Education and Training

DND photo AK02-2018-0036-030

Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre Leroux, Commander of Joint Task Force-Ukraine, visits with Canadian Armed Forces members during T-80 tank training at the International Peacekeeping and Security Centre in Lviv, Ukraine, during Operation UNIFIER, 26 October 2018.

Security Force Capability Building 2.0: Enhancing the Structure behind the Training

by Pierre Leroux

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre Leroux is an infantry officer of the Royal 22nd Regiment, who most recently commanded Operation UNIFIER, Rotation 6, in Ukraine, from September 2018 until April 2019. 12 July 2019 marks the end of his tenure as commander of 1st Battalion, the Royal 22nd Regiment.

Introduction

Security Force Capability Building (SFCB) immediately evokes hands-on and direct training to a host nation’s (HN) developing military force. When I was told I was going to command OP UNIFIER, Rotation (Roto) 6, conducting range events, and providing direct training to Ukrainians were the first things that came to mind. At that moment, I had no idea that Training Development Officers (TDOs) would end up being our most valuable assets, and how understanding and enhancing the structures behind the training would be crucial to our success. Considering what I have learned during this mission, I must admit that I was ill-prepared for this particular type of operation. Hopefully, this article will provide useful insight, not only to future OP UNIFIER rotations, but also to any other Security Force Capability Building missions. First, it is important to not only explain what we have done in our work to enhance the Security Forces of Ukraine (SFU),1 but also the reasoning behind those initiatives. I will then touch on some notable achievements towards developing enduring effects. Finally, I will conclude with some recommendations for future SFCB commanders and leaders.

Context: Identifying the Problem

The first document I read to prepare for this mission was the Roto 3 end-of-tour report that was produced about a year before our own deployment, in September 2017. Among the expected content of such a document, it described one important principle with which I identified, namely, the need to produce more enduring effects in order to have a true impact on the Security Forces of Ukraine. The reasoning was that providing direct training, as UNIFIER was mostly doing at the time, was not creating long-term change, especially considering the very high attrition rates of the SFU (estimated to be more than 30 percent). We were doing great things and passing on our valued expertise and knowledge. However, we were only influencing a small fraction of the well-over 200,000 soldiers in the SFU. The report concluded with the necessity to look beyond direct training towards creating institutional and systemic enduring effects. From that document, a seed was planted.

Under the guidance of Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC), and through the great initiatives of the next two rotations, a shift occurred from supporting collective training in Combat Training Center Yavoriv (CTC-Y) – an equivalent to some extent to our own Canadian Manoeuvre Training Centre Wainwright - to expanding our footprint to individual training centres across Ukraine. At the time of transfer of command authority between Roto 5 and Roto 6 in September 2018, about a third of the 200 members of Joint Task Force Ukraine (JTF-U) were positioned outside of CTC-Y across Ukraine supporting individual training in various training centres. These changes, as well as the addition of two Training Development Officers, played a crucial role in our understanding of Ukrainian training methods, and more importantly, the precise problems at the heart of the issue.

However, at transfer of command authority, it was not yet clear to the leadership and planning team how to produce actual enduring effects. During a collaborative mission analysis session in the pre-deployment training period, we agreed upon the general intent and importance to strive to produce durable changes that would enable the self-sustainment and autonomy of the Security Forces Ukraine. The ‘what’ was clear, but not the ‘how.’ During the relief in place period, we were able to better understand the impacts of the recent use of a Systems Approach to Training (SAT) in three domains: Military Police (MP), Engineers, and the National Guard of Ukraine (NGU). Although we had touched upon the subject during the tactical reconnaissance visit and follow-on discussions, this initiative was still in its very early stages. The MPs were the most advanced, while the Engineers and the NGU started using these concepts in the weeks leading to the transfer of command authority to produce general occupational specifications broken down into development periods. As these particular initiatives affected the structure of specific trades and NGU NCOs in general, it became clear that a Systems Approach to Training could make a difference to the overall training systems.

