Force Structure

AB Forces News Collection/Alamy Stock Photo/MJCBE4

A Canadian Army Reservist holding a hilltop position during Exercise Cougar Rage at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington State, 28 April 2018.

The Canadian Army Needs a Paradigm Shift

by Wolfgang W. Riedel

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Colonel (ret’d) Wolfgang W. Riedel, OMM, CD, QC has served for forty-four years in the ranks and as an artillery, infantry and legal officer in the Regular Force and the Reserve Force. As Deputy Judge Advocate General – Reserves he was Canada’s Senior Reserve Force Legal Officer and was a member of the Chief of Reserves and Cadets Council.

“Our defence policy is predicated on the kind of asymmetric warfare we have faced since the end of the Cold War and it really ignores the looming strategic threats that Russia, China and maybe some others pose as well.

~ Richard Cohen1

Introduction

“Paradigm Shift – a radical change in personal beliefs, complex systems or organizations, replacing the former way of thinking or organizing with a radically different way of thinking or organizing.”2

Is the Canadian Army ready for the next conflict? Does it project a credible deterrence? This article argues that the answer is, clearly, no. As a consequence, Canada must re-assess what the Canadian Army’s structure ought to be, and, in particular, critically examine the role and organization of the Army’s Primary Reserve component (ARes).

Kremlin Pool/Alamy Stock Photo/PKGBE3

Chinese forces on parade during a review of the troops near Chita in Eastern Siberia, Russia, while deployed on the massive Vostok-2018 multi-national war games at the Telemba training grounds, 13 September 2018.

The United States Has Recognized the Threat and Is Doing Something about It

The most recent US National Defence Strategy (NDS), issued in January of 2018,3 recognizes that the US is “…emerging from a period of strategic atrophy, aware that our competitive military advantage has been eroding.” It identifies China as a “strategic competitor using predatory economics to intimidate its neighbors while militarizing features in the South China Sea,” and states: “Russia has violated the borders of nearby nations and pursues veto power over the economic, diplomatic, and security decisions of its neighbors.”4

In response to this threat, the Department of Defense (DoD), in its progress report of 26 September 2018,5 stressed the adoption of three lines of effort: Lethality—Build a more lethal force; Alliances—Strengthen alliances and attract new partners; and Reform—Reform the Department for greater performance and affordability.6

Congress’s Commission for the independent review of the NDS (NDSC)7 found, on 13 November 2018,8 that the “…security and well-being of the United States are at greater risk than at any time in decades. America’s military superiority ... has eroded to a dangerous degree ... (it) might struggle to win, or perhaps lose, a war against China or Russia. The United States would be particularly at risk of being overwhelmed should its military be forced to fight on two or more fronts simultaneously.”9

According to RAND,10 “…the US keeps losing, hard, in simulated wars with Russia and China” notwithstanding that the US has a 2019 defense budget of US$716 billion11 against China’s US$228 billion, and Russia’s US$66.3 billion in 2017.12 The problem is that the current US Full Spectrum Operations strategy is vulnerable to its adversaries’ Hybrid War and Anti-Access Denial strategies. In response, the US is developing new strategies under the rubric of Multi-Domain Operations.13

Kremlin Pool/Alamy Stock Photo/F54F4R

A military parade in Red Square, Moscow, celebrating the annual anniversary of victory over Germany in the Second World War, the Great Patriotic War.

Canada Has Recognized the Threat but Has Done Little to Respond to It

Canada’s current defence policy—Strong, Secure, Engaged (SSE), issued in 201714—concedes: “The re-emergence of major power competition has reminded Canadian Army nada and its allies of the importance of deterrence. ... A credible military deterrence serves as a diplomatic tool to prevent conflict and should be accompanied by dialogue. NATO allies ... have been re-examining how to deter a wide spectrum of challenges to the international order by maintaining advanced conventional military capabilities that could be used in the event of a conflict with a “near-peer.””15 (Emphasis added).

Canada, however, has done little since 2017 to confront the situation. It neither maintains credible “advanced conventional military capabilities,” nor is it a “near-peer” to Russia or China.

While the SSE requires the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) to be prepared to provide, simultaneously, several small sustained and time-limited deployments, there are no requirements to provide any one contingent larger than 1,500 personnel; basically a single battle group.

Is that enough? The answer has to be, “no.” “The gold standard of deterrence and assurance is a defensive posture that confronts the adversary with the prospect of operational failure as the likely consequence of aggression.”16 “At the end of the day, 450 Canadian troops and their assorted brothers-in-arms in Latvia are not going to deter Vladimir Putin’s newly-equipped armoured divisions and missiles unless they are backed up by substantial and immediately available combat forces. Canada’s ambition of ‘two sustained deployments of 500-1500 personnel’ and ‘one time-limited deployment of 500-1500 personnel’ will probably not impress Mr. Putin.”17 (Emphasis added). According to RAND, NATO needs at least seven brigades—three of them heavy—to keep Russia from overrunning the Baltic states in sixty hours.18

DND photo RP16-2018-0059-114 by Corporal Desiree T. Bourdon

Canadian Armed Forces artillery soldiers on exercise in Latvia, June 2018.

The Canadian Army’s transformation to light and medium-weight forces19 has made it an army with few teeth. The force has numerous, critical, capability gaps,20 the most significant of which is the absence of heavy-weight armoured formations.21 In the NATO and rejuvenated Russia22 context, our commitment is, at best, a trip wire—but a trip wire with nothing behind it is merely cannon fodder.

The Current Canadian Army ‘in a Nutshell’

What then is the state of the Canadian Army?

There are currently 21,600 full-time soldiers in the Canadian Army’s Regular Force component (Army Regular Force), and approximately 19,000 part-time soldiers in the Army Primary Reserve.23

The bulk of Army Regular Force personnel are found within three Combat Mechanized Brigade Groups (CMBGs). The balance is employed in a nascent Combat Support Brigade (CCSB), a deployable divisional headquarters, and various other headquarters, schools, and tasks. Its manoeuvre elements consist of six LAV3/6.0 equipped infantry battalions, three light infantry battalions, two reconnaissance regiments, and one tank-equipped armoured regiment. Separate from the Canadian Army itself is one ‘battalion plus-sized’ special operations force.

While the light-to- medium-weight Army Regular Force component of the CAF meets some of the limited objectives of the SSE, it cannot be called a credible deterrent to either Russia or China. Does the Army Primary Reserve component add any lethality or credibility?

