This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

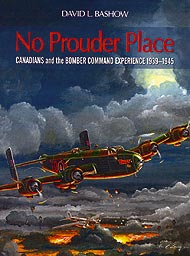

No Prouder Place – Canadians And The Bomber Command Experience 1939-1945

by David L. Bashow

St. Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing, 2005

544 pages, $60.00

Reviewed by Jim Barrett

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Because of the Editor-in-Chief’s obvious association with this book, a member of the CMJ Editorial Review Board edited this review.

Paul R. Hussey, Major General, Chairman,

CMJ Oversight Committee

The Allied bombing of Nazi Germany was a long and brutal campaign, although the early rounds gave little support to Sir Arthur Harris’s belief that heavy bombers could dramatically shorten, or even win the Second World War. Early cross-Channel bombing exchanges between the Luftwaffe and the RAF proved that daylight bombing was far too costly, and night bombing was far too imprecise. Even so, after Dunkirk, the bomber was one of the few long-range offensive weapons available to the British, and it was inevitable that, driven by desperation, the focus would soon shift to area bombing. There appeared to be real hope here. Trenchard, Mitchell and Douhet all had preached that damage to civilian morale would outweigh by far the physical damage caused by bombing. The apparent lessons of Ethiopia and Rotterdam were still fresh – all lending credence to the belief that ‘the bomber would always get through’, and that wars could be won by air power alone. Thus it was that the aircrews and their aircraft became the instruments of terror and death delivered, not only upon the engines and factories of war, but also deliberately upon the civilian populace. The ethics and morality of bombing civilians are different today, and the decisions taken during the Second World War are still hotly debated. But 1940 witnessed the effective beginning of this long and bloody military campaign.

The Allied bombing of Nazi Germany was a long and brutal campaign, although the early rounds gave little support to Sir Arthur Harris’s belief that heavy bombers could dramatically shorten, or even win the Second World War. Early cross-Channel bombing exchanges between the Luftwaffe and the RAF proved that daylight bombing was far too costly, and night bombing was far too imprecise. Even so, after Dunkirk, the bomber was one of the few long-range offensive weapons available to the British, and it was inevitable that, driven by desperation, the focus would soon shift to area bombing. There appeared to be real hope here. Trenchard, Mitchell and Douhet all had preached that damage to civilian morale would outweigh by far the physical damage caused by bombing. The apparent lessons of Ethiopia and Rotterdam were still fresh – all lending credence to the belief that ‘the bomber would always get through’, and that wars could be won by air power alone. Thus it was that the aircrews and their aircraft became the instruments of terror and death delivered, not only upon the engines and factories of war, but also deliberately upon the civilian populace. The ethics and morality of bombing civilians are different today, and the decisions taken during the Second World War are still hotly debated. But 1940 witnessed the effective beginning of this long and bloody military campaign.

While RAF Bomber Command struggled to learn its craft, to develop its aircraft and techniques, the Luftwaffe built a formidable array of ground defences and a capable night fighter force that dealt a fiery death to many aircraft and to the men inside them. For the airman, it was a fearful war of grim statistics, which gave a good chance of surviving the next operation, but a less than 50-50 chance of surviving the required 30 operations that constituted a tour of combat duty.1

After Pearl Harbor, the British were no longer alone. The Combined Bomber Offensive saw the Americans attacking by day and the British by night. New weapons |and new science, together with a steady stream of fresh aircrew, turned the tide and gave new hope to the belief that by this means, German morale could indeed be crushed, and the war could be brought to an early end. For Harris and other proponents of this view, Operation Overlord was an unwise diversion of resources and focus that would unnecessarily prolong the war and increase its cost. In the end, the contribution of the air bombing campaign is still being debated.

Lieutenant-Colonel (ret’d) David L. Bashow, in his fine new book, No Prouder Place – Canadians and the Bomber Command Experience 1939-1945, brings all this to a human level and presents it through Canadian eyes. As evidenced by the first paragraphs of this review, the history of the Allied bombing campaign can be – and often has been – written with no reference to Canada and Canada’s role. There were 40,000 Canadians who served with Bomber Command: as members of the RAF, as members of the RCAF serving in the RAF, as members of RCAF squadrons within RAF bombing groups, and, from January 1943, as members of 6 Group, RCAF. One-in-four became a fatal casualty. There are other books, wonderful personal memoirs like Murray Peden’s A Thousand Shall Fall, peopled by the ghosts of lost comrades, and there is Dunsmore and Carter’s History of 6 Group, but Colonel Bashow combines history and humanity to tell the whole story of the Canadians in the bombing campaign.

