This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

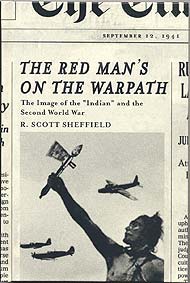

The Red Man’s on the Warpath: The Image of the “Indian” and the Second World War

by R. Scott Sheffield

Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press

232 pages, $103.93 (hardcover) or $36.62 (paperback)

Reviewed by Brian R. Selmeski

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

The Red Man’s on the Warpath is a theoretically sophisticated, methodologically innovative and exceedingly well-written study of the English Canadians’ image of the “Indian” from 1930 to 1948. The author is quick to point out that it is “not a work of Native history even though First Nations people form the subject .... Rather, it is an examination of an aspect of English Canada’s cultural history.” Nor is it military history in the traditional sense, although the period in question centres upon the Second World War. Consequently, the book may well disappoint readers searching for detailed accounts of Aboriginal martial exploits, or extensive data with respect to Native recruitment. However, those interested in war’s effects on the whole of Canada’s society, not just upon the military, and the cultural rather than sociological aspects of conflict, will likely

delight in this work.

The Red Man’s on the Warpath is a theoretically sophisticated, methodologically innovative and exceedingly well-written study of the English Canadians’ image of the “Indian” from 1930 to 1948. The author is quick to point out that it is “not a work of Native history even though First Nations people form the subject .... Rather, it is an examination of an aspect of English Canada’s cultural history.” Nor is it military history in the traditional sense, although the period in question centres upon the Second World War. Consequently, the book may well disappoint readers searching for detailed accounts of Aboriginal martial exploits, or extensive data with respect to Native recruitment. However, those interested in war’s effects on the whole of Canada’s society, not just upon the military, and the cultural rather than sociological aspects of conflict, will likely

delight in this work.

The book traces two distinct trends in the representation of Native Canadians, the “Public Indian” and the “Administrative Indian.” To determine the extent of public discourse, Sheffield painstakingly reviewed all references to Native people from a broad sample of Canada’s print media during the period in question. The approach was holistic, examining an unusually lengthy timeframe and emphasizing the contributions of non-journalists through letters to the editor, poems and cartoons. This permitted him to determine not just the dominant opinions of the day but also the values and norms that fed and sustained these beliefs. Sheffield concludes that the public image of the “Indian” was neither unitary nor static, but shifted over time between multiple expressions. He meticulously demonstrates how an emphasis on the “noble savage,” to laud Native past behaviour, and “drunken criminal,” to critique their conditions during the Great Depression, gradually gave way to the “Indian-at-war” as a means to promote national unity in the dark and early days of the war, and this is from whence the title was drawn. Finally, that public image morphed into the “Indian-victim,” as victory became more certain and Canadian gazes turned from winning the war in Europe to winning the peace at home.

To ascertain the nature of the “Administrative Indian” depicted by the government officials who controlled almost every aspect of Native people’s lives, the author examined archival records from the Indian Affairs Branch (IAB). These ranged from school files to internal correspondence, enlistment and conscription records, to testimony before parliamentary committees. Sheffield suggests that the IAB’s discourse was, on the whole, more resistant to change than that of the public on account of its construction and deployment by a relatively small troupe of long-serving officials. The image of the “Administrative Indian” was somewhat adaptable in the face of mobilization, total war and demobilization, but ultimately this image reflected those who crafted it and their desires. He concludes by noting that IAB’s “raison d’être needed to be framed within an unequivocal sense of superiority,” as “tampering with the pillars of racial superiority could destabilize the entire structure.”

Rather than treat these discourses as “social facts,” the author presents a highly nuanced treatment, never shying away from quirks, variations and ambiguities. His inclusion of these details and knack for using them to advance his argument is testament to the strength of both the writing and argument. Similarly, by explicitly framing the chapters with his research questions, the author engages readers in his intellectual quest, rather than presenting his findings as a fait accompli. This also makes the book ideal for use in undergraduate courses – the sort that has earned Sheffield a fine reputation with students at the University of Victoria. Nevertheless, the heavy emphasis on discourse often requires him to ascribe meaning(s) – or not – to slippery and shifting concepts. The results occasionally fall short, although findings are well contextualized, and the overall presentation is quite convincing.

Despite my high esteem for the book, it is not without its shortcomings, to several of which Sheffield readily confesses. For example, he justifies the complete absence of French-Canadian images of the “Indian” as falling outside his cultural and linguistic competence. Fair enough, but the author makes no apologies for a failing he could have easily addressed, that being gender bias. This weakness goes well beyond language choices that can be explained away as merely reflecting the highly masculine speech of the era, although the unspecified use of “men” occasionally left me wondering whether Native women were ever contemplated. Instead, it is his failure to subject the gendered assumptions and taken-for-granted beliefs behind these words to the same sort of critical analysis he does for the notion of “Indian” that troubles me. This limits the depth of the analysis, obscuring levels of meaning, while revealing others. A similar critique could be levied against the author’s restriction of the study to First Nations, essentially erasing non-Status, Inuit and Métis from the picture.

Perhaps most importantly, Native Canadian self-representation is strikingly absent from the first 140 pages of the text. “Indian” voices are finally heard only when the “Administrative” and “Public” images vie for supremacy in the Special Joint Commission of the Senate and the House of Commons (SJC) that considered changes to the Indian Act from 1946 to 1948. Native Canadians were vocal before this period, and integrating their self-images to the preceding chapters would have aided the author’s agenda of striking down stereotypes of “Indians” as passive. Nevertheless, the SJC was clearly an important turning point for Canadian Aboriginal affairs on many levels, most importantly, the successful insertion of Natives into the national debate on “Indian policy.” The terms of debate also altered, since none of the existing public or administrative images of the “Indian” proved satisfactory in resolving the legal-political-social-cultural conundrums faced by the SJC.

The resultant new discourse of the “potential Indian citizen” signalled the beginning of a shift from the traditional assimilation approach in which “Indians” were expected to become like “Whites,” to a more flexible model of incorporation. The author also contends that it marked “the beginning of the end” of the “Indian’s era of irrelevance” in Canada, rather than a definitive turning point, as is commonly asserted. While it could be argued that together these trends paved the way for contemporary notions of differentiated rights and multiculturalism, ultimately, Sheffield concludes, “even a war as pervasive as the Second World War can leave continuity in its wake.” He closes by noting that the “Administrative Indian,” not the “Public” or “Citizen” discourse, continued to exert the greatest influence over government policy well into the 1950s. Thus, as with all good books, the reader is left with questions as well as answers, particularly as to how this resistance was eventually overcome, to what degree and for whom.

The book’s hefty price tag may be one of its most significant shortcomings. However, the publication of a paperback edition (at almost one-third the price) in February of this year now puts it within the grasp of a much broader readership. This is good news, as The Red Man’s on the Warpath makes important contributions to fields as disparate as war studies and the social construction of race, while adding to multiple academic disciplines. That the book is also eminently readable and almost exclusively Canadian in content lead me to recommend it without reservation to a wide variety of audiences.

![]()

Brian R. Selmeski is an applied anthropologist at the Canadian Defence Academy, with a long-standing research interest in Aboriginal soldiers.