Main Heading of Page (h1)

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Valour (Vol. 11, No. 4)

Military History

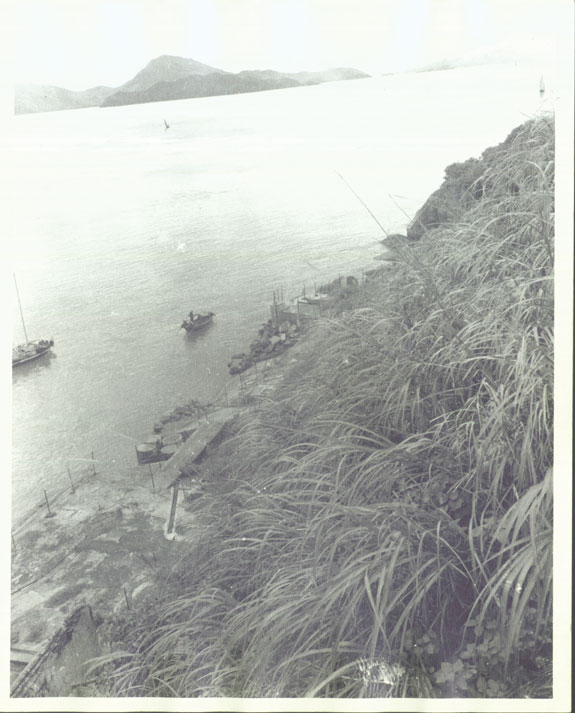

LAC/PA-166999

“C” Company of the Royal Rifles en route to Hong Kong, 15 November 1941, aboard HMCS Prince Robert.

Defeat Still Cries Aloud for Explanation: Explaining C Force’s Dispatch to Hong Kong

by Galen Roger Perras

Galen Perras, PhD, is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Ottawa. A Member of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies, his fields of interest include 20th Century American military and diplomatic history, Canadian-American relations, international relations in the Pacific world in the 20th Century, and Commonwealth military relations.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Background

In 1992, when I expostulated on the historiography of Hong Kong’s loss in 1941, I concluded we needed a good book that eschewed nationalist grudges.1 Nathan M. Greenfield’s 2010 monograph, The Damned: The Canadians at the Battle of Hong Kong and the POW Experience 1941-45, a ’popular account,’ has tried, and has received positive reviews.2 But Greenfield wrongly asserted C Force’s story is “little known,”3 and did not cite British documents and revisionist Canadian studies that put Hong Kong’s reinforcement in a strategic context. The book’s strength, a moving depiction of the pain C Force members endured in battle and in Japanese POW camps, is problematic as well. By emphasizing this narrative of suffering, Greenfield has perpetuated the notion that C Force’s sacrifices were the tragic product of colonial subservience. For this reason, and more, we still need a monograph that avoids nationalist ‘finger-pointing and grudge settling,’ is interpretatively innovating, and mines multinational archival sources.

Three ’official’ publications initiated the debate. Prime Minister W.L.M. King formed a Royal Commission in 1942, which absolved his government of responsibility as Supreme Court Chief Justice Lyman P. Duff accepted claims by General Harry Crerar and Minister of Defence J.L. Ralston that Canada had to respond to Britain’s September 1941 request for help at Hong Kong, as war with Japan did not appear imminent. The army was castigated for failing to deliver vehicles to the colony, and for dispatching 120 under-trained C Force members, although Duff ruled these failings had not seriously impaired C Force’s effectiveness.4 Although Conservatives labeled Duff’s report a whitewash, discord faded until 1948, when Major-General C.M. Matlby’s report about Hong Kong’s fall became public. Written in 1945, the document was edited after Canada insisted that Hong Kong’s fate “… would not have been changed to any appreciable extent” had C Force equaled the standard of units fighting in 1944.5 Still, the revised version asserted that the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been “inadequately trained for modern war,” and that Hong Kong’s defence was “a worth-while gamble.” King wanted to reveal secret documents that would demonstrate why London and Ottawa had buttressed Hong Kong in 1941. When London declined, King was castigated by Canada’s pro-imperial Conservatives for appealing to “his master’s London voice.” Moreover, The Globe and Mail opined that as Britain had not asked King before releasing Maltby’s report, King did not need Britain’s approval. By ‘hiding behind British skirts,’ The Globe accused King of taking a “mighty leap from nationhood to colonialism.”6

DND photo CFJIC ZK-703

General H.D.G. Crerar (left) and Lieutenant-General E.L.M. Burns in Italy, 1944.

Politics also affected C.P. Stacey, the Canadian Army’s official historian. As his 1983 memoir recounted, explaining Hong Kong was Stacey’s toughest historical task, due to a dearth of battlefield documentation, the death of C Force commanders, and powerful personages safeguarding reputations. An “embarrassed” Stacey had demanded Maltby’s report be amended, as Maltby, ‘fiddling the facts,’ had “put an undue share of the blame” on C Force. Stacey’s 1948 preliminary account echoed that Ottawa did not believe war was imminent, but did not mention that Major-General A.E. Grasett, Hong Kong’s former Canadian-born chief, had told Crerar and Britain’s Chiefs of Staff in August-September 1941 the colony could be made more defendable. Stacey also did not say Britain’s Chiefs in August 1940 had ruled Hong Kong was an outpost that could not be relieved and should not be reinforced. Instead, he cited Winston Churchill’s admission that having rejected plans to reinforce Hong Kong in February 1941, Churchill “allowed himself to be drawn from this position.”7

Volume One of the Army’s official history, published in 1955, created the mild nationalist critique that predominated in Canada for 25 years. Stacey adopted a tougher tone, perhaps, as he told a British historian, Canadians who survived Hong Kong “… assert, pretty universally,” that Maltby and Brigadier Cedric Wallis, “… being in search of scapegoats for the failure of the defence, fixed upon the Canadian battalions for this purpose.” As Canada, relying upon British intelligence, believed London’s claim that a small reinforcement could deter war, Churchill’s reversal “… would seem to have been one of those cases where second thoughts are not best.” More pointedly, it was an “egregious absurdity” to believe that two Canadian battalions would deter Japan. Mentioning Grasett, Stacey did not say Crerar had welcomed a request to reinforce Hong Kong, a scenario Crerar had denied to Chief Justice Duff. Maltby’s splitting of C Force had been “a serious disadvantage,” as the Royal Rifles had little confidence in Wallis, while C Force commander, Brigadier J.K. Lawson, unimpressed by garrison’s capabilities, had asked Ottawa for a third battalion.8 Stacey had ‘pulled some punches,’ noting: “… my view is that, particularly in the light of the rather fortunate fact that many of the controversies [over battle worthiness] have not reached the press, there is no point in raising these matters in print more than we have to.”9 Still, Stacey and official historians, with exclusive access to documents, “provided the first foundational studies.”10

