This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

History

CWM 1971026-4123 painting by Anthony Law

Windy Day in the British Assault Area.

c. anthony law master and commander

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

With the establishment of the Canadian War Memorials Fund, and the appointment of official war artists to record Canada’s efforts during the First World War, the dye was cast for another programme a generation later in the Second World War. At the onset of hostilities in 1939, Britain was first off the mark in the production of war art with its War Artist Advisory Committee modeled upon Canada’s First World War programme. In Canada, William Lyon MacKenzie King’s government, lacking enthusiasm for a similar initiative, delayed sanctioning the Canadian war art programme until late 1942, three years after Canada had entered the fray. Once formalized, the initiative, known as the Canadian War Records Programme, offered 151 officer billets to serving personnel bearing the appropriate artistic credentials. Three of the billets went to naval artists dedicated to the portrayal of the Canadian navy at war, “vividly and veraciously.”2

After the war, Vice-Admiral G.C. Jones, Chief of the Naval Staff, in attesting to the importance of the war art collection, wrote: “The cold realism of the camera and the vivid colours of the painter have given the people of Canada in this war a far greater knowledge of the work and objectives of their navy than they ever had before.”3

This article will discuss the wartime service and career of Charles Anthony Law, who was twice commissioned to participate in the Canadian War Records Programme. Tony Law, already a serving officer in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), was uniquely qualified to do the job, based upon his purely military accomplishments, and professional training as an artist.

Early Influences

Born into a life of privilege in 1916 to Canadian parents living in London during the Great War, Charles Anthony Law grew up in Quebec City, spending alternate summers at the homes of his grandparents in Muskoka and on the Gaspé. Demonstrating an early propensity for working with his hands, Law built his own sailboat, and became an avid, skilled yachtsman. He showed an equal love and talent for painting, and was encouraged by his mother as well as grandfather Law to become an artist. However, his maternal grandfather, a retired judge in the Exchequer Court, “frowning on his artistic aspirations,”4 persuaded him to pursue a more traditional education at the University of Ottawa. This took place during the Depression, money was short, and an offer of financial support by his grandfather was irresistible. Law left Quebec City for Ottawa.

In 1935, family friend and anthropologist Dr. Marius Barbeau5 of the National Museum of Canada introduced Tony Law to Eric Brown’s collection of the Group of Seven at the National Gallery of Canada.6 Brown had been collecting the Group’s works since 1922, and his collection was amassed in the Victoria Memorial Building, the current home of the Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Law was captivated. This visit was followed by a membership in the Art Association of Ottawa, and studies under Franklin Brownell, Frank Hennessey and Frank Varley,7 all of whom provided him with the impetus to follow his preferred career choice.

CWM 19710261-4067 painting by Anthony Law

Decommissioning, Rainy Weather, Sydney, N.S.

Hennessey was particularly attentive, taking Law on painting expeditions in the Gatineau Hills and the Gaspé, teaching him how to capture reflections on water, and introducing him to the colours of snow. In later life, Law made several trips to the north while serving with the Royal Canadian Navy, developing a penchant for black water, blue glaciers and towering icebergs. After retiring from the military, he visited the north seven more times, including a trip in 1996, the year he died. One of his last paintings Melville Bay, Greenland speaks of Hennessey’s influence throughout Law’s 60-year career.

In his first solo exhibit in 1937 in Quebec City, Law’s “strong, virile treatment” and the “typical Canadian character”8 of his landscape paintings were recognized by notable critics. At the age of 21, Law was awarded the prestigious Jessie Dow Prize9 for his entry Approaching Storm. Winning this prize gave his career the same boost as RCAF war artist Carl Schaefer experienced when he won the Guggenheim Fellowship.10

Law went on to study in Montreal with respected Julian graduate, Percyval Tudor-Hart.11 “He worked me hard during those two and a half years I had with himHe taught me all I know about composition, the mixing of colour, colour harmony, what to do, and what never to do,” said Law.12

To War

With the outbreak of war in 1939, Law joined the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR),13 and, because of his previous sailing experience, he was immediately assigned to His Majesty’s Royal Coastal Fleet driving motor torpedo boats (MTB) with the Royal Navy (RN) in England. The MTB was a small, fast and muscular warship with a crew of 17, armed with torpedoes and depth charges. The craft were designed to operate in shallow water, and the MTB crews were renowned for their daring as they sped in and out of enemy territory, harassing enemy coastal convoys, engaging with German E-boats,14 and drawing German destroyers from safe havens to within range of Allied warships. This highly dangerous and stressful activity came with a price, and Law, Mentioned in Dispatches15 twice, painted “to keep sane.”16 And his artistic undertakings during this period did not go unnoticed.

