This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Military History

Naval Service of Canada, CWM 19940001-980, © Canadian War Museum.

The Naval Service of Canada’s first peacetime recruiting poster.

Perpetual Interests...The Admiralty Influence on the Development of the Naval Service of Canada

by Mark Tunnicliffe

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

“It is a narrow policy to suppose that this country or that is to be marked out as the eternal ally or the perpetual enemy ... we have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”

~Lord Palmerston 1

Introduction

Shortly after midnight on 3 August 1914, HMCS Rainbow left Esquimalt in search of the German navy. More specifically, she was looking for the German cruiser SMS Leipzig, which was known to be in the vicinity of San Francisco and another, similar unit, SMS Nürnberg, thought to be in the area as well. The order to sail ordered Rainbow: “… [to] proceed to sea forthwith to guard trade routes North of the Equator, keeping in touch with Pachena, until war has been declared …”2

At the outbreak of the First World War, the main naval forces available to Germany in the Pacific were the cruisers of Admiral Graf von Spee’s East Asiatic Squadron. At the outbreak of war, two of his units, the light cruisers Leipzig and Nürnberg, had been conducting detached operations in Mexican waters as part of an international naval force evacuating civilians from Mazatlan, then besieged in the ongoing Mexican Civil War. And they were well placed to commence immediate operations against British shipping.

The Canadian cruiser that sailed, on the other hand, was by no means ready for war. Her crew was at two-thirds the normal complement, and she only had training ammunition on board – shells filled with black powder.3 Built in 1891, and now thoroughly obsolete, she was furnished with a mixed armament of two 6-inch, six 4.7-inch, and four 12-pounder guns.4 Rainbow was never intended by Canada for war, having been purchased as a ‘training cruiser,’ and she presented no real threat to the German cruisers. Her captain, Commander Walter Hose, in admitting that he would likely have come off second best in an engagement with Leipzig, later remarked: “To know where he was, exactly, at that time, would have been Rainbow’s main contribution ... My main armament was my wireless, and that only had a range of two hundred miles.”5

While Rainbow was out on her search for Leipzig, the west coast of Canada was left unprotected from any raiders that might manage to slip past her and enter Victoria, Vancouver, or Prince Rupert. Recognizing the vulnerability of his coastal towns, the premier of British Columbia, Sir Richard McBride, arranged for the emergency purchase of two submarines from the Seattle Construction and Drydock Company. The boats, available because of a contract dispute, were offered to the provincial government by the builder, and were transferred just outside Canadian territorial waters on 5 August 1914. Two days later, they were turned over to the Dominion government, effectively doubling the size of Canada’s navy.

These events marked the beginning of the combat career of a navy that had been established only four years earlier. In those four years, the readiness of the new navy had been allowed to decline to a point where its two ships were barely fit to sail (HMCS Niobe, a Diadem Class protected cruiser, was stationed in Halifax). They beg the question as to why Canada, some forty-seven years after Confederation, had neglected the issue of her maritime defences to the point that an unopposed bombardment by a single cruiser appeared to be a distinct possibility to British Columbians.

While no government was really prepared for the events of August 1914, Canada had less reason than most for warlike considerations. In fact, the British Admiralty was even less prepared, for Rainbow was the most powerful unit left available to it in the North Eastern Pacific. Indeed, the initial reason Rainbow had sailed on 3 August was to find the only two British warships in the area, HM sloops Algerine and Shearwater, and herd them back to Esquimalt before Leipzigfound them. This was not the scenario anticipated by the Canadian government. The Royal Navy (RN) was supposed to be looking after Canadian interests - not the other way around.

Canada was not ready to provide for her own maritime security. In contrast, her militia, though deficient in many ways as a fighting force, had at least been recognized as an essential responsibility of nationhood, and it had been established within a year of Confederation through the Militia Act of 1868. Canadian politicians had endlessly debated or evaded the issue of how, or whether, to provide for the seaward defence of the nation, continuing the discussion until an answer, after a fashion, was forced upon the country by the exigencies of war. The question then remains, why was it so difficult to sort out?

In their analysis of Canadian defence policy making, political scientists Dan Middlemiss and Joel Sokolsky note:

“Policy is essentially concerned with the making of choices. These choices are shaped and constrained by many factors including (1) the interests, motivations, and preferences of the various actors (individuals, organizations, and institutions), (2) the nature and interplay of the processes by which decisions are formulated and implemented; (3) the character of the environments in which these actors and processes operate.”6

They further note that the practice of not making a decision at all is a frequent Canadian habit, and that inaction is often a result arrived at after deliberate consideration – a habit as prevalent at the beginning of the 20th Century with respect to defence issues as it was at the end of the century.