DND photo CWM 1970036-024

Further Studies

However, some downstream British pronouncements proved unsettling. In 1957, the official historian S. Woodburn Kirby postulated that Canada mistakenly believed Britain’s request for help meant Hong Kong’s outpost status had changed. Another official historian, J.M.A. Gwyer, maintained that Hong Kong had to be defended, although it was known, “… we could not press the defence beyond a certain point.”11 A 1960 book by British Army veteran Tim Carew dismissed Grasett’s opinion that Hong Kong could be held as “light-hearted facile optimism.”12 Carew scorned Lawson as an amateur soldier, as he had taught school between the wars, and said C Force, trained for perfunctory security details, lacked British “sturdy independence of spirit.”13 Bereft of footnotes or Canadian sources, Carew’s book had two themes; sympathy for the ‘poor bloody infantry,’ and disdain for stupidity in high places.

According to his posthumously-edited wartime diary, King had been reluctant to aid Hong Kong, lest it “later afford an argument for conscription,”14 but Minister of National Defence for Air C.G. Power, his son serving in the Royal Rifles, vociferously advocated sending C Force. King avowed it was a mistake “to rush things unduly,”15 and to let the military take on more than it “had any right to assume.”16 In 1961, journalist Ralph Allan slammed London’s request as an old practice that regarded Dominion forces as “toy automata.” Professor James Eayrs termed Britain’s strategic assessment in 1941 “… a woefully inadequate appraisal of the situation.” J.L. Granatstein, a former official historian, said Canada was “… led down the golden path by a willingness to accept British assessments of the situation.” Still, Duff’s findings “were the only ones possible under the circumstances,” for while C Force’s training deficiencies were obvious, war did not seem imminent and King could not have easily refused London’s request.17 For former military historian George Stanley, reinforcing Hong Kong was a political decision that “displayed a political naïveté beyond comprehension.” Donald Creighton, in a vitriolic book that assailed King for selling Canada out to America, maintained London had not kept Canada in the picture about Hong Kong, while its “request” for C Force amounted to an order.18

Excepting General Maurice Pope, who averred sending C Force was “a manly and courageous stand to take,”19 no Canadian writer challenged Stacey, an omission that rankled University of Alberta historian Kenneth Taylor. Opining official military histories, “more celebratory than heroic than definitive,” pasteurized, homogenized, and tidied up war, he accused academic historians of absorbing Stacey’s opinions as “sacred codas which must be left to gather dust in respectful silence.”20 Early revisionist results were modest. Official historians W.A.B. Douglas and Brereton Greenhous said King’s “customary political insight had deserted him,” thanks to his limited military knowledge, an excuse neither Crerar nor Ralston could claim.21 Journalist Ted Ferguson’s emotional 1980 book condemned Ottawa for not “fully realizing the enormity of the task awaiting those troops.”22

LAC C-049742

Troops of C Force en route to Sham Shul Po Barracks, Hong Kong, 16 November 1941.

Two books better met Taylor’s revisionist hopes. Using newly opened British and Canadian records, Oliver Lindsay claimed, in 1978, that while defeat was a foregone conclusion, Hong Kong required defence, as Sino-American resolve to confront Japan might have waned. Still, Canadian troops should not have taken part because an overly optimistic Grasett believed they might deter attack, while Crerar’s dispatch of under-trained men demonstrated a poor understanding of the situation’s urgency. Lindsay asserted that the Royal Rifles commander, Lieutenant-Colonel William Home, asked about a cease-fire as further resistance was futile, but Wallis told Home to fight or to leave the front line under a white flag.23

Grant Garneau stalwartly defended the Royal Rifles in 1980. Although not the best available, C Force troops were not “… without preparatory seasoning for the active service into which all ranks found themselves plunged within two months of departure.” Crerar’s reasoning the soldiers could fix deficiencies was retrospectively “faulty and naive,” but the historical record indicated “it must be realized that the possibility that the troops might be immediately involved in action was apparently never seriously considered.” Ottawa’s decision was made in “good faith,” yet Canadian authorities did not “calculate the risks involved nor were they willing to assume the responsibility when the loss of the force occurred.”24 Unhappy with local defences, Lawson wanted another battalion plus artillery and engineers, while the Rifles endured “an apparently inept British officer who was used to dealing with Indian troops and was incapable of comprehending vital aspects of the Canadian personality.” Although victory was impossible, more soldiers would have survived had Wallis not ordered needless counter-attacks that produced a 37 percent casualty rate and compelled Home’s demand, on 24 December, that his unit be relieved.25

DND photo LAC/PA-037419

Infantrymen of “C” Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, disembarking from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, 16 November 1941.

In No Reason Why: The Canadian Hong Kong Tragedy, Carl Vincent decried that C Force members were the only Commonwealth soldiers in the war to be “deliberately sent into a position where there was absolutely no hope of victory, evacuation, or relief.” This blunder would baffle future investigators, for “there was no reason why.”26 Grasett was the sole British actor to believe two battalions would help, thanks to his “contempt for Japanese military ability, a fixed determination to ‘put on a good show,’ and remarkably poor powers of military appreciation.” Grasett’s success stemmed from his claim the men would come from an untapped source, while Churchill had forgotten “the risk to the garrison or considered it worth taking.”27 The Dominions Office telegram of 19 September 1941 asking for soldiers had remarked British policy “has been” to see Hong Kong as an outpost, the present tense falsely implying a policy change. As Canada’s Ministers were busy men with “neither the knowledge nor the inclination to read between the lines or wonder about motivations,” an automatic ‘yes’ was in order, unless there were sound military reasons to say ‘no.’28 Reasons existed, but when Ministers sought his expert opinion, as Crerar claimed, “political and moral principles were involved, rather than military ones.” This explanation – equated to Pontius Pilate washing his hands twice – demonstrated Crerar had forgotten he was to advise his political masters, not usurp their jobs “… by failing to make it plain to the politicians that the military risks were very real.”29

