This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Maritime Issues

DND photo

HMCS Kingston Maritime coastal defence vessel.

Enhancing The Naval Mandate For Law Enforcement: Hot Pursuit Or Hot Potato?

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Days after the 1995 apprehension of the fishing vessel Estai on the Grand Banks, the Toronto Sun carried a provocative front-page periscope photograph of a Spanish stern trawler at close range. This so-called ‘Turbot Crisis’ brought fisheries and sovereignty issues into focus for Canadians. Moreover, the reporting of this unusual employment of a submarine was, for many, the first indication that their navy played an active role in the enforcement of domestic and international law in Canada’s maritime zones.

While Canada’s navy has always been active in the nation’s maritime affairs, there is a case to be made for expanding the naval role with respect to domestic maritime enforcement in support of safeguarding national security and the exercise of Canadian sovereignty. The intent of this article is to suggest why a more comprehensive role is both practical and necessary. The Canadian Navy maintains a significant presence in Canada’s maritime zones, and it should have all the legal tools required to enforce Canadian law in those regions. This is not to suggest that the navy would shift its primary emphasis from preparing for combat at sea to coast guard duties. Rather, it is an appeal for powers that would enable the navy to act upon violations detected while carrying out its fundamental military role. Other government departments have become increasingly reliant on the navy during a decade of government-wide retrenchment. The issues that shape attitudes towards the employment of armed forces for law enforcement tasks also need to be identified and challenged. Finally, a simple model for executing this new role will be proposed. But first, it is necessary to examine what the navy’s enforcement role is at present.

Naval Contribution to Maritime Enforcement

For the past several years, all federal departments and agencies have suffered the consequences of reduced budgets. Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) have experienced significant pressures with respect to operating aging fleets in the face of increased demand for post-9/11 patrol activities. Indeed, Senator Colin Kenny complained in 2004 that the CCG, the navy, and by extension, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), were not defending Canada’s coasts in “any meaningful way”.1 While this may be an overstatement, in reality no single government department or agency on its own can assure the safety, security or sovereignty of Canada. Thus, any additional contribution the navy can make – either by itself or in partnership with other government departments – could enhance significantly Canada’s ability to exercise national sovereignty.

At present, the navy’s contribution to domestic maritime enforcement is maintaining a comprehensive surveillance and domain awareness capability, providing routine support to departments with enforcement mandates, and being prepared to apply coercive force in emergent crises. Over the past decade, on the Atlantic coast, Canadian naval vessels spent between 150 and 250 days at sea per year, many of them on overseas deployments, but the majority of them within the nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). While many of these sea-days were devoted to training and exercises, they provided many ‘eyes on the water’, and constituted a distinct federal presence in Canada’s maritime approaches.2 In recent years, the navy has spent fewer and fewer days at sea, due to reductions in fleet size and annual budgetary constraints.

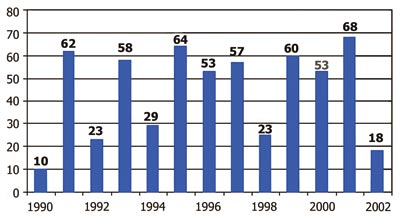

In addition to its at-sea presence, the navy is already an active participant in fisheries enforcement through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) negotiated between the Department of National Defence (DND) and DFO. This MOU defines the terms and procedures for the provision of support by the navy and the air force, and it sets the number of sea-days (Figure 1) and flying-hours allocated to surveillance and fisheries enforcement. Naval vessels and military maritime patrol aircraft, with DFO officers embarked, conduct fishery patrols in the inshore and offshore maritime zones. Essentially, they provide the means to transport fisheries officers into areas of fishing activity so that the appropriate authorities can monitor, inspect, and, if necessary, arrest anyone violating domestic and/or international law.