DND photo LE2015-0056-21 by Master Corporal Mélanie Ferguson

A company of the Immediate Response Unit (West) leaves Prince Albert in a convoy of LAV 6.0s, travelling to a fire-affected zone of Saskatchewan during Operation Lentus 15-02, 13 July 2015.

The Canadian Army Reserve Is Neither a Lethal nor Credible Force

The majority of the Army Primary Reserve consists of 138 units in ten brigade groups. A fluctuating, but significant minority is employed full-time on a variety of primarily administrative, call-out positions throughout the CAF.

According to a recent Auditor General’s Report, the current Army Primary Reserve lacks guidance on preparing for major overseas missions; is undermanned; is underfunded for even the limited objectives that are currently assigned to it; and is under-trained.24 Not mentioned in the report, but critical to any consideration of the Army Primary Reserve as either a deterrent or a fighting force, is that it is a non-deployable, administrative entity with establishments at a small fraction of their Army Regular Force counterparts. It is totally unequipped to go into combat, having merely limited numbers of personal weapons and a smattering of administrative and training equipment.

Library and Archives Canada/PA-111565/Lieutenant Donald I. Grant/DND

Major David Currie (third from left with pistol drawn), a reservist of the South Alberta Regiment, accepting the surrender of German troops at St. Lambert-sur-Dives, France, 19 August 1944. Awarded the Victoria Cross for his leadership during the attack on this village, this is often cited as the closest we are likely to get to a photograph of a soldier actually winning the Victoria Cross.

How Did We Get Here?

Historically, Canada was dependent upon a part-time citizen army made up of volunteers, and a very small full-time force whose purpose was to train the part-time force. This structure enabled Canada’s contributions in the two world wars where the country mobilized—at times augmented by conscription—upon the base of its citizen army.25 During the Second World War, Canada had the fourth-largest allied active military, consisting of more than 1.1 million personnel.

After the Second World War, the Canadian Army part-time force was authorized at some 180,000 personnel in six divisions, four armoured brigades, and attachments. The Canadian Army full-time force was authorized at 27,000 personnel, including an airborne, brigade-sized Mobile Striking Force (MSF). By 1949, both components were under strength.

In 1950, Canada raised a brigade for Korea, largely recruited from Second World War veterans,26 and in 1951, committed to contributing new forces to NATO to oppose the Soviet threat. By 1954, the Canadian Army’s part-timers had dwindled to 46,506 members, while the full-time component had grown to 49,978 personnel, including a division with four combat mechanized brigade groups, one of which was deployed to Europe. The then-Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, articulated the proviso that if Canadian soldiers were to fight there, they would have to be there at the start of hostilities. Shipping a large force from Canada to Europe was not an available option.27

Canadian National Defence Image Library/CC-9582

Canadian militia soldiers from the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa manning their machine gun while serving in the Korean War.

In 1963, the Regular Force —as it was now known—reached its peak of 120,871 personnel, (without any increase in combat mechanized brigade groups), while Primary Reserve membership numbers and equipment declined. Thereafter, numbers for both components slid as salaries climbed, budgets became tighter, and senior military leadership unsuccessfully wrestled with an escalating bloat in headquarters staffing. Notwithstanding funding issues, the 1950s/1960s mentality of a large, costly Regular Force—as forces-in-being—with a Primary Reserve—as individual augmentees—continued unchallenged. These consequential compromises have resulted in today’s dysfunctional 100-person Army Primary Reserve battalions, commanded by lieutenant- colonels that have neither the trained personnel, nor the equipment to make it possible to activate them.

Lessons from Afghanistan

Canadian operations in Afghanistan have been both a boon and a detriment for the Army Primary Reserve. Canadian contingents there were made up of 15-to-25% reservists. In total, 4,642 reservists deployed, suffering 16 fatalities and 75 wounded.28 While on one hand, this provided much needed combat experience to bring back to Army Primary Reserve units, it also reinforced the concept that the Army Primary Reserve solely fulfills an individual volunteer augmentee role, rather than a capability to compulsorily deploy formed units or sub-units.

Lieutenant-General Andrew Leslie, a former Canadian Army commander, said: “The Army could not have done what it did in Afghanistan without the Reserve. We would have crashed and burned. The country owes them a huge debt of gratitude.”29 Assuming that this is not merely hyperbole, it gives rise to the sobering conclusion that the entire Army Regular Force establishment, including its three brigade groups, could not maintain, for an extended period of time, a single battle group-sized task force in an operational theatre without undergoing severe stress. While much of this may well have been due to the short personnel tours (six months), the extensive pre-deployment training cycle, the necessity for providing individuals with mid-tour leave and post-deployment reconstitution cycles,30 Canadians must wonder if our financial investment in the Army Regular Force and Army Primary Reserve establishments, as currently configured and administered, is value for money.

A second and equally- significant lesson is that reservists, properly trained, equipped and led, can carry out combat operations.

A Transformation of the Canadian Army Primary Reserve Can Help Us Meet the Threat

How—in the words of the US DoD lines of effort—can Canada reform the CAF for greater performance and affordability, build a more lethal force, and strengthen our alliances? Currently half of Canada’s defence budget goes to personnel costs.31 Our headquarters continue to add General and Flag Officers at an alarming rate, creating ever- expanding bureaucracies at the expense of war-fighting elements. Canada’s military and associated civil servant salaries are among the highest paid in NATO, while the percentage of it’s expenditures on equipment are a fraction of that of its allies.32 Canada must change that ratio, and one of the more obvious choices for change is through the use of the Army Primary Reserve. Year-to-year, part-time reservists cost a fraction of their Regular Force counterparts.

Fundamentally, a military reserve force exists to allow a country to reduce its defence expenditures in peacetime by keeping on stand-by those forces needed only in emergencies up to and including war.33 Reserve forces should exist, not only as individuals who augment the full-time units, but also as organized, equipped, and deployable units and formations in order to create an affordable, larger, more lethal army.34

Canada must leverage its Army Primary Reserve into credible, effective, deployable entities capable of meeting the recognized threats.

There Are Alternative Models

While there are numerous reserve force models to examine, we can limit the examination to just two: Those of the United Kingdom and the United States.

UK Model:

For nearly a century, Canada structured its armed forces upon the British system, which facilitated Canadian troops fitting into Commonwealth military formations and logistics chains. More recently, the UK deployed reservists to Iraq and Afghanistan, and is currently in the midst of an initiative to increase its reliance upon the reserves by increasing their numbers under a program called Future Reserves 2020 (FR2020), which accompanies the Army 2020 restructuring.