Unwilling to divert formations slated for Britain, Crerar judged the Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles to be of proven efficiency. Vincent revealed that Major J.H. Price, the Rifles’ second-in-command, had asked Power, in September 1941, to get his unit attached to a larger body so that it could get advanced training. As Power responded that events overseas would “soon develop to the point where it will be possible for your lot to have the opportunity it deserves,” it could not be coincidental that Price’s unit joined C Force.30 After Japan’s landing on 18 December decimated the Royal Scottish and Rajput Regiments, and left the Middlesex and Punjab Regiments trapped in fixed positions, the combat burden fell upon the Rifles, who launched more company level counter-attacks than all imperial units combined, a standard the Grenadiers nearly matched. The Japanese suffered their heaviest losses in encounters with C Force.31 Vincent had contempt for Duff’s inquiry, but recognized an impartial Duff could not have questioned King’s war management, as that was Parliament’s task.32 Duff uncritically accepted senior officer testimony about C Force training standards from “men whose professional reputations would have been injured if their choice of these battalions had not been upheld.” Vincent put the number of untrained men at 250, while 20 percent of the Grenadiers and 40 percent of the Rifles had not passed elementary weapons tests.33 The transport issue, however, ensured Duff’s findings were a whitewash. While three witnesses on Vancouver’s docks in October 1941 testified vehicles could have accompanied the troops, Duff accepted contrary testimony from an official who had not been in Vancouver, and had overlooked reports about Hong Kong’s desperate transport shortage.34

Vincent’s Anglophobic book relied on just 14 files from Britain’s Public Record Office but none from key War Office, Foreign Office, Admiralty, or Cabinet record groups, an omission that injured his thin prewar explanation.35 Kenneth Taylor, in the Globe and Mail, attacked Vincent’s “emotional anti-Liberal and anti-Churchillian hysterics” and the implication C Force had fought for nothing. Who knows, Taylor claimed, how close Japan came to changing its plans in late 1941.36 But it took several years for academic historians to weigh in. In 1994, University of Calgary historian John Ferris said Vincent’s argument “is accepted by no reputable authority,” while Tony Banham, a Hong Kong-based author, dismissed No Reason Why as “damaged by a blatant nationalism that is painful to the non-Canadian (and hopefully, for most Canadians as well),” and for doing “little to advance our knowledge of the subject.”37 Yet, Canadian historian Gregory A. Johnson said Vincent’s “vitriolic” study “essentially created a new foundational myth about the Canadian experience at Hong Kong that was given wide currency more than a decade later,” when The Valour and the Horror, a controversial TV documentary, appeared.38

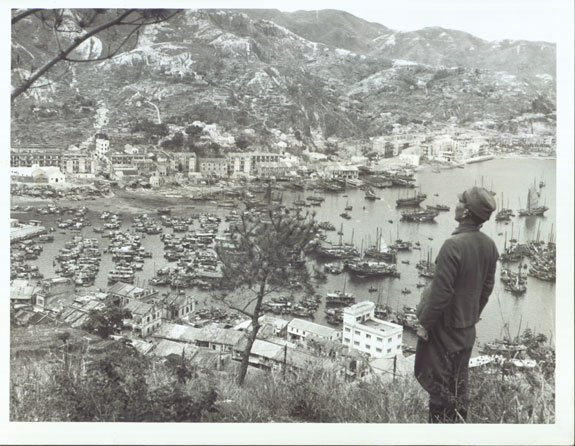

DND photo 17_08_2001-2

The spot where the Royal Rifles of Canada stood guard over Lemun Pass and repelled two attempts by the Japanese to land.

Brereton Greenhous, who countered that any competent military historian could attest there was “no evidence that Japanese plans were affected,” later called Vincent’s study “the best Canadian monograph on the subject.”39 When the Canadian Hong Kong Veterans Association campaigned in 1987 to compel Japan to compensate C Force survivors, it used No Reason Why, while the media cited Vincent.40 Stacey, savaged by Taylor and Vincent, oddly did not respond. His 1984 study of King’s foreign policy ’astonishingly’ did not mention Hong Kong once,41 perhaps Stacey believed, as he had stated in his last official history in 1970, Hong Kong’s “ill starred” story was “fully told elsewhere.”42 Granatstein said Vincent had failed “to understand the political realities” pertaining in 1941, a critique buried in an 2002 endnote.43

Two overlooked studies bettered our understanding. David Ricardo Williams’ 1984 biography of Duff revealed that King and Duff had ensured the government would escape censure.44 In 1989, Gregory A. Johnson produced a fine doctoral thesis, North Pacific Triangle? The Impact of the Far East on Canada and Its Relations with the United States and Great Britain, 1937-1948. Adroitly using Canadian, British, and American records, Johnson put Canada’s involvement in Pacific affairs in proper context, and refined King’s role. Fearful pro-imperialists would pounce, King “was forced to let Canada stand, once again, at Britain’s side.” Further, in a hidden diary entry, King had written “For Canada to have troops in the Orient, fighting the battle of freedom, marks a new stage in our history. That, too, is a memorial”45 Contrast this entry to King’s false assertion in 1948 that he had opposed “strenuously sending troops to cross the Pacific Ocean” in 1941.46

In January 1992, The Valour and the Horror, the aforementioned docudrama by journalists Brian and Terence McKenna, shocked many. Given its claims that incompetent Canadian and British militaries had wasted Canadian lives, and that officials and historians had hidden this wrongdoing, Brian McKenna had thought “controversy” was probable.47 Despite winning national television awards, including best documentary, the CBC’s Ombudsman ruled, in late-1992, that the “flawed” series had not met network “policies and standards.”48 The McKennas failed to mollify critics as Brian, averring the issue was “about history and who gets to tell it,”49 labeled his research “bullet-proof,” and the Senate hearings a “smear job.”50 The McKennas argued the Ombudsman had not found “a single serious error in the entire six hours of television,” adding “our work is to be severely judged, not because of what we actually said, but because of the many other things Mr. Morgan and others wanted to hear that we did not say.”51

This sharp fight was about “ownership” of history, generational identity, freedom of speech, objectivity, interpretation, and dissent from dominant hegemonic viewpoints.52 Admitting the McKennas “had a right to their point of view,” senators wanted a disclaimer to say the series was “a docu-drama only partly based on fact,” asked the CBC to shelve the unamended series, and invited the National Film Board to produce a documentary that “redresses the imbalances and corrects the inaccuracies of The Valour and the Horror.”53 For Professor Michael Bliss, the anti-McKenna hostility was not “very Canadian.”54 When Granatstein asserted the “real issue” was about who “writes history,” and that television history will “have more impact on ...people who know nothing about the war than anything I write,” Bliss retorted Granatstein thought history “properly belongs to the historical profession.” Professor Terry Copp, targeting the baby boomer McKennas, declared there was “no worse present for viewing the past of the 1940s than to have been a university student and a young man in the sixties and early seventies.”55

DND photo 17_08_2001-01.

