This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Views and Opinions

Major Charles Fraser Comfort, The Hitler Line, CWM 19710261-2203, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

The Hitler Line, by Charles Fraser Comfort, 1944.

“What is to be Done?” The Future of Canadian Second World War History

by J.L. Granatstein

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

“What is to be Done?” was the title of Lenin’s book/pamphlet published in 1902, well before he seized power in Russia. The Bolshevik leader was calling for the formation of a cadre of professional revolutionaries, a vanguard to direct the efforts of the working class. Only a revolutionary party, only an educated elite, Lenin maintained, could lead a scientific socialist revolution.

I am no Leninist - in fact, I’m a committed Groucho Marxist - but I do believe that only a group of dedicated professional historians can take back Canadian history. Increasing numbers of ‘Canadianists’ are beginning to bemoan the state of Canadian history in the universities, and to suggest that it is being all but driven out of history departments by declining faculty numbers and dropping enrolments. Canadian history, one friend says, is becoming the subject that dare not speak its name. Certainly, there are some signs that the concerns are correct across the country. Why? There will be many answers, but I point the finger at tiny particularist courses and narrow, boring, ideologically dense, and badly-written books and articles. Francophone plumbers in North Winnipeg. The first female dentist in Moose Jaw. A Marxist history of Canadian identity in the 1960s. I am only making some of this up. Women’s history, labour history, cultural history ought to be intrinsically interesting to a wide reading public. It certainly has not become so.

But what is striking is that wherever Canadian military history is taught, the situation, certainly in terms of enrolments, appears to be very good. There are lineups at the University of New Brunswick where Marc Milner teaches, at Wilfrid Laurier University with Terry Copp and Roger Sarty, at the University of Western Ontario with Jonathan Vance, and at the University of Calgary with David Bercuson and a dozen others of his colleagues, to cite by name only a few. Moreover, while astonishingly little of note is being published in most areas of Canadian history, there are more books being published than ever before in Canadian military history, more, I believe, than in any other field of Canadian history. The University of British Columbia Press’s terrific series with the Canadian War Museum (and the Museum’s support for publications by the Gregg Centre for the Study of War and Society at the University of New Brunswick, and for Canadian Military History at Wilfrid Laurier University) deserves special mention, but so do McGill-Queen’s University Press, University of Toronto Press, Robin Brass Studio, Douglas&McIntyre, Vanwell Publishing, the Dundurn Group, and the extraordinary volume of books produced by the Canadian Defence Academy, based at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario. Very simply, there is a flood of good scholarly and popular military history coming from trade and university presses. And all this is happening when relatively few universities even teach military history at all. The largest numbers of academic military historians in one city, the extraordinary gathering at the University of Calgary excepted, are located, not in academic institutions, but at the Directorate of History and Heritage at National Defence Headquarters, and at the War Museum in Ottawa, both of which have long been the spawning ground for the best practitioners of present Canadian military history.

What is clear is that students, the reading public, and publishers want Canadian military history, even if most of the university history departments think it ‘old hat’ and boring. They are wrong - the theory-laden social/cultural/gender historians, slowly killing Canadian history in the universities and writing textbooks on Canada that completely omit the nation’s military history, are now the ones well behind the curve. At some point, a few bold department chairs may even decide to hire a military historian or two to get their enrolments back up. Canadian military historians have become the revolutionary vanguard, using the tools of the new military history with great effect.

Mr. Caven Ernest Atkins, Forming Bulkhead Girders, CWM 19710261-5657, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

Forming Bulkhead Girders, by Caven Ernest Atkins, 1942.

But enough preening. Lenin’s title “What is to be Done?” can also mean: what remains to be done? What does this present large generation of Canadian military historians need to turn to in the next decade when it looks at Canada’s part in the Second World War? Let me talk in broad strokes about books and research, and let me put my remarks in the way historians ought to think of Second World War history - the entire political, industrial, economic, social, cultural, and military story of Canada in the war.

I will begin with the political sphere first, which is where I began my own research more than 45 years ago. There are only two scholarly books that try to deal with the whole of the Canadian government during the war - Charles Stacey’s Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada 1939-1945, and my Canada’s War: The Politics of the Mackenzie King Government, 1939-1945. Stacey’s official history came out in 1970, and my book, five years later. In other words, it is 35 years since anyone tried to look at the overarching subject of how Canada fought the war. Given the availability of new sources and the different perspectives now available, that is far too long. We badly need a new look at Canada’s war.