One of the factors that guide a government in its defence decision-making process is the advice that it receives from its technical experts, who are clearly significant actors in the policy process. For the Canadian Government at the turn of the century, its naval advice, for the most part, had to come from the British Admiralty. Not surprisingly, the motivations, priorities, and perspectives of the Admiralty were often different from the interests of the Canadian government. This article, therefore, will examine the almost still-born arrival of the Canadian Navy in the context of the military advice offered to the government by the British Admiralty, and whose ‘perpetual interests’ were being served by it.

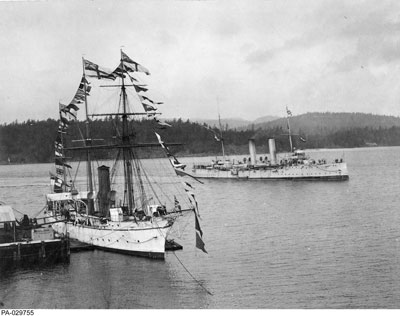

Canada. Patent and Copyright Office/Library and Archives Canada/PA-029755

HMCS Shearwater (foreground) and HMCS Rainbow, 1910.

The Admiralty Perspective

The expertise that successive Canadian governments, from Macdonald to Borden, relied upon for advice on maritime defence came from two sources. The local view was provided by the Department of Marine and Fisheries, which came into existence with Confederation in 1867. This department consolidated all the former colonial authority with respect to the regulation of shipping and navigation, ports, and fisheries regulation and protection – Canada’s domestic maritime issues. However, since Canada’s external affairs were managed by Britain, the responsibility for managing their maritime aspects lay with the British Admiralty, which performed the function of providing the expert maritime defence advice to the Colonial and Dominion governments in the same general sense that it did for the Imperial government at Westminster. However, in providing that advice, the distinction between colonial and imperial interests was not often apparent to the Admiralty, or if it was, it was not considered by them to be particularly relevant.

The Admiralty was, at the time of Confederation, trying to manage the consequences of a technological revolution. While the navy that had won at Trafalgar in 1805 was little different in its material fundamentals from that which had engaged the Spanish in 1588, technical and scientific innovation, stimulated by the Industrial Revolution, had expanded exponentially during the 19th Century. Major changes were bound to catch up with the Royal Navy, and they did so shortly after the debacle of the Crimean War. The effectiveness of the shell gun at sea was demonstrated in that war by the Russian victory over the Turkish fleet at Sinope in 1853,7 and it stimulated the development, first of armour plate upon wooden hulls, and then to all-iron construction. At the same time, sails were being replaced by steam propulsion, with engines evolving from the single cylinder, large stroke, 50-pound pressure engine introduced in 1850, to the steam turbine in 1898.8

The technological revolution had a multitude of consequences. While steam freed ships from the vagaries of the wind, it tied them to available sources of coal and repair facilities, and supply bases assumed a new importance in strategy. Fuel limitations and consumption rates also meant that firepower, protection, speed, and endurance became conflicting features of a warship and the Royal Navy found that in addressing its duties of policing the empire, those ships suited for long range operations fell short on combat capability. By end of the 19th Century, much of the RN had become a constabulary navy of limited value in a European war:

“In the prevailing uncertainty, one of the most fundamental precepts of sea power was forgotten: the idea that the sea is one, and that anything which tends to localize naval power robs it of the global mobility which is one of its greatest strengths. Contrary to this principle, naval force tended to be attached to particular stations, ships designed for special services, vessels tied to particular coasts, and the strength of naval power scattered and fragmented.”9

Additionally, with the Industrial Revolution now well-established throughout Europe and North America, Britain was being significantly challenged in a variety of economic sectors, particularly textiles, coal, and steel, most notably by the United States and Germany.10 Britain’s economic vulnerability was further exacerbated by her exposure to trade disruption as a result of the 19th Century’s version of globalization. By the 1880s, 80 percent of Britain’s wheat consumption was supplied by overseas producers, and she depended upon her export markets, not only to pay for this imported food, but for the jobs and social stability they engendered. Naturally, this ‘Achilles Heel’ had become a topic of interest to England’s perennial enemies, the French, whose Jeune École’s theory of guerre de course began striking a cord of alarm in Britain.

Thus, a combination of factors - the uncertainty of the effectiveness of the fleet, its overextension throughout the Empire, a growing sense of vulnerability at home, and ever increasing industrial and naval challenges in Europe, began to alarm the Admiralty and shake the sense of complacency in the British government and public. The attention of the Admiralty was becoming focused – at home.