Sau Ki Wan, where the Tanaka Butai landed on the night of 18-19 December 1941. The person in the foreground is General Tanaka himself, 19 March 1947, taken just prior to his war crimes trial.

DND Map HK 462e

The third installment, Savage Christmas, centered upon two Canadian veterans revisiting Hong Kong and Japan. An encounter between one Canadian and Japanese veterans from Hong Kong was riveting, as the Japanese froze when they found out the absent Canadian, a witness to the murder of prisoners at Hong Kong, refused to meet them. But a lack of vital context about Hong Kong’s strategic situation and pervasive anti-British bias distorted the show. Further, asserting British and Canadian officials “knowingly” sent C Force to its doom was so preposterous even Vincent would not use the word “knowingly,” when asked by the Ombudsman.56

For David Bercuson, co-editor of a 1994 book about The Valour and the Horror:

”The clear impression presented is that Canada, as Britain’s lap-dog, either deliberately and knowingly sent its young men, untrained for war, to slaughter to stay in Britain’s good graces, or should have known that they were being sent to the slaughter. This is pure fiction. Thus, although much of the film presents a balanced view of the Hong Kong battle and its aftermath, the central theme is developed without regard to a readily available mountain of evidence that that theme is a figment of the imagination of the producers. No part of that mountain of evidence which runs counter to this theme is presented to the viewer.”57

John Ferris, an intelligence expert, was no kinder.

Indeed, except for three minutes of a 104-minute presentation, Savage Christmas showed nothing to which any reasonable person could object. However, it is precisely those three minutes that contain two of the most controversial allegations made by the program producers. There, the McKennas present their interpretation of why Canadians were sent to Hong Kong in the first place, criticize the Canadian government for doing what it did, and assert that the dispatch of essentially untrained-for-war soldiers was a monstrous act.58

Claims British commanders knew war was “inevitable and imminent,” yet misled Canada or that Ottawa “knowingly” sent troops “lambs to the slaughter” because it “offered an opportunity to wave the flag” were unsupported. If British officials misjudged Japan’s intentions or Hong Kong’s defensive capacity, “this makes them fools, but not villains. They did not consciously risk Canadian instead of British lives for the sake of prestige. They did not deliberately sacrifice Canadian troops.”59 As Ferris noted:

If one must find villains behind the Hong Kong debacle, one need merely look in the mirror. The guilty men were a Canadian society and government that starved its military forces for years on end and then one day sent them off against well-equipped enemies, in pursuit not of national interests defined by Canadian politicians but of international interests defined by external authorities. Hong Kong was not the first example of the phenomena or the last. It happened in the First and Second World Wars, in the Korean War and in the Gulf Conflict. The risk was taken in NATO and everywhere Canadians have served as UN peacekeepers. It is the Canadian way of war.60

The Valour and the Horror had a catalytic impact. In January 1993, Britain’s Cabinet, irked by Canadian accusations of British perfidiousness, and Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating’s public denunciation in 1992 of Britain’s failure to hold Singapore in 1942, a catastrophe that had enveloped 20,000 Australians, acted. It unlocked Matlby’s unedited report and the Wavell Report on Singapore, which claimed cowardly and mutinous Australians had doomed Singapore, revelations that received prominent press coverage in Britain and Hong Kong.61 The Calgary Herald called Maltby a lying strategic bungler, Vincent told The Edmonton Journal that Canadians were “convenient scapegoats” for “the early fall of Hong Kong,” and The Vancouver Sun termed C Force’s dispatch “a suicide mission.” C Force veteran Sid Vale called British troops “cowards” who hid “back at the hotel,” while Canadians fought. Globe and Mail columnist Michael Valpy charged it was “a toss-up who posed the greater threat to [Canadian troops] – the British and Canadian generals and politicians who sent them, or the Japanese.”62

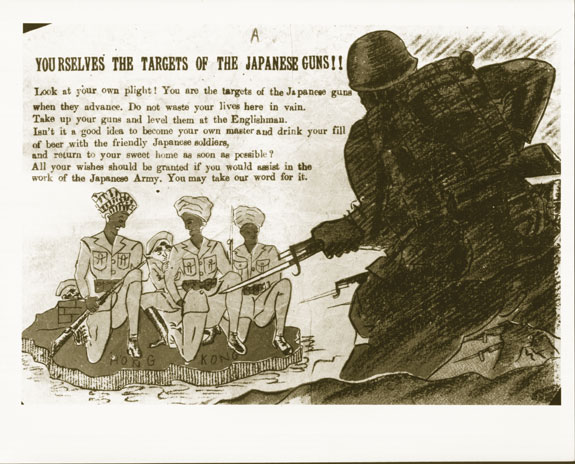

DND photos 17_08_2001-04 and 17_08_2001_05 respectively. (top to bottom)

Two Japanese propaganda leaflets, in this case, directed against Commonwealth troops from India.

The series also prompted Canadian historical revisionism. As Crerar had studied Hong Kong at the Imperial Defence College (IDC) in the 1930s, Paul Dickson contended the general’s decisions derived from “a reasoned analysis of the contemporary strategic situation in the Far East, his long-term objectives for the army, and the reality of the state of the army’s training,” plus a belief that Japan would lose any war as America would join Britain. Still, “Crerar should be faulted for his failure to make the potential risks inherent in garrisoning Hong Kong absolutely clear to the government. That was his responsibility.”63 Two articles by myself and Christopher M. Bell, which mined British records, made two key arguments: a longstanding debate existed with respect to Hong Kong’s defences; and Hong Kong’s reinforcement must be seen as part of a broad Western attempt to deter war by buttressing the Asia-Pacific bases. As Bell noted: “The nature of the debate over Hong Kong’s defence during the pivotal period 1934-38 has been widely misunderstood. That Hong Kong would be difficult to defend was apparent, but it was not always judged to be impossible.” Local commanders underestimated the likelihood of Japanese attack, and overrated defensive prospects, while London was more confident war could be averted, or that American support would be forthcoming.64

