This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Canadian Forces Transformation

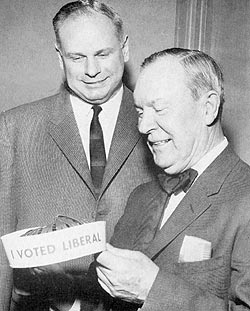

DND photo CFC66-11-3

The Honourable Paul Hellyer, Canada’s Minister of National Defence, 1963-1967.

From Minister Hellyer to General Hillier: Understanding the Fundamental Differences Between the Unification of the Canadian Forces and its Present Transformation

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

The April 2005 release of a new Canadian defence policy statement, hereafter referred to as the 2005 Defence Policy, has planted the seeds for a major transformation of the Canadian Forces (CF) in the coming years. Since its release, there has been a sense that both the focus and intentions of the new policy are similar to those of then Minister of National Defence (MND) Paul T. Hellyer and his 1960s desire to create a unified Canadian military capable of providing the government greater flexibility.1 Prime Minister Paul Martin’s statement in the 2005 International Policy Statement (IPS), advocating a need for a “fundamental restructuring of our military operations ... to make certain that in time of crisis, Canada’s military has a single line of command and is better and more quickly able to act,” is quite analogous to Minister Hellyer’s 1964 statement that the “proposed unified force will provide much greater flexibility to meet changing requirements.”2

The CF vision outlined in the 2005 Defence Policy, elaborated upon in recent months by the new Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), General R.J. Hillier, speaks of integrated forces and a unified command structure and system.3 However, terms such as ‘integration’ and ‘unification’ at National Defence have come to be associated with the 1960s and Minister Hellyer, and, because of the enduring negative connotations associated with that unification process, they have tended to be scrupulously avoided at National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ) over the years.4 With terminology in the new CF vision resonating with ideas espoused by Minister Hellyer in the 1960s, it may be tempting, at first glance, to liken the unification initiative of the 1960s to the current CF transformation, and even to speculate that this transformation may be the last chapter of the unification journey launched by Minister Hellyer.

DND photo RE66-1426

Canada’s first Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) after unification, Air Chief Marshal Frank R. Miller, CDS from 1964 to 1966.

Nonetheless, any such argument could only be based upon superficial analysis and a very broad interpretation of context and defence policy intentions of both periods. As this article will suggest, comparing the CF unification and the CF transformation is misguided.5 Indeed, the context of the two periods, the ideas and the principles underpinning both initiatives are fundamentally different. In addition, the implementation strategy chosen by the new CDS to realize this transformation is not comparable to the one adopted by Minister Hellyer to guide the unification of the CF in the 1960s. The 2005 Defence Policy, the new CF vision and the CF transformation are not intended to be the final chapter of Minister Hellyer’s unification scheme.

This article will review Paul Hellyer’s ideas and his strategy to achieve unification of the CF, and then compare them with the 2005 CF transformation process. The first section will provide an overview of the context of both periods, and outline the main ideas behind the development of the 1964 and 2005 defence policies, including brief perspectives on the two main individuals charged with their implementation, Minister Hellyer and General Hillier. It sets the stage for an examination of the implementation strategies of unification and transformation by analyzing and comparing the sequencing and phasing of the major change activities selected to advance the present initiatives. The last section will draw from the lessons of the unification of the CF to offer recommendations for CF transformation.

Context and Ideas

Statements expressed in policy documents, such as the 1964 White Paper and the 2005 Defence Policy, are invariably the outcome of dominant ideas, which, in turn, may affect significantly the status of authoritative individuals, the organizations and the associated decision-making processes.6 When Minister Hellyer decided to reform Canada’s armed forces drastically in the early 1960s, his ideas had been strongly shaped by the political environment of the times. As a result, he opted to make significant changes to the strategic decision-making processes at National Defence, to the structure of the national headquarters, and to the organization of the field commands, with the clear expectation that Canadian defence matters would be improved.

Minister Hellyer and the Unification of the CF

Minister Hellyer arrived at National Defence in 1963 with a clear mandate to reform Canadian defence. By the time he left in late 1967, he had, in all likelihood, made the most significant and far-reaching changes to defence administration in Canada since 1923.7 A series of events had taken place during the period 1957-1963, while Minister Hellyer was the defence critic for the Liberal opposition, that convinced Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson that significant changes at Defence were required. In addition, the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and the concomitant response of the Canadian armed forces, when “control of the armed forces passed briefly out of the government’s hands,”8 was undoubtedly a determining factor that helped to convince the government that the command structure of the military had to change. And perhaps, it was “the catalyst that led the Pearson government to proceed with unification in 1964.”9

The main challenge facing Minister Hellyer, as he crafted the 1964 White Paper, was not a military threat specifically, but rather, the increasing cost of defence for a government facing a fiscal crisis, and, by then, becoming more inclined to spend on national social programs than on defence.10 For the federal government, there had been a series of large deficits and the level of national debt was increasing. With statutory expenditures on the rise, and defence expenditures representing the largest portion of non-statutory and controllable expenditures, the defence budget was clearly a target for reductions. Minister Hellyer recognized this as he was developing the 1964 White Paper. As he stated, “[t]he impact of sharply rising costs for personnel, maintenance, and operations had been observed for some time, and its consequences for Canada’s defence were strongly emphasized in the policy discussions of 1964.”11 The government’s deficit had increased by 21 percent between 1961/62 and 1963/64, and, as the largest controllable or discretionary component of the government’s budget, the defence allocation was being reduced by 10 percent between 1963/64 and 1964/65.12