Similarly, there is no biography of Mackenzie King when he was the wartime prime minister. There must be five hundred books on each of Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt as war leaders, but there is nothing on King, who ran the massive Canadian war effort. It is no longer sufficient to talk about King as if his dog and his table-rapping sessions with mediums were all there was to him. Why did he act as such a ‘colonial choir boy’ on so many issues? How did he manage his Cabinet? How did he lead on such issues as the political management of French Canada and the introduction of social welfare, to cite only a few? Why did King hang back in getting a voice in strategy for Canada? Did no one else in the government think of national strategy in Canada during the Second World War? The war effort was vastly greater and better organized in all aspects than that in the Great War, but do Canadians know this, or know why it was so? Has their image of Mackenzie King affected how they think of the two wars? And is it not time to change this to the reality? How could such a biography remained unwritten? This is one subject that, if done well, will make its writer a great scholarly reputation.

Nor is there a study of the Cabinet War Committee, or biographies of King’s Minister of National Defence, Colonel J. Layton Ralston, or of Charles ‘Chubby’ Power, the Air Minister. There is one good study of the Navy Minister, Stephen Henderson’s Angus L. Macdonald: A Provincial Liberal, published in 2007, and Robert Bothwell and William Kilbourn’s very good examination of the ‘Minister of Everything,’ C.D. Howe: A Biography, published 30 years ago. But these are all subjects crying out for examination or re-examination. There should also be a good, solid examination of wartime public opinion and new studies of the Liberal, Conservative, and CCF parties during the war.

We also need a military history of Newfoundland from 1939 to 1945, where Canada, the United States, and Britain all had interests and bases. How did they get on? Not very well, is the answer, but no-one has explored this fully. Peter Neary’s fine book, Newfoundland in the North Atlantic World 1929-1949 (1996), and David Mackenzie’s Inside the North Atlantic Triangle: Canada and the Entrance of Newfoundland into Confederation, 1939-1949 (1986), do the political-economic side very well, but neither asks why military enlistment in the other North American Dominion was so low in percentage terms. This needs full examination. Did everyone on the island decide to stay home and take a job at an American or Canadian base?

Nor are there serious studies of Canada’s industrial, agricultural, and timber, mineral, and mining effort. There are works in train on the aviation industry and shipbuilding, but if, as I believe, Canada’s vehicle production was the country’s key contribution to victory, why is there no study of the wartime automobile industry? We should have a full appraisal of what Canadian industry did overall, how it did it, and who directed the task. Did everything run smoothly in the Department of Munitions and Supply? We don’t know - there is no serious scholarly study of the Department. Or were the Ram tank, the inadequate Royal Canadian Navy radar sets, and the expensive, drawn-out saga of building Lancaster bombers at Malton, Ontario, more the norm than the exceptions? Was Howe the organizational genius we are always assured he was? What was the impact of the war on modernizing Canadian industry and agriculture? What did the nation’s economic elite believe they wanted - and got - out of the war? What impact, if any, did they have on shaping wartime policy in their own interests? We need a full historical study of Canada’s economic war, its Wartime Prices and Trade Board (there is one unpublished dissertation done by Christopher Waddell at York University almost 30 years ago), its treatment of labour, unionized and not, and how Canada raised the funds needed to fight the war and give away billions in gifts and Mutual Aid. We need a full study of women in the war - why so few, not so many - went into the factories and why they returned in such large numbers to domesticity in 1945. Ruth Pierson ably covered women in uniform in her “They’re Still Women After All”: The Second World War and Canadian Womanhood, published in 1986, but more remains unwritten.

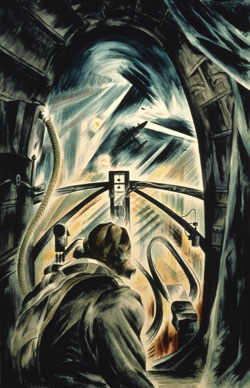

Flight Lieutenant Carl Fellman Schaefer, Bomb Aimer, Battle of the Ruhr, 1944, CWM 19710261-5121, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

Bomb Aimer, Battle of the Ruhr, 1944, by Carl Fellman Schaefer, 1951.