FR2020 recognizes that reservists will be needed for almost every future military operation. The plan includes initiatives to clarify the reserves’ purpose and role, to establish integration of reserve and regular training and utilization, as well as legislative reforms.35 Much of the program concentrates upon enticements to recruiting, pay and benefits, employee protection, employer relations, transfer enticements for retiring Regular Force personnel, and so on.

The introduction of FR2020 had much to do with removing from the full-time payroll many individuals who are not required to either hone their skills, or to be available for immediate deployment on a day-to-day basis. It was envisioned to replace them with a larger number of part-timers. The UK government concurrently instituted a reduction in Regular Force strength which led to much criticism, debate, and even resistance. A revised restructure called Army 2020 Refine has changed various initial concepts and created some uncertainties for FR2020.36

Unfortunately, projected roles are, at best, limited to short-term operations, longer- term stabilization operations, selected standing commitments, and overseas deployments aimed at specific engagements in no greater than formed sub-units. There does not seem to be a role for the provision of major units or formations for general war. This contradicts the fundamental concept of a stand-by reserve force available for major operations.

Aero Archive/Alamy Stock Photo/M7TGAF

British Army Reservists from the Royal Wessex Yeomanry, and regular soldiers from the Royal Tank Regiment, along with personnel from the Royal Air Force, work together to deliver new Land Rovers by air from a Chinook helicopter.

US Model:

The US model is more relevant to Canada because we share a continent, and thereby, many of the same challenges in projecting forces overseas. Additionally, one cannot foresee Canada taking part in any major military effort in which the United States is not the senior participant.

The key reserve force category in the US is the Ready Reserve, which includes Army Reserve (USAR) and Army National Guard (ARNG) formations, units, and individuals liable to be called to active duty in time of war or other emergency. The United States Army Reserve is directly subordinate to the federal government, while the Army National Guard is subordinate to each state, and reports to its governor for local emergencies, except when called into federal service.37

In general, Active Army, Army National Guard, and United States Army Reserve units and formations are equipped and manned to the same tables of organization and equipment (TOE) in a modular concept. The intent is that the Army can use any given brigade or unit in a ‘plug-and-play’ manner.

Under the most recent reorganization plan, the US Army has 31 manoeuvre and 75 support brigades in its Active component, 27 manoeuvre and 78 support brigades in the Army National Guard, and 59 support brigades in the United States Army Reserve.

US Army manoeuvre brigades are one of three types designated: Armored, Stryker, or Infantry Brigade Combat Teams (ABCT, SBCT, IBCT). BCTs are the US Army’s primary combined arms, close combat force, and they contain a mix of manoeuvre battalions, field artillery, intelligence, signal, engineer, chemical, biological, radioactive and nuclear (CBRN) and sustainment capabilities similar to Canadian Combat Mechanized Brigade Groups. They can deploy either independently or as part of a larger force. IBCTs are light-weight formations equipped primarily with wheeled vehicles, designed for rapid deployment and dismounted operations. SBCTs are medium-weight formations based on the Stryker group of wheeled armoured vehicles—similar to Canada’s LAVs—designed for mounted and dismounted operations with greater mobility and protection, but more difficult to deploy into a theatre of operations. ABCTs are heavy-weight formations based around M1 Abrams tanks and M2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicles, designed to provide overwhelming concentrated combat power, but difficult to deploy into theatre and then to supply once there.38

Currently, the US Active Army has ten ABCTs, seven SBCTs, and fourteen IBCTs (of which five are airborne and three are air assault), while the Army National Guard has five ABCTs, two SBCTs and twenty IBCTs.39 There are eleven divisional headquarters in the Active Army, and eight in the Army National Guard.40

Support brigades include such capabilities as tube, rocket, and air defence artillery, manoeuvre enhancement, combat aviation, sustainment, and military intelligence.

While numbers fluctuate depending upon budgets and need, it is clear that the US Army keeps a significant percentage of its manoeuvre strength within the Army National Guard, and the majority of its support elements within the Army National Guard and the United States Army Reserve.41

DVIDS photo 4806306 by Sergeant 1st Class April Davis

Oregon National Guard soldiers conducting live-fire gunnery training with infantry dismounts and M2A3 Bradley Fighting Vehicles at a Combat Training Center near Boise, Idaho, 17 April 2018.

Considerations for Restructure

In any discussion about the future of Canada’s Army Primary Reserve, we must ask the following questions:

- What purpose does the force fulfill in the national interest?

- What purpose does the force fulfill in the interest of the individual reservist?

It is essential that both questions be answered in a positive manner. If there is no national interest being fulfilled by an entity, then there is no incentive for the country to invest treasure in its existence. If there is no individual interest being fulfilled, then people will not join or will leave the force very quickly, and the country will have wasted resources on them.

Canada’s military leadership has, for more than a half-century, failed to recognize that the greatest national interest the Army Primary Reserve can fulfill is to increase the lethality of the force by providing additional deployable formations and units at an affordable cost. It has shied away from any attempts for radical, or even serious reform, leaving the Army Primary Reserve to ‘coast on remote control,’ using a model that only garners minimal value for money, and leaves many reservists unfulfilled. Instead, from-time-to-time, attempts are made to ‘fine tune’ a system that is patently broken. Initiatives such as those enumerated in WayPoint 201842 are cosmetic at best, and do nothing to correct the underlying fundamental flaws in the system.

Much of this status quo psyche is driven by risk aversion. There is a reluctance to entrust serious responsibility to the Army Primary Reserve —largely driven by its current low level of capability—coupled with a fear that any meaningful changes to the Army Primary Reserve —so as to raise competence and increase employability—would inevitably require resource reallocation from the Regular Force.

There is a critical need for radical reform. If Russia is one of Canada’s acknowledged adversaries, then logic demands that the Canadian Army be capable of fielding heavy manoeuvre and support brigades with sufficient lethality, which, in conjunction with its allies, can engage Russian forces successfully in Multi-Domain Operations. The issue of affordability and the nature of this being primarily a stand-by role make it a suitable role for the Army Primary Reserve.

DND photo IS06-2019-0033-004 by Master Corporal P.J. Létourneau

A Reservist gunner from the 10th Field Artillery Regiment applies a bearing on the sight of a 105-mm C3 Howitzer gun during Operation Palaci, 21 November 2019.