Minister Hellyer was also very much influenced by the report of the government-appointed Royal Commission on Government Organization, mandated to review, in the interest of managerial efficiency, the organization and methods of the federal government.13 He relied to a great extent on the conclusions of this commission, “which had done such a splendid job of exposing the waste and extravagance resulting from duplication and triplication.”14 One defence analyst specializing in Canadian defence administration argues that the work of the commission was important because it “was to provide the authority and validity to concepts that others [such as Minister Hellyer] would champion later.”15 Consequently, the new minister of defence had strong views about the need for a comprehensive review of defence policy, and for the integration of the command structure of the armed forces to streamline the organization and to reduce the problems of tri-service inefficiencies.16

White Paper on Defence, released in March 1964 by a new Liberal government, was an important document for several reasons. Most notably, “it was an attempt to build a defence policy on a Canadian foundation,”17 and it proposed a unified force to provide the necessary flexibility to meet changing defence requirements. While the roles outlined for the CF in the 1964 White Paper were essentially the same as those expressed by Minister Brooke Claxton in a statement to Parliament in 1947, the 1964 Defence Policy – like the 2005 Defence Policy – ‘re-established’ the defence of Canada as the first priority for Canada’s armed forces.18 In order of priority, the roles were: defend Canada, defend North America, and participate in international operations of choice. In essence, these constituted two strategic imperatives and one strategic choice.19 The 1964 White Paper did not contain detailed tasks for the CF. In fact, the policy was clear in its intention not be specific, concluding that “no attempt has been made to set down hard and fast rules for future policy and development... The paper is a charter, a guide, not a detailed and final blueprint.”20 This left the government, and, more specifically, the Minister, the flexibility to make adjustments as circumstances dictated, and to proceed toward unification of the CF with few constraints imposed by policy.

DND photo REP68-758

Frank Miller’s successor as CDS, the highly decorated General Jean Victor Allard, who served in the position from 1966 to 1969.

Minister Hellyer also strongly believed that the mechanisms of civil control of the Canadian military needed a major overhaul, and that this was best achieved through a centralization of the control and administration of the CF into one Chief of the Defence Staff, instead of three service chiefs reporting independently to the minister. Under Minister Hellyer, therefore, there would be one integrated Canadian defence policy, one overall defence program, one CF Headquarters (CFHQ), and one Chief of the Defence Staff with authority over the three service chiefs.

But Minister Hellyer had more change in mind for Canada’s military forces than just headquarters restructuring. On the heels of the Glassco Commission, he viewed a major reorganization of the defence forces as the only means to make resources available for future capital equipment acquisitions. He was convinced that the establishment of a streamlined bureaucracy, and the modernization of defence management methods, would help in achieving the desired economies. He explained that if Canada had to maintain useful forces to meet its national and international commitments, there were only two choices open to the government: “We had to increase defence spending or reorganize our forces. The decision was to reorganize.”21 The solution was complete integration of the services – unification.

DND Photo

Paul Hellyer and Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson enjoyed a close working relationship.

There was definitely a recognized difference between integration and unification – with integration seen as a precursor to unification. Air Marshal F.R. Sharp, Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, clarified this distinction in his testimony to the Parliamentary Defence Committee in 1967:

In the minds of some, integration and unification have been regarded as alternatives; in the minds of others two separate and easily defined steps in a process – two steps that were so distinct that there were no or little overlap between the two. Neither of these definitions is correct – except in a purely legislative sense. Integration of the three services began when the National Defence Act was amended in 1964, creating one chief of the Defence Staff and abolishing the three separate chiefs of staff positions. Unification will become a legislative fact if the National Defence Act is amended to create one service in lieu of the present three services.... it is difficult to define precisely where integration ends and unification begins. The whole process is a continuous complex programme of interwoven steps.22

By late 1966, Minister Hellyer had created, through Bill C-90, the office of the CDS, which centralized decision-making, and he had changed the field command structure, creating six functional commands in lieu of the three services’ eleven subordinate headquarters. He had also achieved considerable reduction in duplication and triplication of facilities and services. In spite of this progress, he was not satisfied with integration. Service resistance to his integration efforts convinced him that only unification of the services would truly institutionalize the changes he was seeking, and would help develop “a sense of purpose and a sense of belonging to one single Service.” To Minister Hellyer, unification was “the end objective of a logical and evolutionary progression,”23 resulting from the integration of staffs and headquarters, and “this [integration] will be the first steps toward a unified defence force for Canada.”24 Unification remained the best way to pursue his objective of reducing overhead costs, realizing greater administrative efficiency, and achieving bureaucratic control of the military.25

There is no indication that Hellyer was concerned about the potential adverse impact that the administrative centralization he was proposing would have on the operational effectiveness of the various CF components. While he indicated that the “White Paper of 1964 would not have recommended integration ... if we had not been certain of the improved capacity of a unified force to meet the demands of modern warfare,”26 operational effectiveness was not a priority of his defence restructuring. Air Marshal Sharp elaborated upon what Minister Hellyer intended to accomplish in unifying the forces by outlining the primary aims of unification, indicating they “were to be accomplished, of course, without decreasing operational effectiveness during the process.”27 Canadian historian David Bercuson contends that “[t]he creation of a truly effective fighting force did not figure in the government’s agenda.”28 In fact, besides achieving cost savings, modernizing management methods and improving efficiency, Minister Hellyer was also more interested in unification as a means to “broaden the opportunities available to service-motivated and expensively trained personnel,”29 reflecting, in many ways, his own frustrating wartime experience with the services.

When he arrived at National Defence in 1963, Minister Hellyer was 40 years old, had been a Member of Parliament (MP) since 1949, and had hopes that his achievements at National Defence would help him become an obvious choice to succeed Lester Pearson. As military historian Desmond Morton remarked, Minister Hellyer was “an aggressive man with few of the gentler political graces.”30 Yet, he was ambitious, and to bring about the changes he wanted at defence, Minister Hellyer had to act quickly. And act quickly he did.