The Admiralty’s Response

The Admiralty’s response to the situation, embodied in the Naval Defence Act of 1889, required gaining considerable public support, generated to some extent by alarmist “Truth about the Navy” press articles. The cost of this rebuilding program presented a challenge to the Imperial Government, stimulating discussion at the first Colonial Conference, convened in London in 1887, to draw the self-governing colonies into a debate with respect to cooperation within the Empire. Revising an earlier policy (the Colonial Naval Defence Act of 1865, which permitted colonies to build and man their own naval forces), the Conference gave the Admiralty a platform to press its case for cash contributions from the self-governing colonies as their share of the maritime defence of the Empire.11 The costs of the NDA stimulated the Gladstone government to seek savings through the reduction of that portion of the fleet deployed on foreign stations, declaring: “ … [that] we are to have a powerful fleet in and near our own waters, and that outside this, nothing is to be maintained except for well-defined and approved purposes of actual service, and in quantities of force properly adjusted.”12

That policy raised the question in the minds of the colonial governments as to how their local maritime interests would be served. The Admiralty might respond to events with a reaction squadron, permit the construction of local forces funded and supported by the colony, or they could do nothing at all. Previously it had been the latter two options that appeared to appeal to the Admiralty as Canada had discovered during the 1877-1878 Turkish-Russian War. Fearing British involvement in that war, the Governor General of Canada requested that the Admiralty make ships available for protection against commerce raiders that might disrupt Canadian shipping. In response, the Admiralty allowed that while it would make arrangements to prevent a large scale break-out, it expected that it was “… only reasonable to assume that the Canadian Government will avail themselves itself of their its own resources for the protection of Canadian shipping”13 by arming some fast merchant ships with guns provided by the Admiralty.

This evidence of British reticence in coming to Canada’s aid in a crisis stimulated a greater Canadian disposition to examine the concept of naval self-sufficiency, and subsequently, the GOC of the Canadian Militia recommended that the Dominion acquire a vessel suitable for coastal defence. The Admiralty provided the old steam corvette Charybdis, worn out from seven years on the China station. Her career in Canadian service consisted of damaging some ships in Saint John harbour when she broke loose in a gale, and the accidental drowning of two civilians who fell through a rotten gangplank. Inspection revealed that Canada could neither man the ship nor pay to operate it, and the ‘gift’ was returned, leaving behind a legacy of political wariness over the concept of a national navy.

Library and Archives Canada/C-002699.

HMCS Charybdis.

Seeking the freedom to dispose its forces as it saw fit, and to defend the colonies ‘at a distance’ where possible, the Admiralty used the occasion of the 1897 Conference to revisit the linkage between the naval subsidies already being paid by the Australian States and New Zealand, to the necessity for stationing forces in local waters, as agreed upon under the terms of the subsidies. While the Australian premiers were adamant that their payments were intended for a specific service, and insisted that a local squadron be maintained, the publication of Mahan’s first “Influence” book in 1890 (extolling the virtues of a concentrated fleet) spurred the Admiralty’s desire for a completely free hand in disposing its ships. While Canada paid no contributions, the nation still expected British support despite the latter’s warning that while it would, in theory be available in an emergency, ships might be some time in arriving. In the meantime, Canada “alone of the many parts of the British Empire, [was] absolutely without any organization for utilizing its splendid personnel in war.”14 Laurier, however, took the same line previously established by Macdonald. Because of the proximity of the United States with whom friendly relations were now well established, there was no naval threat to Canada which could not be handled by measures improvised as required.

However, a ‘new wrinkle’ in the debate on how the colonies might contribute to Imperial naval defence was raised by the Premier of the Cape Colony, who offered the cost of a cruiser to the Royal Navy – an offer not made out of altruism, but rather in recognition of the unsettled conditions in South Africa at the time. Two years later, those conditions led to the Boer War, and colonial participation in it was the major factor colouring the tone of the next Colonial Conference in 1902. Britain hoped that the feeling of imperial solidarity engendered by the war would be reflected in greater contributions to an Imperial navy unfettered in its global operations under the ‘one sea’ principle. Colonial nationalism was indeed running high, but in Australia and Canada, not in the direction the British had hoped. In the former, a feeling of self sufficiency was fostered by its recent confederation, and in the latter, an increasing confidence in relations with the United States, whose navy, battle proven in the recent war with Spain, lent increasing credibility to the Munroe Doctrine, were combined with a general disgust with British management of the war in South Africa.15 Both nations were now less inclined to defer blindly to Britain in matters military. Despite this, the Admiralty pressed harder, not only for increased contributions but also for a free hand to deploy the fleet however it saw fit, regardless of the demands of the contributing colonies.16

