This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

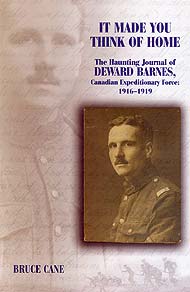

It made you think of home: The haunting journal of deward barnes, canadian expeditionary force, 1916-1919

by Bruce Cane

Toronto: The Dundurn Group, 2004

318 pages, $35.00

Reviewed by Major Andrew B. Godefroy

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Although memoirs of the Great War by Canadian soldiers are becoming increasingly available to military historians, only a handful have gained enough popularity to enjoy constant reference in publications dealing with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). More often than not, anecdotal evidence to support descriptions of CEF activity on the Western Front are drawn from a few classic works, such as Will Bird’s autobiography, Ghosts Have Warm Hands, Reginald Roy’s edited work, The Journal of Private Fraser, James Pedley’s autobiography, Only This: A War Retrospect, 1917- 1918, and, The Great War As I Saw It, by Cannon Frederick G. Scott. Further, Desmond Morton’s article, “A Canadian Soldier in the Great War: The Experiences of Frank Maheux,” attracts considerable attention for its avid description of a soldier’s wartime life through the eyes of a francophone Canadian.

Although memoirs of the Great War by Canadian soldiers are becoming increasingly available to military historians, only a handful have gained enough popularity to enjoy constant reference in publications dealing with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). More often than not, anecdotal evidence to support descriptions of CEF activity on the Western Front are drawn from a few classic works, such as Will Bird’s autobiography, Ghosts Have Warm Hands, Reginald Roy’s edited work, The Journal of Private Fraser, James Pedley’s autobiography, Only This: A War Retrospect, 1917- 1918, and, The Great War As I Saw It, by Cannon Frederick G. Scott. Further, Desmond Morton’s article, “A Canadian Soldier in the Great War: The Experiences of Frank Maheux,” attracts considerable attention for its avid description of a soldier’s wartime life through the eyes of a francophone Canadian.

Less appreciated, however, are equally detailed works, such as A Canadian’s Road to Russia, the letters of Stuart Tompkins edited by Doris Pieroth, and the more recently published Letters of Agar Adamson, edited by Norm Christie. For whatever reason, these and several others often go ignored by historians in favour of the few well-known memoirs mentioned above. Given the difficulties in attracting readership to what some may consider a small niche of Canadian military history, one may ask why invest the effort at all? Bruce Cane’s edited memoir, It Made You Think of Home: The Haunting Journal of Deward Barnes, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1916-1919, easily demonstrates the reward in pursuing topics in this field, and reminds us of the invaluable contribution that these first-hand records make to our overall understanding of Canada’s military experience on the Western Front.

Taking a non-traditional approach to this subject, Cane introduces the reader to Deward Barnes (1888-1967), a native of Toronto who volunteered for military service with the CEF on 26 February 1916. Enlisted with the 180th (Sportsmen) Battalion, he was later transferred to the 3rd Canadian Reserve Battalion and then the 2nd Canadian Entrenching Battalion. Finally, he was assigned as reinforcement to the 19th (Central Ontario) Canadian Infantry Battalion on 7 April 1917, just in time to observe his unit assault the heights at Vimy Ridge.

Although Barnes missed participating directly in that historic battle, it was not long before he underwent his own brutal baptism of fire. He survived the Battle of Fresnoy in May 1917, where his unit was severely mauled, to take full part in the battles at Hill 70 and Passchendaele later that year. In 1918, Barnes saw action during the German offensive in March-April, and was fully engaged in the Canadian battles during the last hundred days of the war. On 11 October, during the German counter-attack at Iwuy just past Cambrai, Corporal Barnes was shot through the right thigh by machine gun fire. Although not life threatening, his wounds were serious enough for him to be evacuated back to England where he survived the end of the war. He spent a brief period at Kinmel Park awaiting repatriation, but embarked for home prior to the outbreak of the infamous riots that took place there in March 1919.