Figure 1 – Naval Fisheries Patrol Sea Days – Atlantic. (Maritime Forces Atlantic Sea Operations staff, 2004)

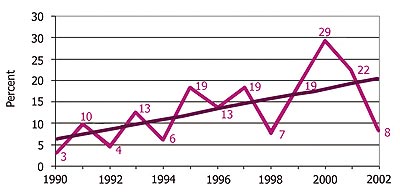

Figure 2 – Boardings by Fisheries Officers Embarked aboard Naval Ships – Atlantic. (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2002)

Figure 3 – Navy’s Percentage of Total DFO Boardings for Newfoundland Region. (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2002)

Over the past several years, DFO has, in fact, begun to rely increasingly on the navy for support, particularly since DFO reduced its offshore enforcement fleet. While the number of boardings carried out by DFO officers embarked aboard naval vessels remains relatively constant (Figure 2), the overall percentage of boardings instigated by fisheries officers embarked in naval vessels is increasing (Figure 3).

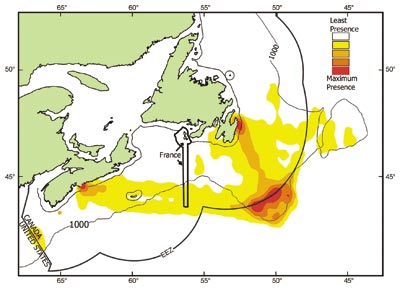

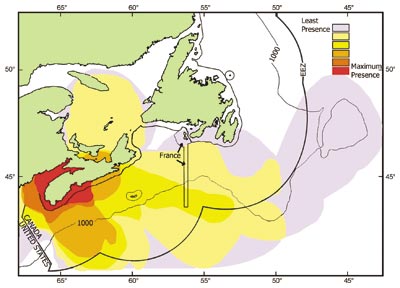

Historically, the navy has focused its fisheries patrols upon the Grand Banks, resulting in the emergence of distinct patterns of naval presence. Figure 4 shows a concentration of patrol effort on the Tail of the Grand Banks, with increased presence on the routes to and from Halifax and St. John’s.3 The focus on the Tail was due in large measure to the plethora of foreign vessels attracted to this particularly abundant fishing ground, and then later in the 1990s, to the requirement to enforce the moratorium imposed on the Tail as a result of plummeting ground fish stocks. Figure 5 captures the shift in concentration away from the Tail where, by 1999, only a small total allowable catch had been allocated. The new direction was towards the Flemish Cap, where other species such as shrimp were, and still are, commercially viable. Figure 6 depicts the coverage and, by extension, the presence of military maritime patrol aircraft during a routine 30-day period.

As demonstrated by the preceding figures, the Canadian Navy is fully engaged in safeguarding both national security and the exercise of Canadian sovereignty. In a period when patrol activities by other government departments has been waning, the navy continues to maintain a not insignificant ‘on-the-water’ presence in Canada’s maritime zones. The navy’s tendency to revisit areas of high activity and traffic density – coupled with its sophisticated modern sensor capability – predisposes its vessels to detect breaches of domestic and international law. However, at present, unless a peace officer from another government department is embarked, there is little recourse open to a naval vessel other than to report the situation to the appropriate law enforcement authority, and to wait for action to be taken by others. Why then has Canada been so reticent to take the next step, as have many other nations, to employ the navy for enforcement of federal statutes in all Canadian maritime zones in a more primary manner than relegating it to its present supporting role?

