This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

International cooperation

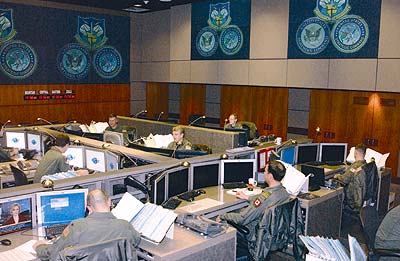

NORAD photo by Sgt Lawrence Holmes

The new command center of the Cheyenne Mountain Operations Center (CMOC), opened officially on 4 March 2005.

Shall we dance? The missile defence decision, norad renewal, and the future of Canada-US defence relations

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

On 24 February 2005, in the House of Commons, Foreign Minister Pierre Pettigrew announced that Canada would not participate in the American ground-based ballistic missile defence (GMD) system for North America. The relevant sentence ended with the phrase “at this time,” leading to speculation that a different political environment might lead the government to re-consider.1 Later that day in Question Period, however, the Foreign Minister used the phrase ‘this no is final,’ and since then, Prime Minister Paul Martin has reiterated the finality of the decision. However, it still remains unclear exactly what the government said ‘no’ to, and thus what ‘no’ is final, if you will. Even though Mr. Pettigrew also concluded: “This decision [was] based on policy principles and not sheer emotion,” neither the Prime Minister, the Foreign Minister, the Defence Minister nor any other government official has articulated these principles.

Even more problematic, no discussions, never mind negotiations, had been taking place with the United States on missile defence at the time. Negotiations had concluded well before the August 2004 agreement to permit NORAD to provide early warning data (known in NORAD parlance as Integrated Tactical Warning/Attack Assessment – ITW/AA) to the US GMD system. The basic framework for an agreement had, in fact, been established months before the beginning of formal negotiations following the exchange of letters between Minister of National Defence David Pratt and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in January 2004.

Adding to this puzzle, two days before the “no,” the new Canadian Ambassador to Washington, Frank McKenna, stated that Canada was already a participant as a function of the August agreement; an assertion quickly rejected by the government. Moreover, both parties in their statements when announcing the August agreement had clearly de-linked early warning from participation. Nonetheless, neither defined where early warning ends and participation begins.

DoD photo 971103-F-7902R-004

by Senior Airman Diane S. Robinson, U.S. Air Force

A U.S. Air Force E-3 Sentry airborne warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft touches down at 4 Wing Cold Lake, Canada, as part of an Amalgam Warrior mission, a NORAD air intercept and air defence exercise.

Of course, it is possible that the earlier negotiations defined participation, and the government has simply failed to make this public. But, if participation is not defined, then one does not know exactly what “this no is final” means. Recognizing that GMD remains a system in development despite its operational status, even US officials may have yet to decide the meaning of participation relative to early warning, and thus what was open to negotiations. From this perspective, the Martin government, or any future government, may go much further in engaging missile defence without violating existing policy. As a result, the government may be able to ‘have its cake, and eat it too’ on the missile defence file.

However, as the initiator, Canada publicly signalled a desire to participate. It effectively invited the US to dance. With Canada suddenly rejecting its dance partner, the decision represents a blow to the manner in which bilateral defence, if not broader foreign policy relations, are conducted with the Americans and other nations.

Within the sovereign state system, decision makers attach a premium to certainty, predictability and reliability. Every aspect of the missile defence issue appears to represent a blow to these values. This becomes even more problematic with the importance attached by the US to North American security in the war on terror, regardless of what Canada does or does not do. At least for the short term, and regardless of public negotiations, the decision provides an increased incentive for the US to dance alone or act unilaterally in its approach to North American security.

Of course, publicly, both parties will continue the rhetoric of cooperation and some of it will be translated into concrete action. But underneath, American officials may well have doubts about Canada’s reliability and credibility, which one would expect the government to recognize and seek a means to offset. This, in turn, explains why the ‘no’ was accompanied by an emphasis on Canada’s desire to contribute in other areas of North American defence and security cooperation, reiterated in the recently released Defence Review.

In effect, there is now an even greater incentive for Canada to move forward on further defence and security integration with the United States. The NORAD renewal process provides the means to demonstrate Canadian credibility and reliability and reduce US unilateralist incentives by expanding the relationship, but not necessarily the institution, into the maritime and land sectors.