In addition to combat, Barnes has also provided a vivid description of his other experiences on the Western Front that truly make his memoirs a worthy read. Perhaps most notable was his participation in the firing squad that assembled to execute Private Harold Lodge, a thrice-convicted deserter from his own company. In addition to personally escorting Private Lodge back to jail (who was handcuffed to Barnes), he described why he was chosen for this difficult duty, his reaction to it, and, finally, his feelings afterwards. Surprisingly, although Barnes showed distaste for the task and some degree of empathy towards the condemned man, he stopped short of being sympathetic towards Lodge. Barnes, who suffered through Passchendaele, may have felt little remorse for Lodge, who deserted his comrades and had missed the battle. Regardless, Barnes stoically did his duty on 13 March 1918, returned to his billet afterwards, wrote home and played cards. He made no mention of the matter thereafter.

Barnes’s rather subdued reaction to his role in the execution of Private Lodge is arguably the catalyst in the transformation of his character from recruit to veteran. During his early battles, Barnes described a sense of pure rush excitement that always overtook his fear, but after Passchendaele, his entries revealed a much more resigned and stoic soldier that had seen enough death and destruction to become no longer sensitive to it. His diary reported with frankness those soldiers he saw wounded or killed, but where at first he mentioned each one by name, by mid-1918, he simply made entries such as: “Shell came over, blew one man’s leg off. I can’t think whose it was.”

Barnes wrote his entries while at the front, but then transcribed all of his pocket diaries into a single volume in the winter of 1926. Never intending to have it published, he added some further detail and sketches and then left it on the family bookshelf as a personal memento for his son. The fact that it was completed so soon after the end of the Great War is one of its greatest attributes – the entries are virtually free of the political and historical baggage that accumulates in veterans’ memories as the events they experienced recede further into the past. In addition, Barnes was a remarkably unbiased soldier, and his balanced treatment of both his seniors and his subordinates in his writing marks a degree of maturity witnessed much less often in the diaries of other non-commissioned soldiers.

Cane is to be commended for his unique presentation of Barnes’s diary. Rather than simply introduce a self-contained daily memoir with no explanation, he has included annotative text where appropriate to support the entries, making the entire reading a richer and more detailed experience, especially for those readers who may be unfamiliar with the period. More importantly, he has placed each entry into proper context and, where necessary, corrected Barnes when his journal cannot be corroborated by other primary source evidence, such as brigade and battalion war diaries, official histories and the diaries and letters of other soldiers in the same unit. In doing this, Cane not only validates Barnes’s recollection of events, but also reminds readers and students of Great War history that no record is infallible of small errors.

Too often, soldiers’ diaries are taken at strict face value without any scrutiny or appreciation of time or events that may have influenced the writer. Historians, at times desperate to validate their own assumptions, may overlook discrepancies found in journals to prove a point. Cane, although obviously impressed by his subject, clearly resisted the temptation to fall in love with him and has, where appropriate, challenged Barnes’s recollection of events when dates, places, or persons could not be verified by other contemporary primary sources.

It Made You Think of Home is a valuable new addition to First World War Canadian biography. Map sketches from Barnes’s journal, as well as several photographs of him in France and Flanders, complement the work. The book would have benefited from a few operational maps of the places where Barnes fought, and the lack of an index is frustrating when searching for specific references to people and events. Still, the book includes a healthy bibliography, and the overall quality of the work is demonstrative of the increasing quality of Canadian military publications from Dundurn Press. Bruce Cane, author of, It Made You Think of Home, has produced a first-rate biography for both specialists and generalists to enjoy, and, hopefully, it will join or even replace some of the classics as a choice for characterizing the daily life of Canadian soldiers on the Western Front.

![]()

Doctor Godefroy is an instructor and course developer at the Royal Military College of Canada.