Despite the initial lack of an endorsement of an official Canadian war artist programme by the government,17 the Right Honourable Vincent Massey, serving in London as the High Commissioner for Canada in the United Kingdom, was keeping a watchful eye on servicemen in England who were professional artists. In 1942, Massey, after seeing two paintings by Law in an exhibition organized by Kenneth Clark, wrote H.O. McCurry, Director of the National Gallery of Canada:

Although the real scheme for Canadian war artists is still to be organized, there are, as you know, two or three people painting activities among our services hereThere is a young officer named Law, who was an art student before the war, who has produced some very striking canvases in the few hours he gets away from his motor torpedo boat in the Channel.18

In 1943, the RCN introduced its own MTBs into service with the British fleet. While awaiting delivery of the ships, Law was appointed a temporary official war artist for 10 weeks, and he was posted to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. Scapa Flow was a strategic northern anchorage where the Home Fleet could safely deploy ships to protect convoys in the North Atlantic, as well as those running supplies to the port of Murmansk in Russia. During this time, Law recorded the mightiness of the northern-based Fleet with ship portraits of His Majesty’s Canadian Ships (HMCS) Haida, Chaudière, Huron, and Restigouche, demonstrating a certain joie de vivre19 for his temporary employment. An example of his work from this period is his HMCS Huron.

Overlord and Beyond

After the long battle against German U-Boats in the North Atlantic subsided during the spring of 1943, the naval war shifted to the English Channel in preparation for the D-Day invasion. Canada’s armed forces would play a major role in this campaign. Two flotillas of MTBs, including Law’s 29th Flotilla and several Canadian Tribal class destroyers, joined the British 10th Flotilla, bolstering the fast-striking British fleet out of Plymouth, England. Embarking on chilling, night-time sorties involving “high-speed brawling in the dark”20 with enemy forces, the Fighting 10th’s primary role was to destroy enemy warships21 in the Channel area and to soften enemy defences for the invasion. On the day of the invasion, Law launched 15 attacks on enemy forces and was recognized with the Distinguished Service Cross22 for his bravery.

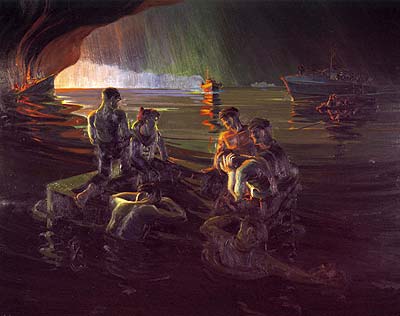

CWM 19710261-4119 painting by Anthony Law

Survivors, Normandy, Off Le Havre.

Unlike war artist Orville Fisher, who landed with the invasion force, all the while sketching on waterproof paper,23 life aboard an MTB was not conducive to en plein air painting and sketching. Law relied on his prodigious memory to recall the night actions he experienced, producing a myriad of sketches24 and paintings25 depicting the MTBs roaring about on the Channel during the Normandy operations. The pen-and-ink Battle with Six R-Boats off Le Havre, 6/7 June 1944 is an example. The Toronto Telegram described Law’s work as “vivid reactions of an artistic nature to the opulent colour, the swift action and the stern discipline of maritime warfare in the North Atlantic waters.”26

CWM 19710261-4057 painting by Anthony Law

Canadian Tribal Destroyers in Action.

Law’s naval artist contemporaries shared different challenges as they attempted to record life at sea in convoys crossing the Atlantic. Grant MacDonald, Tom Wood, Frank Leonard Brooks and Harold Beament, frustrated by long sea voyages and little action to record, turned to portraiture27 and depicting the daily routine of sailors at sea. On the other hand, Law, in the midst of the fray on a daily basis, and seeing more than his share of action, focused on capturing the overall image of the working warship.

