it is a challenge to be both a woman and a serving member.

This challenge is compounded by the fact that many women are criticized, regardless of their action, and feel that they need to adopt a masculinized way of being and fitting into an “old boys’ club.”33 As a way to fit in with their male colleagues, some women try to minimize their femininity in favour of a persona that is more in line with a masculine portrayal of a serving member. This may mean taking on male characteristics, and not trying to appear overly feminine in their appearance or behaviour.34 Balancing femininity and their military service identity can be challenging for many women, especially when this dichotomy is consistently reinforced through the actions of others. For example, women may be mocked, belittled, or harassed by fellow soldiers for being too masculine. However, many prefer this categorization to being branded too feminine.35 When it comes to femininity and military identity, women can be presented with a very challenging and narrow path upon which to walk.

DND photo by Master Corporal Andre Maillet/RP19-2018-0116-006

HMCS Ville de Québec Executive Officer Lieutenant-Commander Annick Fortin watches other NATO warships while sailing in formation inside Norway’s Trondheim Fjord during Exercise Trident Juncture, 30 October 2018.

Family Life

A difficult dichotomy for some women is that of mother and military member. The decision to have a family is often met with negativity, and it may force women to select between career advancement and family life.36,37 To avoid negativity and questions of loyalty, some women have tried to plan their pregnancies to better accommodate unit or leadership objectives. In addition, some have returned from maternity leave early to avoid missing out on career opportunities. Women have also expressed concern with respect to their supervisors or leaders, questioning their ability to go on training exercises when they are nursing their babies.38 Many women acknowledge that there is some inconvenience rendered to their colleagues when taking maternity leave, or even when nursing after returning from their leave.39 However, understanding and support reflected in CAF policies and culture would go a long way in alleviating the stress that some women feel when they choose to have a family. Families have long been valued as a critical piece in the health and well-being of service members,40 and allowing service members the flexibility to care for their families is just an extension of this principle.

Care for children is a commonly-cited concern for many women in the CAF, since they are still expected to handle the majority amount of childcare.41 This includes doctor’s appointments and caring for sick children. Although partners do share in many of the household duties, women are still mainly the ones responsible for childcare and domestic responsibilities. A military occupation is relatively unique with regard to the expectations that a military organization places upon its members. The military – along with the family – has been termed a ‘greedy’ institution, due to the 24-hour, 7 day-a-week commitment, and the expectation that a soldier is first-and-foremost a soldier.42 For many women, this expectation can be difficult to balance with the demands of family life. For example, women in the military have described situations in which they have been threatened with disciplinary action for taking time to care for a sick child.43 For some women, this struggle results in having to make a difficult choice: leaving the military early, foregoing career objectives, or sacrificing time spent with family. In each of these scenarios, the military is risking the well-being of a valued and skilled employee. Such a scenario can also extend to care of parents or other family members who may be in need of assistance. A more supportive, encouraging environment for military members who have family demands would forego the need for these ‘either/or’ decisions that compromise the well-being of valued service members.

Career Progression

Progressing in a chosen career can sometimes be challenging for women in the CAF. As discussed, one challenge centres around the need to prioritize family before work, and the potential negative impact on one’s career progression.44 Other hurdles include the lack of female mentorship, and procedures surrounding career planning and advancement.45,46 Lack of opportunity to progress in one’s career is an often-cited reason for leaving a military occupation,47 and it represents a key facet in understanding women’s experiences in the CAF.

Findings from the Waruszynski et al. (2018) study highlighted the notion that some women are promoted because of their sex, and not because of their abilities.48 Women have described situations in which they are explicitly told that they will be getting a promotion because senior leadership wants more women. For women in positions of power or elevated ranks, the reasoning that a woman may be in her role due to her sex alone can translate into difficulties establishing credibility and respect among her subordinates. This questioned respect is further complicated by the fact that many women feel the pressure as a representative of their sex. If a female leader fails to gain the respect and credibility of her subordinates, she may be blamed for misrepresenting women in the military. On the other hand, if she succeeds and is promoted, her career progression may be attributed to her sex and not her merits. Essentially, some women in the military face a ‘no-win situation,’ whereby both successes and failures are attributed to the fact that they are women. Changing such perceptions would go a long way with respect to allowing women to succeed in their military careers.