Such welcome revisionism was absent in Greenhous’ 1997 book, “C” Force to Hong Kong”: A Canadian Catastrophe, 1941-1945. For a work that Banham nicknamed “Maltby’s Great Mistakes,”65 Greenhous relied upon C Force veteran accounts and a small number of files located in Ottawa. He slammed Crerar as “a ruthless and studiously and ambitious sycophant,” whose assertion that Grasett did not ask for help should be doubted, although the general may have spoken “obliquely.” The Dominions Office was “perfidious Albion,” Maltby a crude caricature, and Stacey had not blamed Crerar because he “had been a Crerar protégé since 1940, and he owed his appointment as official historian to Crerar, who was still alive at the time.”66

While the Oxford Companion of Canadian Military History listed only Greenhous’ book as recommended reading with respect to Hong Kong,67 Greenhous could not stem revisionism. Terry Copp, having argued in 1996 that “there was a reason” for C Force’s dispatch – Canada had sought, with its allies, “for the best of reasons,” to strengthen Hong Kong to “defer or deter war”68 – dedicated the Autumn 2001 edition of Canadian Military History to C Force. Copp alleged that this story of sacrifice had been forgotten, “because, we are told, they fought in a hopeless cause and should not have been there in the first place.” Canadians had to “free ourselves from the distorted sense of hindsight” to comprehend C Force’s fate.69 C Force had been badly served by a Canadian government, whose cheapness had left troops “grievously handicapped by their lack of training, poor equipment and shortages of ammunition.” Further, Churchill had sacrificed “British and Commonwealth forces in the Far East rather than jeopardize hopes of a major victory in North Africa.”70

Granatstein’s views hardened. In 1993, he termed Grasett’s mannerisms “… almost a caricature of those of the British upper classes,” while Crerar escaped censure “as he almost always did.” His 2002 history of Canada’s army bluntly stated that Canada’s Cabinet had been “snookered” by Britain’s aid request. That C Force’s vehicles did not arrive was a “catastrophe,” while Maltby’s choice to leave the vital high ground to the Japanese was curious. In 1941, Canada’s army was not efficient administratively, and Ottawa lacked an “ability to determine if troops should be committed to operations. In effect, Canada needed to act like a nation, not a colony.”71 Then, in Who Killed Canadian History?, averring Canada’s historical meta-narrative was threatened by touters of class, gender, and race, Jack Granatstein condemned the McKennas, who “tried to be ‘fair’ to the Nazis, and alleged that “generals and officers strive for personal glory as they threw away their troops at Hong Kong and in futile attacks in Normandy.”72

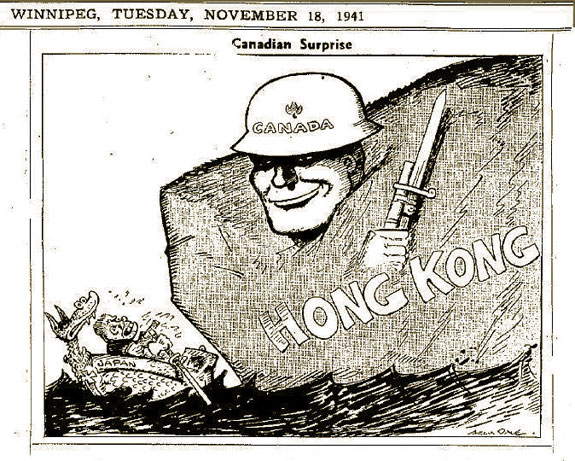

Winnipeg Free Press/cartoonist Archie Dale

Winnipeg Free Press political cartoon of the Canadian deployment to Hong Kong, November 1941. Unwarranted optimism, as it transpired.

Three works were notable for different reasons. Despite his difficulties accessing Canadian, British, and Japanese records in the 1950s, Tim Cook maintained that a constrained Stacey kept to “a middle course” by not blaming any general or politician for C Force’s deployment.73 Tony Banham’s Not the Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong, 1941, painstakingly chronicled Hong Kong’s siege. Condemning Vincent, Greenhous, and The Valour and the Horror, Banham called Ferguson’s effort “one of the best balanced books to come from Canadian sources,” and said Garneau’s “scholarly” monograph was a “must for anyone seriously studying East Brigade or the battle as a whole.”74 Kent Fedorowich’s 2003 article, which credited The Valour and the Horror for rekindling debate, postulated that debate was injured by three tendencies; viewing Hong Kong as an adjunct of Singapore’s loss; compartmentalizing military and political aspects at the expense of the diplomatic canvas in Asia; and ‘trotting out’ the highly charged claim that Britain had sacrificed Canadians. Fedorowich set Hong Kong’s reinforcement in a complex temporal and thematic framework, although he admitted, “the Hong Kong controversy is far from settled.” Britain badly needed to retain Hong Kong to prevent China from making peace with Japan, while Canada “badly wanted to demonstrate to the Canadian public, its Commonwealth partners, and especially its southern neighbour, that its war effort consisted of more than just wheat, warships, and fixed-wing aircraft.” To say Canada was ‘led down a garden path’ at Hong Kong “… by having to rely on British assessments is superficial and inaccurate. Ottawa had travelled well down that path already.”75

This brings us again to Greenfield’s book. Greenfield clearly saw himself, like Vincent, as an advocate for C Force’s members. Explaining that he was the first author to use the Japanese official history and Japanese memoirs, he could not “divide morality in half,” as that “would verge on blasphemy.” And while he argued that some of Wallis’ East Brigade Diary “was indeed correct,” taken as a whole, it was a “calumny.”76 Although Greenfield’s bibliography was large, most sources, including Bell and Fedorowich, were not found in any endnotes, while half the endnotes in the introduction came from No Reason Why. Advocacy is not necessarily good history.

Why has this small episode from a vast conflagration that killed 60 million people sparked such vehement debate? Canada suffered five times more casualties taking Vimy Ridge in 1917, but Vimy may have arguably ‘created’ modern Canada. Over 10,000 Canadians died in Bomber Command in the Second World War. And yet, excepting the McKenna’s episode with respect to bombing, a brief contretemps at Canada’s War Museum about wording on its bomber offensive panel, and vet concerns about how the Air Force official history portrayed that offensive as murderous, costly and ineffective,77 Canada is not awash in dueling air power critiques and defences. However, as Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan astutely noted, “… defeat cries aloud for explanation; whereas success, like charity, covers a multitude of sins.”78 Both the massive compendium of historical literature dealing with America’s Pearl Harbor defeat, and Australia’s ongoing obsession with respect to Singapore’s fall, illustrate that recrimination about battles lost is not exclusively a Canadian preoccupation.79 Hong Kong provides much to discuss, with allegations of incompetence, political misconduct, ‘buck-passing,’ and colonial subservience. David Ricardo Williams offered another explanation. Hong Kong marked the first time Canada dispatched soldiers to the Orient “… and it may be that the sense of strangeness and the unfamiliar ground keeps this concern alive.”80