Figure 4 – Enforcement Presence by Naval Ships on Fisheries Patrol: 1980 – 1996. (National Library and Archives data from 59 ship’s logs)

Figure 5 – Enforcement Presence by Naval Ships on Fisheries Patrol: 1999 – 2000. (Data from 13 naval fisheries patrols)

Figure 6 – Presence of CP-140 AuroraMaritime Patrol Aircraft: 15 Jan – 15 Feb 2004. (Data from 18 flights)

Reticence to Use Armed Forces for Domestic Enforcement

There is no simple answer to this question. However, an explanation can be found in a number of separate but related issues. Public perceptions of the army, and a general unease with the use of the army for law enforcement on land, have influenced how constabulary naval roles are viewed. At heart is the public’s apparent inability to distinguish between the army and the navy in terms of domestic operations. In addition, some also question whether law enforcement is truly a legitimate use of the Canadian Forces in the first instance. Lastly, there are those who argue that constabulary duties are non-traditional, that they detract from the status of a navy, and that they erode its war fighting capability. On further examination, it becomes evident that these concerns do not present such an insurmountable obstacle as may first have been thought.

The Army and Law Enforcement

As instruments of national power, most Western armed forces have been conceived and maintained to execute state policy abroad – although they can also be employed domestically in certain situations where their unique military attributes can be used very effectively. In practice, democratic governments constrain the internal use of their militaries, usually to avoid potential political fallout, and also, to maintain the legitimacy of their democratic governance. Canada is no exception, and this tradition has its roots in British legal heritage, which was imported to British North America before Confederation.

It is argued that the perceived unwillingness to employ the Canadian Army in law enforcement roles during modern times comes from long-standing prejudices resulting from misuse of the army in foregone times. The British Bill of Rights of 1688 is the point of departure for an analysis of civil-military relations in the British Isles, and, by extension, the Dominion of Canada. This Act rendered the army subordinate to Parliament, and restricted its use by the Crown.4 Interestingly, the Bill of Rights of 1688 makes no reference to the Royal Navy, a powerful arm of the state during that particular period of empire building. Clearly, it was not viewed as a threat to the domestic political structure of the era. After the Bill of Rights, there followed a series of acts that provided statutory authority and funding for armed forces to operate on land.

For well over two centuries, the army remained an important tool in the execution of domestic policy, largely because it was the only organized body of men that the Crown could call upon for its coercive ends. Consequently, well into the 19th Century, soldiers were employed frequently to maintain public order, notwithstanding the potential risk to civil liberties. Over time, public figures began to question the means employed to maintain law and order, as well as the appropriateness of the use of the army for this purpose. This evaluation coincided roughly with the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829, and the creation of Britain’s fledgling police forces.

Attitudes toward the use of the army in the domestic context ultimately migrated to Canada. Here, the army was used prior to the Second World War to quell disturbances, to suppress election disorder, and to put down uprisings, such as the Riel Rebellion of 1885. Some argue that the negative memory of these actions remains embedded with today’s population, resulting in resentment towards using the Canadian Army to quell civil disorder. However, it is difficult to gauge accurately public sentiment about the use of the army for law enforcement purposes. There have been only four instances of the use of Canadian military forces in their most intrusive form since 1945.5 In the case of both the 1970 FLQ and the1990 Oka crises, the armed forces were praised for the calm and disciplined manner in which they both contained the crisis and prevented its escalation.6 If there is truly lingering resentment over use of the Canadian Forces for law enforcement tasks, it is difficult to explain why visible military assistance is requested for major politically-charged events, such as the G8 Ministers’ conferences in Kananaskis and Halifax, or the Summit of the Americas in Quebec City.

Legitimacy of the Canadian Forces for Law Enforcement

Contrary to what many might think, law enforcement is, indeed, a legitimate function of the Canadian Forces. Parliament has indicated clearly both its acceptance of and its expectation that the armed forces have a role in law enforcement in certain circumstances. This statutory basis can be found in the National Defence Act (NDA). This Act codifies the principles for control of the armed forces, and provides the legal framework for the provision of military support to provinces or other government departments for maintaining public order.