One way such perceptions might be addressed is through the development of mentor-‘mentee’ relationships. Specific to the CAF, women in the Waruszynski et al. (2018) study emphasized the desire and necessity for mentorship programs in the Canadian military, but lamented the lack of women available to take on that role. Thus, while mentorship practice tends to benefit the well-being of women in the workplace, of concern is the lack of women in senior leadership roles in the military available for mentoring.

Another concern regarding mentorship is the suitability of some women, and men, to serve as mentors. Madam Justice Marie Deschamps pointed out that many women in the higher ranks have become indoctrinated into the masculine culture, and are not well-suited to take on a mentorship role.49 Senior leadership, in general, needs to continue to work towards the cultural change the CAF has espoused. However, this may be even more important for women in senior leadership roles in order to continue the progression towards a supportive work environment for fellow women. With a lack of available and suitable mentors, women in the military may be missing out on opportunities to foster their career progression. Men serving in the military can also act as role models, mentors, and allies in helping women to take on leadership roles in the CAF.

These missed opportunities are further accentuated by the lack of female representation on career advancement committees. Suzanne Raby (2017) asserts that advancement committees are predominantly made up of white males, and their decisions are not made available for review. The voices of women and minorities is missing on these committees, and the career advancement of these groups may be impacted. Taken together, the findings show that career progression is a challenging issue for many women in the CAF.

Harassment

Perhaps one of the most serious issues facing many women in the CAF is that of gender-based harassment and sexual misconduct. Harassment has become a significant issue for the CAF, as described in the Deschamps Report (2015). With 27.3% of female Regular Force members of the CAF reporting some form of sexual harassment, this issue represents a tremendous barrier to women. The type and severity of harassment ranges from so-called “low level” harassment, to unwanted touching, to non-consensual sexual activity. For many women, this harassment can begin as early as basic training.50 The implications for enduring harassment and abuse at the hands of colleagues can be varied. Some women are forced to accept this behaviour or face rejection, while others feel they are forced to leave the military in order to escape the abuse.51,52 Harassment is a serious issue with serious consequences, and it requires serious action.

DND photo by Master Corporal Gerald Cormier/RP12-2017-0083-012

Major Chelsea Anne Braybrook, Commander of Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, and a member of the enhanced Forward Presence Battlegroup in Latvia, briefs troops on plans and strategies during the NATO certification exercise at Camp Adazi, Latvia, 24 August 2017.

The official response to allegations of sexual misconduct in the CAF was the implementation of Operation HONOUR. The purpose of Operation HONOUR is to eliminate harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour in the Canadian military.53 The designation of this program as a mission within our armed forces denotes the seriousness of the response. However, this initiative has been met with skepticism regarding its efficacy.54 Although many women highlighted the importance of the initiative in the Waruszynski et al. (2018) study, some women mentioned that Operation HONOUR creates an uncomfortable and potentially-damaging divide between men and women.55 There is a perception, particularly with the frequency of presentations relating to Operation HONOUR, that men become wary of interacting with females for fear of being accused of any wrongdoing. In some cases, women have reported feeling that the initiative is shedding an unnecessary light upon them and their lives in the military.56

All workers have a right to feel safe in the workplace. Together, the observations related to Operation HONOUR and based upon the Waruszynski et al. (2018) study underline the continued need for leadership to take on the responsibility for ensuring that all members in the military are treated with respect and dignity.