In the end, the missile defence ‘no’ may go much further in creating an integrated North American security perimeter than otherwise would have been the case. Having done so, missile defence may simply follow one way or another. The Canada-US bilateral defence and security ‘dance’ will continue, but to a new tune.

The Participation/Non-Participation Shuffle

Ballistic missile defence is not new to the Canada-US defence relationship. From the 1950s until the early 1960s, Canada was a full partner with the US in the search for missile defence options. While Canada officially dropped out of the missile defence partnership, research cooperation continued in areas of significance for missile defence. Cooperative programs investigating outer space dynamics and sensing technologies, such as Teal Ruby, were all of relevance to missile defence development, and most were swept up by the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI). While sensitive to violating the 1985 policy prohibition on official government involvement, research was never equated with participation.2

This example is useful because it speaks directly to the problem of participation. Except perhaps for the interceptors and their kinetic-kill warheads, there is nothing that can be strictly labeled a missile defence technology. Basic research on upper level atmospheric and outer space dynamics is significant for a range of missions other than missile defence, including civil and commercial. Sensors designed to track objects in space, air, sea and ground potentially can also track missiles and warheads and cue interceptors.

For example, the original Safeguard Phased Array Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) radar in Cavalier, North Dakota, has remained part of the US ballistic missile early warning system (BMEWS), tasked primarily to cover ballistic missile submarine launches from Arctic waters. It has also been part of the US Space Surveillance Network (SSN) and it tracks thousands of objects in outer space as part of Space Track. In both functions, the data is transmitted to NORAD, and Canadians serve at Cavalier as part of NORAD.

Historically, early warning has not been seen as partici-pation in missile defence by the US, Canada, or the Soviet Union. During the brief operational life of Safeguard, the early warning mission was assigned to NORAD with no fanfare at all. At the time, NORAD was prohibited from participating in missile defence due to the 1968 ABM exclusion clause in the NORAD agreement.3

However, this perspective may be somewhat problematic if one references the now-defunct ABM Treaty relative to the status of Cavalier and the three core BMEWS radar installations at Fylingdales, Thule and Clear. The Treaty deals extensively with the radar issue, with explicit limitations laid out in Articles III and VI, and Agreed Statement F. The issue of the modernization of the BMEWS radar was also contested by the Soviet Union, with the Americans arguing that they had been grandfathered and thus their modernization was outside the limits proscribed within the Treaty.4 Even after ABM, the US negotiated memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with the United Kingdom and Denmark/Greenland to permit modernization for missile defence purposes.

Under ABM, and during the brief life of Safeguard, any Canadian involvement with this radar could have been interpreted as a violation of the Article IX prohibition, clarified by Agreed Statement G, on third party involvement, and the recent MOUs could be interpreted to equate involvement with participation. However, there is no record of concern emanating from the Soviet Union or the United States that any Canadian involvement with the radar and/or a NORAD role in providing early warning for the ABM mission violated the Treaty. Furthermore, the MOUs have not been clearly equated to participation by any of the parties.

DND photo IS2005-0055 by Sergeant Alain Martineau,

DGPA/J5PA Combat Camera

HMCS Vancouver sails beside the American USS Shoup while in formation off the west coast of Vancouver Island as part of Exercise Trident Fury. The exercise is aimed at advancing Canada’s ability to respond to offshore threats and unlawful acts from within a coalition environment.

Nonetheless, throughout the 1990s analysts within DND were concerned about the relationship between early warning and participation, especially given the government’s endorsement of the narrow interpretation of the ABM Treaty in the 1994 White Paper.5 Particularly illustrative of the issue was the US debate about the Treaty status of the future low earth orbit Space-Based Infra-Red (SBIRS-Low) tracking system. For some, the system, in providing ‘cold’ tracking of warheads transiting through outer space and cueing for the ground-based radars, violated the Treaty’s Article V prohibitions on space-based components. For others, the system was defined as an adjunct because this type of system had not been specified in Article II, and it did not communicate directly with the interceptors. In other words, it was not radar operating in an ABM mode, as defined by the Treaty.