Evaluation: Finding the Right Path to Enduring Effects

In the first month of our rotation, we took the time to evaluate all aspects of current initiatives, with a view to provide clear direction towards creating enduring effects. Our disposition throughout various types of training centres, and the expertise of the TDOs were key to highlighting an important fundamental aspect of the Ukrainian training system. It is based upon the instructor, and not upon the learner’s results. In most cases, there are no formal performance standards, with courses being process-based, rather than result-based. Making this connection was an important step to our understanding of this complex problem and how we were going to solve it. No precise performance objectives with respect to individual training means the quality of the instruction is uneven from one class to another, and consequently, the end result is also variable. Furthermore, it raised the fundamental question: what precise end-state are the different individual training courses striving to achieve? There was no clear answer. Our first 30-day analysis showed us that this problem was spread across the entire Security Forces Ukraine. We had put our finger on the problem, and a Systems Approach to Training appeared to be a promising solution.

For a start, let me explain SAT as it was demonstrated to us by our experts, the Training Development Officers. Considering training serves the purpose of preparing military personnel to perform their operational tasks to the required degree of proficiency, SAT is a requirements-driven approach to instructional systems design. By placing the focus upon the intended results of instruction, SAT ensures training meets the performance requirements of corresponding job tasks. In essence, it is a method which drives training toward a specific and precise end state. By doing so, it provides relevance to training plans, and it fosters efficiency. SAT is adaptable to specific courses, such as the MP investigator course, or defining a completely new trade, for example, medical technicians. It can be used to solve wider problems, such as generating a new professional NCO Corps, to more specific problems, such as ensuring the proficiency and quality of snipers.

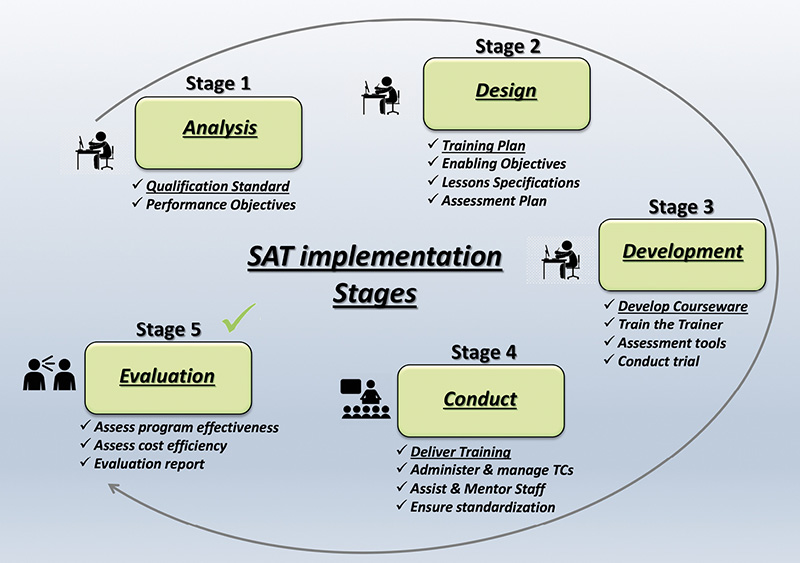

To achieve the required training outcomes, SAT relies upon a five-phase process. The Analysis phase captures these outcomes in the form of Performance Objectives (POs). The Design phase describes a training program enabling learners to achieve these objectives. Instructional material is produced during the Development phase, while the Implementation phase consists of delivering the instruction. The Evaluation phase, which occurs throughout the SAT process, assesses the effectiveness and efficiency of the training program, and recommends improvements, if and as required.

Thus, a Systems Approach to Training is a great method to create enduring effects, since it produces foundational documents for individual training courses, such as Qualification Standards, Training Plans, and certain courseware. These products will ‘endure’ beyond the inevitable departure of Canadians, while building a solid foundational structure to the SFU’s training system.

Author

Figure 1: A conceptual illustration of SAT as a solution toward a clear end state.

Analysis: Conceiving the ‘How’

Having completed our first 30-day evaluation, we were ready to provide more detailed direction and guidance to the Task Force. Prior to our deployment, we issued an operation order, detailing the intent and aim to produce enduring effects. The ‘how’ we were going to proceed now needed more clarity by virtue of a fragmentary order. To capture the essence of our analysis, we will use the ends-ways-means format:

- Ends: Produce enduring effects on the training system to enhance the SFU capabilities and professionalization.

- Ways: Improve the structures behind the training system by implementation of a SAT where possible.