General Hillier and the CF Transformation

In recent years, military analysts and senior officers have recognized the need for a new vision to guide the CF in meeting the defence and security challenges of the 21st Century, especially the asymmetric threats posed by terrorism and failed or failing states. The previous CDS, General Ray Henault, had clearly recognized that fundamental changes to the CF were necessary in order to better position the institution for the coming decade. Transformation and change were the main themes of the last two CDS Annual Reports to Parliament, with General Henault acknowledging in 2004 that if the CF “were to remain relevant, we needed to accelerate our [transformation] efforts and make difficult choices. Those choices are now more urgent than ever.”31 However, transforming the CF without the benefit of a new defence policy, without an overarching CF vision, and with a limited budget, proved to be near impossible. Consequently, little progress could be made in this regard during General Henault’s tenure. The arrival of General Hillier as CDS in February 2005, and the release of a new defence policy, would provide the long-awaited opportunity.

Unlike the 1964 White Paper, which had few specifics, the 2005 Defence Policy contains a comprehensive list of tasks for the Canadian military, a continuation of a practice that began in Canada with the 1992 Canadian Defence Policy statement.32 Prior to the 1990s, defence policy statements tended not to specify detailed tasks for the CF, but rather included broader statements of intentions that would not reduce the government’s flexibility of action. While it is evident that more specificity in the defence policy is advantageous to military planners – it provides the clarity necessary to develop plans and capabilities to meet the assigned military tasks – it remains that such an approach tends to commit the government to more limited courses of action in the development of future force structures. In addition, it can expose the government to criticism when funding projections do not materialize, or when circumstances require a change of policy, as was the case in the years after the release of the 1987 Defence White Paper Challenge and Commitment.

At the broadest policy level, the 1964 White Paper and the 2005 Defence Policy are very similar. Both policies are strongly connected to foreign policy, and articulate similar roles for the Canadian military. While the 1964 White Paper stresses that the objectives of Canadian defence policy cannot be dissociated from foreign policy, the 2005 Defence Policy is an integral part of the Government’s International Policy Statement, rather than a separate government white paper. Similar to the 1964 policy, the 2005 Defence Policy is clear that “[T]he Government believes ... that greater emphasis must be placed on the defence of Canada and North America than in the past,” indicating an important shift of priority for Canadian defence.33

DND photo

The Honourable William C. Graham, PC, QC, MP, Minister of National Defence in the Paul Martin Liberal government.

The 2005 Defence Policy, which advocates a prominent role for Canada’s military as part of the Canada’s international policy, provides the foundation for change that the CF leadership was seeking. The CF vision, which has been incorporated in the 2005 Defence Policy, and the necessary concomitant CF transformation, aim at fundamentally reorienting and restructuring the functions and the command and control of the CF to better meet the emerging security demands at home and abroad.

General Hillier strongly believes that for the CF to achieve greater operational effects in Canada and around the world, it will need to assume a more integrated and unified approach to operations, which can only be achieved through a major transformation of the existing command structure, the introduction of new operational capabilities, and the establishment of fully integrated units capable of a high-readiness response to foreign and domestic threats.34 One defence analyst believes that “Canada’s future defence policy and military capabilities have now been defined by the appointment of Gen. Rick Hillier as chief of the defence staff and by the significant, multi-year defence budget announced by the federal government.”35

Minister Hellyer’s primary reason for initiating changes to the CF in the 1960s was centred upon achieving greater efficiencies, to create economies that could be directed toward capabilities. In contrast, General Hillier’s ideas are clearly focused on improving operational effectiveness. The mere fact that there is no mention of objectives, such as “controlling defence costs,” “improving management methods,” and “creating efficiencies” in the 2005 Defence Policy is quite revealing, and, clearly, indicative of the type of dominant ideas that shaped the writing of this defence policy.

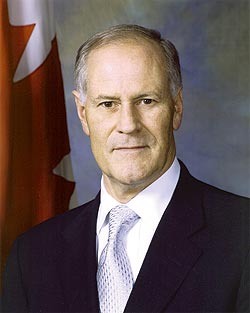

DND photo

General R.J. Hillier, CMM, MSC, CD, Chief of Defence Staff.

The domestic political environment for the 2005 Defence Policy is one where the Government is running a budget surplus, and the defence budget is being substantially increased. “In Budget 2005, the Government made the largest reinvestment in Canada’s military in over 20 years, totalling approximately $13 billion.”36 The announcement by the federal government in the spring of 2005 of significant multi-year increases to the defence budget – which includes an expansion of the CF by 8000 personnel – serves to reinforce the point that this CF transformation is driven by different dominant ideas than was unification in the 1960s.37

General Hillier’s concept and implementation strategy will mean important changes to the structure of the CF in the coming years, and it is expected that these will not be accepted unanimously within the defence community, notwithstanding the pressing and well-founded operational imperatives underlying these changes. Initiatives of this magnitude create anxiety, foster rumours and generate suspicion, as options for change are being developed and important decisions are often made at a speedy pace, without the usual full consultation expected by some of the actors. Large-scale changes in organizations tend to generate strong resistance, as power shifts from one group to another. Consequently, if there is likely to be one strong similarity between Minister Hellyer’s and General Hillier’s initiatives, it will be in the intrinsic passive resistance of the defence establishment to rapid changes, placing even more importance upon adopting the right implementation strategy.

