This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

Leadership and Responsibility in the Second World War

Edited by Brian Farrell

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press 2004. 273 pages, $27.95 (paperback)

Reviewed by Lieutenant-Colonel Rory G. Kilburn

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Sub-titled Essays in Honour of Robert Vogel, Leadership and Responsibility in the Second World War is a series of essays addressing the actions and decisions of wartime leaders and their concomitant accountability. Written by colleagues and former students of the late Vogel, a history professor at McGill University, the collection is a tribute to his passion for studying British military and political history – especially the period between the First and Second World Wars and the Second World War itself. The book embraces the periods with which Vogel was so fascinated, but with a twist. Rather than concentrating exclusively on heroic leaders or military officers, it explores the actions of the British politicians and their advisors during the events that led to the war in Europe. For the military reader, it also explores leadership and responsibility on the part of military leaders during three very different campaigns during the Second World War.

Sub-titled Essays in Honour of Robert Vogel, Leadership and Responsibility in the Second World War is a series of essays addressing the actions and decisions of wartime leaders and their concomitant accountability. Written by colleagues and former students of the late Vogel, a history professor at McGill University, the collection is a tribute to his passion for studying British military and political history – especially the period between the First and Second World Wars and the Second World War itself. The book embraces the periods with which Vogel was so fascinated, but with a twist. Rather than concentrating exclusively on heroic leaders or military officers, it explores the actions of the British politicians and their advisors during the events that led to the war in Europe. For the military reader, it also explores leadership and responsibility on the part of military leaders during three very different campaigns during the Second World War.

Leadership and Responsibility in the Second World War is divided into three parts: the statesmen and politicians; the bureaucrats and the diplomats; and the military commanders. The first two sections explore the pre-war and early-war years, while the section on military commanders looks at three specific wartime events involving uniformed services. The first essay, written by Vogel himself, is a study of Neville Chamberlain and the British policy of appeasement. It clearly shows Chamberlain as the driving force behind this policy, and it discusses his failure to prevent war. The second essay in this section is a discussion of the actions of the “Old Tories” – a group of backbenchers who acted as strong and uncritical supporters of the Government policy of appeasement, and then strong but critical supporters of the Government’s efforts to prepare for war. The final essay here deals with what is, in my view, the antithesis of the heroic leader, Clement Atlee, and the events that prepared him for his role in the coalition government war cabinet during the war.

The second part of the book comprises two essays on the bureaucrats and the diplomats. The first essay in this section looks at British war scientists and their politicking, and ultimately concludes that ‘throwing great gobs of money and talent’ at a problem does not necessarily guarantee the desired outcome in war. The second essay describes Sir William Seeds and his ill-fated attempts to forge an alliance with the Soviet Union. While discussing Seeds’s role in the diplomatic offensive, the author ultimately blames Chamberlain’s Government for the failure, and this constitutes an interesting bridge to the book’s first essay.

Due to the structural compartmentalization of the book, and the short length of the essays contained therein, the text is a relatively easy read. The first five essays concentrate on events leading up to the war, then the early months of the war. This makes for interesting reading, because the reader can pull out the parallels from the various selections and understand the strategic thrust of the government – whether or not one agrees with the conclusions reached by the authors of the various essays. Because of the different actors involved in the same time period, readers can draw parallels between Britain’s desire to maintain the status quo as a world power through comprehensive disarmament, and other nations’ willingness to use violence to destroy that status quo.

The extensive footnoting makes this volume quite useful for scholars who wish to further explore the theses and events portrayed in the book, especially those who may wish to study the relationship between effective leadership and the acceptance of responsibility for one’s actions and decisions. Military officers who wish to further study leadership, and the place of technology and science in war fighting, can use the book as a springboard to more focussed research.

The greatest weakness of the book is the disjointed time continuum of the third section. Covering military commanders during the war years, the first essay looks at the German Colonel Claus, Count von Stauffenberg and the attempted assassination of Hitler from the viewpoint of the German military ethos. The second essay explores the decisions of Field Marshal Earl Wavell and the fall of Singapore, while the final essay discusses General Harry Crerar and the tension that existed between coalition aims and national aims during the Normandy campaign. This section covers three very different time periods, three different armies, and two very different campaigns, and it does not address the decisions made by the politicians and advisors in the earlier sections. Although the theme of the volume is Leadership and Responsibility, it is very difficult for the reader to understand the parallels in such disparate situations.

This is not to say that the last section is not without merit – especially for military professionals. The final essay is extremely interesting for Canadian military officers, because it discusses the tensions of the dual accountability placed upon commanders when national aims and coalition aims diverge. This chapter should be a ‘must-read’ for Canadian commanders and staffs participating in coalition operations. It can prove useful as a ‘lessons-learned’ vehicle for coverage of the pressures generated from both coalition military commanders and a national government, and how to balance these often competing priorities, or, if necessary, to embrace one at the expense of the other.

Furthermore, the essay on von Stauffenberg and his rationalization of the need for the military to act to remove Hitler from power can form the basis of an extremely interesting discussion on the principle of military subordination to civilian authority. “Senior commanders had a responsibility to the soldiers, the people, and the nation – an ‘overall responsibility’ that superseded mere military obedience.” As members of the profession of arms, Canadian military professionals would do well to explore and compare the values of other militaries to their own, to better understand their profession and their responsibilities to the people they serve. Even if the book were only to start that discussion, the essays contained in Leadership and Responsibility in the Second World War will have fulfilled their intended purpose.

![]()

Lieutenant-Colonel Kilburn is Senior Staff Officer Non-Commissioned Member Professional Development at the Canadian Defence Academy.

CMJ collection

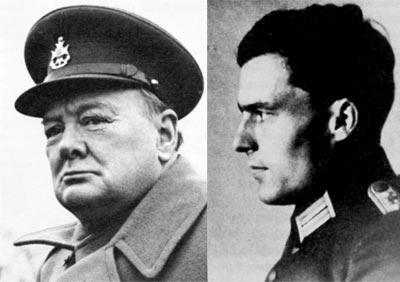

Winston Spencer Churchill (left) and Claus, Count von Stauffenberg (right).