- Means:

- Doctrinal knowledge of Canadian Forces IT&E Systems (CFITES) to understanding SAT

- TDOs as subject matter experts

- Provide training to task force and Security Forces Ukraine (Qualification Standards Plans manager course)

- Support the SFU to lead writing boards to formalize Qualification Standards (analysis – Stage 1) and Training Plans (design – Stage 2)

- Provide guidance on other possible structural changes: enduring effects scale

- Stand-up a new sub-unit focused upon Systems Approach to Training development

- Acquire the ‘buy-in’ from top SFU officials

Through the analysis, it also became evident enabling operations were required to facilitate the implementation of SAT. First, in the context of the SFU mindset and the Soviet legacy, acquiring ‘buy-in’ from higher echelons was crucial to this implementation. Informing and convincing SFU top echelons became an essential step in formalizing the structural changes we were proposing. To ensure coherence and unity of effort, we also needed to get our multinational partners on board. Acquiring the support of NATO’s Defense Education Enhancement Program proved very beneficial, as that support gave us added credibility. Finally, our involvement in collective training (CT) at CTC-Y remained important to understand the overall situation. In essence, CT is the final step of any Force Generation (FG) model, and in a way, it is figuratively ‘where the rubber meets the road.’ We needed to keep a strong foothold in collective training to evaluate the results of our individual training efforts, and to create a feedback loop. We also identified a tremendous amount of opportunities to enhance the structures supporting collective training. From updating doctrine, to formalizing range control procedures, to demonstrating how to organize and plan a live fire exercise, we had the opportunity to work on the structures behind the training, versus the training itself. This became an important part of our concept, as a significant portion of our task force was still involved in collective training, and it kept them involved. From the corporals to the captains and majors, everyone had opportunities to produce enduring effects.

Author

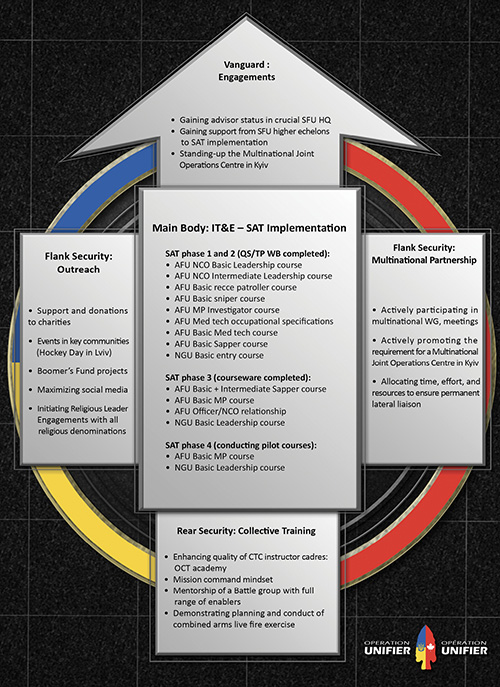

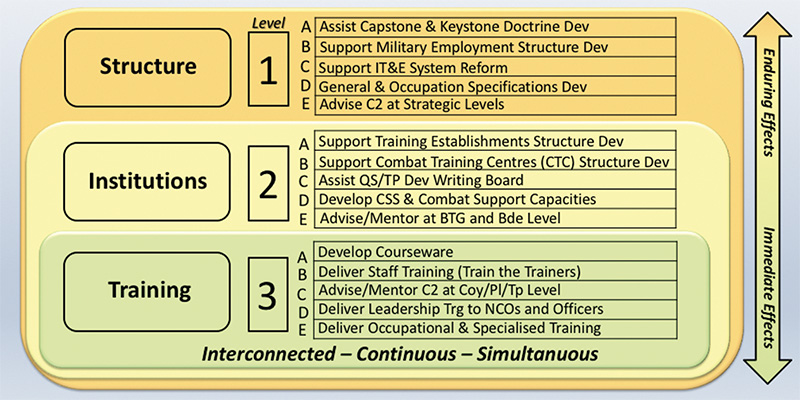

Figure 3: Enduring Effects Scale. The initial intent was to use it as a sequential, progress-based matrix. However it quickly became clear that one training group, and even one specific project could require efforts at different levels, and that progress was not in fact linear in this way. The Scale now serves as a way to identify the work that is being done, and provides visual representation of possible next steps. Each step and level can be interconnected, continuous, and simultaneous.