Large-scale Changes at Defence

An assessment of the implementation strategies of the integration and unification of the CF in the 1960s, and the CF transformation in 2005, is critical to understanding why there are strong differences between the two initiatives. Both Minister Hellyer and General Hillier made the deliberate choice to “turn up the urgency,” and to move aggressively to implement the defence policies, allowing for interesting comparisons between the two implementation strategies.38

Considering the size of the Canadian National Defence organization, completing the integration process and passing unification into law in less than four years was a daunting task for Hellyer. Similarly, while the 2005 Defence Policy is not explicit about timelines for the CF transformation, General Hillier has made it abundantly clear that he is committed to a very aggressive CF transformation implementation strategy, moving as fast as is possible to initiate many important command structural changes to the Canadian Forces. He has indicated, on several occasions, that he wishes to complete the majority of restructuring envisaged for the CF during his tenure as CDS, expected to last from three to four years.39

If one compares the relative failure of the earlier integration efforts of previous ministers of defence with the ‘success’ of Hellyer’s 1964-1968 venture, a number of important differences stand out.40 First, the 1964 integration was achieved by beginning with the top of the defence structure and then working progressively down the chain of authority between 1964 and 1968. Barely two weeks after the White Paper was presented to the Commons, Bill C-90, the Integration of the Headquarters Staff Act, generated to amend the National Defence Act (NDA), to replace the individual service chiefs with one Chief of the Defence Staff, and to create the Defence Council for oversight and consultation, was introduced. Because the three existing services were legal entities, Hellyer had to proceed through Parliament to initiate the process of integrating the headquarters. Nevertheless, this step did not deter him, and he moved swiftly. Bill C-90 was passed in early July and came into effect on 1 August 1964, at which time the three service headquarters were integrated into one CF headquarters, comprised of functional branches. Once “the top was integrated, the momentum for change could not so easily be halted or the commitment to integrate reversed.”41

Second, unlike earlier integration attempts, which were “characterized by their haphazard nature,”42 where arguments were weighed to determine the merit of integrating a function, this time it was more a matter of successfully implementing a predetermined government policy. Thus, after integrating the headquarters, Hellyer used his authority as minister to direct the reorganization of the field command structure into six functional commands. By August 1966, the integration process that had started on 1 August 1964 was almost complete. Permanently disbanding the three services required another bill in Parliament, which was initiated with the tabling in late 1966 of Bill C-243, the Canadian Forces Reorganization Act.

Hellyer nevertheless faced major roadblocks on the way to unification. The requirement to enact bills in Parliament forced him to account to parliamentarians and to the official Opposition Party regularly and publicly with respect to his integration and unification plan. Between 1964 and 1967, Members of Parliament met in special committees and debated both Bill C-90 and Bill C-243 for days, hearing evidence from many witnesses.43 As opposition to unification grew in 1966 and 1967, and senior officers started to opt for retirement, rather than implement what was, for all intents and purposes, complete unification, suspicion and resentment of Minister Hellyer grew within the Parliamentary Defence Committee.44 The potential for the marginalization of the history, identity, pride and traditionalism of the three services that unification would provoke was thoroughly exploited by the Opposition and the press to create sensationalism, and to distract Minister Hellyer. Even though he had publicly stated on many occasions that the essential traditions of the services would be maintained, he constantly faced stiff resistance to his ideas. In the end, Bill C-243 was debated in 74 sittings of the Defence Committee in 1967, and the Government had to set a limit on debate in the House in order to get final passage of the Bill in April 1967.

In contrast to Minister Hellyer’s strategy for integration and unification, which initially targeted the top of the defence structure, General Hillier’s CF transformation of the CF command structure is beginning at the ‘middle’ of the command structure, at the operational level. It is not aimed at restructuring NDHQ, but is focused upon the most important point of change for this transformation. “Operational effectiveness, and in particular operational command, is at the heart of the transformation agenda.”45

General Hillier’s immediate focus is on initiating the introduction of new military capabilities, and on establishing a more robust and more operationally focused CF command structure. While the development, acquisition and introduction of new major equipment will certainly take years to be completed,46 the changes to the CF command structure can occur much more rapidly. General Hillier moved quickly to seek the Minister’s endorsement to announce the creation of Canada Command (CANCOM), Canada Expeditionary Command (CEFCOM) and Canada Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM). The implementation of the command structure organizational changes envisaged by the CDS does not require amendments to the NDA: the MND possesses the executive authority, without the need to consult Parliament, to approve the formation of new commands. General Hillier’s immediate focus is on establishing a more robust and more operationally focused CF command structure. Unlike Minister Hellyer who radically transformed the structure of the national headquarters, the CF transformation will initially entail minimal changes to the structure of NDHQ, except for the creation of a strategic joint staff (SJS) to assist the CDS in his role as strategic commander and senior military advisor to the Government.47 Finally, unlike Minister Hellyer, who was seeking more centralization at the top to create efficiencies, General Hillier has promised to be guided by a mission-command leadership philosophy, and is determined to decentralize the execution of operations.48

Potentially the most contentious element of this CF transformation in the year ahead will be the determination of the future roles of the Environmental Chiefs of Staff (ECSs), the heads of the army, the air force and the navy. In 2006, Canada Command will assume responsibility for routine domestic operations that are currently conducted by the ECSs, and it will assume operational control of all CF military capabilities. Further, the integration of military capabilities to create a high-readiness force that will operate by engaging as a whole under command of new operational commanders, such as the Standing Contingency Task Force, and the progressive shift of the command structure from one that is presently environment-centric to one that will be more unified, may have important implications for the ECSs. The CF transformation is in its early stages, and it remains to be decided what residual force generation functions the environments will retain in the new CF command construct. One thing seems almost certain, however, even at this early stage of the CF transformation: ECSs will have less authority in a transformed CF as General Hillier strives to create a greater CF identity, and shift power and influence to the new operational commanders.