Prerequisites for a More Credible Army Reserve

The following is a list of some initiatives that are essential in order to develop a more lethal and more affordable force.

Obligation to Serve:

Reservists, like their Regular Force counterparts, voluntarily enlist in the CAF, and serve until they are released. There is a generally-held attitude/misconception that only personnel in the Regular Force can be ordered to perform various duties, while a reservist has a choice as to whether to be deployed, or even to attend training. In fact, reservists, by law, can compulsorily be: placed on active service by an order of the Governor in Council (GiC),43 can be called out to perform any duty other than training;44—including by the Minister of National Defence in an emergency;45—can be called out in aid of the civil power;46 and also ordered to attend training.47 Practically speaking, however, Canada does not do any of these things.

The legislative provisions respecting active duty, call out on service, and aid to the civil power, are generally adequate, although not beyond improvement.48 On the other hand, the existing legislation dramatically undermines training within the Army Primary Reserve in that while there is clear statutory provision for ordering a reservist to train, the consequences of disobeying such an order are virtually nonexistent.

Two provisions in the National Defence Act (NDA) require that a reservist who fails to attend ordered training has to be charged and tried before a civilian court rather than under the Code of Service Discipline (CSD)—a process which is not followed because of its impracticality and almost meaningless punishment.49 This is a fundamental and fatal flaw. The result is that the chain-of-command accepts most reservists attending unit training in a haphazard manner. Without appropriate legislation and regulations by which compulsory training can internally under the CSD, essential collective training is impossible. Battalions which may have a hundred soldiers on strength typically turn out fewer than thirty members for any given exercise. This makes it impossible to achieve and maintain effective, deployable Army Primary Reserve sub-units, units, and formations. The CAF needs to instil and enforce a habit of attendance in its reservists.

Terms of Service – Release:

Current policies allow individuals to request a voluntary release prior to the end of their period of service.50 In the Regular Force, this is usually granted on six months’ notice to those who are not on obligatory service for subsidized training, and so on. In the Primary Reserve it is usually granted immediately. Regular Force individuals who have not reached compulsory retirement age are not required—and sometimes not even encouraged—to component transfer to the Primary Reserve.

Both the Army Regular Force and Army Primary Reserve have significant turnover in personnel—with consequential unit instability—by virtue of voluntary releases. In order to reduce attrition, Primary Reserve personnel should be enrolled for fixed-term contracts and be obliged to serve out their terms. Similarly, Regular Force personnel who are enrolled for fixed-term contracts should—after an initial minimum Regular Force service period—be obliged to serve out their remaining contracts in either the Regular Force or the Primary Reserve. This would bring more experienced personnel into the Primary Reserve, and would retain an individual who would otherwise be lost to service.

A system of varying contract lengths with re-enlistment bonuses would allow individuals to initially select short terms to try out the military, and would also incentivize re-enlistment. Regular Force personnel whose fixed terms have been completed or who are on indefinite engagements should be offered component transfer bonuses, based upon fixed term commitments to the Primary Reserve.

Employer/Employee Relations:

Current Canadian job protection legislation for reservists is a mixture of inadequate federal and provincial laws that provide a bare minimum of protection for reservists deploying on operations and with respect to similar circumstances.51 There is no comprehensive overarching legislation that protects reservists for all purposes, including training, and none that provides effective representation—such as ombudsmen or legal assistance—for reservists whose employers breach the law.

In the US, federal legislation52 provides protection for reservists in most circumstances ranging from guaranteed time-off for weekend training sessions, annual training sessions, and attendance at training courses, to operational deployments, and to temporary transfers to active duty. The legislation applies equally to employers subject to state legislation as well as those to federal legislation. UK legislation to implement FR2020 also expands employee protection and adds financial incentives to employers to make hiring reservists an attractive option.

Developmental Period 1 (DP1) Training:

Like their Army Regular Force counterparts, Army Primary Reserve units should concentrate upon team and collective training. Individuals undergoing DP1 training and their staff—Army Regular Force and Army Primary Reserve—should be held against separate regional depot establishments.

Much of the undervaluation of Army Primary Reserve soldiers is based upon the fact that they are currently not trained to the same standard as their Army Regular Force counterparts. That reality has some validity, although it can be equally argued that Army Regular Force soldiers receive training in excess of what is actually essential, and that there is much wasted time during Army Regular Force training.53

A key source of Army Primary Reserve recruits are students whose available training time is limited to approximately seven weeks in the summer, and weekends during the fall/winter/spring. It would be a desirable objective to have recruits complete their DP1 training during the first fourteen months of service, which could include two summer blocks of seven weeks each, selected weekends during the winter (the equivalent of three weeks), and also through distance learning programs. This would allow fully-trained soldiers to join their units the following September in time to participate at the start of the unit’s annual training cycle.54 Unemployed reservists should have the opportunity to take the entire DP1 training in a single continuous package at a national facility.

Army Primary Reserve DP1 officer training should be designed to be spread over twenty-six months, or three summer blocks and weekends over two winters, and it should be essentially identical in content to Regular Force basic officer training.

Some accommodation may be necessary for selected specialist officers and members who have already achieved professional standing.

Career Progression:

If Army Primary Reserve units are to be effective, Army Primary Reserve officers and non-commissioned members (NCMs) will require greater training and experience. Some of this may be facilitated by fewer overall numbers of units, and an influx of transferring Regular Force members, either serving out enlistment terms, or through other component transfers. Regardless, in order to keep parity of standards between Army Primary Reserve and Army Regular Force leadership, there needs to be a review of what essential skills are required by officers and NCMs as they relate to purely military leadership and operational skills which apply to both components, and those broad defence management skills and other knowledge that relates solely to the Regular Force. Career progression courses should be restructured accordingly.

Annual Training Cycles:

Currently, Army Primary Reserve units are authorized to train for 60 ‘Class A’ days and 15 ‘Class B’ days, but are limited to a fraction of that, based upon budgetary concerns. Many units train two weekends per month and one evening per week. This is undoubtedly onerous if training is to become obligatory. Army National Guard units train 39 days annually (including one weekend per month), but as of 2019, ABCT and SBCT units will be training in four-year cycles which will include one National Training Center rotation. Training days will vary from 39 in the first year to 45 in the second year, and to 60 days in the third and fourth years.55 This direction appears reasonable.

Training programs should be centrally developed and directed to ensure a national standard, and to reduce administrative efforts by individual units.