Conceptually, here is how the scheme of manoeuvre was broken down:

- Shaping operation: Engaging with Security Forces of Ukraine leadership and headquarters to acquire their ‘buy-in’ and support for SAT and supporting initiatives

- Decisive operation: Enhancing the Individual Training and Education (IT&E) system by implementing SAT to ensure the quality of training

- Supporting operations:

- Enhancing the collective training at CTC-Yavoriv by mentoring a Battle Group instructor cadre to foster quality training and augment our situational awareness with respect to the efficiency of individual training

- Coordinating with our multinational partners to promote synergies and to ensure coherence

- Engaging the local population via outreach programs to maintain their support

Results: Measuring our Progress

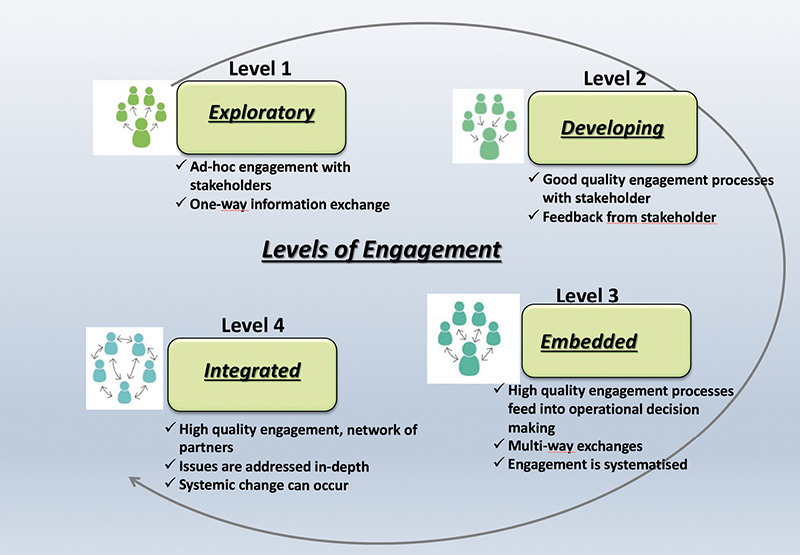

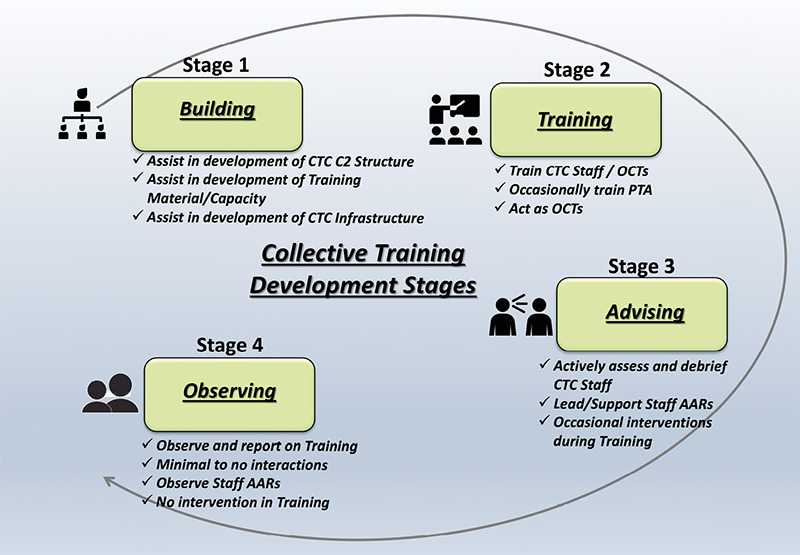

To situate ourselves and follow our progress, we decided to limit our tracking system to three priorities: IT&E, engagements, and collective training. With respect to these three themes, we linked specific doctrine with the Security Force Capability Building manual (which is still in draft):

- IT&E: Canadian Forces IT&E Systems

- Engagements: Stakeholder Engagement Guide

- Collective Training: Security Force Capability Building (CAN), and Allied Joint Doctrine for Security Force Assistance (NATO)

The intent was to formalize a tracking model specific to these subjects which would describe each step from the start of an initiative to disengagement, once the conditions are in place for the Security Forces Ukraine to make a full takeover. It is first and foremost a quantitative tracking system, as it does not measure the quality of the progress.