As SBIRS-Low has yet to move out of the research and development phase, its Treaty status was never resolved. Neither, apparently, did Canadian officials come to a conclusion. As a result, the line between early warning and system participation remains blurred. If the system is an adjunct, then it is not a component, and involvement does not equate to participation. It could be reasonably seen as part of ITW/AA. In this sense, all the assets that provide data to NORAD ITW/AA are not missile defence components, and thus involvement with any of them does not mean Canadian participation.

Thus, for example, the planned space-based optical space surveillance satellite could theoretically provide information of relevance to the missile defence mission relayed via NORAD without violating current Canadian policy. This is not to suggest that the satellite would have any specific value to ballistic missile defence whatsoever. Rather, it simply illustrates that any sensor providing data to NORAD would be part of ITW/AA and thus would be linked to the US GMD system without entailing participation. In other words, as long as NORAD is the conduit, then any sensors, US or Canadian, would not conflict with existing policy.

Of course, this perspective does not distinguish between early warning and guidance to target. All radar/sensors provide some element of target tracking, and the modernized BMEWS will provide ‘high fidelity’ to direct other X-band radar to the target, which, in turn will serve to guide the launch of the interceptor and cue the on-board system that undertakes the final guidance to actual intercept or ‘collision’ in outer space. Within this process, there is no agreed line between adjunct and component or non-participation and participation. If accessing the existing space and ground-based early warning systems through NORAD is not participation, then even other tracking radar possibly deployed in Canada would not necessarily equate to participation either, as long as NORAD is involved.

Additional future radar installations in the eastern part of North America are on the horizon. The current operational system in Alaska is optimized for the most immediate future threat – North Korea. The system can also deal with missile tracks from launch points in the Middle East heading towards targets on the eastern seaboard. However, the system is not optimized for such threats. In responding to these evolving threats, currently focused upon Iran’s ballistic missile development program, the requirement for tracking and cueing radar – which would also serve a battle damage assessment function in eastern North America – emerges. Already, Raytheon, one of the prime contractors, has been looking at possible sites, including Goose Bay, and other possibilities may arise to provide warning of a failed intercept during an engagement.6 In addition, these radar stations would contribute to other missions, including the tracking of objects in space.

DND photo ISD01-6886 by Sgt Dennis Mah, DGPA/J5PA Combat Camera

A servicing technician performs a walk-around inspection of a CF-18 Hornet jet fighter after its return from a routine flight over the Atlantic coast. This Hornet, from 425 Tactical Fighter Squadron at 3 Wing Bagotville, was one of six brought to 14 Wing Greenwood after the terrorist attacks of September 11, when NORAD increased air patrols in the region.

As both threat and system develop further, the possibility that Canada would agree to deploy ‘early warning’ radar on Canadian soil without violating the February ‘no’ exists, regardless of the government in power. As long as NORAD remains ‘in the loop,’ policy has not been contradicted. The ‘line-in-the-sand’ in this regard would be cost, and the Prime Minister’s and Foreign Minister’s words to avoid missile defence investments in favour of investments in other areas of North American defence and security is not problematic for two reasons, notwithstanding a lack of evidence that the US would require a Canadian monetary contribution.

First, limited investment in radar serving other defence and security functions, which entail sovereignty missions to track hostile or threatening aerospace objects, is not inconsistent with existing policy per se, and it is emphasized in the Defence Review. It may stretch the policy, but it would not violate it. Second, the longstanding favourable NORAD infrastructure cost-sharing arrangements would limit demands on the Canadian defence budget. How far the US might go in negotiating a special one-time arrangement could well be the key in the future.

Regardless, in the absence of an articulated policy position, the possibility of an evolving Canadian relationship with the US GMD system within existing policy parameters exists. Canada may well end up participating even more than it already is “not participating.” In this regard, command and control considerations also emerge. For most observers, participation was not about radar/sensors, but rather command and control of the system. It was in this context that one could interpret the repeated government statements since June 2003 that Canada should have a seat at the table concerning any intercept taking place over Canadian territory, even though the actual intercept would take place in outer space, which is legally equivalent to international waters.