Eventually, the Admiralty managed to achieve an arrangement with New Zealand and Australia for increased contributions in return for a promise of more modern warships in southern waters, although not specifically tied to any national coast. While rather clumsy attempts had been made to shame the senior Dominion into greater contributions to naval defence, Laurier remained obdurate, observing that Canada’s investments in public works were a more extensive and practical contribution to imperial defence. He did allow, however, that if the Admiralty was unable to look after Canadian coasts directly, then his government would look into naval defence, as well as the land forces it currently provided.17 Laurier seems to have been forced to be more direct about his intentions than he had intended, but the Admiralty received his comments coolly, maintaining that the establishment of individual colonial navies was a fragmentation of imperial naval effort, and liable to defeat.

The Admiralty executed its plans to concentrate the Royal Navy by eliminating its Pacific squadron and most of its forces in the Western Atlantic. While some Canadians took these moves to mean that there was little international friction at all, others took it as a further indication that Britain never really intended to defend the country, and that Canada should instead rely upon the Americans. To Australians, who noted the withdrawal of the last five British battleships from the Pacific, and British reliance upon their 1902 cooperation treaty with Japan for security in the Pacific, the Admiralty’s actions represented a betrayal of the agreement on contributions that they had bitterly debated two years before. Public pressure in Australia to acquire a national navy could no longer be ignored.

The Admiralty finally bowed to these political realities at the 1907 Colonial Conference, conceding that the self governing colonies might organize a navy as long as it came under Admiralty control in wartime. A force of torpedo boats and destroyers, after all, might have some utility in defending local installations and ports, relieving the RN of the necessity of providing for such defence overseas. Nevertheless, this did not stop the Admiralty from continuing to press for contributions, ignoring Laurier’s protestations that Canada’s contribution would continue to consist of its Fisheries Protection Service and infrastructure arrangements.18

That said, the concession by the Admiralty was a significant change, and it was used by the Australians to request technical advice on the type of fleet which might be useful. In 1908, the Admiralty conducted a survey outlining the costs, manning and career implications, and the infrastructure requirements for an Australian force of nine submarines and six destroyers.19 The Admiralty took this opportunity to offer similar advice to Canada on the occasion of the 1908 upgrading of the defences at Halifax, noting that, as fast moving torpedo craft could evade the fortress’ guns, especially under the cover of fog, a destroyer flotilla should be included in a Canadian defence scheme.20

Between the Conference of 1902 and that of 1907 another naval revolution had occurred, and its name was Admiral “Jackie” Fisher. And this new First Sea Lord was the right man in the right place as far as a frugal Liberal government was concerned. Fisher promised to reduce the estimates with a four point21 program that included the elimination of some 154 ships of dubious fighting value, including most of the traditional foreign station gun boats, and a further concentration of the fighting fleet at home. Relying upon the increasingly friendly attitude of the Americans, the 1902 Anglo-Japanese defence treaty, and the fact that Canada had no Pacific trade worth the Admiralty’s attention, Fisher reduced the RN Pacific presence and encouraged the idea of the Dominions building their own fleets to reduce the pressure upon the RN, declaring: “We’ll manage the job in Europe. They’ll manage it against the Yankees, Japs and Chinese, as occasion requires out there.”22

Another of Fisher’s innovations was the introduction of a new combat ship design concept - the all big gun Dreadnought Class battleship23 which, however, introduced another problem to the Admiralty. It was such a superior design that it essentially made all previous battleship designs obsolete, reducing Britain’s hitherto unassailable numerical advantage in battleships to an effective advantage of one, and exposing her to a shipbuilding competition from rivals. This effectively nullified the savings that Fisher had achieved by his other reforms. Britain had to enter a furious building race just to keep ahead of an industrially potent Germany.

By 1909, this situation had reached crisis proportions and the Admiralty was claiming that within the next four years, the Germans would surpass Britain in the number of Dreadnought class units. Fisher stirred up a propaganda battle that culminated in the public “We want eight and we won’t wait!” demands for more building. The government gave in to the furore and authorised the building of additional units; a reaction caustically summarized as: “The Admiralty had demanded six ships, the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight.”24 The Admiralty campaign, intended for home consumption, caused immediate reverberations in the Dominions. New Zealand immediately cabled the offer of the price of a dreadnought battleship, and the Australian government was challenged by its opposition to match the offer. Laurier was also besieged by similar demands from both Liberals and Conservatives in the House, and also by the public to follow suit.