Veterans’ Benefits:

In the wake of Afghanistan, there has been much criticism respecting the current veterans’ benefits regime. In addition, there have been calls for creating parity as to benefits for Regular Force and Primary Reserve members, such as those made by the Office of the Ombudsman.56 Despite this, there is still much that needs to be done, such as filling the gap for reservists’ insurance policies that have “war and dangerous occupations” exclusions, and providing adequate long-term disability compensation for reservists injured on duty, but who have thereby lost civilian employment that compensated them above their service salary. Primary Reserve annuities currently provide benefits based upon an “accrued days of service” basis, but do not provide any compensation for the years spent essentially on “stand-by” to serve. Such a benefit would provide an added incentive for re-enlistment.

Equipment:

In order to build a more lethal, credible, and deployable force, the Army Primary Reserve must own its own equipment upon which to train and with which to deploy. Such equipment, together with a commensurate role, would create a more lethal and credible force, and consequentially, provide a raison d’être for Army Primary Reserve personnel, raising morale and enlistment incentives, and improving retention.

It is obvious that in order to be operationally deployable, the Tables of Organization and Equipment (TOE) of Army Primary Reserve units and formations should—as with the Army National Guard—be identical to their Army Regular Force counterparts, and suitable for their assigned roles. Using the overriding premise that Army Primary Reserve units should be those that are not used on a day-to-day basis, but are those kept “in reserve” for major crises, it would appear logical that Army Primary Reserve units should be primarily medium-or-heavy manoeuvre or support units.

Army Primary Reserve formations and units must have sufficient full-time maintainers as part of their establishment to ensure that a proper level of maintenance is conducted throughout the year.

Assuming then that DND/CAF is prepared to make a radical change to build a more credible Army Primary Reserve, what could or should it look like?

DND photo LF06-2019-0014-022 by Ordinary Seaman Alexandra Proulx

A Reservist soldier of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment reaches the Command Centre during Exercise Northern Sojourn 2019, in Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, 5 March 2019.

Towards a More Credible Army Reserve Force

Based upon existing Army Primary Reserve numbers of around 20,000 members, and DND’s ideal size of 29,000 members, it should appear possible and desirable to build four-to-six Army Primary Reserve modular brigade groups and their local training depots. Creation of such formations should include the following actions:

Reallocation:

Much of the required personnel and maintenance budget would come from the existing Army Primary Reserve budget.57 There will, however, be a need for capital acquisitions or rental of major equipment and its ongoing maintenance, as well as a reallocation of resources.

Reallocation calls for a critical—even ruthless—re-evaluation of which Canadian Army organizations and individual positions are essential for day-to-day operations of the CAF—including rapid-reaction forces—and those that are only required in cases of actual major emergencies, including war. The aim is to ensure that essential full-time positions/organizations are fully staffed by primarily Army Regular Force personnel, and that stand-by positions/organizations are primarily Army Primary Reserve staffed.

For the CAF to remain affordable, it may prove necessary to reallocate a number of full-time positions to part-time positions. Financially, every full-time position reallocated equates to six part-time positions, although the math varies greatly between types of units.58

Headquarters Reduction:

DND and the CAF have dabbled in the field of transformation with the aim of reducing the size of their headquarters and to rationalize their business lines.59 There has been limited success, but sadly, the bureaucracy continues to grow. During the period from 2004 to 2010, civilian personnel in the department grew by 33%, staff at headquarters above the brigade level by 46%, and within the National Capitol Region by 38%.60 In large part, the expansion has been, and continues to be, fuelled by ever-expanding business lines within the headquarters in response to the plethora of laws, regulations, directives, and perceived needs which necessitate administration.

PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo/G68G96

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris

When Sir Arthur Harris was appointed Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in 1940, he found the Air Staff “fantastically bloated” and inefficient. He instituted an across-the-board 40% reduction in staff, which resulted in the “…essential work not only still being done, but being done with much more efficiency and speed.”61

More recently, Ford Motor Company cut 7,000 white collar jobs, 20% of its upper-level managers, reducing its organizational layers from 14 to nine, because “…to succeed in our competitive industry, and position Ford to win in a fast-changing future, we must reduce bureaucracy, empower managers, speed decision making, focus on the most valuable work and cut costs.”62

Any future transformation plan must not only address a significant across-the-board reduction of National Defence Headquarters and Canadian Armed Forces Headquarters executives, managers, and workers, but also address the overriding necessity of eliminating numerous processes that do not provide an effective contribution to the defence effort. This will require an extensive review of the legislation and regulations to which the DND/CAF is subject, and how these can be eliminated, streamlined, or automated.

Consolidation:

The current structure of Army Regular Force Combat Mechanized Brigade Groups (CMBGs) of one light and two light armoured vehicle (LAV) battalions makes little tactical sense. Using current equipment and manpower, they could and should be reformed as one brigade with three light infantry battalions assigned as a rapid reaction and northern operations force, one medium brigade with three LAV-equipped battalions for UN-oriented peacekeeping/peacemaking tasks, and one heavy brigade with one tank regiment and two-to-three LAV6.0 or heavier-equipped battalions oriented on Europe. The need to retain four regional/administrative divisional headquarters should be critically re-examined.

The current Army Primary Reserve structure of ten brigade groups and 123 units manned by a small cadre of troops has outlived its usefulness. We have had no ‘mobilization’ plan for over a half a century, and therefore, the organizational structure is an anachronism, save for its historical ties to local communities.