There is also much more to be said on re-establishing veterans, more than Peter Neary and I could get into the essays we edited in The Veterans Charter and Post World War II Canada (1998), although Neary is now writing on this topic. Why, for example, did no Second World War veteran become prime minister? What does that say of us? What influence did the vets have on Canadian life, good or bad? What role did veterans organizations play, contrasted with that after 1918?

We desperately need a good examination of the entire area of wartime mobilization. Why was it so light in its effects? What was the contribution of ethnic groups—of German-Canadians, Italian-Canadians, Ukrainian-Canadians and others? Did - as I believe - British-Canadians disproportionately fight the war on their own as they had done in 1914-1918? I ask this because I continue to wonder why my father - and his four brothers--neither volunteered nor got called up? Why did my mother stay at home during the war? Why did Pierre Trudeau not get called up? Why was he permitted to leave Canada to go to Harvard in 1944? Jeffrey Keshen’s fine study, Saints, Sinners and Soldiers: Canada’s Second World War (2004), looks at the grimy underbelly of some domestic areas, including black marketeering, the first major examination of the whole Canadian home front, including - for the first time in a researched way - the lives of children growing up with fathers overseas and with their mothers working.

Unfortunately, there are no book-length wartime regional economic studies. We need studies of Ontario, the Maritimes, the West, British Columbia, and Quebec. And as Roger Sarty and B.D. Tennyson’s Guardian of the Gulf: Sydney, Cape Breton and the Atlantic Wars (2000) and Serge Durflinger’s Fighting from Home: The Second World War in Verdun, Quebec (2006) confirm, we could use more first-class city histories.

Above all, one of the great gaps in all Canadian history is the absence of a study of Quebec and the war, a big, important book that would examine how and why francophones acted and reacted as they did during the war. (We need this for the First World War as well.) The young Pierre Trudeau thought the war another imperialist conflict driven only by the British and their Anglo-Canadian supporters. How could someone so intelligent think that, and so misread the Nazis? What does that say of francophone attitudes? How many French Canadians actually volunteered, and why? The estimates of those who served, volunteers and conscripts, range from 90,000 Québécois to 200,000 French-speaking Canadians. Who did and did not volunteer, and why? John Macfarlane’s Triquet’s Cross: Some Societal and Political Dimensions of Military Heroism, a study of Captain Paul Triquet, VC, is one attempt to examine Quebec in the war through a unique lens, but it does not succeed. Durflinger’s very fine study of Verdun does succeed, and it provides some answers for one Montreal suburb. We need a study of the whole province, and, indeed, of all French-speaking Canada that is hard-eyed, hard-edged, and willing to tell the truth. It would be best if it was written by a francophone, but it still may be too contentious a topic for anyone in Quebec to tackle. Someone must. This is another book that will make a great career.

While there are specific small areas that need coverage, most wartime foreign policy history has been written. With the multi-volume works of Charles Stacey (Canada and the Age of Conflict) and John Holmes ((The Shaping of Peace) and detailed studies by many others, as well as a host of biographies and memoirs by and on men such as Escott Reid, L.B. Pearson, Norman Robertson, and, with a study of O.D. Skelton forthcoming from Norman Hillmer, there is likely enough fine recent work on most subjects. But that said, there is still a requirement for full-scale histories that bring together the whole story of Canada-United Kingdom and Canada-United States military, economic and diplomatic relations, or better yet, a Canada-U.S.-U.K. study. R.B. Bryce’s Canada and the Cost of World War II (2005), his post-mortem account of Canadian international finance during the Second World War, is a good starting point.