Laurier, fearing the Quebec backlash that making such an offer would risk, ventured at this point to offer the construction of the torpedo boat navy suggested by the Admiralty in 1907. This proposal, although still too much for Quebec Nationalistes, could be defended on the basis that it could only be used for local defence, and Laurier built a fragile consensus in the House on this premise, leaving open the option for a contribution if a true ‘crisis’ should ever erupt by offering to consult the Admiralty as needed.25

However, the Admiralty, unsure if Japan would renew its treaty with Britain in 1911 when it was due to expire, declared that its advice to Australia and Canada on building a torpedo boat navy was now incorrect and it would result in colonial fleets limited in their utility for cooperating with the Imperial fleet. Instead, the Admiralty proposed that the Dominions establish navies consisting of a “fleet unit.” Such a unit would consist of an Indomitable Class battle cruiser, three light cruisers, and supporting destroyers. It proposed an Australian and New Zealand squadron and a Canadian ‘unit’ for coastal defence and commerce protection. To discuss this proposal, a conference was called for the summer of 1909, which, to his chagrin, Laurier could not avoid, due to his earlier commitment to consult with the Admiralty.

Library and Archives Canada/Admiral Sir Charles E. Kingsmill collection/C-104488.

Rear-Admiral Sir Charles Kingsmill.

The Definition of a Navy

The 1909 conference on defence, chaired by British Prime Minister Asquith, was the ultimate stimulus for the creation of a Canadian navy. It was attended on Canada’s part by the Minister of Militia and Defence, F.W. Borden, the Minister of Marine and Fisheries, L.P. Brodeur, and their senior advisors, Major-General Lake and Rear-Admiral Kingsmill.26 The British adapted to the various national approaches to naval defence with some conditions. They accepted New Zealand’s approach of funding specific construction projects for the RN and specified a battle cruiser (eventually HMS New Zealand). They also accepted the national aspirations of Canada and Australia to establish their own navies, but insisted that these be structured “… under regulations similar to those established in the Royal Navy, in order to allow exchange of personnel and operational union between the British and Dominion services, and, with the same object, the standard of vessels and armaments would be uniform.”27

The Conference indicated that squadrons to be maintained in the Pacific would consist of three fleet units, which would comprise an Indomitable Class “large armoured cruiser,” three Bristol Class light cruisers, six River Class destroyers, and three “C”-type submarines. The key was to develop a navy which was big enough to be self-sustaining and capable of immediate integration into the Royal Navy in wartime, and having the range and speed to coalesce into a formidable force, if necessary. The Admiralty proposed three such fleet units: an Australian one in local waters, a British unit formed around the battle cruiser donated by New Zealand operating out of Hong Kong, and another British unit in the Indian Ocean. Originally, it had been hoped that Canada would build two such fleet units, one on each coast, with Fisher insisting that the first Canadian ship be a battle cruiser stationed on the West Coast. However, the Canadian delegates were wary of the choice of a battle cruiser at all, and Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty (1908-1911), overruled Fisher, and agreed to propose to the Canadians a navy which would fit their budget. In a ‘side-bar’ meeting with the Canadians, the Admiralty presented proposals for a fleet consisting of four improved Bristol Class cruisers, a BoadiceaClass small cruiser, and six destroyers. A cheaper option was also outlined that retained the Bristols and four destroyers. The Admiralty also proposed to loan Canada two Apollo Class cruisers for training purposes until the new ships were built.28

The proposed force structure appears to have been constructed with its suitability for Admiralty purposes paramount. While the Conference minutes do not expand upon the reasons for the ships chosen, the improved Bristols, of 5250 tons displacement and eight 6-inch guns main armament, were of sufficient size for scouting duties in support of a main fleet.29 The Boadicea Class cruiser appears to have been intended to act as a destroyer leader for the destroyers, suggesting a strike role for that squadron.30

Laurier now recognized that he had stalled about as long as he could on the naval question, and, building upon a resolution made by an opposition member, George Foster, and establishing a fragile consensus on the issue with the Conservative opposition, he proposed the formation of a Canadian navy. Thus, with the proclamation of the Naval Service Act (NSA) on 4 May 1910, the Canadian Navy was born.31

A Failed Procurement

Tenders were submitted shortly thereafter for the ten-ship fleet proposed by the Admiralty,32 but, in the interim, the new navy purchased two obsolescent ships for training purposes. These were Rainbow, and the much larger Niobe, selected over a second Apollo Class ship for its capacity as an accommodation ship for trainees. However, shortly after the passage of the NSA, Laurier’s fourteen-year-old government was out of office. After a few cruises, including one in which the Niobe ran aground and had to be towed back to Halifax, the ships were tied up, their British training cadre returned home, and many Canadians deserted.