The statement, reiterated by the Prime Minister after the “no,” implied Canadian input into the intercept decision process. In so doing, he may have only meant Canadian input into mission planning concerning intercept strategies and defence priorities in the likelihood of an attack. If this is the case, then the government may also believe that such input does not equate to participation. However, once one takes this step, assuming the Americans would agree, one is also engaged in elements of command and control. Once this door is opened, the possibility of operational involvement emerges, and, in one way, such involvement already exists.

Ideally, an effective system should be able to react quickly in order to take multiple shots at an incoming warhead – the overall logic behind the layered approach of US missile defence plans. For the GMD system, the more autonomy given to the missile defence command, the quicker the ability to react and evaluate whether another interceptor is required. As such, NORAD’s ITW/AA mission, in assessing that North America is under ballistic missile attack for the US GMD system, is tantamount to a decision to fire. However, NORAD has no say in the details of the firing decision.

Regardless, like the radar/sensor question, there is no clear delineation of the relationship of command and control concerning participation. Even the ABM Treaty did not specify command and control in Article II that defined an ABM system and its components. Only interceptors and radar/sensors directly tied into them appear to equate to actual participation. Thus, even in command and control terms with the mission assigned to Northern Command, it remains unclear exactly what the government said no to relative to the negotiations last year.

In part, the overall issue of defining participation may have simply been a function of the US not knowing the answers to these and many other questions with a system still in the development stage. However, if this is the case, the ‘no’ does mean that these decisions will now be taken only by the US with no Canadian input. For a nation that has sought consistently to move the US away from unilateralism, the ‘no’ may generate American unilateralism – a shift in the dance further affected by the process through which the decision was made.

Surprising Your Partner in Mid-Dance

Most observers, including opponents of missile defence, expected Paul Martin to lead Canada into missile defence by having the mission assigned to NORAD. Whereas much of the public debate suggested that the US was pushing Canada to join, the Bush Administration had not singled out Canada in its invitation to allies. Even President George W. Bush’s statement in Halifax on November 2004 was rather generic in expressing a “hope” of cooperation. While his statement was interpreted as a demand, fed in part by the Prime Minister’s response that Canada was a sovereign country and would decide on its own, the President’s “hope” is more appropriately seen as a positive response to Canadian signals. Thus, as late as November 2004, it would appear that the US President believed that Canadian participation was simply a matter of time and negotiation.

Such a belief reflected a process that had been initiated by the Chrétien government, and advanced much further within the first two months of the Martin government. In so doing, roughly 35 years of Canadian policy was reversed, notwithstanding the shift that had occurred in the 1994 Defence White Paper.7 For a variety of reasons, successive governments had made it clear to the US that Canada would not participate in ballistic missile defence. As a result, US missile defence, as it concerned continental North America, evolved under a ‘US only’ assumption. Ideas that the system, originally billed under the label of National Missile Defense (NMD) in the 1990s, would be more effective if Canada became involved overwhelmingly came from Canadian observers, as did fears that the future of NORAD was at stake, up until the attacks on 9/11.8

Unless Canada signalled a shift in policy, the Canadian answer, based upon past policy would be ‘no’ and so the likelihood of any invitation from the Americans to participate would be near zero. Allies and good neighbours do not issue public invitations, knowing the answer will be a negative one. In fact, even a hint of interest, given Canadian domestic sensitivity to any notion of US pressure, would be counter-productive if the American goal was to get Canada to participate. The history of missile defence and the broader political relationship essentially forbade the US to ask Canada to dance in this field. At best, the US could have left the door open by reiterating the value of defence cooperation with Canada, and extending an invitation to all allies, which it did in 2002 following the decision to withdraw from the ABM Treaty.

On the Canadian side, one would expect that this environment would also be well understood. Until the December 2002 deployment announcement by President Bush, the position of the Chrétien government had been the four negatives: no architecture, no deployment decision, no invitation and nothing to decide. In a minor way, it signalled that Canada might be willing to dance if asked, or perhaps only recognized that once a deployment decision was announced, a decision would be made one way or another.9

Once President Bush announced an operational date for GMD, it was up to Canada to move forward, and the first abortive movement was a high level meeting with the Missile Defence Agency (MDA) in Washington at Canada’s request in January 2003. The meeting produced little because the Canadian delegation had no mandate to move beyond seeking information about the system, and the MDA had little to offer, as GMD was a ‘US eyes only’ system. Thus began the process that would lead Canada to invite the US to the missile defence dance, and missile defence came to appear as an implicit means to improve Canada-US relations that had been negatively affected by the war in Iraq and other irritants.