While Minister Hellyer’s ideas of integration and unification have been highly criticized over the years, he would have probably “fared better in the history books” had it not been for his single-minded drive and the approach he employed as he wrestled with an entrenched defence bureaucracy. Minister Hellyer created an atmosphere of suspicion, and his senior military advisors were seldom consulted as he developed his unification ideas. “Most senior officers heard about the latest [unification] development through press releases.”49 While Minister Hellyer initiated several studies to provide a foundation for the 1964 White Paper soon after taking over as minister, “true to his modus operandi [he] made no plan or organizational model”, and left his senior military staff in the dark about his ultimate plans.

Officers who testified to the Defence Committee, many of them members of the senior staff selected by Minister Hellyer, reported evidence of “mistrust, intrigue, hostility, and confusion in DND and CFHQ [and] ... were asked to write a plan that had no foundation or precedent.”50 It was not until General J.V. Allard was appointed CDS in 1966 that Armed Forces Council was created. This became a forum for the functional commanders to provide the CDS and the MND advice on integration and other military matters. However, the greatest determining factor in progressing integration and unification was probably the personal drive of the Minister, “determined both to impose his will on a very large and complex department and to use it as a stepping stone to higher offices.”51

General Hillier’s approach to executing the CF transformation has some similarities to the implementation techniques of Hellyer, but it also contains important differences. Like Minister Hellyer, the CDS has adopted a CF transformation implementation strategy that focuses upon urgency to change, high and irreversible momentum, and rapid incremental decision-making. General Hillier is not waiting for the development of a master plan to move forward with transformation.52 As he has said several times, he is prepared to assume some risks in certain areas, but he will not compromise ongoing operations. “On the transformation side over this next twelve to eighteen months ... I’m actually pretty comfortable if we can lay it out 75 to 85 percent in detail [and] we can sort out the rest of it on the move.”53 The CF Transformation Team he established in June 2005 – mandated to support him in implementing the command structure transformation, and to coordinate implementation between the new commanders and the ECSs and the Assistant Deputy Ministers – has been asked to use an aggressive but deliberate approach in order to articulate potential options that will optimize outcomes.54

Classic change management suggests that a comprehensive action plan, complete with the many initiatives needed to implement and achieve the plan, is the approach to take to move to a new vision. However, organizations have discovered that in adopting this classical approach, change initiatives can number in the hundreds, and they quickly become unmanageable. With so many initiatives to be implemented, “the energy and focus inside the organization becomes diluted and blurred ... Often, the end result is an ineffective effort, with many initiatives that are never implemented.” The alternative is to find the “single, strategically most important point of change,” that if the organization maintains and aligns focus on it, will change everything else in the organization.55 In the more immediate term, this strategic imperative for the CDS is operational effectiveness, which has been given the necessary thrust with the announcement of the creation of three new operational commands in early 2006.

The challenge in this rapid-development cycle CF transformation is to manage astutely the consequences of the early decisions taken by the CDS and the MND, and then to adjust course by a series of corrective measures along the way, keeping the overall vision and aim in mind. This is definitely a riskier approach, in that not all the higher-order effects of the decisions taken can be predicted in a complex and dynamic organization, such as National Defence. But it is a strategy that is necessary to overcome the bureaucratic inertia that is typical of large governmental organizations. By maintaining a sense of urgency with this CF transformation initiative, the CDS has retained the attention of leaders at all levels, and he has reinforced the belief that this large-scale change cannot wait, and must be actioned with vigour. Recent events, such as the terrorist bombings in London and the Hurricane Katrina disaster in the southern United States, are only fuelling his drive to expeditiously improve the command and control structure for domestic operations.56

General Hillier is convinced that the current transformation initiatives must generate high momentum in order to get people energized and passionate about this particular transformation, and to make people aware of the many opportunities that it offers. It is imperative to create important and irreversible change initiatives that point to a new CF focus, a new organizational framework, and, eventually, a new CF culture. The early nomination of commanders for these commands, and the assignment to each of them of a small implementation team, is another way for General Hillier to generate other transformation “circles of energy,” helping him to move aggressively.57 Remaining consistent with his mission-command philosophy of leadership, new operational commanders are given latitude in developing, based on a broad strategic intent, the concept of operations and the structures for the new commands. That being said, the CDS remains actively engaged in shaping the implementation of the CF vision, and is using Armed Forces Council as his senior military advisory body to help him guide the transformation. As it was for Minister Hellyer and unification, the personal drive of the CDS is an important element behind this transformation.

Learning from Unification

Minister Hellyer’s ideas and his policy of unification generated controversy from the outset, with Hellyer frequently being blamed for subsequent failings of defence policy and the armed forces.58 This is probably unfair, as there were several positive effects of unification. A plethora of tri-service committees was abolished, considerable reduction of facilities and services was achieved, a single CF policy and planning process for the entire Department was established, decision-making was improved with the creation of the office of the CDS, a broader understanding of the tasks and problems of the CF was obtained at the senior levels, and the scope of career opportunities for some support trades and classifications was expanded.59

There were negative effects of unification, stemming largely from Minister Hellyer’s single-minded focus on administrative efficiency. While, in fairness to Minister Hellyer, not all negative aspects were the direct result of unification, many pervasive ideas that constituted the pillars of unification set the pattern for further centralization at NDHQ, and significantly influenced the continued bureaucratization of defence in the 1970s and early 1980s, a trend for which Minister Hellyer is often blamed. Major Charles Cotton, who conducted a study on the cultural consequences of unification in the early 1980s, squarely laid the blame for the growth of a managerial frame of mind at Defence upon unification.60 Reputable defence analysts and historians, such as Douglas Bland, David Bercuson and Jack Granatstein, continue to hold unification responsible for the civilianization of high command in Canada.61

As several studies in the late 1970s and early 1980s have confirmed,62 unification resulted in the considerable loss of single service perspective and expertise, vital to good decision-making, and the CF staff structures created as a result of unification were not suitable to deal with some of the issues facing the individual functional commands. Many changes were done strictly to enhance administrative efficiency rather than operational effectiveness, with ineffective organization and procedures being imposed in the interests of conformity.63 During the 1980s, unification gradually weakened and the three service environments assumed more and more of the old service prerogatives, centred upon the need for them to retain strong influence in all areas of defence.64 Therefore, over the years, many problem areas relating to environment-unique expertise were recognized and corrected.