DND SU2007-0281-05a.

HMCS Niobe at Daybreak, by Peter Rindlisbacher.

Robert Borden’s successor government, a fractious coalition of imperialists and Nationalistes, immediately cancelled the tenders for the proposed warships, and announced its intention to repeal the NSA. However, while it was relatively easy for Borden to repudiate it under the influence of strident cries for him to take stronger action, the Quebec wing of his own party remained opposed to any action with respect to a national navy. Consequently, he did not announce an alternative policy, and this presented the Admiralty a second chance to ‘trot out’ its preferred option:

“ ... as it became clear that the Dominion government had no real program, an opportunity for the Admiralty to influence developments emerged … In the circumstances … the Admiralty were free to reach their decisions, ‘having regard only to strategic considerations and no longer to considerations of what will best please Canada. (author’s italics)’”33

At the same time, a new naval panic was taking shape in London. The German Naval Law of 1912 had increased the readiness of their High Seas Fleet, forcing even greater concentration of the Royal Navy in home waters, drawing down assets from the Mediterranean, and exposing British interests in the region to the burgeoning Italian and Austro-Hungarian fleets. Borden’s proclivity for making cash contributions to the British in lieu of a national fleet aligned well with that of Winston Churchill, now First Lord of the Admiralty, who strongly opposed the concept of separate Dominion navies. The latter took the opportunity offered by a visit by Borden to London in 1912 to convince him that an emergency contribution was needed from Canada to fund three Dreadnoughts for deployment in the Mediterranean.

Library and Archives Canada/C-002082.

Churchill and Borden leaving the Admiralty, July 1912.

This proposal appealed to Borden as a “ready-made naval policy,” and, armed with two Admiralty memoranda,34 Borden determined to sideline the Liberal policy of gradually building up a national navy. On 5 December 1912, he proposed a Naval Aid Bill, introduced by a speech largely taken from the unclassified version of the Admiralty memorandum, which provided $35 million for the construction of the three battleships. The degree of his departure from the Laurier program, and his own conception of Canada’s position in defence priorities was illustrated in his following observation:

“I am assured that the aid which we propose will enable such special arrangements to be consummated that, without courting disaster at home, an effective fleet of battleships and cruisers can be established in the Pacific and a powerful squadron can periodically visit our Atlantic seaboard to assert once more the naval strength of the Empire which primarily safeguards the Overseas Dominions.”35

In response, the Liberals charged Borden with backtracking, and insisted that there was no danger that Britain could not handle. Laurier did offer to support the construction of two full fleet units if the government deemed the situation warranted, as long as the units remained Canadian.36 The debate wore on through the winter of 1913, until, by use of closure, Borden forced his bill through the House. However, the Liberal-dominated Senate promptly defeated it, leaving Borden’s government with essentially no viable policy at all.

The battleships offered under the terms of the bill (they would have been super-dreadnoughts of the Queen Elizabeth Class) would have represented a significant augmentation to British naval strength, and Churchill proposed employing them as an Imperial Flying squadron composed of New Zealand, Malaya (a battleship funded by the Federated Malay States), and the three Canadian funded ships for deployment anywhere within the British Empire. Of course, the squadron, based in Gibraltar, would have been far better placed for addressing the Admiralty’s concerns with respect to the Fleet's situation at home. Any pretence of addressing the Dominion’s concerns had faded.

In the ensuing debate between Liberal and Conservative naval policies, which were alternately supported and condemned by the Admiralty, no decision was made and by the summer of 1914, the Borden government:

“ … had not implemented the Naval Service Act … Nor had it been able to start its immediate project, born of the German naval threat and a fear of war. When this fear had become a reality, therefore, there were no Canadian Bristols and destroyers, nor fleet units, nor contributed Queen Elizabeths, either built or building.”37

The policy that would guide the Canadian navy through the war was effectively Macdonald’s old policy of improvising in a crisis, pinned to the framework of the despised Laurier Naval Service Act. Canada entered the war with two elderly training cruisers, some useful dockyard infrastructure, and a moderately efficient harbour defence organization.

The Canadian Perspective

Government policy development with respect to its maritime defences was clearly influenced by its perception of the challenges it faced. The one realistic challenge with which Canadians had to contend was that posed by the United States, and, from a maritime perspective, that ‘threat’ to Canadian interests was mainly economic and related to fishing rights. The nation therefore addressed this challenge through the development of a ‘navy’ tailored to the purpose – the Fisheries Protection Service. Born of earlier measures taken by the provinces to enforce fisheries treaties with the US, the FPS, flying the Canadian Blue Ensign, had evolved into a smart little ‘quasi-military’ outfit with uniformed personnel and a fleet of fourteen38 patrol vessels. That this fleet was uniformly supported by Canadian governments and the public is suggestive that its structure and composition were viewed as a realistic response to the Canadian perception of the threats to Canada’s interests.