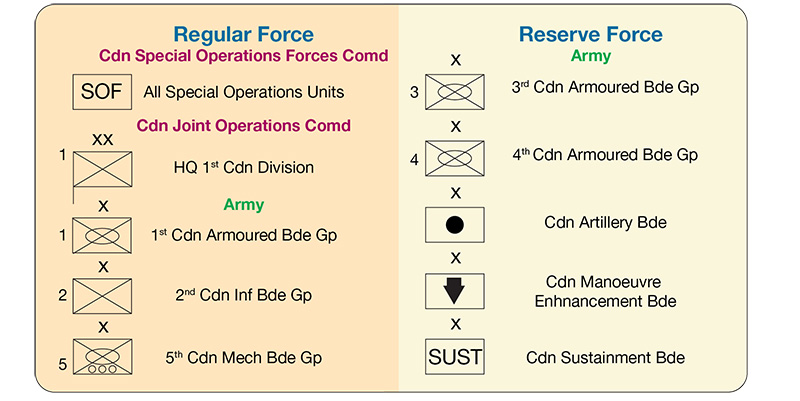

To create a credible, more lethal, deployable Army Primary Reserve, the organization must be based upon full-scale Tables of Organization and Equipment. Of the four-to-six brigades considered above, two should be heavy modular CMBGs with the same number/types of units as the Army Regular Force heavy CMBG. The remaining two-to-four additional brigades should be modular support brigades in order to provide a much greater capacity to support expeditionary forces engaged in Multi-Domain Operations. These could contain three-to-four artillery regiments (tube, rocket, air defence, possibly anti-armour), one-or-two military police battalions, a CBRN battalion, three engineer regiments, an electronic warfare regiment, and five-to-six sustainment battalions. The current Combat Support Brigade (CCSB) should be stood down and its units redistributed to Army Primary Reserve artillery and manoeuvre enhancement brigades. In total, the Army Primary Reserve would be reduced to four-to-six brigade headquarters and between twenty-eight and thirty-six fully manned and equipped battalion-sized units, depending upon the mix chosen. A sample structure for 25,000 Army Primary Reserve personnel appears at Figure 1. [To those uninitiated to army symbology, “XX” represents division strength, and “X” represents brigade strength. For the Regular Force graphics, under Army, that at Numeric “1” represents armour, armour with infantry at Numeric “2.” That at Numeric “5” represents wheeled light armoured vehicles. For the Reserve Force graphics, those brigades at Numeric “3&4” represent armour. The additional graphics represent artillery, manoeuvre enhancement, and sustainment brigades. – Ed.]

Author [Standard military symbols as per APP-6(C) NATO Joint Military Symbology]

Figure 1: Sample Regular Force/Primary Reserve breakdown of restructured major deployable formations.

For the most part, the existing footprint of armouries, support bases and training facilities should remain relevant. In many cases, ‘rebadging’ and even reclassifying existing personnel to other trades will be necessary.

Integration:

In order to establish and maintain a desirable state of readiness, Army Primary Reserve units should have an appropriate level of Army Regular Force /Army Primary Reserve personnel occupying key full-time positions, such as sufficient maintainers, stores personnel, administrators, and a few key leaders to provide command or advice to commanders. Conversely, many Army Regular Force units are currently under-resourced and/or may not need complete full-time staffing. These units could have Army Primary Reserve personnel or sub-units on their establishment.63

Business Transformation:

Even modest scale projects require a business transformation plan. A radical change of the nature proposed will clearly require an extensive and comprehensive multi-phase, multi-year transformation plan.

Some Random Closing Thoughts

The preceding has been a brief and summary review of the key issues that Canada faces. There are many more questions, including:

- Do we forward-deploy a heavy brigade group’s equipment to Europe? Forward deployment has political ramifications, however, Lieutenant-General Simonds caution still rings true. There may not, in time of emergency, be sufficient time to sea-ship equipment while a Reforger-type of fly-over force may be viable. Fly-over exercises could be annual, rotating training events for designated Army Primary Reserve units and formations.

- In order to foster greater interoperability with our closest ally, should we consider building brigades using US Tables of Organization and Equipment tactics and equipment, so that we can more easily ‘plug-and-play’ with US formations, obtain existing stocks of surplus equipment and documentation, and share their supply and maintenance systems as we once did with the UK?64

- Is there a role for the Navy Primary Reserve in purchasing/renting and manning one-or-two Roll-on /Roll-off cargo ships to facilitate overseas expeditionary operations and training activities?

- Do we need to increase our aviation resources, and in particular, do we need an attack helicopter capability and if so, is there a role for the Air Reserve in that? 65

- What role can specialized Army Regular Force and Army Primary Reserve units bring to the table to confront new systems of warfare—such as cyber, space, and hybrid—all of which are initiated from well off-shore?

- Are our defence industries and supply lines capable of ramping up so as to ensure that necessary supplies of ammunition and other vital equipment is stocked and maintained for a conflict?66

Conclusion

It is clear is that the Canadian Army is facing a significant challenge that cannot be addressed through the fine-tuning of stressed or broken organizations. Strong, Secure, Engaged identifies the developing threats that need to be faced. Against them, the current Canadian Army is neither a credible combatant nor a deterrent. A more lethal, more allied centric and more affordable force is needed.

Currently, Canada is not getting value for its defence dollars. The Regular Force is prohibitively expensive, hamstrung by its bureaucratic overhead, and incapable of expanding beyond its current size without significa0nt additional expenditures, which will, most probably, never be made available. The Army Primary Reserve is ‘broken,’ and currently incapable of providing anything beyond a small number of individual augmentees to fill gaps in the Army Regular Force. Canada’s senior leaders must utterly reject the existing Army Regular Force /Army Primary Reserve model and conduct a top-to-bottom review to determine how to build a more lethal Canadian Army, and to maximize Canada’s financial investment by leveraging its more affordable reservists.

Will there be risks? Absolutely. But there are more significant risks associated with deploying light/medium-weight Regular Force battle groups against superior, heavy-weight adversaries. There are still roles for some full-time light and medium-weight brigades and special operations forces. However, credible deterrence must include a considerable heavy-weight force which can be called upon, if needed. This entails that all soldiers—regular and reserve—must have assigned roles and be equipped and trained to deploy on Multi-Domain Operations.

DND photo CB09-2018-0068-014 by Aviator Caitlin Paterson

The Reservist Regiment Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada conducts Exercise Pegasus Strike 3 in conjunction with 32 Canadian Brigade Group, 436 Transport Squadron, and 450 Tactical Helicopter Squadron, 26 November 2018, at Canadian Forces Base Borden, Ontario.

Notes

- Murray Brewster, “Why the US could lose the next big war – and what that means for Canada,” CBC News 18 November 2018, at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/defence-policy-trump-china-russia-1.4910038

- “Paradigm Shift” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradigm_shift#Other_uses.

- The NDS is classified. For an unclassified version, see: Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America, Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, Washington, 2018, at: https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

- Ibid, p. 1.

- Department of Defense, Providing for the Common Defence – A Promise Kept to the American Taxpayer, 2018, at: https://media.defense.gov/2018/Oct/03/2002047941/-1/-1/1/PROVIDING-FOR-THe-COMMON-DEFENSE-SEPT-2018.PDF.

- Ibid, pp. 1-2.

- US Congress, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 s. 942, at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-114publ328/pdf/PLAW-114publ328.pdf.

- NDSC, Providing for the Common Defence – The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defence Strategy Commission 2018, at: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/providing-for-the-common-defense.pdf.