No Prouder Place is a story written from the viewpoint of Canadian crews and the aircraft they flew. Bashow pulls off the neat trick of bringing the reader into the minds and thought processes of the people who fought that campaign, and knits the larger picture as it was seen and argued by those who faced the challenges for real. As a result, the moral and ethical issues are not belaboured, but are presented as the clear and natural thinking of men fighting for the survival of a way of life. If there is a lesson to be learned here, it is that we too, placed in that context, would have thought as they did.

This is a large book – 544 pages of text and black- and-white photos, plus a 32-page colour supplement – that takes an interesting approach. The story is told chronologically, from the war’s opening days, through ‘the long dark night’ of 1942 to mid-1943, where the author takes a pause. In effect, he steps back, and asks the questions: What was it like for the crews, for the ground crews, for the civilians? How did men find the courage to risk a fiery death one more time, and again one more time? Bashow deals thoroughly and sympathetically with these questions, concluding that the bombing campaign produced the ultimate in small team cohesion: crew loyalty and fighting spirit were the greatest contributing factors. These reflections concluded, we return to the relentless pace of the war, through the Berlin campaign to the high water mark of operational losses, Nuremburg in March 1944, then on to the closing days of the war. The arguments between Portal and Harris, Harris’s near-insubordination over targeting diversions, and his resistance to supporting Overlord, the missives from Churchill, the British reaction to Canadianization – all these are present in good measure. But from beginning to end, Bashow’s focus is the human dimension. His stories – many of them new – are from pilots, navigators, bomb-aimers and wireless air gunners, and also from ground crew. He shows great affection for the airplanes too, and gives the Halifax – warts and all – its due recognition as the workhorse of the campaign. The generous collection of photos, the vivid and terrifying artwork of Ron Lowry and Pat McNorgan, as well as various other paintings and drawings, make this a complete work.

Finally, it is necessary to say something about his Appendix: The Balance Sheet. This is not a balance sheet in the conventional sense, but rather a series of arguments that seeks to restore the balance of modern opinion about the value of the campaign. Critics and revisionists continue to argue that the bombing campaign was a moral and strategic error that wreaked devastation on the cities of Europe – and was criminally wasteful in the lives of civilians and aircrew – all for little strategic return. At its best, they say, the bombing campaign was a waste of resources that could better have been used elsewhere. At its worst, it was butchery.

Area bombing of enemy cities is now illegal, a fact that has undoubtedly influenced the modern debate. It is nonetheless worthwhile to consider the value of the campaign in the context of that time, and to see it against the war morality of that time. While admitting that there was less damage to strategic targets than had been intended, Colonel Bashow makes a convincing case that the investment in lives and materiel lost was modest relative to the benefits achieved. The reader will have to make his or her own determination, but few would dispute that the men who fought that campaign were both brave and moral. Their losses were appalling, and those who survived still bear the scars. Long after the rebuilt cities have replaced the ash and the rubble, veterans of this campaign are torn between pride and guilt, between a belief in their contribution and doubts about the success of their efforts. Their war was never recognized officially as a campaign, and no medal was ever struck to honour the participants. No Prouder Place is a fine tribute to their contribution and to their sacrifice.

![]()

Doctor A.J. Barrett is the Director of Learning Management at the Canadian Defence Academy and Vice-Principal of the Royal Military College of Canada. He served as an air navigator with 405 Squadron from 1965 to 1967.

Notes

- Bomber Command hoped to keep the loss rate to 3 percent per mission or operation. The statistics work like this. If your probability of ‘loss’ is 3 percent per mission, then you have a 97 percent chance of surviving that mission. This doesn’t sound too bad, but if you are to survive a tour of 30 missions, you must survive the first one, and the second one, and the third one, and so on... The probability of surviving all 30 is (0.97)30 x 100 = 40 percent. Your chance of not surviving the 30 missions is therefore a frightening 60 percent. Another interesting statistic is the expected lifetime of a crew or aircraft, measured in individual missions or operations. If the probability of loss is ‘p’ percent, then, mathematically, on average, a crew could expect to survive (100 – p)/p operations. It is thus understandable that 6 Group would worry about an average loss rate per mission of 5 percent, since this meant that crews would last only 19 missions, on average, and the individual survival probability then drops to 21 percent under those circumstances.