In a speech to the Canadian Newspaper Association on 30 April 2003, Prime Minister Martin signalled not only the importance of improving relations with the US but also the need for Canada to become involved in missile defence for North America. Shortly thereafter, the Chrétien government moved forward. Minister of National Defence John McCallum announced in the House on 29 May 2003 that the government had “decided to enter into discussions with the United States on Canada’s participation in ballistic missile defence.”10 In so doing, he noted only one caveat to possible participation: the weaponization of outer space. Even then, he argued “if we [Canada] are not inside the tent our ability to influence the US decisions in these areas is likely to be precisely zero. If we are a part of ballistic missile defence, then at least we will be inside the tent and be able to make our views known in an attempt to influence the outcome of this US decision.”

From this announcement followed discussions between the parties, which laid the outline of an arrangement by October 2003. Subsequently, Paul Martin, upon becoming Prime Minister, reiterated the importance of participation in December 2003. In January 2004, the incumbent Defence Minister, David Pratt, requested formal negotiations in a letter to Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld. “It is our intent to negotiate in the coming months a Missile Defence Framework Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the United States with the objective of including Canada as a participant in the current US missile defence program and expanding and enhancing information exchange.”11 In emphasizing NORAD as the centerpiece for participation, he also noted that the US was “prepared to consult with Canada on operational planning areas.”12

As a first priority, the Minister’s letter suggested rapid movement to use NORAD for the early warning mission for GMD. Eight months later, Mr. Pettigrew, in announcing the NORAD amendment, separated it from the missile defence decision and suggested that the primary purpose was to safeguard NORAD as an institution. The missile defence decision was supposed to follow after the conclusion of further negotiations. It appears that nothing developed further until the Bush visit in November, which set off a relative firestorm. But even then, subsequent remarks by the Prime Minister provided no indication of what would follow in February.

In his December interviews with the press, the Prime Minister spoke directly to missile defence policy parameters. He laid down three primary markers: no interceptors on Canadian soil, no weapons in outer space, and no money for missile defence. However, none of these could be interpreted as preparing the ground for a policy reversal. All three could be more readily considered to be laying the basis for moving forward.

Concerning the first two, neither was of any relevance to the system at hand. As a ‘US only’ system, speculation of an additional site had been limited originally during the NMD years to the original Safeguard site in North Dakota. Otherwise, discussions of a third site in the eastern US had been entirely speculative. Furthermore, the US had entered into discussions with East European allies on the possibility of a second site. Regardless, the US had never even hinted at requesting Canadian territory as an interceptor site.

Outer space weaponization is even further removed from reality. There is no shortage of speculation about weaponizing outer space for purposes that include, but go beyond, missile defence. But all the speculation, for and against, recognizes that the cost-effective technology to entertain the option rests at least a decade or two into the future. More importantly, it is not part of the GMD system whatsoever, especially with the space component of missile defence assigned as it isto US Strategic Command.

Finally, there is the issue of cost. With NORAD as the centerpiece for Canadian participation, the cost issue falls into longstanding funding arrangements on capital or infrastructure and operating costs. Canada has only paid a share of NORAD capital costs on Canadian soil – and nothing for infrastructure on American territory.13 With a US-based system, there are no infrastructure costs. Concerning operating costs, traditionally distributed on a 90 per cent American – 10 per cent Canadian basis, much would depend on the negotiations relative to the definition of participation. However, with NORAD providing ITW/AA, even as a non-participant Canada will face some costs relative to operationally linking GMD into the NORAD system as part of other modernization costs that affect operating costs.

In the end, nothing from the government indicated a volte face was in the offing. At best, the Americans may have expected no decision because of a shift in public opinion, a divided caucus, and the possibility of a motion opposing missile defence from the youth wing of the Liberal Party at its national convention.14 But nothing in government statements hinted that it was about to make the decision that actually transpired.