Law described the terrible beauty of battle as follows:

Certain subjects, phases of battle, for instance, form unforgettable scenes in one’s mind. Such as lovely designs of star shells, flak and the horrors of war, ships sinking or on fire I remember a certain night when we met a large enemy convoy heavily escorted. They put twelve star shells into the sky that was looking so beautiful. It was just like the 24th of May. That was the subject of my painting showing our boats in the middle of the night, with all the details shown because of the brilliant light coming from the star shells. And as the battle was progressing, dawn broke east and we could see the enemy convoy ships silhouetted against the horizon. That was a scene that I can still see today in my mind. It was simply unforgettable. And it was easy to reproduce it on the canvas.28

For nine months, the MTBs continued to engage the enemy close to the coasts of France, Belgium and Holland, suffering a 37 per cent casualty rate in the process. In his White Plumes Astern, Law chronicles the short, daring life of Canada’s MTB Flotilla, speaking frequently of the courage and camaraderie of his crews. However, in February 1945, disaster struck his particular flotilla while they were berthed alongside at Ostend, Belgium. A fuel accident destroyed the MTB unit and took the lives of 64 sailors. Law, in England at the time, was staggered by the news. With victory in Europe imminent, the need was diminishing for a large coastal defensive fleet, and a decision was taken not to rebuild the 29th Flotilla, leaving Lieutenant-Commander Law without a command.

Home Again

Repatriated to Canada, Law was reassigned to the Canadian war art programme, where he remained until its termination in 1946. Greatly affected by the loss of his men and the MTB fleet, he painted prolifically “over the next nine months,” as if “trying to paint the war out of his system.”29 Law’s work lost its “youthful confidence,”30 and took on a uncharacteristically sober and tragic tenor. His Graveyard Sorel depicts paid-off Corvettes at the end of the war awaiting disposal. In this painting, an atypical stillness permeates the air, as the ships, no longer of any use to the RCN, appear to forlornly await their fate. Law achieves this quietness with deep reflections, a brooding palette of purples and repeated verticals. Leonard Brooks’s light and airy watercolour of the same subject Ghost Ships, Halifax is almost cheerful in comparison.

Figure drawing admittedly challenged Law, and he preferred only to include people in his work to “give perspective and scale.”31 His pen and ink sketch, Carpenter Girls in Cool Green Overalls illustrates this use. However, in his emotional portrait32 Survivors, Normandy, he makes an exception, given his familiarity with the subject matter. Painted during his mourning period, the work is a reconstruction of the torpedoing of an MTB and the rescue of its exhausted crew. They are portrayed clinging to floats in the foreground, and alongside the MTB in the distance. Apart from the conflagration consuming the sinking boat, the painting is shrouded in purples and dark blues, enhancing a mood of despair. Delineating tired muscles and bent bodies with sinewy strokes illuminated by firelight, Law’s crew resembles gutted candles. Jack Nichol employs a similar treatment of the human figure in his portrayal of hopelessness in Normandy Scene, Beach in Gold Area. In subsequent paintings, Law returned to the more impersonal approach to figure use, similar to that of Paul Nash and A.Y. Jackson’s soldiers of the First World War – bit players in the larger scheme of things.

Canadian Tribal Class in Action is another painting from Law’s post-Ostend period. Dark, and, at first glance, peaceful, the painting depicts the deadly night action of 25/26 April 1944, when Canadian Tribal class destroyers RN ships engaged three German destroyers off France, sinking one of them. During the battle, the HMS Black Prince put up a star shell, exposing the retreating Germans as they raced for safety. According to Law, the evening was hardly peaceful as the Allied destroyers closed in and opened fire. “They had quite a battle that night with the German destroyers. They drove one up on the rocks... It’s very hard to paint night actions... star shells coming down... you felt naked when they put them up over you in a torpedo boat,”33 he wrote.

Within nine months34 Law, rejuvenated, was back to using his familiar bold style and vibrant palette. Windy Day in the British Assault Area shows his beloved MTBs, white plumes astern, riding herd on a slower moving assault force on D-Day. His especially lively palette of blues and yellows, coupled with powerful diagonals and broad sweeping strokes, energize the tiny Canadian ships as they boldly cut through the surging sea towards HMS Scylla – the Royal Navy Coastal Force Command and Control ship.35 “On and on skimmed the saucy MTBs, creating plumes like the spread tails of haughty peacocks, and leaving wakes like the powerful wings of seagulls”36 wrote Law.