While General Hillier is embarking on CF transformation with a different focus than that of Paul Hellyer, unification offers many important lessons for today. First, it will be important, as the command structure of the CF evolves in the coming years, to establish the right mechanisms for the three environments to continue to exert influence in areas related to their unique expertise and competence. This discussion is not about single-colour uniforms or century-old traditions: it is about establishing the appropriate distribution of responsibilities between the new operational commands and the ECSs – and it will not be an easy task. It is a critical step to undertake to ensure that overall operational effectiveness of the CF is improved, not reduced.

Second, preserving the positive elements of the ‘warrior’ culture of the three environments, while, at the same time, setting the conditions to permit the inculcation of a more vibrant and more unified CF culture, will be central to a successful CF transformation. Third, it will also be imperative for General Hillier to retain the focus on the strategic imperative he has established as part of this new CF vision – improving operational effectiveness – so that it becomes institutionalized as the organizing concept for the CF and for decision-making. Finally, to overcome the “bureaucratic fog” that inherently exists at National Defence,65 which creates inherent resistance to change, it will be essential for this CF transformation to maintain high momentum. This will likely be best achieved through the establishment of short-term focused goals that perpetuate rapid incremental changes, and by the reinforcement of new roles, behaviours and processes consistent with the main themes espoused for this transformation effort.

DND photo AR2005-A01-253a by Captain François Giroux

General Hillier (centre) and Minister Graham (right) touring Canadian facilities in Afghanistan.

Throughout Minister Hellyer’s four-year tenure as MND, a great amount of emotion was involved in the imple-mentation of the government’s defence policy – emotion largely centred around tradition, loyalty and identity of the services – and he faced stiff resistance in his attempts to integrate and unify the CF, and to centralize decision- making. Terms such as ‘integration’ and ‘unification’ have become associated with the 1960s, and the appearance of similar terminology in the 2005 Defence Policy is drawing the inevitable comparisons between the two individuals and their initiatives. While “Hellyer and Hillier may share a vision of the Canadian Forces fighting as an integrated whole,” as one military analyst recently observed, the analogy between the two initiatives ends there.66

Three important factors make the 2005 CF transformation drastically different from the 1960s unification of the Canadian Forces. First, the domestic political environment and the context of the two periods are markedly different, and the two implementers, Minister Hellyer and General Hillier, have completely different backgrounds. An ambitious Minister Hellyer took over Defence in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Glassco Commission and several defence procurement fiascos, convinced that he had to impose change at Defence. An operationally-hardened General Hillier assumed command of the CF with the events of 9/11 still fresh in the mind of Canadians, and with a prime minister in office who has expressed his desires, through many statements and the International Policy Statement, to restore Canada’s place in the world community of nations. The CDS urged new thinking about the CF, and proposed new roles for the Canadian military – focused upon establishing Canada as a theatre of operations, and upon stabilizing failed and falling states. Moreover, the CDS assumed command of the CF with public confidence in Canada’s armed forces at its highest level in decades.

Second, while the fundamental roles for Canada’s armed forces in both the 1964 White Paper and the 2005 Defence Policy are similar, Minister Hellyer’s dominant ideas for the structuring of Defence are almost diametrically opposed to those advocated by General Hillier. Minister Hellyer’s integration and unification concept was focused upon centralization of decision-making and administrative efficiency, which eventually drove him to reduce the size of National Defence in order to control rising costs. General Hillier’s initiative, expressed in the CF vision of the 2005 Defence Policy, articulates requirements for improved operational capabilities to meet security demands at home and abroad. The need to increase CF operational effectiveness has been significantly influenced by General Hillier’s many operational command experiences of the past 10 years. In addition, the Liberal government has made a solid financial commitment to Canadian defence, unparalleled in the past two decades. Therefore, the CF is expected to grow in the coming years.

Third, Minister Hellyer’s approach for changing the defence structure was initially focused at the top of the defence establishment through the creation of the office of the CDS, then working progressively down the chain of authority during his four-year tenure, culminating with the elimination of the three services in 1968, and the introduction of a new and common green uniform. General Hillier’s fundamental restructuring is initially targeted at the operational level of the CF, which will see the creation of three new operationally focused commands during the spring of 2006. Other structural changes to the CF can be expected to help further operational effectiveness.

Equating the 2005 CF transformation with the 1960s unification of the CF is erroneous. It is evident that this transformation is not the last chapter of the unification story. Rather, it is another important waypoint in the continued evolution of Canada’s armed forces.

![]()

Brigadier-General Daniel Gosselin, OMM, CD, a PhD candidate in military history at Queen’s University, is currently the Chief of Staff, Canadian Forces Transformation Team at National Defence Headquarters. Doctor Craig Stone is the Deputy Director of Academics at the Canadian Forces College in Toronto, and an Adjunct Professor in the Politics and Economics Department at the Royal Military College of Canada.

Notes

Authors thanks to Dr. Allan English, Queen’s University.

- Some military analysts have already alluded to these similarities. See Richard Gimblett, testimony to the Senate Standing Committee on National Defence and Security, 21 February 2005; and also, Nick Boisvert, “Bold Talk – But Can We Bank On It?” Council for Canadian Security in the 21st Century, 1 March 2005.