With respect to developing a ‘military’ navy, there were three possible options open to a Canadian government: contribute to the Imperial Navy; build a national navy; or do nothing at all. The Canadian public fervently supported all three – variously, and in different parts of the country. On the west coast, the public demanded a subsidy policy, but Victoria, smarting from the withdrawal of the Royal Navy presence at Esquimalt, entertained the illusion that subsidies would attract it back. In Toronto, with potential profits to be made from shipbuilding, activists promoted the idea of building a navy around armed merchant ships.39 Quebec opinion, led by Henri Bourassa, the journalist and MP, wanted to have nothing to do with either a Canadian navy or the subsidies, which might involve Canada in Imperial wars. Bourassa seemed particularly sensitive to the types of naval vessels under discussion during the debate on Laurier’s Naval Bill, noting that both the destroyer and cruiser classes under consideration had too great a potential for integration with a British naval force.40

Conclusion

This was the Canadian policy-making environment into which the Admiralty injected its advice and lobbying effort. While it would not be true to say that there was no-one in the Admiralty who could comprehend the Canadian situation (some, such as First Lord McKenna were sympathetic), British naval opinion seemed generally oblivious to, and impatient of, the Canadian situation. Furthermore, the Admiralty’s constantly changing advice in the Canadian political environment almost guaranteed that no decision would be reached – it was too patently self-serving and increasingly oblivious to the aspirations, perceptions, and needs of the Dominions. Laurier was able to cope with it, delaying a decision until the advice and political climate coalesced on the solution that he saw matched Canada’s needs and aspirations. Borden, on the other hand, proved to be less capable of evading Admiralty pressure.

In the Pacific as well, the Admiralty was ‘caught flat footed’ by the assassination at Sarajevo. While the Canadians had never intended to participate in the Pacific fleet unit plan, the Australians and New Zealanders had done their part. The British, however, failed to contribute any new units. Much to the alarm of New Zealand, the battle cruiser funded by that nation’s taxpayers, after a few flag waving cruises, had been withdrawn to British home waters with Churchill noting: “A battle cruiser is not a necessary part of a fleet unit provided by the Dominions ... the presence of such vessels in the Pacific is not necessary to the British (Author’s italics) interest.”41 Of course, the presence of such units in the Pacific would have been greatly in the Dominions’ interests, particularly early in the war. Indeed, Churchill’s assertion that the pre-dreadnought battleships and “other armoured cruisers [the only significant British units stationed in the Pacific and Indian Oceans] which are quite sufficient for the work they will have to do,”42 would be proven false when they met von Spee’s squadron at the Battle of Coronel, 1 November 1914.

And in the North Pacific, a Canadian training ship would set out on a search for two lost British gunboats …

Norman Wilkinson, Canada’s Answer, CWM 19710261-0791, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

Canada’s Answer, 1914, by Norman Wilkinson.

![]()

Commander (ret’d) Mark Tunnicliffe is currently a Defence Scientist with Defence Research and Development Canada at National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa.

Notes

- Lord Palmerston to the House of Commons, 1848.

- G.N. Tucker, The Naval Service of Canada, Vol.1, (Ottawa: Kings Printer, 1952), p. 265. Pachena was a wireless telegraphy station.

- M.L. Hadley and R. Sarty, Tin Pots & Pirate Ships, (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1991), p. 89.

- T.A. Brassey (ed), The Naval Annual - 1911, (London: J. Griffin & Co, 1911) , p. 209 shows Rainbow’s initial armament. M. Tunnicliffe, “Rainbow’s Guns – What and When,” in The Northern Mariner, Vol. XVI, No. 3, pp 33 – 51, details the changes made to her armament during Rainbow’s Canadian service.

- Lawrence, H, Tales of the North Atlantic, (Toronto: McLelland & Stewart Ltd, 1985), p. 34

- Dan W. Middlemiss and Joel J. Sokolsky, Canadian Defence - Decisions and Determinants, (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovtch Canada Ltd, 1989), p. 4.

- A.J. Marder, British Naval Policy, 1880 - 1905, The Anatomy of British Sea Power, (London: Putnam & Co, 1940), p. 4.

- D.K. Brown, “Wood, Sail and Cannonballs to Steel, Steam and Shells, 1815 – 1895,”in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, J.R. Hill, (ed), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp 200 - 226.