Canada’s army suffered two great defeats during the Second World War, at Hong Kong, and at Dieppe in August 1942, where the Second Division took 3400 casualties, including 907 dead. Dieppe has produced a contentious historiography, notably Brian Loring Villa’s 1991 book that alleged Lord Mountbatten, the head of Combined Operations in Britain, launched the raid without authorization.81 Terry Copp, while praising Villa as “… a serious historian who has invested years of archival research,” did not accept Villa’s thesis,82 but that contentious debate remained civil. Perhaps Dieppe’s dreadful casualty list has been made more tolerable, as Allied leaders argued lessons learned there paved the way for D-Day in 1944,83 or perhaps the disparate fate of the two groups of Canadian POWs matters. Seventy-two of the 1946 Canadians taken prisoner at Dieppe died in German camps, a death rate of four percent. However, 281 C Force members died in captivity, a 17 percent fatality rate.84

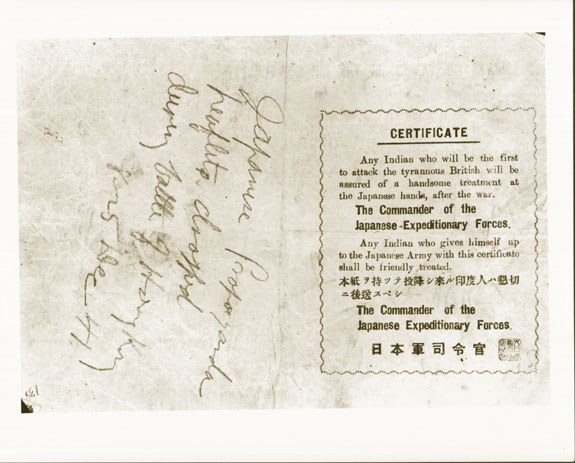

DND photo 17_08_2001_3.

Canadians en route to Hong Kong aboard HMCS Prince Robert. Note the smiles.

Conclusions

What we now possess is a collection of works of varying length and quality, none of which has combined all of the aspects of this topic – political and military, domestic and international – into an integrated, comprehensive statement. It is all too easy to say that Grasett’s view that a modestly-reinforced garrison could resist a Japanese assault swayed Britain’s Chiefs, or Churchill himself. We need to better understand Churchill’s role in this event. Was Grasett’s case so convincing, was Churchill’s judgment so bad, or was he far more concerned with reassuring allies that Britain would defend its profitable Asian possessions? Few have delved deeply into Grasett’s role. While he acted determinedly to bolster his former command in late- 1941, such energy, Lindsay claimed, would have surprised former subordinates, as Grasett had done little to secure Hong Kong while in command.85 Fedorowich played up Grasett’s eloquence in making his case to British leaders in September 1941, especially as his optimistic claims fit an apparently-easing diplomatic situation at the time.86 But was it clever phrasing, or Grasett’s expertise that made the difference? And, despite Dickson’s defence, Crerar’s role needs greater examination. What did he know and not know about the Asian strategic situation when he told Canada’s Cabinet in the autumn of 1941 that sending C Force was a political, not a military decision? How did he escape censure in 1942?

Cooperation between the Canadian and British militaries prior to 1941 needs study. As Jack Granatstein noted, ten Canadian officers, including Crerar, studied at the IDC before 1939, examining various military-political scenarios, including Hong Kong.87 We know little about how Canadian officers viewed the IDC, their imperial classmates and instructors, or how they incorporated global imperial defence concepts into Canadian mind-sets. We must expand upon Norman Hillmer’s 1978 article about cooperation between Canadian and British officers prior to 1939.88 Most Canadian analysts have viewed C Force’s dispatch as a decision made solely for political reasons, without accounting for the concrete and emotional ties between Britain and Canada. If one ignores how such influences affected Canadian decision-makers in 1941, a vital part of the C Force story is missing.

‘Getting the story right’ might entail making one consider the subject in different ways, and using different sources. In 2008, Gregory A. Johnson cited some C Force veterans who doubted that they had been knowingly put at risk. Thanks to the presence of Power’s son and other boys from wealthy Quebec Anglophone families in their ranks, some thought the Rifles, the “million dollar regiment,” went to Hong Kong to keep it from combat in Europe.89 Lawrence Lai Wai-Chung’s 1999 paper compared the performance of Hong Kong’s garrison to British defeats at Crete and Malaya/Singapore. Although Hong Kong’s defenders had been outnumbered three-to-one, Crete’s garrison had enjoyed a two-to-one advantage over the attacking Germans, while Malaya’s imperial forces outnumbered the Japanese three-to-one. Hong Kong’s defenders lasted 18 days and suffered twice as many fatal casualties – 2.11-to-1 – as the Japanese. At Crete, Allied forces suffered more than twice as many dead as the Germans, 2.39-to-1, in 11 days. Only at Singapore did the British lose fewer men – 0.73-to-1 – but 120,000 Allied troops surrendered there. After weighing the relative loss rates of Allied defenders against the relative strength of invaders to defenders, Allied loss rates were 4.6 percent at Crete, 1.74 percent for Malaya/Singapore, and just 0.68 percent at Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s garrison, “… however unprepared and poorly equipped, had fought quite well,” thanks to rugged topography, the fact that the garrison “… fought in an orderly manner according to a pre-conceived plan with defence structures well in place,” Japan’s failure to destroy British forces withdrawing from the mainland, and many machine guns and artillery pieces of various kinds equipping the defenders.90 Robert Ward, America’s Consul in Hong Kong when the colony fell, offered an explanation for the defeat. Doubting Japan had employed more than 12,000 troops against 9000 imperial regulars and 3000 volunteers, Ward stated that the defenders possessed essential provisions to withstand a six-month siege. Instead, the garrison surrendered after just 18 days, as a complacent local British community had not psychologically prepared itself or the Chinese populace for war. British leadership in Hong Kong was so intent upon not destroying a colony that it hoped to get back at war’s end that it declined to practice a scorched earth policy, and its defeatism “… reached up to the Governor and down to the men.”91

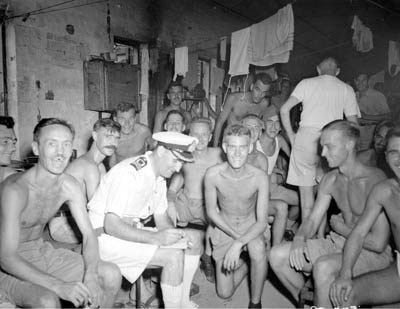

LAC/PA-145983.

