This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

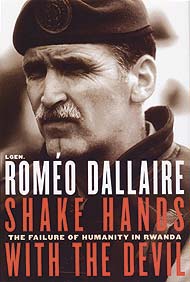

shake hands with the devil: the failure of humanity in rwanda

by Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire

Toronto: Random House Canada. 522 pages, $39.95

Reviewed by Judy Kennedy

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Is the use of force justified in the protection of human rights? If so, what kind of force? General Roméo Dallaire goes a long way in answering these questions with his gripping account of the United Nations’ Rwanda mission of 1993-4. He answers, too, the question: “Whose human rights?” Echoing the famous words of Zola to the French military in the Dreyfus affair, his “j’accuse” is aimed at the UN member states who contribute to such campaigns only if it’s safe, i.e., if international public opinion is supportive, if risking their soldiers’ lives is worth it, and if it is in their national interest to do so. Yet, if the United Nations stands for anything, it is that human lives are equally sacred.

Is the use of force justified in the protection of human rights? If so, what kind of force? General Roméo Dallaire goes a long way in answering these questions with his gripping account of the United Nations’ Rwanda mission of 1993-4. He answers, too, the question: “Whose human rights?” Echoing the famous words of Zola to the French military in the Dreyfus affair, his “j’accuse” is aimed at the UN member states who contribute to such campaigns only if it’s safe, i.e., if international public opinion is supportive, if risking their soldiers’ lives is worth it, and if it is in their national interest to do so. Yet, if the United Nations stands for anything, it is that human lives are equally sacred.

The book gives a detailed account of the UN response to the Rwandan crisis, which was initially designed as a small, classic peacekeeping mission to observe the implementation of the Arusha Peace Agreement along the borders of a demilitarized zone. The parties signing the accord, after two and a half years of civil war, were the rebel Rwandese Patriotic Front (Dallaire is silent on who supported them) and the Rwandese Government Forces, supported mainly by France. During a reconnaissance mission as Chief Military Observer, Dallaire realized that more troops would be needed; that the challenges to be confronted required military force. He lobbied for an expansion of the initial concept – and got the United Nations’ Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR). He was appointed Force Commander.

UNAMIR’s mandate was, in part, to facilitate the demobilization of the warring factions and the formation of the new integrated army; the repatriation and resettlement of refugees; and to secure the installation of an interim government prior to democratic elections. However, as evidence mounted that a genocide had begun – of Tutsis and moderate Hutus by militia, particularly the Interhamwe, and by government forces – Dallaire knew his forces couldn’t stop it, and he pleaded for more support.

That’s when we, the developed nations, let them down. Only after Rwanda captured the media’s attention did various nations offer additional forces and some matériel. By the time the number of troops rose from 2500 to 5500, the killing had abated and the rebel forces had won.

Those who see a viable, effective United Nations Organization as essential for a just, civilized world in a ‘new age of humanity’, will appreciate Dallaire’s critique of the workings, style and inadequacies of that ‘Goliath’. If collective, rapid intervention is to become a reality for the world’s hot spots, we know that changes must occur, and he identifies some of them. But his struggles to implement UNAMIR’s mandate – and then to expand it to reflect the horrific reality on the ground – are, quite simply, stunning.

The book’s title comes from the Interhamwe, bands of young punks armed with machetes and trained by members of the government forces to kill in particularly gruesome ways, just to show they could. One won’t forget Dallaire’s account of meeting its three leaders – shaking hands in the desperate hope of effecting change.

This story is also about the making of a peacekeeper. Dallaire was hired by the UN under civilian contract for the mission. His background included serving as Commandant of Collège militaire royal, a variety of staff positions, and Commander of 5th Brigade Group in Valcartier – where he trained troops in escort tasks and in convoy protection for the UN peacekeeping mission in Yugoslavia. Learning of his posting to Rwanda, he replied: “That’s somewhere in Africa, isn’t it?”

Insufficiently prepared in the legal, diplomatic, and socio-political aspects of the conflict, and in the mediative techniques required for its resolution, Dallaire felt he was “in uncharted waters”. His compensatory assets included a sensitivity to minority status, a moderate, conciliatory nature, readiness to learn, and a fierce determination to see the Peace Agreement implemented. Against overwhelming odds, he didn’t flinch in that undertaking. After a year of crises-from-hell, he handed over command of a revitalized peacekeeping force, finally of a size and calibre to again allow peace-building.

So what force is required to “maintain or restore international peace and security”, in given and changing circumstances? This is the only basis, self-defence aside, for the use of military force under the UN Charter.

Dallaire answers with a question: Had UNAMIR received the requested troops and capabilities in time, could they have stopped the killings? Absolutely. Experts agree. And had UNAMIR 2 followed his plan to swiftly repatriate the Zaire-based refugees, removing the genocidaires, and to resettle those displaced within Rwanda, security could have been restored to the whole region, sparing millions of lives.

General Dallaire is now special adviser to the Canadian government on war-affected children, and on the prohibition of small arms distribution. He warns that we, the United Nations, must remove the underlying causes of the rage that inflames those without hope of a better, fairer life. To use his phrase, “Allons-y!”

![]()

Judy Kennedy is a lawyer and activist in Halifax.