A New Dance

On the surface, NORAD renewal is neither controversial nor problematic. Whatever the concerns expressed in the past about the future of NORAD, they were laid to rest by 9/11. The air defence mission was resurrected and its aerospace control function reaffirmed, and subsequently it acquired the missile defence ITW/AA mission. And in the future, Canada will also contribute directly to the Space Surveillance Network.

The expansion of binational cooperation also appears inevitable, although the exact structural form and timing of the integration process remains to be seen. Both parties recognize the need for expanding the relationship into the maritime and land sectors. Canada in particular has restructured its approach to national/North American defence and security vertically and horizontally, and stressed this mission priority through existing and planned investments and the National Security Policy and Defence Review. Above all else, the proposed Canada Command provides an institutional response to, and point-of-contact for US Northern Command – both essential for expanded cooperation and the creation of a North American security perimeter.

However, neither is as straightforward in substance as they appear, due to the missile defence decision. Not only does the decision substantively move NORAD out of a meaningful aerospace role (but not air defence), it also may have generated an atmosphere of some doubt regarding Canada’s reliability as a partner. The government may reiterate the importance it attaches to national/ North American defence and security cooperation, continue to invest to demonstrate its sincerity, and push to institutionalize expanded cooperation, but doubt might well remain in the minds of the Americans.

As such, the United States will likely ‘hedge its bets.’ In other words, North American defence and security could well evolve into two parallel forms – the official and formal bilateral Canada-US structure, and the unofficial substantive unilateral US structure. These two forms are likely to emerge in the NORAD context despite the ITW/AA agreement.

In agreeing to the ITW/AA mission, both parties stressed the centrality of NORAD and separated it from the GMD participation question. Recalling that this mission is supported entirely by US assets, American agreement made sense on several grounds. First, the system, with its well-tested protocols and procedures, was already in place. It made little sense to create another system, especially with GMD confronting a range of other major questions and decision-points on its path to operational status, while still in the developmental stage. There was no need to place another issue on the table when the question of early warning could be readily resolved.

Second, and closely related, other parts of the US layered missile defence architecture lagged behind GMD. Although overall control has been assigned to Strategic Command, issues concerning the integration of the various layers remain in the future. It made little sense to deal with the early warning element until the overall system integration process began. Thus, leaving ITW/AA with NORAD represents a logical short-term solution.

Third, the US still needs some mechanism to provide Canadian authorities with warning of a strategic missile attack, and direct Canadian involvement continues to make political sense, rather than giving full responsibility to inform Canadian authorities to a ‘US only’ command. This underpinned the longstanding ITW/AA link between NORAD and the US strategic nuclear deterrent via the US national command authority (NCA). NORAD ITW/AA for missile defence simply replicates this link.

Finally, it was the logical first step in the process towards Canadian participation, as signalled in the Pratt letter. As such, US agreement represented a firm indication that GMD was open to Canadian participation. Like the ITW/AA decision itself, there remained many issues the US needed to resolve before it could fully engage Canada in negotiations about participation.

With missile defence apparently gone, however, the US calculus begins to change. It still needs the NORAD mechanism to provide Canada a warning of strategic attack. It does not need NORAD, however, to provide ITW/AA to GMD. NORAD is not necessarily the only conduit of data to GMD command. Others exist, including Strategic Command and Air Force Space Command. As future components of the layered system come on line and the components are integrated together into a single system, NORAD’s ITW/AA for GMD becomes increasingly problematic with Canada on the outside of missile defence. At best, it becomes a redundant ITW/AA system, with its primary function to inform the Canadian National Command Authority of strategic attack and, in turn, the success or failure of intercepts.

Furthermore, assessment takes on a different nature in the missile defence role. In the strategic nuclear retaliatory situation, assessment is essential because the cost of an error is nuclear war. Time is also available for assessment because of the relatively long flight times of ICBMs (roughly thirty minutes) and short time needed to launch a retaliatory strike, which is less than five minutes.

The missile defence time cycle is much shorter, especially for a system seeking as much time as possible to allow for multiple intercept opportunities. Moreover, a quick assessment error with a kinetic-kill warhead has miniscule costs when compared to nuclear weapons. With little time and low costs, an intercept launch decision can be moved well below the level of the national command authorities. In so doing, the actual extent to which an assessment takes place for missile defence is open to debate. Data from the warning, tracking and cueing sensors is vital to GMD command, but the assessment is likely to be immediate and simultaneous by officers in GMD and NORAD. NORAD might be a conduit of this data to the command, but its assessors are redundant, except for notifying the national command authorities.