On the military aspects of Canada’s war, history is still not well served. There is The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, which is first rate in research, if sometimes strangely skewed in argument. Even so, it deliberately did not look at the 55 percent of RCAF aircrew overseas who served in Royal Air Force squadrons, or as groundcrew or as women in the RCAF. Those are very large gaps. We have the superb Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War well underway. There are the three volumes of the Official History of the Canadian Army ,which are first class, but now 50 years old or more. These should be re-done or, at least, the subjects should be tackled by non-official historians. We do have much good work on the RCN and the RCAF by academic and popular historians, but there are still no major books on how the RCN was raised from nothing to 100,000 men and 400 ships in a few years (Richard Mayne’s Betrayed: Scandal, Politics and Canadian Naval Leadership (2006)) suggests there is much more to this than we yet know) and how a half-million soldiers and airmen were transported to Britain. Where is the thoroughly researched and readable book on how the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was set up and run, and its massive impact upon the country? What did it mean to have Brits, Aussies, and Kiwis in Yorkton, Saskatchewan and Springbank, Alberta? And were there really street brawls in Quebec City between airmen and civilians? We have some fine operational histories by able scholars, not least Terry Copp, Brian Reid, and Jack English, but readers and researchers still need to know more about how the army was recruited and trained. What were the motivations of home defence conscripts, or of volunteers for overseas service? What were public attitudes to home defence ‘Zombies’ during and after the war? That the Canadian Legion refused to admit even conscripts who fought overseas until 1950 suggests that feelings against those who refused to volunteer remained strong after the peace.

Mr. Peter Whyte, Control Tower, CWM 19710261-5888, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

Control Tower, by Peter Whyte, 1944.

I also believe that the overall Canadian experience in the Second World War may be similar to that of the other Dominions. Is there not room for a comparative history (or perhaps first a large international conference) on the efforts of the Dominions, all of which experienced major problems in the field? On recent trips to Australia and New Zealand, I was struck by the need for comparative research.

To change tack, it does not serve much purpose any more to blame London for the disasters at Hong Kong and Dieppe. Instead, we need to do as Béatrice Richard did in La mémoire de Dieppe: Radioscopie d’un mythe (2002), and examine what the debacle at Dieppe meant and means still to Canadians’ memory of the war, their relations with Britain, and their sense of themselves. But that does not mean that we should not look even more closely at the state of Canadian training and the lack of our own military and diplomatic intelligence capabilities. Historians also need to ask generally if high casualty rates are a measure of effectiveness - or of ineffectiveness. And the real question scholars must ask is why the Canadian services were so colonial during the war. Canadians brag about how much better and more innovative the Canadian Corps was than the British in the Great War, but during the Second World War the Canadian Army slavishly followed the British lead in operations, training, and doctrine. Why? Jack English’s fine 1991 book (The Canadian Army and the Normandy Campaign) on the failings of the army in Normandy gave some answers, but much more work is needed here.

And it is not only the army. How can a flat-out colonial issue like Canadianization in the RCAF arise more than a decade after the Statute of Westminster? How did Canada allow the Royal Navy to fob off the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) with lousy equipment for so long? Why did Ottawa not demand that the Canadian services fight together? Why did the government allow the RCAF’s tactical fighters to support British, not Canadian, troops in Northwest Europe? (Or l Canadian Armoured Brigade to not support l Canadian Division in Italy?) Why does Canada produce a superb fighting soldier like Sir Arthur Currie in the Great War, and a political-military bureaucrat like Harry Crerar during the Second World War? To raise questions like these is, among other things, to ask what the Great War did to shape Canada’s Second World War.

I do not believe in the ‘great man’ theory of history, but there is no doubt that biography offers a way into the past. Happily, we do have a good study of Crerar, Paul Dickson’s A Thoroughly Canadian General (2007), and a new study by John Rickard on General A.G.L. McNaughton entitled The Politics of Command.. There are good memoirs by Maurice Pope and E.L.M. Burns, for example, and a few horrors, such as that of Christopher Vokes. But other than Douglas Delaney’s The Soldier’s General (2005) on Bert Hoffmeister of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division, there are no first-rate new published studies of other Canadian commanders. We could do with books on brigade, battalion, company, and platoon commanders as well. There are no studies at all on senior air officers, and none on the Royal Canadian Navy’s leaders. Even with a population of just 11 million, Canada was, in some ways, the fourth greatest power in the greatest European war in history and, 65 years after the war ended that is all we have? This is an amazing state of affairs. We need biographies of the country’s key military, air, and naval leaders - a fully researched book on Guy Simonds, biographies of Charles Foulkes, Ken Stuart, Percy Nelles, Gus Edwards (or, at least, one not by his daughter), and ‘Black Mike’ McEwen of No. 6 (RCAF) Group in Bomber Command. The edited volumes organized by Richard Gimblett, Michael Whitby, and Jim Bouthilier and others on the RCN and its leaders are a very good start - we desperately need something like that for RCAF commanders - but scholars of the war need researched book-length biographies much more than edited collections.