The most obvious observation of our tracking system through our rotation was that we started our rotation with less than ten IT&E initiatives, and ended the tour with 37 of them (23 at mid-tour). Each of these initiatives is a Systems Approach to Training cycle in itself, all of which are at various stages. Although slow to start, SAT really caught on over the months, particularly after it was formally supported at the higher levels of the Armed Forces Ukraine, and when we expanded our support to the National Guard Ukraine. Considering each of these cycles requires a writing board (WB) for the analysis and design phases, and then significant work over weeks and months to develop the proper courseware and to conduct pilot courses, each full cycle can take between 18 and 24 months. Each of them is a significant endeavour. This is why it is important to set the conditions for the SFU to take the lead from the start, supported by our expertise, as JTF-U resources are too scarce to support every cycle. Time spent on training and preparing SFU personnel for these writing boards and courseware development is of the utmost importance to make SAT sustainable.

DND/Joint Task Force Ukraine photo AK02-2018-0061-315

Lieutenant-General Jean-Marc Lanthier, Commander of the Canadian Army, visits with members of Operation UNIFIER conducting battalion training with the 94th Marine Infantry Battalion at the International Peacekeeping and Security Centre near Starychi, Ukraine, 5 December 2018.

A positive example of this observation is the NGU Basic training writing board held during October and November of 2018, to which 15 NCOs from across Ukraine were assigned, and they took complete ownership of the process. We supported this writing board with one Canadian TDO, one NCO and one translator, along with a Canadian major supervising part-time. The writing board produced qualification standards and training plans completely adapted to the needs of the NGU. The easy method would have been to duplicate our own CAF documents, but that would not have been adapted to the true needs of the NGU, nor would it have done anything to build their internal capacity and expertise to conduct such writing boards themselves in the future.

On the other hand, we have also had mitigated success where on occasion the Armed Forces Ukraine has not taken ownership and waited for Canadians to do the work. This occurred with respect to the Basic Sapper courseware development, where the AFU did not take into account the work required to generate over a hundred lesson plans. This resulted in the pilot course being postponed by five months. True ‘buy-in’ is required, and shaping operations are as important to set the right conditions for real progress and success.

As we were gaining knowledge and situational awareness, we also observed an increase in the number of organizations we were engaging, and the quality of these engagements. It became crucial to approach and track engagements in an organized and logical manner, as they are key to our ability to work at the institutional level. Thus, the Engagements Progression Conceptual Framework was used to ensure we remained focussed upon our objectives. In order to obtain ‘buy-in’ from different levels across different organizations, we strived to be recognized as advisors and partners. We also dedicated significant efforts to convince the SFU leadership. This proved a difficult challenge, particularly with the AFU, but it was an absolute necessity. In the last month of the tour, after much relationship-building, the advisors at the General Staff and the Land Force Headquarters2 were providing advice and working closely with their counterparts (Level 2 – Developing), while the advisor to the NGU was totally integrated within the organization (Level 4 – Integrated). It required two-thirds of the tour to get to this point, which makes the case for longer tours for specific positions, such as advisors. Each rotation of personnel causes a degradation of relationships, as trust and knowledge must be re-built, and over time, this becomes frustrating for host nation staff. While NGU stands apart as a Level 4 engagement, many stalled at Levels 1 and 2 during the bulk of our rotation.

Finally, we also tracked our progress supporting collective training by focusing upon building the structure supporting CTC-Y, and enhancing the capacities of the instructor/Observer Controller Trainer (OCT) cadre, in accordance with the recently-approved training standards. We continued to move away from direct training and towards an observer/mentor role for the observer controller trainers, providing them advice and concentrating upon building their competencies. Between training unit rotations, we provided direct training to the OCT staff, with a view to enhance their expertise and knowledge of the newly-implemented standards. We also focused upon the range safety rules and regulations to conduct live ranges, as they were lacking in that specific field. Overall, it was assessed that we were working at Stage 3 (advising) of the Collective Training Progression Conceptual Framework, with occasional efforts directed at Stages 2 (training) and 4 (observing), depending upon the group with whom we were working.

What became crucial was not the end-product of a particular writing board, or the quality of a platoon attack at CTC-Y, but how well we were providing the SFU with tools to becoming more autonomous. Each of these efforts helped to build the structures supporting training, with a view to produce effects that would one day put us out of a job; eventually building an autonomous system that will train professional SFU personnel. By creating ways to track these different efforts, we were able to provide focus and to ensure the ‘yard stick moved to the right,’ little by little.

DND/Joint Task Force Ukraine photo AK51-2017-013-001

A Joint Task Force-Ukraine small team training instructor demonstrates magazine loading technique to Ukrainian soldiers during Operation UNIFIER at the International Peacekeeping and Security Centre in Starychi, Ukraine, 15 February 2017.