- Paul Martin, “Forward from the Prime Minister,” Canada’s International Policy Statement: A Role of Pride and Influence in the World (Ottawa: Department of Foreign Affairs, 2005), p. 2; and Paul Hellyer, “Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence No. 14, Standing Committee on National Defence,” (Tuesday, 7 February 1967, Respecting Bill C-243, An Act to amend the National Defence Act and Other Acts in consequence thereof), (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1967), p. 440.

- Government of Canada, A Role of Pride and Influence in the World: Defence, April 2005, pp. 11-13.

- The term ‘integration’ has different meaning in Canadian defence, depending on the period being discussed. Before 1972, ‘integration’ refers to the amalgamation of the headquarters, commands, and support establishments of the three services, while preserving the services themselves as separate institution, while ‘unification’ means the establishment of a single military service in place of the army, navy and air force. David P. Burke, “Hellyer and Landymore: The Unification of the Canadian Armed Forces and an Admiral’s Revolt,” American Review of Canadian Studies, VIII (Autumn 1978), p. 26, Note 1.

- For the purpose of this article, the 1960s integration and unification initiative launched by Minister Hellyer will be referred to as ‘CF unification’, while the implementation of the 2005 defence policy by General Hillier will be referred to as the ‘CF transformation’.

- Douglas L. Bland and Sean M. Maloney, Campaigns for International Security (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), pp. 51-53.

- Douglas Bland, The Administration of Defence Policy in Canada (Kingston: Ronald P. Frye & Company, 1987), p. 35.

- Douglas Bland, Chiefs of Defence: Government and the Unified Command of the Canadian Armed Forces (Toronto: The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies, 1995), p. 2

- Peter T. Haydon, The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis: Canadian Involvement Reconsidered (Toronto: The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies, 1993), p. 1.

- The Liberal Party under Pearson ran in 1963 on a platform promising that, if elected, they would begin their term with ‘60 Days of Decisions’ on questions such as introducing a new Canadian flag, reforming health care and a public pension plan.

- Paul T. Hellyer, “Canadian Defence Policy,” Air University Review Vol. 19, No. 1 (November-December 1967), p. 3.

- Canada, Department of Finance, Fiscal Reference Tables October 2004 Tables 1 and 7 (Ottawa: Public Works Canada, 2004), pp. 9, 15.

- This commission was referred to as the Glassco Commission – named for its chairman, T.J. Glassco. One report of the Commission focused on Defence, due to its large size, the composition of Department, and the range and cost of its activities. The Commission recommended that the three armed services should be integrated under a single authority.

- Paul Hellyer, Damn The Torpedoes: My Fight to Unify the Canadian Forces (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1990), p. 36.

- Bland, Administration of Defence, p. 31.

- See Hellyer, Damn The Torpedoes, p. 36; and Douglas Bland, Canada’s National Defence: Volume 1 (Kingston: Queen’s University, School of Policy Studies, 1997), pp. 59-61.

- Bland, Canada’s National Defence: Volume 1, p. 59.

- In 1947, these were to “defend Canada against aggression; to assist the Civil Power in maintaining law and order within the country; and, to carry out any undertakings which by our own voluntary act we may assume in co-operation with friendly nations or under any effective plan of collective action under the United Nations.” Bland, “Introduction to Canada’s Defence 1947,” in Canada’s National Defence: Volume 1, p. 1.

- The 1964 White Paper indicated that the priorities for the Canadian Forces were: forces for the direct protection of Canada, which can be deployed as required; forces-in-being as part of the deterrent in the European theatre; Maritime forces-in-being as a contribution to the deterrent; forces-in-being for UN peace-keeping operations; and Reserve forces and mobilization potential. 1964 White Paper, p. 24.

- 1964 White Paper, p. 30.

- Hellyer, in Douglas Bland, Canada’s National Defence: Volume 2: Defence Organization (Kingston: School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University, 1998), p. 113.

- Air Marshal FR Sharp, “Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, No 14, Standing Committee on National Defence,” p. 461.

- Both quotes from Hellyer, in Bland, Canada’s National Defence: Volume 2, pp. 109, 132.

- White Paper on Defence, in Bland, Canada’s National Defence: Volume 2, p. 92.

- David Bercuson, Significant Incident: Canada’s Army, The Airborne, and the Murder in Somalia (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1996), p.72.

- Hellyer, “Canadian Defence Policy,” p. 6.

- The seven stated aims of unification were: reduce overhead costs to provide more funds for the acquisition of operational equipment; ensure that the resources devoted to the various operational functions in the three services are compatible; establish a posture to take advantage of latest advances in science and technology; modernize management processes as recommended by the Glassco Commission report; increase the flexibility of the forces; provide challenging careers for personnel; and, increase operational effectiveness. Air Marshal Sharp, presentation to the Standing Committee on National Defence, “Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence No. 14,” pp. 442-444.

- Bercuson, p. 72.

- Quite telling of the importance that Hellyer attached to this specific aim of unification, these comments form part of the concluding sentence to his 1967 article defending unification. Hellyer, “Canadian Defence Policy,” p. 7

- Desmond Morton, A Military History of Canada: From Champlain to Kosovo, Fourth Edition (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999), pp. 249-250.

- General Ray Henault, Annual Report 2003-2004, Introduction. The 2003 and 2004 CDS Annual Reports to Parliament, issued under the leadership of General Henault, spoke strongly of transformation. The titles of the report were respectively A Time for Transformation and Making Choices.

- Canadian Defence Policy (Ottawa: Department of National Defence, April 1992).

- 2005 Defence Policy, p. 2.