- Ibid, pp. v-vi.

- Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “‘US Gets Its Ass Handed To It’ In Wargames, “in Breaking Defense 7 March 2019, at: https://breakingdefense.com/2019/03/us-gets-its-ass-handed-to-it-in-wargames-heres-a-24-billion-fix/.

- “2019 Defense Budget Signed by Trump,” in Defense Benefits 2018, at: https://militarybenefits.info/2019-defense-budget/.

- “Global Military Spending remains high at $1.7 trillion,” in Stockholm International Peace Institute, 2 May 2018, at: https://www.sipri.org/media/Primary Reserves-release/2018/global-military-spending-remains-high-17-trillion. It can be argued that both receive more bang for their defence dollars. See, i.e., Tobin Harshaw, “China Outspends the US on Defence? Here’s the Math,” in Bloomberg, 25 May 2018, at: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2018-05-25/china-outspends-the-u-s-on-the-military-here-s-the-math

- Major Kristian Udesen, “The Multi-Domain Battle: Implications for the Canadian Army,” Canadian Forces College, 2018, at: https://www.cfc.forces.gc.ca/259/290/405/286/udesen.pdf. See also: TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1 US Army Multi-Domain Operations 2028, at: https://www.tradoc.army.mil/Portals/14/Documents/MDO/TP525-3-1_30Nov2018.pdf

- National Defence, Strong, Secure, and Engaged Canada’s Defence Policy, Ottawa, 2017, at: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/mdn-dnd/D2-386-2017-eng.pdf and http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/mdn-dnd/D2-386-2017-fra.pdf.

- Ibid, p. 50.

- David Ochmanek et al, “U.S. Military Capabilities and Forces for a Dangerous World,” RAND Corp 2017, p. 45, at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1782-1.html.

- Richard Cohen, “Strong, Secure and Engaged – More of the Same?” Mac-Donald-Laurier Institute,12 June 2017, at: https://www.macdonaldlaurier.ca/strong-secure-and-engaged-more-of-the-same-richard-cohen-for-inside-policy/.

- David Shlapak et al., “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank,” RAND Corp 2016, at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html. See also: https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT467.html.

- Canadian Army Land Warfare Centre, in WayPoint 2018, p. 29 at: http://www.army.forces.gc.ca/assets/ARMY_Internet/docs/en/waypoint-2018.pdf. WayPoint 2018 is a status report of the Canadian Army’s transformation under Land Operations 2021, at: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2009/forces/D2-188-2007E.pdf, which itself is being replaced by Close Engagement: Land Power in an Age of Uncertainty, Canadian Army Land Warfare Centre, which is in draft form.

- See, for example, Major Cole Petersen, “Organizing Canada’s Infantry,” in Canadian Army Journal, 16.2 201, pp. 54, at: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/mdn-dnd/D12-11-16-2-eng.pdf.

- See, for example, Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Halton, “The Re-transformation of the Armoured Corps,” in Canadian Army Journal, 17.3 2017, p. 65, at: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/mdn-dnd/D12-11-17-3-eng.pdf.

- Keir Giles, “Assessing Russia’s Reorganized and Rearmed Military,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2017, at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2017/05/03/assessing-russia-s-reorganized-and-rearmed-military-pub-69853.

- Canadian Armed Forces Website, at: http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/about-org-structure/canadian-army.page and http://www.army-armee.forces.gc.ca/en/about-army/organization.page. Figure does not include a further 5,000 personnel of the Canadian Rangers.

- Auditor General of Canada, Canadian Army Reserve—National Defence, Report 5, Spring 2016, at: http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201602_05_e_41249.html

- Canadian Army History and Heritage – Canadian Army History Website, at: http://www.army-armee.forces.gc.ca/en/about-army/history.page.

- Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Fairlie Wood, Strange Battleground: The Operations in Korea and their effects on the Defence policy of Canada, Queen’s Printer, 1966, pp. 19-30, at: http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/his/docs/Battlegrd_e.pdf.

- Desmond A. Morton, Military History of Canada, Mclelland and Stewart, Toronto, 1999, pp. 237-238. See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Canadian Army.

- Supra note 24 para 5.3.

- David Pratt, “Re-thinking the Reserves,” in Ottawa Citizen, 29 March 2011, at: https://www.pressreader.com/canada/ottawa-citizen/20110329/281865819999219.

- “Maintaining 3000 Canadian forces personnel in Afghanistan requires a pool of over 15,000. ... Additionally, about 10,000 civilian and military personnel are required at the same time, in Canada, to support the mission.” Major-General Dennis Tabbernor, “Reserves on Operations,” in Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol. 12, Issue 4, Summer 2010, p. 45, at: https://jmss.org/article/view/57926/43592.

- Parliamentary Budget Officer, Fiscal Sustainability of Canada’s National Defence Program, Ottawa, 26 March 2015, p. 1, at: http://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/files/files/Defence_Analysis_EN.pdf, and

- Jean-Nicolas Blanchet, QMI Agency, “Canada’s Military among highest paid in the world,” in Toronto Sun, 3 November 2014, at: https://torontosun.com/2014/10/30/canadas-military-among-highest-paid-in-the-world/wcm/22bc967e-663f-413f-b606-d2040ed0bd2e.

- National Defence Act R.S.C., 1985, c. N-5 (NDA) s 15(3). Reserve Force The Primary Reserve “…consists of officers and non-commissioned members who are enrolled for other than continuing, full-time military service when not on active service.” https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/n-5/page-3.html#docCont.

- The Primary Reserve provides “depth” – more of the same types of capabilities that the Regular Force already provides, or “breadth” – different capabilities not available within the Regular Force.

- Ministry of Defence, Reserves in the Future Force 2020: Valuable and Valued. London, Queen’s Printer, July 2013, p. 15, at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/210470/Cm8655-web_FINAL.pdf. See also: Independent Commission to Review the United Kingdom’s Reserve Forces Future Reserves 2020, London, July 2011, at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/28394/futurereserves_2020.pdf. See also: House of Lords Library Briefing – Armed Forces Reserves London, 18 June 2018, at: http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/LLN-2018-0068/LLN-2018-0068.pdf. - Patrick Bury and Sergio Catignani, “Future Reserves 2020, the British Army and the politics of military innovation during the Cameron era,” in International Affairs, Volume 95, Issue 3, May 2019, pp. 681–701, Oxford, UK, at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz051.