Application of Standards

With the inclusion of women in all military roles in 2001, many believed that the physical standards were lowered to allow women to pass qualification tests. However, today’s military members must pass the same standardized test (FORCE) to meet the Universality of Service principle. Standards are applied to everyone regardless of age, gender, rank, or military experience, and failure to pass can lead to discharge from the military. Despite the fact that women are required to pass all the same qualification tests as male military members, perceptions can be hard to change; many people still believe that women are given an unfair advantage. This faulty perception can lead women to feel that they must continually prove their abilities. Many have asserted that once women are able to prove themselves capable, they are typically accepted. However, the onus may well be on each woman to show she is able to carry out her duties; and with each new posting and each new role, she may be required to repeat the cycle of proving her abilities.

A similarly-challenging issue for women in the military is the pressure of being a representative of the female gender. Many military women have spoken to the challenge of feeling responsible for how all women are perceived in the military. As alluded to earlier in this article, failure on the part of one woman is thought to reflect poorly upon all women in the military. Such pressure and responsibility can lead to feelings of competitiveness and friction between female members of military units. At a time when female camaraderie and support is an important step in the way forward, a competitive, tense atmosphere between women is counterproductive to the overarching goal of creating a supportive work environment for all members of the CAF. Furthermore, the added pressure of one woman feeling she has to show that all women are capable military members can add stress and create an unrealistic expectation that is challenging to meet.

The Basic Necessities

Findings in the Waruszynski and colleagues’ (2018) study reiterated the commonly-reported issue of inattention to the basic necessities for women in the CAF. Specifically, women have repeatedly raised concerns over ill-fitting uniforms and protective gear, and a lack of appropriate washroom facilities, issues that have been raised over the past 20 years. Serving women pointed out that, for example, women are physiologically built differently than men, and poorly-fitted uniforms can impact comfort levels. Anything that can affect focus, inhibit range of motion, or reduce protective capability should be a serious concern. At a very basic level, ensuring comfort and satisfaction with uniforms signifies that the organization is concerned about the well-being of its employees. At the most extreme level, ill-fitting safety equipment puts the lives of women at risk, and can potentially jeopardize operational effectiveness.

Limited access to appropriate washroom and shower facilities also puts into question assumptions of respect and dignity for women who are not afforded the same consideration as their male counterparts when it comes to privacy and personal hygiene. In addition, there can be safety concerns when it comes to showering facilities, particularly when deployed (i.e., risk of being sexually assaulted), as chronicled in the Waruszynski et al. (2018) study. Unfortunately, a few women have expressed concern over trying to access appropriate facilities without it being viewed as receiving preferential treatment.57

DND photo by Master Corporal Halina Folfas/TN2008-0139-58

Captain Diane Baldasaro poses for a quick photo as she flies a CC-130 Hercules aircraft with the residents of Kashechewan, a remote northern Ontario community located at the edge of James Bay, who were being evacuated due to a flood threat, 28 April 2008.

The Way Forward

The way forward will require greater collective leadership, integration, and teamwork to foster a CAF culture that is both welcoming of all its members and one that promotes the value of having a diverse and inclusive military environment. Numerous studies have discussed the experiences of women in the military and have provided several options for change. It is essential that members in leadership positions continue to address the challenges experienced by women and further take the necessary actions that will generate a more positive military culture. The newly-published defence strategy, Strong, Secure, Engaged, speaks to the fact that the military is in the midst of a cultural change through the emphasis placed upon diversity, inclusiveness, and the importance of fostering a supportive and safe work environment for all CAF personnel.

Family-Friendly Environment

There is a need to consider how personnel policies are applied so that they are supportive of a strong work-life balance for all service members. This could include consideration of new forms of support, such as day-care arrangements and enhanced services offered by the CAF. Raby (2017) discussed the possibility of having flexible day-care options and the importance of having programs in place to help with postings and training schedules that are not conducive to regular 9-to-5 day-care centres. In addition, women have decried the inflexibility of their schedules which restrict their ability to attend to children’s medical appointments, or care for their sick children. Allowing for service members to take time to go to appointments and attend to sick children without fear of reprisal will encourage a family-friendly, supportive work environment. This can also extend to aging parents or other family members in need of care.