Conclusion

Although brief, Law’s period as an official war artist generated 29 canvasses and 75 oil sketches. Dramatically exceeding the Canadian War Artists Committee requirements, Law’s work certainly did justice to the historical record, and, as works of art, his renderings are worthy of exhibition anywhere. Like A.Y. Jackson’s Houses at Ypres, his Destruction of Old Chelsea Church (London), 1945 attests to the skill and talent of an artist to filter out adversity in order to portray beauty in the most horrific subjects and conditions. Ironically, despite his productivity during the war, Law felt that he had lost five years of professional development as an artist,37 and, as a result, chose a naval career with the RCN permanent force after demobilization. A remarkable trait of Tony Law was his deep commitment to Canada. When given the opportunity in 1943 to join the Canadian War Records Programme38 on a full-time basis, he declined, feeling that he could better serve his nation at war as a combatant.

In the post-war era, the Nazi menace was replaced by a new threat to world peace as the Soviet Union grew in military power. Working closely with NATO Allies in the Atlantic and Pacific during the Cold War, the RCN stood watch over the surface and subsurface fleets of the Soviet bloc. Law kept up with his painting, garnering the label, “the painting commander”39 while at sea, now scouring the North Atlantic for Soviet ships. In essence, he returned to his status as an unofficial war artist as he recorded this period of an unofficial war.

After retiring from the Royal Canadian Navy in 1966 at the rank of commander, C. Anthony Law quickly became part of the Canadian art landscape, and he was appointed artist-in-residence at Saint Mary’s University in 1967. Bernard Riordon40 said of Law’s post-war work: “His paintings have provided us with a vision of Nova Scotian and Canadian landscape in vigorous and bold realism. In the tradition of the Group of Seven, his works demonstrate a distinctive Canadian point of view by their fresh and robust approach to landscape and by their honesty of purpose.”

Commander Tony German described Law as a “small, soft-spoken and thoughtful man”41 possessing the requisite qualities of “quick thinking, innovation and leadership”42 to take men into battle. This characterization perhaps best describes Law’s life in general. Passionate about painting until the end, Tony Law passed away on 14 October 1996 at his home in Williams Lake. “I don’t need a tombstone,” he told his family and friends. It’s all up there on the walls.”43

![]()

Pat Jessup is the Community Relations Officer/Public Affairs Officer at Maritime Forces Atlantic. She is also a graduate student at Saint Mary’s University, focusing on naval war art during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Notes

- The number of billets was increased to 32 later on in the programme, with six eventually dedicated to the navy.

- Annex B, Canadian War Artists Committee, Instructions for War Artists.

- Grant MacDonald, Sailors (Toronto: Macmillan, 1945), p iii

- Conversation with the artist’s wife, Mrs. Jane Law, 11 July 2004.

- http://www.mcmichael.com/, (McMichael Gallery website) Barbeau was a strong proponent of the Group of Seven and nationalistic art.

- Exhibition catalogue: C. Anthony Law: A Retrospective. Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, 12 May – 25 June 1989, Bernard Riordon, C. Anthony Law, a Retrospective.

- Varley had been an official war artist during the First World War under the federal government’s Canadian War Memorials Fund as well as member of the Group of Seven.

- Exhibition catalogue: C. Anthony Law: A Retrospective. Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, 12 May – 25 June 1989, Bernard Riordon commentary.

- http://www.canadianclubny.org/. Considered the most prestigious Canadian art award and given by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Jessie Dow Prize is awarded for excellence of work in oil and watercolour.

- http://www.civilization.ca/cwm/artists/schaefer1eng.html.

- Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, Percyval Tudor-Hart, 1873, Portrait of an Artist (London: Macmillan, 1961), pp. 228-232

- Ibid., p. 230

- Members of the RCNVR had no post-war commitment to Canada, and could return to civilian life after the cessation of hostilities.

- The E-Boat was the German equivalent of the British MTB.

- http://www.forces.gc.ca/admfincs/subjects/cfao/018-27_e.asp Canadian Forces Administration Order 18-27 Mentioned in Dispatches. A Canadian military honour, awarded by the sovereign, recognizing valiant conduct, devotion to duty or other distinguished service. Law’s 31 March 1942 citation reads: “For daring and resolution while serving in H.M. torpedo boats in daylight attacks at close range, and against odds, upon the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Prinz Eugen..” Bernard Riordon, from the artist’s files.

- David J. Bercuson and J.L. Granatstein, Dictionary of Canadian Military History (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 114.

- It was through persistent lobbying by A.Y. Jackson, H.O. McCurry, and Vincent Massey of MacKenzie King’s government that the Canadian war art programme of 1943 came into being. Prominent Canadian artists, anxious to participate in a similar Canadian programme, were outraged at the indifference displayed by the government during the first three years of the war. Comfort, Charles et al Canada at War, A Symposium on Art in War Time (Maritime Art, No. 3, February-March, 1942) pp. 83-92

- Laura Brandon, Canadian Military History, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring 1997, p. 100, National Gallery of Canada Archives, Correspondence with War Artist, 5.42.L, Copy in Canadian War Museum Artist File, Anthony Law.