- US Congress, US Code Title 10 Subtitle E – Reserve Components, Washington, at: http://uscode.house.gov/browse/prelim@title10&edition=prelim. For an overview, see: “Reserve components of the United States Armed Forces,” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reserve_components_of_the_United_States_Armed_Forces

#Reserve_vs._National_Guard. - Department of the Army, FM 3-96.1 Brigade Combat Team Washington, 2015, pp. 1-1 to 1-12 at: https://armypubs.army.mil/ProductMaps/PubForm/Details.aspx?PUB_ID=105664.

- “Brigade Combat Team,” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brigade_combat_team.

- “List of current formations of the United States Army” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_current_formations_of_the_United_States_Army.

- For an overview, see: “Reorganization Plan for the United States Army,” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reorganization_plan_of_United_States_Army

- Supra note 19 pp. 37-41.

- NDA supra note 33 s. 31, Active Service, at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/N-5/page-6.html#h-22.

- Ibid s. 33(2)(b) Service, at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/N-5/page-6.html#h-23.

- Queen’s Regulations and Orders (QR&O) para. 9.04(3) and (4). Training and Duty, at: http://www.forces.gc.ca /en/about-policies-standards-queens-regulations-orders-vol-01/ch-09.page#cha-009-04 Emergency is defined at NDA s. 2(1) as being insurrection, riot, invasion, armed conflict or war, whether real or apprehended. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/N-5/page-1.html#h-2.

- NDA supra note 33 Part VI Aid of the Civil Power, at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/N-5/page-58.html#h-235. (May be called out by CDS (or designate) s 277 “…such part of the CF as CDS (or designate) considers necessary”)

- NDA supra note 33 s. 33(2)(a) Ordered to train; and QR&O supra note 45 para. 9.04(2) Training and Duty limited to 15 days Class B and 60 days Class A annually.

- NDA supra note 33 ss. 31 Active Service and 33(2) (b) Liability in case of reserve force, which could be broadened to allow a wider use of these provisions at the MND or delegate level.

- NDA supra note 33 ss. 60(1)(c) Persons subject to the Code of Service Discipline and 294(1) Failure to attend parade and (2) Each absence an offence with a fine of $25.00 for members and $50.00 for officers per day of training missed.

- QR&O supra note 45 Table to Article 15.01 Item 4(c) Release – Voluntary – On Request – Other Causes and Canadian Armed Forces, Military Personnel Instruction 20/04.

- Canadian Armed Forces Website Job Protection Legislation, at: http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/business-reservist-support/job-protection-legislation.page.

- Department of Justice, Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Act. At: https://www.justice.gov/crt-military/userra-statute. Department of Justice, Employment Rights of the Guard and Reserve Raleigh, NC, at: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ednc/legacy/2011/04/29/EmploymentRights.pdf.

- For example, infantry DP1 training takes 70 days for the Primary Reserve and 31 weeks for the Regular Force. The US Army infantry DP1 equivalent is 14 weeks—expanding to 22 weeks—for Active, Army National Guard, and United States Army Reserve components.

- For another discussion, see Daniel Doran, “Report of the Auditor General of Canada – Canadian Army Reserve: The Missing Link,” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 17 No.4., p. 67, at: http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol17/no4/page67-eng.asp.

- Charlsy Panzino, “3-star: More training days for the Guard as the Army struggles with readiness,” in Army Times 8 March 2017, at: https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2017/03/09/3-star-more-training-days-for-the-guard-as-the-army-struggles-with-readiness/. Sarah Sicard, “Here’s a First Look At Army National Guard Training Changes Coming in 2018,” in Task and Purpose, 19 July 2017 at: https://taskandpurpose.com/heres-first-look-army-national-guard-training-changes-coming-2018.

- Office of the Veterans Ombudsman, Myth Busting – Reserve vs Regular Force Benefits, Ottawa, 2015 http://www.ombudsman-veterans.gc.ca/eng/blog/post/286.

- The 2017 Army National Guard budget totalled US$15.6 billion for a force of 343,000. Canada’s projected Primary Reserve of 20,000-30,000 could be roughly budgeted at CA$1-1.5 billion exclusive of capital equipment acquisitions. Surprisingly, DND reported to Parliament that in 2013-2014 it spent CA$1.2 billion on the Primary Reserve, although much of that was questioned by the Auditor General in his report. Supra note 24 para 5.82

- Capping a reservist’s service to two months per year. The math obviously isn’t that simple, See Joshua Klimas, et al., “Assessing the Army’s Active-Reserve Component Force Mix.” Rand Corporation, 2014, at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR400/RR417-1/RAND_RR417-1.pdf.

- See for example: “Canadian Forces, Modernization and Reorganization: A Critical Look at the Canadian Forces Transformation Project 2007,” at: http://dtpr.lib.athabascau.ca/action/download.php?filename=mba-07/open/marshallmacleodProject-apf.pdf. Lieutenant-General Andrew Leslie, Report on Transformation 2011, Ottawa, at: http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/about-reports-pubs/transformation-report-2011.page. Lieutenant-General (ret’d) Michael K. Jeffrey, “Inside Canadian Forces Transformation,” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2010, at: http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol10/no2/04-jeffery-eng.asp.

- Leslie, supra note 59 pp. 15-23.

- Marshal of the R.A.F. Sir Arthur Harris, Bomber Offensive, 1947, Pen and Sword Military Classics, Barnsley, UK, pp. 49-51.

- Phoebe Wall Howard, “CEO Hackett: Ford Motor Company to lay off 500 US workers this week, more in June,” Detroit Free Primary Reserves, 20 May 2019, at: https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/ford/2019/05/20/ford-layoffs-dearborn/3739354002/.

- For example: a Regular Force artillery regiment could have one Regular Force and two Primary Reserve gun batteries. The current CCSB artillery and engineer components could form the core of the Army Primary Reserve Artillery and Manoeuvre Enhancement brigades.

- It would also simplify and speed up equipment acquisition, training and development of tactics, techniques, and procedures while opening lanes for greater involvement for Canadian defence industries in the US market.

- There are currently 14 combat aviation brigades in the Army National Guard. “Combat Aviation Brigade,” Wikipedia, at: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combat_Aviation_Brigade. See, generally: Department of the Army FM 3-04 Army Aviation Washington 2015, at: https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/fm3_04.pdf.

- There were circumstances, such as during Operation Medusa in Afghanistan in 2006, when artillery and LAV ammunition ran dangerously low.