- D.C. Gordon, The Dominion Partnership in Imperial Defence, 1870 - 1914, (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1965), p. 51.

- P. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, (London: Fontana Press, 1985), pp 249 - 354.

- J.E. Kendle, The Colonial and Imperial Conferences, 1887 - 1911, (London: Longmans, 1967), p. 9.

- Gordon, p. 56.

- Tucker, p. 63.

- CDC Memo #59 quoted in Gordon, p. 105.

- As quoted in Gordon, p. 145. The Age, Melbourne, Australia, 1 Jan 1902, commented: “… never was it more conspicuously true that the British Army is largely led by asses ...”

- Colonial Office Misc No. 144 (Conf), Minutes of Proceedings laid Before the Conference, 4 July 1902, p. 19, as quoted in G.H.Gimblett, Tin Pots or Dreadnoughts?: The Evolution of Naval policy of the Laurier Administration, 1896 – 1911, MA Thesis, Trent University, 1981, p. 64.

- Hadley/Sarty, p. 13.

- In trying to shame the Canadians into offering money, Lord Tweedmouth, the First Lord, had tabled cost estimates from the Admiralty and the Dominions. In the Admiralty estimates, he included infrastructure and domestic operational (fisheries patrol) costs, but left them out in the figures he represented for Canada. L.P. Brodeur (Canadian Minister for Marine and Fisheries) left no doubt in his rebuttal that Laurier was not pleased with the duplicity. N.D. Brodeur, “L.P. Brodeur and the Origins of the Royal Canadian Navy,” in J.A. Boutillier, The RCN in Retrospect, 1910 - 1968, (Vancouver: The University of British Columbia Press, 1982), pp. 20-21.

- Gordon, pp. 218-219.

- B. Gough and R. Sarty, “Sailors and Soldiers: The Royal Navy, the Canadian Forces and the Defence of Canada 1890 – 1918, ” in A Nation's Navy, p. 120.

- A.J. Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, Vol. 1 - The Road to War 1904 - 1914, (London: Oxford University Press, 1961), pp. 28-36.

- As quoted in P. Kennedy, “Naval Mastery: The Canadian Context,” in The RCN in Transition, 1910 - 1985, W.A.B. Douglas ,(ed), (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1988), p. 20.

- A.J. Marder, British Naval Policy, p. 487. Actually, Fisher's revolutionary ship concepts had two components: one was the Dreadnought Class battleship, with a unitary main armament and heavy armour. The other was the battle cruiser, which shared all the attributes of the battleship except that it shed much of its armour protection in exchange for range and speed.

- Gordon, p. 221.

- Ibid., pp 226-230; also Hadley/Sarty , pp 26-27.

- The GOC of the Canadian Militia and the head of the Canadian Fisheries Protection Service, respectively.

- The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia #64 - C15927 d. 17 November 1909, Conference with Representatives of the Self Governing Dominions on the Naval and Military Defence of the Empire 1909, p. 19.

- Conference on ... Defence of the Empire, pp 25-27. A similar meeting was held with the Australians with a more ambitious proposal.

- Brassey’s Naval Annual, 1912, p. 35.Tucker, p. 136, notes that Laurier had informed the House that the Bristols and the River Class destroyers had been selected on the basis of their sea keeping qualities, a fact that an opposition member, Henri Bourassa, used to indicate that Canadian requirements and uses for a fleet were ignored in the Admiralty recommendations.

- Tucker, p. 164. Brasseys Naval Annual, 1911, p 12.

- R.H. Gimblett, “Reassessing the Dreadnought Crisis of 1909 and the Origins of the Royal Canadian Navy,”, in The Northern Mariner, Vol. IV, No. 1, January 1994, pp 35-53.

- The Boadicea seems to have been dropped from the 11 ship fleet option that was selected by Laurier.

- Gordon, p. 258.

- Tucker,Appendix VIII.

- The Naval Aid Bill - A Speech Delivered by the Hon. R.L. Borden - 5 December 1912.

- “Canada and the Navy” - A Speech by W. Laurier in moving Amendment Ten to the Naval Aid Bill in the House of Commons, 12 December 1912.

- Tucker, p. 211.

- Boutillier, Appendix 1. See also T.E. Appleton, Usque ad Mare - A History of the Canadian Coast Guard and Marine Services, (Ottawa: The Queen's Printer, 1969), pp 71-80, for the FPS influence on the origins of the Canadian Navy.

- CGS Vigilant, a small fisheries cruiser, was built at Poulson's Iron Works in Toronto - the first modern warship constructed in Canada.

- Tucker, p 136.

- As quoted in Gordon, p. 290.

- Ibid.