Mentorship Programs

The implementation of a formal mentorship program was a key recommendation made by both Raby (2017) and Waruszynski et al. (2018). A mentorship program can provide two important services to women in the CAF. For example, mentors can help to guide and support ‘mentees’ in their careers, and they can also act as exceptional listeners, advisors, and confidantes. It is important for women to see that others have been successful in their careers, and that women do have opportunities to forge their paths and progress in their chosen careers.

Another important recommendation made by both Raby and Waruszynski is the need to create an accurate portrayal of what life is really like in the military. Women in the military have expressed concern with respect to the way media and recruitment messages portray them and their daily lives as military personnel.58 To help clarify these portrayals, some women have suggested the use of social media, such as YouTube channels run by women showing their day-to-day routines. This increases engagement with the general population, and provides what is perhaps a more accurate glimpse into these women’s lives.

An interesting program that may provide women with an accurate glimpse into the military is the Women in Force program. This is a new initiative that is currently being evaluated for its efficacy, and is one that may offer a more unique introduction to women interested in a military career.59 The program was designed to offer interested women the opportunity to experience the military through hands-on activities, presentations from members of the CAF, and living the profession for a few days. Such new and unique ideas may help facilitate the attraction and retention of women in the CAF, and also foster connections between those currently serving and those who are new to the profession.

Safe and Supportive Environment

The implementation of Operation HONOUR demonstrates the importance of the CAF leadership’s response to resolving sexual misconduct in the Canadian military. However, the program is not without its drawbacks. Although the ultimate goal of this program is to make the CAF a safe and supportive environment for all service members, some members do not see it as effectively accomplishing this goal. As such, it is important to examine the efficacy of Operation HONOUR and to determine if any gaps continue to exist in response to eliminating sexual misconduct in the CAF.

Value in Diversity and Inclusivity

What occasionally gets lost in the political messaging is the desire to attract and retain skilled and highly capable members in the Canadian military. Presently, a large portion of the Canadian population does not consider the Canadian military as a viable career option.60 A lack of diversity and inclusivity may limit the capabilities of the military, particularly if individuals are focusing upon their careers elsewhere. The landscape of military operations is changing and requires a variety of skillsets in order to achieve mission success. The archetypal image of a warrior needs to change to meet the modern landscape of military operations.

Conclusion

To move forward, the military culture must continue to evolve to better foster diversity and inclusion in the Canadian military. By promoting a more diverse and inclusive military, the CAF will not only bolster the military workforce, but it will ultimately strengthen military capabilities and operational effectiveness. Through its defence policy, Strong, Secure, Engaged, the CAF is committed to increasing the representation of women in the Canadian military, and to ultimately, generating greater diversity and inclusivity in the Canadian military. The future of the CAF as a diverse and inclusive military institution is promising, and it will serve to further augment the diverse Canadian population that it serves, both domestically and abroad.

Notes

- Employment Equity Statistics. (August, 2018). Director Human Rights and Diversity CAF Employment Equity Database.

- Earnscliffe Strategy Group. (2017). The Recruitment and Employment of Women in the Canadian Armed Forces: Research Report. Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2017-003. Contract Number: W7714 166200/001/CY.

- B.T.Waruszynski, K.H. MacEachern,, & E. Ouellet, (2018), Women in the profession of arms: Female regular force members’ perceptions on the attraction, recruitment, employment, and retention of women in the Canadian Armed Forces (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Scientific Report DRDC-RDDC-2018-R182, 2018).

- S.M. Raby, (2017), Tiger Team Report – recruitment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces. Department of National Defence, Ottawa, 2017.

- L.K. Davis, Employment of women in the Canadian Armed Forces past and present. Department of National Defence: Director of History and Heritage (86-330). Ottawa: 1966.

- B. Dundas, A history of women in the Canadian military. (Montreal: Art Global, 2000).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Dundas.

- Davis.

- C. Gossage, Great coats and glamour boots. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2001).

- Davis.

- Dundas.

- Ibid.