- General Rick Hillier, “Canadian Forces transformation: from vision to mission,” The Hill Times, 26 September 2005, p. 24, and 2005 Defence Policy, p. 11.

- Douglas Bland, “Change of Command,” The Ottawa Citizen, p. A15.

- 2005 Defence Policy, p. 1.

- 2005 Defence Policy, p. 1. That said, for DND, many “efficiency” themes will be captured through the implementation of the Treasury Board-initiated Public Service Modernization Act that will affect many areas of public sector management, and may have important repercussions on the way the Department of National Defence conducts its business.

- For John P. Kotter, best-selling author of two change management books, increasing urgency for change is the first step for successful large-scale change. John P. Kotter, The Heart of Change (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002), pp. 15-36.

- See, for instance, an article, based on an interview with General Hillier, which states that he arrived at Defence “with an aggressive plan to transform the military and a mere three years to accomplish it.” Tom Feiler, “Mission Impossible,” Saturday Night Magazine, 29 October 2005, p. 29.

- Vernon Kronenberg, All Together Now: The Organization of the Department of National Defence in Canada 1964-1972 (Toronto: The Canadian Institute of International Affairs, 1973), pp. 30-32.

- Ibid., p. 15.

- Ibid.

- Bland, Administration of Defence, p. 52.

- Burke, p. 17.

- Maple Leaf magazine, Vol. 8, No. 37, 26 October 2005, p. 6.

- Some of the major equipment being proposed includes new medium-lift helicopters to transport army troops, ships to support littoral operations, and weapon systems for surface ships.

- This is a move that has been recommended for several years by a number of defence analysts, including Bland. See Bland, Chiefs of Defence, pp. 290-291.

- The CDS established six principles to guide commanders and staff as they execute CF transformation. The CDS principle on “Mission Command” states that “the CF will continue to develop and exemplify mission command leadership – the leadership philosophy of the CF. In essence, mission command articulates the dynamic and decentralized execution of operations guided throughout by a clear articulation and understanding of the overriding commander’s intent. This leadership concept demands the aggressive use of initiative at every level, a high degree of comfort in ambiguity and a tolerance for honest failure.” CF Maple Leaf Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 36, 19 October 2005, p. 7.

- Milner, p. 243.

- Bland, Administration of Defence, p. 52.

- Kronenberg, p. 9 and pp. 15-16.

- In February 2005, the VCDS directed the standing up of four CDS Action Teams, each led by a general/flag officer to investigate the process of initiating the implementation of the CF vision. The mandate of the teams was to examine and analyze specific lines of operations that directly support near-term CF transformation. In addition, the Director General Strategic Planning is developing a comprehensive campaign plan to guide long-term transformation efforts and initiatives.

- General Hillier’s remarks to the press on 15 July 2005. DND, Assistant Deputy Minister of Public Affairs, media transcript 05071501.

- The Deputy Minister announced in October 2005 the creation of a “Defence Institutional Alignment” team, with the mandate to ensure that as the CF transformation evolves, the effects on departmental organizations are appropriately assessed, managed and communicated. Maple Leaf magazine, 26 October 2005, p. 6.

- Both quotes from William P. Belgard and Steven R. Rayner, Shaping the Future: A Dynamic Process for Creating and Achieving Your Company’s Strategic Vision (New York: American Management Association, 2004), p. 4. For a more complete discussion, see also pp. 109-132.

- The CDS specifically raised this point during his 22 September address entitled “The Role of Canada’s Military in the New World Order” for the 2005 Judy Bell Lecture at Carleton University. DND, Assistant Deputy Minister of Public Affairs, media transcript 05092208.

- Term employed by General Hillier in his remarks to the press on 15 July 2005.

- Bland, Canada’s National Defence Volume 1, p. 62. See also, Lewis Mackenzie, “Hillier’s Right, So Back Off,” The Globe and Mail, 1 August 2005,

- R.L. Raymont, The Formulation of Canadian Defence Policy 1968-1973 (Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 1983), pp. 70-77.

- Bercuson, pp. 73-74.

- See Bland, Chief of Defence, 124; Bercuson, p. 74; and Jack Granatstein, Who Killed the Canadian Military? (Toronto: HarperCollins Publishing Ltd., 2004), pp. 69-94. Civilianization is not to be confused with the civil control of the military. Civilianization means civilian public servants taking decisions that are within the realm of the military professional officer.

- Six studies were conducted in the period 1979-1985. Three of those unification studies were completed by Colonel (ret’d) R.L. Raymont, an executive staff officer to three Chiefs of the Defence Staff in the 1950s and 1960s: The Formulation of Canadian Defence Policy from 1945-1964 (Ottawa: DND, 1981), Report on Integration and Unification 1964-1968 (1982), and The Formulation of Canadian Defence Policy 1968-1973: Developments of the Proclamation of Bill C-243 and Implementing Unification (1983). Two government-initiated studies: Task Force on Review of Unification of the Canadian Armed Forces, Final Report (DND, 15 March 1980), and Review Group on the Report of the Task Force on Unification of the Canadian Forces (DND, 31 August 1980); and D.G. Loomis et al, The Impact of Integration, Unification and Restructuring on the Functions and Structure of National Defence Headquarter, NDHQ Study S1/85 (DND, 31 July 1985).

- Raymont, Formulation of Canadian Defence Policy 1968, p. 76.

- For a more complete discussion on the “strong-service idea,” and the CF, see Daniel Gosselin, “Unification and the Strong-Service Idea: A 50-Year Tug of War of Concepts at Crossroads,” in Operational Art: Canadian Perspectives – Context and Concepts, Allan English et al. (eds.) Kingston: Canadian Defence Academy, 2005).

- Belgard and Rayner, pp. 110-115.

- Boisvert, “Bold Talk – But Can We Bank On It?”