The Way Forward: Deductions and Opportunities

Considering what we have come to understand during our rotation, what follows are some deductions which could prove useful for force generation and employment purposes of future OP UNIFIER rotations.

Force Generation:

- Doctrinal foundation is important: read and familiarize everyone with Canadian and NATO doctrine-related documents, particularly CFITES;

- Training: Qualification Standards/Training Plan (QS/TP) courses for everyone implicated in/with IT&E;

- Understanding the structure behind the training: A visit to/from Canadian Army Doctrine and Training Centre Headquarters with briefings on various subjects (standard cells, how to manage SAT cycle at higher level, Canadian Manoeuvre Training Centre organization, etc.);

- Participate in real QS/TP writing boards. Canadian Army training centres are always looking for help from the field force to conduct training development;

- Ensure TDOs are detached to the task force from the start of Theatre Mission Specific Training (TMST);

- As training is only one part of building capabilities, project management experience and mindset is a real asset to ensure all aspects are taken into account (comprehensive mindset);

- Security Force Capability Building is largely based upon personal relationships. Selection of the right personnel for the right position is important, particularly for the advisors that will engage multinational partners or host nation headquarters;

- Set an environment where initiative is encouraged to find other ways to achieve enduring effects within the Commander’s intent. SAT is by no means the only method to achieve this.

Force Employment:

- Ideally, every training group should have a TDO. At a minimum, there should be three to match the geographical disposition hubs in the OP UNIFIER Joint Operations Area;

- Every SAT cycle needs to be led by SFU, supported by OP UNIFIER resources. This will set the conditions for long term success;

- While important, the real value of a writing board is not the direct results in setting Qualification Standards. Rather, it lies in building the capacity of the SFU to plan, organize and lead their own WBs and implement to rest of the SAT cycle;

- Build TDO capacity within the SFU, as this is a key element to their autonomy and the long term sustainability of their training system;

- Once the performance standards are set (though SAT), keep in mind the standards need to be observed. The next step is to build standard cells;

- SAT is not the only path to enduring effects. There are many other ways to improve the structures behind the training, like demonstrating how to plan and organize collective training events or safe combined arms live fire exercises. The important thing to keep in mind is to enhance the structures supporting training;

- Establishing relationships are very important in Security Force Capability Building. Time and resources spent on engagements is like time on recce for a raid: invaluable.

DND/Joint Task Force Ukraine photo AK02-2018-0016-052

Members of Operation UNIFIER participate in foreign weapon familiarization at the International Peacekeeping and Security Centre, 4 October 2018.

Conclusion

It is widely understood that the aim of Security Force Capability Building operations is to produce effects that will lead to the self-sustainment of a host nation. What is less understood is how to accomplish this. Hopefully, this discussion has demonstrated that a Systems Approach to Training is an excellent method to build foundational structures supporting the development of capabilities. It is a way to enhance the system supporting training that will lead to efficient, relevant, and competent security forces. It is not, however, the only mechanism to do so and it cannot be successful in isolation. There are many other ways to produce enduring effects by improving the structures supporting training. Everyone can play a role, from the soldiers on the ground mentoring a standard cell, to captains and majors demonstrating how a Battle Group command post is organized, and transforming it into doctrine. In the future, other higher level institutional opportunities should be considered to produce even more structural improvements: career management, long term business planning and doctrine writing, along with other opportunities.

CAF operators often take training - and the system behind it – for granted; career courses, pre-deployment training, annual refreshers are expected steps that must be completed. In Canada, we have the luxury of a ‘well-oiled machine’ delivering relevant training mechanisms that produce professional and proficient soldiers. In most countries where we are or will be conducting Security Force Capability Building operations, this system does not exist. To enhance such a structure, we need to understand our own, keeping in mind it will need to be adapted to the realities and the caveats of host nation security forces. That is why the recurring mantra throughout our tour was that OP UNIFIER has moved away from training, and is now focused upon enhancing the structures supporting training.

Notes

- The Security Forces of Ukraine describes both the National Guard of Ukraine (NGU) and the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU). These are two distinct organisations. The NGU falls under the Ministry of Interior, and the AFU is under the Minister of Defence. Op UNIFIER worked exclusively with the AFU until May 2018, when a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the CAF and the NGU.

- General Staff of the Armed Force of Ukraine is the headquarters and management body of the entire force. Land Forces HQ is equivalent to the Canadian Army Headquarters in Canada.