Canadian and British prisoners-of-war liberated by the boarding party from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, August 1945. Again, note the smiles.

Finally, we must discard the assumption that aiding Hong Kong was a bad moral choice. Dispatching C Force was a poor decision retrospectively as it only added to the magnitude of the defeat. But bad strategic choices are inevitable in war’s dense fog, as few leaders possess all the facts. Nor can they discard easily deeply-held assumptions and preconceptions with respect to themselves, their allies, and their foes, especially when there is a perceived or real need to reach conclusions quickly. And yet, a bad decision is not necessarily an immoral decision. The choice to reinforce Hong Kong has acquired such a taint, thanks to distasteful political manoeuvres, prisoner of war (POW) sufferings, and nationalist ‘finger-pointing.’ Overcoming the dominant narrative of suffering will be difficult, as we have been conditioned to fear that manipulative decision-makers can avoid ramifications of their bad decisions, while their ’victims’ bear the terrible consequences. Another academic history may not satisfy everyone. As a journalist had stated in 1994 during the McKenna contretemps, one is only “… permitted to speak about great events in world history if you are a dean at an approved university.”92 It needs to be done, and the Canadian revisionists’ pieces provide the base upon which to build a study that will critically examine the complicated prewar context, the battle itself, and the political and historical battles that have yet to abate.

NOTES

-

Galen Roger Perras, “‘Defeat Cries Aloud For Explanation’: An Examination of the Historical Literature on the Battle of Hong Kong,” Canada and the Second World War in the Pacific Conference, Victoria, BC, 27-29 February 1992.

-

J.L. Granatstein, “A Dieppe in the Far East,” in The Globe and Mail, 6 November 2010; and Jim Blanchard, “Ottawa historian honours Battle of Hong Kong vets,” in The Winnipeg Free Press, 16 October 2010.

-

Nathan M. Greenfield, The Damned: The Canadians at the Battle of Hong Kong & the POW Experience 1941-45 (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2010), p. xxv.

-

Lyman P. Duff, Report on the Canadian Expeditionary Force to the Crown Colony of Hong Kong (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1942), pp. 3-9.

-

Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes to Minister of National Defence, 9 February 1948, Kardex file 111.13 (D66), Directorate of History & Heritage, Department of National Defence, Ottawa.

-

Major-General C.M. Maltby, Operations in Hong Kong from 8th to 25th December, 1941, in Supplement to the London Gazette of 27 January 1948; “Mr. King waits reply from ‘his master’s London voice’ to release Drew letter,” The Globe and Mail, 7 February 1948; and “From Nation to Colony,” in The Globe and Mail, 2 February 1948.

-

C.P. Stacey, The Canadian Army 1939-1945: An Official Historical Summary (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1948), pp. 289-304; and Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War,Vol. III: The Grand Alliance (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), p. 177.

-

Stacey to J.R.M. Butler, 13 March 1953, RG25, Volume 12753, File 308/10, Library and Archives Canada; and C.P. Stacey, Six Years of War: The Army in Canada, Britain and the Pacific (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1955), pp. 439-443.

-

Stacey to Butler, 13 March 1953, Cabinet Office, Historical Section, War Histories, CAB101/153, TNA.

-

Tim Cook, Clio’s Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006), p. 6.

-

S. Woodburn Kirby, The War Against Japan. Volume One: The Loss of Singapore (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1957), pp. 81-82; and J.M.A. Gwyer, Grand Strategy: Volume III: June 1941-August 1942, Part One (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1964), p. 311.

-

Tim Carew, The Fall of Hong Kong: The Lasting Honour of a Desperate Resistance (London: A. Blond, 1960), pp. 11, 28, & 134.

-

J.W. Pickersgill, (ed.), The Mackenzie King Record, I: 1939-1944 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1960).

-

Ralph Allan, Ordeal by Fire: Canada, 1940-1945 (Toronto: Doubleday, 1961), p. 396; James Eayrs, The Art of the Possible: Government and Foreign Policy in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961), p. 139; and J.L. Granatstein, Conscription in the Second World War 1939-1945: A Study in Political Management (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1969), pp. 50-51.

-

George F.G. Stanley, Canada’s Soldiers: The Military History of an Unmilitary People (Toronto: Macmillan, 1974), pp. 380-381; and Donald Creighton, The Forked Road: Canada 1939-1957 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1976), p. 61.

-

Maurice A. Pope, Soldiers and Politicians: The Memoirs of Lt. General Maurice A. Pope (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962), p. 173.

-

Kenneth Taylor, “The Challenge of the Eighties: World War II from a New Perspective – The Hong Kong Case,” in Timothy Travers and Christon Archer, (eds.), Men at War: Politics, Technology and Innovation in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: Precedent, 1982), p. 201.

-

W.A.B. Douglas and Brereton Greenhous, Out of the Shadows: Canada in the Second World War (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1977), pp. 105-106.

-

Ted Ferguson, Desperate Siege: The Battle of Hong Kong (Toronto: 1981), p. 7.

-

Oliver Lindsay, The Lasting Honour: The Fall of Hong Kong, 1941 (London, 1978), pp. 111, 114, 147-148, and 197-200.

-

Grant S. Garneau, The Royal Rifles of Canada in Hong Kong - 1941-1945 (Sherbrooke, QC: Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association, 1980), pp. 12-13 & 148.

-

Carl Vincent, No Reason Why: The Canadian Hong Kong Tragedy – An Examination (Stittsville, ON: Canada’s Wings, 1981), pp. 35 & 249.

-

K.C. Taylor, letter to the editor, in The Globe and Mail, 1 March 1982.

-

John Ferris, “Savage Christmas: The Canadians at Hong Kong,” in David J. Bercuson and S.F. Wise, (eds.), The Valour and the Horror Revisted (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), p. 112; and Tony Banham, Not the Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong, 1941 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003), p. 396.

-

Gregory A. Johnson, “The Canadian Experience of the Pacific War: Betrayal and Forgotten Captivity,” in Karl Hack and Kevin Blackburn, (eds.), Forgotten Captives in Japanese-Occupied Asia (London: Routledge, 2008), p. 128.

-

Brereton Greenhous, letter to the editor, The Globe and Mail, 9 March 1982; and Brereton Greenhous, “C” Force to Hong Kong: A Canadian Catastrophe, 1941-1945 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1997), p. 19.