Commander Charles Anthony Francis Law, Canadian Tribal Destroyers in Action, CWM 19710261-4057, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

Canadian Tribal Destroyers in Action, by Charles Anthony Francis Law, 1946.

I believe we need to stop the soft commemorations of anniversaries (in which Parks Canada, Veterans Affairs Canada, and others wallow) and cease ‘playing cheerleader’ for every aspect of Canada’s military efforts. I admit that I have done as much of this as anyone - and perhaps more. Why can more historians not deal with the failures of First Canadian Army openly and honestly as Jack English did, and now Yves Tremblay’s Instruire une armée: les officiers canadiens et la guerre moderne, 1919-1944 (2007) does? Why can we not begin to treat Canadian failings as honestly as British and American scholars do theirs? Max Hastings, in the New York Review of Books on 13 August 2009 (“A Very Chilly Victory”) wrote that the British Army “…disgraced itself for the first three years of the war, and seldom thereafter surpassed adequacy.” Hastings was right and was also correct when he pointed to the US Army’s weaknesses. It and the British did only enough “…to make a respectable subordinate contribution to the destruction of Nazism,” he wrote, while the Red Army ‘did the heavy lifting.’ At the very least, Hastings is being brutally honest in expressing his views of the British and American forces. Can Canadians not do the same?

Why can scholars - and museums - not talk about the RCAF part in the bombing campaign openly, and without fear of denunciation? The Valour and the Horror TV series of fifteen years ago was dreadful - but at least the McKenna brothers raised hard critical questions, if in an appalling, ignorant, ‘presentist’ way. But their questions, if only they had been stripped of bias and spin, were good ones. Historians need to bring a critical perspective to every aspect of the war. Essentially, the spectrum of comment must widen from its present focus on the “good war” to a more realistic approach that encompasses good and bad, success and failure. Jeff Keshen’s book, mentioned earlier, consciously set out to examine unsparingly “the good war” thesis - although in the ‘unkindest cut of all’ from one of my own PhD students, he used me as his target. Let us look at why Canada went to war, how Ottawa ran and fought it, and what the nation did right and wrong, without worrying about ‘exposing all the warts.’ There are relatively few warts - we have flogged Canadian sins about the forcible evacuation (not internment) of Japanese Canadians enough to make up for all the others - but it would do us good to be open and honest - and modest. It would also be very helpful if someone emulated Jonathan Vance’s fine Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War (1997) by looking at the memory and remembrance of the Second World War in Canada more than 70 years after its outbreak. We might also ask what impact - I think it was significant - the massive TV and print coverage of the 50th and 60th anniversaries of D-Day and V-E Day had upon the rejuvenation of military history, and upon the public memory of the war.

So, what does the history of Canada’s Second World War now demand? More. More of everything. But above all, we need gifted story-tellers writing big histories that are based upon hard research and rigorous ‘number-crunching.’ We need to re-envisage the present narrative of Canada and the war in a way similar to the fashions in which American historians regularly re-examine - and broaden the discussion upon - their Civil War. We do not want to abandon guns and trumpets, but we do need to go beyond them to take into account everything that the social and cultural approaches can offer.

Above all, military historians need to ensure that big syntheses get written. After 40 years of dominance by social and cultural historians in Canada, there is not a single major book that synthesizes those approaches and offers a full assessment of their impact upon Canada’s history.

Students of the Second World War cannot make the same mistake of focusing upon the particular or the trivial, or of producing endless edited books of essays that too often add very little except padding for Curriculum Vitae, when what we need are serious books by first-rate historians who will write hard-researched examinations of the truly important issues.

Major Charles Fraser Comfort, Dieppe Raid, CWM 19710261-2183, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum.

Dieppe Raid, by Charles Fraser Comfort, 1946.

![]()

Jack Granatstein, OC, PhD, one of Canada’s most renowned historians, has written extensively on Canada and the Second World War. He was Director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum from 1998 to 2000.