- Brandon, p. 99.

- Marc Milner, Canada’s Navy: The First Century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), p. 144.

- http://www.readyayeready.com/dday/page2.htm. An estimated 230 enemy surface ships were in the Channel area, including 16 destroyers, 50 E-boats, 60 H-boats, armed trawlers, minesweepers, and so on. In the four months ending on 23 August 1944, the 10th Flotilla sank 35 surface vessels, including four destroyers, and damaged 14 others.

- http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/general/sub.cfm?source=collections/ cmdp/mainmenu/group01/dsc. The Distinguished Service Cross was awarded to naval officer and warrant officer personnel for the performance of meritorious or distinguished services before the enemy.

- Dean F. Oliver and Laura Brandon, Canvas of War (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2000), p. 123.

- White Plumes Astern is illustrated with several examples of Law’s sketches.

- Conversation with Mrs. Law 11 July 2004. Tony Law was a tireless artist, who, in his later years, could produce a painting a day. He worked in a large-scale format, quickly, and primarily with a palette knife, leaning towards the abstract. Dispensing with working drawings, Law preferred to work directly on canvas.

- The Toronto Telegram, 20 June 1942.

- Barry Lord, The History of Painting in Canada, Toward a People’s Art (Toronto: New Canada Publications, 1974), p. 186. During the inter-war years, an interest in portraiture arose among the social-realist and mural painters. An example is Miller Brittain’s, Saint John Hospital mural cartoons.

- The Quebec Chronicle-Telegraph, December 1943.

- Conversation with Mrs. Jane Law, 11 July 2004.

- Brandon, p. 99.

- War Art handout, 29 July 2004.

- Riordon commentary, p. 9.

- Oliver and Brandon, p. 113.

- Conversation with, Mrs. Jane Law, 25 July 2004.

- The MTB captains met on board Scylla daily to plan the night’s operations. Tony Law, White Plumes Astern (Halifax: Nimbus, 1989), p. 74.

- Ibid., p. 69

- Conversation with Mrs. Jane Law, 11 July 2004.

- http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/newsroom/view_news_e.asp?id=1261. At the conclusion of the Second World War, the Canadian War Records Programme was discontinued, and until 1968, when the Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Programme was introduced, Canada was without a sanctioned military art programme. On 6 June 2001, the Canadian Forces Artists Programme was implemented “to enable artists from across Canada, working in a variety of media, to capture the daily operations, the people, and the spirit of the Canadian Forces, and in so doing give the Canadian public a lasting record of our military men and women and their work.”

- While serving in the aircraft carrier HMCS Magnificent, Law formed an art class among the crew that affectionately became known as “Maggie’s Drawers.” The Ottawa Journal, 23 October 1952, reported that an exhibition at Zwicker’s Gallery in Halifax of “Maggie’s Sea-going Artists” was well received. Conversation with Mrs. Law and Ian Muncaster, Zwicker’s Gallery.

- http://www.twrsoft.com/ross/tony01.htm. Bernard Riordon, former Director of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and current Director of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton chaired Law’s Retrospective Exhibition at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in 1989.

- Tony German, The Sea is at Our Gates, The History of the Royal Canadian Navy (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999), p. 166.

- Ibid.

- Bill Twatio, “A Sailors Legacy, C. Anthony Law (1916-1996),” Esprit de Corps, Volume 5, Issue 10, p. 11.

50+Years

Canada and Peacekeeping

history, evolutions and perceptions

L’université d’Ottawa University

11-14 May 2006

Canada and Peacekeeping

What it’s been, what it’s not been and what it could be.

The Organization for the History of Canada, the Royal Military College, The University of Ottawa, Carleton University, The Canadian War Museum, The United Nations Association in Canada, and The Department of National Defence present a Conference to mark the 50th anniversary of Canadian Peace Operations

For more information please contact Alex Morrison: sandym@mail.com or visit: www.orghistcanada.ca

Keynote speakers: Ambassador Allan Rock, General Richard Hillier, LGen (ret’d) Roméo Dallaire, Alex Morrison, J.L. Granatstein, Jacques-Paul Klein, Robert Jackson, and Sir Marrack Goulding