Marginalization of NORAD and Canada further follows from the problem of differentiating missile defence from other missions as part of the US system of systems architecture. The common operating picture for missile defence will be the same as for global situational awareness, precision strike and the full range of US defence and security missions. Depending upon the US interpretation of the boundaries of missile defence, Canada may be excluded from any and all information concerning these systems, including operational characteristics, components, adjuncts and technologies, because they are also part of missile defence.

Early anecdotal evidence indicates the missile defence boundary will be a large one, thereby excluding Canada from a significant amount of information and access.15 As a result, Canadians will see less and less of the global strategic picture, and will know less and less about actual US strategic developments and thinking. NORAD, which was once Canada’s window into the global, strategic world and American thinking and planning, will probably become a marginal, ‘North American only’ institution, substantively only dealing with the air environment, notwithstanding expansion elsewhere.

If this is to be the future of the Canada-US dance in NORAD, then what of expansion of the relationship? There is little doubt that both parties have an interest in expanding cooperation. The logic for Canada relative to the idea of defence against help remains in place, especially in light of some perceptions in the US that Canada is a ‘soft’ backdoor for terrorists. Whether the government truly believes that Canada is directly threatened is moot. Canada has to dance with the US in pursuit of its own interests.

The problem for Canada is the message contained in the missile defence decision. Effectively, Canada informed the US that it is their responsibility to defend Canadian cities from ballistic missile attack. Deciding which city to defend is also a ‘US only’ responsibility. If Canada is willing to cede this part of defence to the Americans, then US officials might well wonder what else could be ceded to them.

From an American perspective, if the missile defence decision is vulnerable to the vagaries of public opinion and short-term domestic politics, then future, expanded cooperation may be just as vulnerable. With the premium placed on actual security in the US, how reliable is any Canadian commitment? Public opinion may support further integration now, as it supported missile defence in the past. But when, or if, it shifts, will Canadian decision makers stand fast?

The safe road for the US is to move cautiously forward on expanded cooperation, while planning to back up a bilateral system with a parallel unilateral system. Moreover, the Americans are likely to leave the initiative to Canada. As a result, Canada may well be able to define the scope of cooperation. The question will be whether it truly matters. Certainly, integrating the maritime picture and developing plans for coordinated land responses to a catastrophic event, man-made or not, makes sense for both parties. But behind the agreement, whatever its end state, one may well expect the US to develop alternatives.

Akin to missile defence participation, neither party is likely to have fully developed plans for expansion and further North American defence and security integration. Both still face issues concerning their respective national structures and processes. This is especially true for Canada where Canada Command remains a proposal. Certainly, the template provided by the Binational Planning Group’s (BPG) recommendations is a starting point. Specific steps can be taken by linking national centres, such as the Canadian interdepartmental Marine Security Operations Centres, into the NORAD complex. However, one should not necessarily expect a great amount of movement in the NORAD renewal context, and it may be just as likely that the BPG’s mandate is renewed as part of a basic rollover of the agreement and/or the emergence of a separate negotiating process.

In the end, the many issues that both parties confront in relation to expanding Canada-U.S defence and security cooperation into the maritime and land sectors should serve to slow the process. But, Canadian officials may also perceive a slower process as a sign of US unilateralism in North America. In this sense, it might well be linked to the missile defence decision. Ironically, this could push the government to move faster in seeking expansion and further integration. In effect, the more the US slows the process, the more Canada may seek to speed it up.

This represents a new dance for the partners. In the past, the US has always been perceived as the initiator and driver of new venues of cooperation in North American defence. Canada has always responded and sought to slow the process with caution as its guide. The US has led and Canada has slowly followed. The missile defence decision might well lead to a reversal of dance roles – a bolder Canada and a more cautious United States.