- Gossage.

- Ibid.

- Director of History and Heritage. (1941). Information of the use of women who wish to apply for enrolment as full time auxiliaries in the Canadian Armed Forces. Department of National War Services Canada.

- S. Simpson, S., D. Toole, D., & C. Player, C. (1979). Women in the Canadian Forces: Past, present and future, at: <http://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/download/4760/3990>.

- Director of History and Heritage. (1979). Remarks by the Honourable Barney Danson, Minister of National Defence: The role of women in the CF (#86-330).

- R. Charlton, R. (n.d.). Women in the CF: most welcome but there are problems to sort out. (#83-231).

- Government of Canada. (1970). Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada.

- Simpson et al.

- Canadian Forces. (1969). Distribution of women by trade in the CF. Ottawa: 1969.

- Director of History and Heritage. (1979).

- Government of Canada. (1985). Prohibited grounds of discrimination. Canadian Human Rights Act, at: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/H-6/page-1.html#h-5.

- L.A. Karmas, (1984). Trial employment of Canadian Forces servicewomen in a combat service support unit. Unpublished Master’s thesis.

- National Defence. (1987). Combat related employment of women (CREW). Library and Archives Canada (#2009-00385).

- Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis. (2018). Historical personnel database derived from extracts from the Human Resources Management System, 1982 to 2018 (Director Human Resources Information Management). Ottawa, Ontario: Department of National Defence.

- Waruszynski et al.

- Raby.

- Waruszynski et al.

- Ibid.

- N. Taber, “Learning how to be a woman in the Canadian Forces/unlearning it through feminism: An autoethnography of my learning journey.” in Studies in Continuing Education, 27(3), (2005), pp. 289-301.

- J.M. Silva, “A new generation of women? How female ROTC cadets negotiate the tension between masculine military culture and traditional femininity.” in Social Forces, 87(2), (2008), pp.937-960.

- N. Taber, “‘You better not get pregnant while you’re here’: Tensions between masculinities and femininities in military communities of practice,” in International Journal of Lifelong Education, 30(3), (2011), pp. 331-348.

- Waruszynski et al.

- Ibid.

- M.E. Therrien, I. Richer, J.E. Lee, K. Watkins, & M.A. Zamorski, “Family/household characteristics and positive mental health of Canadian military members: Mediation through social support,” in Journal of Military, Veteran, and Family Health, Vol. 2, (2017), pp. 8-20.

- K. Petite, Tinker, tailor! Soldier, sailor! Mother? Making sense of the competing institutions of motherhood and the military (Unpublished Master’s thesis). (Halifax, Nova Scotia: Mount Saint Vincent University, 2008).

- M.W. Segal, (1999). “Gender and the military,” in J. S. Chafetz (Ed.) Handbook of the Sociology of Gender. (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), pp. 563-581.

- Waruszynski et al.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Raby.

- K. Michaud & I. Goldenberg, (2012). Canadian Forces exit survey – Gender analysis (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Scientific Letter Report 1150-1). (Ottawa: Defence Research and Development Canada, 2012).

- Waruszynski et al.

- M. Deschamps, (2015). External review into sexual misconduct and sexual harassment in the Canadian Armed Forces (Contract No 8404-15008/001/7G). (Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 2015).

- Waruszynski et al.

- S.L. Buydens, (2002). “The lived experience of women veterans of the Canadian Forces.” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis), at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.829.9212&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- M.E. Dichter, & G. True, (2015). “‘This is the story of why my military career ended before it should have,’: Premature separation from military service among U.S. women veterans,” in Journal of Women and Social Work, Vol. 30, (2015), pp. 187-199.

- Department of National Defence. (2017). Operation HONOUR, at: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/benefits-military/conflict-misconduct/operation-honour/about-operation-honour.html.

- A. Cotter, (2016). Sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016), at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-603-x/85-603-x2016001-eng.pdf.

- Waruszynski et al.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Raby.

- Earnscliffe Strategy Group. (2017).