-

Brian N. Forbes and H. Clifford Chadderton, Compensation to Canadian Hong Kong Prisoners of War by the Government of Japan, Submission to the United Nations Commission of Human Rights, ECOSOC Resolution 1503, May 1987; and Terry Johnson et al., “The Forgotten WWII Heroes,” Western Report, 31 August 1987.

-

C.P. Stacey, Canada and the Age of Conflict. Volume 2: 1921-1948: The Mackenzie King Era (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984); and Johnson, p. 130.

-

C.P. Stacey, Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada 1939-1945 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1970), p. 156.

-

J.L. Granatstein, Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), p. 451, n 63.

-

David Ricardo Williams, Duff: A Life in the Law (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1984), pp. 223-235.

-

Gregory A. Johnson, North Pacific Triangle? The Impact of the Far East on Canada and Its Relations with the United States and Great Britain, 1937-1948, PhD thesis, York University, 1989, p. 202. One historian speculated King hid the entry because he had anticipated “fallout to the decision” to dispatch C Force; John D. Meehan, The Dominion and the Rising Sun: Canada Encounters Japan, 1929-1941 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004), p. 192.

-

Diary entry, 25 February 1948, King Papers, Library and Archives Canada.

-

Graham Carr, “Rules of Engagement: Public History and the Drama of Legitimation,” in Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 86 (June 2005), p. 318.

-

William Morgan, “Report of the Ombudsman,” 6 November 1992, in Bercuson and Wise, pp. 61-72.

-

John Ward, “Panned War Film Called Bullet-Proof,” in The Vancouver Sun, 26 June 1992.

-

Brian and Terence McKenna, “Response to the CBC Ombudsman Report,” in Bercuson and Wise, pp. 80-81.

-

Carr, “Rules of Engagement,” passim; and David Taras, “The Struggle Over ‘The Valour and the Horror’: Media Power and the Portrayal of War,” in The Canadian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 28 (December 1995), pp. 725-748.

-

Granatstein and Bliss, cited in Carr, pp. 323-324; and Terry Copp, cited in Graham Carr, “War, History and the Education of (Canadian) Memory,” in Katharine Hodgkin and Susannah Radstone, (eds.), Contested Paths: The Politics of Memory (London: Routledge, 2003), p. 59.

-

David J. Bercuson, “The Valour and the Horror: An Historical Analysis,” in Bercuson and Wise, p. 38.

-

John Crossland, “Canadians branded cowards in Hong Kong battle,” in The Sunday Times, 31 January 1993; and John Crossland, “Canadian Courage and Cowardice?,” in South China Morning Post, 1 February 1993. Keating’s criticism buttressed Australian republicanism; James Curran, “The ‘Thin Dividing Line’: Prime Ministers and the Problem of Australian Nationalism, 1972-1996,” in Australian Journal of Politics and History, Vol. 48 (No. 4, 2002), p. 483.

-

“Dead General Lied,” in The Calgary Herald, 2 February 1993; “Hong Kong, Canadians and the Charge of ‘Cowardice’,” in The Edmonton Journal, 2 February 1993; “Canadian Troops Were Doomed As Soon As They Landed,” in The Vancouver Sun, 5 February 1993; Sid Vale cited in “Hong Kong Vets Stung By Charge of Cowardice,” in The Edmonton Journal, 2 February 1993; and Michael Valpy, “Why the Canadians Were in Hong Kong in 1941,” in The Globe and Mail, 3 February 1993.

-

Paul Dickson, “Crerar and the Decision to Garrison Hong Kong,” in Canadian Military History, Vol. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 99-102 & 107.

-

Galen Roger Perras, “‘Our position in the Far East would be stronger without this unsatisfactory commitment’: Britain and the Reinforcement of Honk Kong, 1941,” in Canadian Journal of History, Vol. 30 (August 1995), pp. 232-259; and Christopher M. Bell, “‘Our most exposed outpost’: Hong Kong and British Far Eastern Strategy, 1921-1941,” in The Journal of Military History, 60 (January 1996), pp. 61 and 87.

-

J.L. Granatstein and Dean F. Oliver, The Oxford Companion of Canadian Military History (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 200-203.

-

Terry Copp, “Hong Kong: There Was a Reason,” in Legion Magazine (1 March 1996), online edition.

-

Terry Copp, “From the Editor,” in Canadian Military History, Vol. 10 (Autumn 2001), p. 3.

-

Terry Copp, “The Defence of Hong Kong December 1941,” in Canadian Military History, Vol. 10 (Autumn 2001), pp. 5, 7, & 17-19.

-

J.L. Granatstein, The Generals: The Canadian Army’s Senior Commanders in the Second World War (Toronto: Stoddart, 1993), pp. 98-99; and J.L. Granatstein, Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), pp. 196-201.

-

J.L. Granatstein, Who Killed Canadian History? (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1998), p. 117.

-

Kent Fedorowich, “‘Cocked Hats and Swords and Small, Little Garrisons’: Britain, Canada and the Fall of Hong Kong, 1941,” in Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 37 (February 2003), pp. 115-116 & 157.

-

Brereton Greenhous et al., Crucible of War, 1939-1945: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, Vol. III (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994).

-

See Brian Farrell and Sandy Hunter, (eds.), Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2002.

-

Brian Loring Villa, Unauthorized Action: Mountbatten and the Dieppe Raid (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1991).

-

Terry Copp, review of Unauthorized Action, in Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 72 (March 1991), pp. 123-124.

-

Charles G. Roland, “On the Beach and In the Bag: The Fate of Dieppe Casualties Left Behind,” in Canadian Military History, Vol. 9 (Autumn 2000), p. 23.

-

Norman Hillmer, “Defence and Ideology: The Anglo-Canadian Military ‘Alliance’ in the 1930s,” in International Journal,Vol. 3 (Summer 1978), pp. 588-612.

-

Lawrence Lai Wai-Chung, “The Battle of Hong Kong: A Note on the Literature and the Effectiveness of Defence,” in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 39 (1999), pp. 123-127.

-

Consul Robert S. Ward, “The Japanese attack on and Capture of the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong.” 18 August 1942, Box 412, File 6910, Hong Kong Operations, War Department Records, RG165, Entry 77, Military Intelligence Division, 1922-44, National Archives and Records Administration.

-

Bob Blakey, “Valor and the Horror Faces Firing Squad Again,” in The Calgary Herald, 6 October 1994.