Conclusion

There is always a danger of placing too much significance on a single issue or decision. Thus, missile defence critics suggest the decision is not going to have serious, if any, implications for Canada-US relations. Linkage politics are not a feature of the relationship, such that missile defence would have had no impact regardless of the decision on the softwood lumber dispute, the mad-cow scare, or the diversion of salt water from Devil’s Lake, North Dakota into Manitoba. Even in defence, the US needs Canadian cooperation against terrorist threats. It is economically vulnerable, like Canada, to any decisions that create barriers to the flow of goods across the borders. Finally, the relationship continues to be relatively immune to high-level political disagreements. Most of the relationship is conducted far below the political spotlight by military and civilian equals with similar views and ideas.

Unfortunately, such views are at odds with the primacy placed on national security in American political culture. Linkage politics may not result. But, the decisions to cede a part of a nation’s defence to another state could be viewed as troubling and raise concerns about Canada’s actual commitment to North American security. It is also at odds with the priority and significance attached to missile defence by the Bush Administration. If saying ‘no’ was really about the government playing the nationalist card, one is hard pressed to think that there will be no consequences, particularly given the apparent about-face.

Finally, good relations may continue between counterparts managing the defence relationship on a day-to-day basis, but the aerospace as distinct from the air component has been ripped out of the relationship. Of course, the space side of the aerospace arrangement has always had a dubious future. Canada’s all-party consensus on the non-weaponization of space is problematic for Canada-US cooperation, whether or not weaponization occurs.

The missile defence decision may not be a watershed in the relationship. It may only represent the penultimate step in a process begun decades ago of drifting apart and leading to a new relationship or dance. Of course, the February announcement may not be the final word on missile defence as well. But the nature and the process of the decision strongly suggest that a significant transformation in the relationship will occur. Canada and the US will continue to dance, but probably to new steps.

NOTES

![]()

Dr. Fergusson is the Director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at the University of Manitoba.

Notes

- Pierre Pettigrew. “Statement to the House of Commons”. Hansard. February 24, 2005.

- In September 1985, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announced that, officially, Canada would not participate in SDI (a research program), but would allow Canadian companies to do so. The 1994 White Paper effectively negated this policy by opening the door to official government participation. According to the Foreign Minister’s statements, the February announcement appears to revert government policy back to the Mulroney years. “Pettigrew endorses Canadian industry ties to missile defence” CBC News. February 27, 2005.

- The exclusion clause was dropped in the 1981 Renewal. It remains unclear whether the proposal to drop the clause came from Canada or the US. Regardless, it was seen by Canadian decision makers as irrelevant and a nuisance in light of the prohibitions on third party involvement in the ABM Treaty.

- See Appendix A. Matthew Bunn.. The ABM Treaty and National Security. Washington: The Arms Control Association. 1990.

- On the interpretation debate. Ibid. p. 58-70. National Defence. The 1994 Defence White Paper. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1994. p. 16

- David Pugliese. “Raytheon, Lawmakers Lobby Canada for Radar”. Defense News. March 14, 2005.

- The 1994 White paper reversed the 1985 Mulroney policy in allowing for official government engagement to explore possible Canadian involvement.

- See James Fergusson.”Where to From Here: The Ongoing Saga of Canada and a Limited Ballistic Missile Defence for North America” Policy Options. April, 2002

- President Bill Clinton’s announcement in September 2000 that NMD deployment would not proceed eliminated concerns within National Defence that Canada would be forced to make a decision.

- John McCallum. “Statement to the House of Commons”. Hansard. May, 29, 2003.

- David Pratt, Minister of National Defence. Letter to Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld. January, 2004. Interestingly, the letter and the positive reply have been deleted from the DND website.

- Ibid.

- Historically, Canada paid one-third of capital costs, except for a 40 per cent share in the modernization of the North Warning System in the 1980s.

- In 2001, for example, 76 per cent of Canadians supported missile defence. In November 2004, 56 per cent opposed missile defence. In a Compas poll right after the decision in February, 54 per cent were opposed. However, the same poll found attitudes of Canadians very soft on missile defence. See. Compas Survey for National Post. Missile Defence: Small, Soft, Quebec Majority Opposes It in Practice, While Backing It in Principle, Big Majority Condemns Ottawa’s Lack of Public Discussion. Compas Inc. February 28, 2005.

- This assertion is drawn from developments that have occurred over the last several years in the NORAD world where Canadians have been excluded from areas and information to which they previously had full access.