Parliament has two major expectations in relation to the armed forces and law enforcement. First, the Canadian Forces must be capable of a broad spectrum of services provision in both crisis and non-crisis scenarios. Through the NDA, Parliament empowers the Minister of National Defence or the Governor-in-Council to authorize the armed forces to “perform any duty involving public service”, including the “provision of assistance in respect of any law enforcement matter”. This commonly takes the form of humanitarian assistance – including ground search and rescue, aid to civil disasters, such as floods and fires, environmental emergencies and other humanitarian situations, such as missing persons and mercy flights. The “provision of assistance in respect of any law enforcement matter” clause also encompasses what is known as assistance to law enforcement agencies (ALEA). Within this category, support from the armed forces runs the gamut from the benign, such as provision of ranges or training areas for police use, to situations in which a disturbance of the peace is occurring or is about to occur, and when armed forces personnel or equipment may be required for support. The NDA also sets the conditions for armed forces support to federal penitentiaries for assisting in the suppression of prison disturbances, and it provides authority for the earlier mentioned MOUs with DFO, the RCMP, and with Environment Canada (EC). These MOUs provide the legal basis for the navy to assist the other federal departments to enforce narcotics, fisheries and environmental laws through use of naval assets for surveillance, information sharing and interdiction support.

Second, Parliament expects the Canadian Forces to be capable of taking responsibility for restoring public order when necessary – that is, for coming to the aid of the civil power. Pursuant to the National Defence Act, military ‘service’ can be furnished “in any case in which a riot or disturbance of the peace, beyond the powers of civil authorities to suppress, prevent or deal with and requiring that service”. The Chief of the Defence Staff is accorded the discretion to determine the scope and nature of military ‘service’ in these situations. Under aid of the civil power, armed forces members possess the powers and duties of ‘constables’, but they remain under military command and control.

Aid of the civil power is an arguably controversial ‘service’, since it conjures up images of soldiers with rifles patrolling Canadian streets, and, in the view of some citizens, it embodies the idea of a police state with the threat of concomitant suspension of civil liberties. Historian Sean Maloney asserts that employing military forces domestically is a “politically provocative act, one that carries much weight regardless of the situation”.7 Others argue that the use of military forces for law enforcement purposes obfuscates military and civilian roles, undermines civilian control of the armed forces, and is not an appropriate use of resources.8 This criticism notwithstanding, the police state has never been an acceptable concept in Canada, and the infrequent requisitions for aid to the civil power are always undertaken as a means of last resort. Moreover, as stated earlier, recent examples of armed forces employment in aid to the civil power met with overall approval. More importantly, however, Parliament has demonstrated, through various legal instruments, that it both accepts and expects Canada’s military to play a role in law enforcement, but that role will be subject to tight political control.

Do constitutional issues prevent the navy, as opposed to the army, from enforcing Canadian law? A review of the Constitution Act indicates otherwise. The Act states that “...the exclusive Legislative Authority of the Parliament of Canada extends to... Militia, Military and Naval Service, and Defence... Beacons, Buoys, Lighthouses... Navigation and Shipping... Sea Coast and Inland Ferries”. Such subjects are clearly related to maritime activities on or beyond the coasts, and the Act codifies federal responsibility for each. The Act also prescribes the exclusive powers of the provinces, powers that focus on activities and issues affecting provincial territory, namely, terra firma.9 Thus, the Constitution Act clearly implies that Canada’s ocean zones are federal jurisdictions. As such, appropriate organs of the federal government may enforce Canadian law within these jurisdictions, provided they have the legal mandate. In order for the navy to enforce rather than just assist in enforcement, relatively minor amendments to various maritime-related enabling statutes are required.

Lack of Distinction between Army and Navy in ‘Domestic Operations’

Notwithstanding Kananaskis and other fora, in which the Canadian Forces deployed in high profile support of enforcement agencies, public perception commonly views ‘traditional’ military law enforcement operations as those in which the army is the ‘agency of last resort’. For many, no distinction exists between the navy dealing with narcotics smuggling, pollution, and fisheries violations at sea, and the army conducting aid to civil power operations on land. The latter are very visible, affect large numbers of citizens, and can be intrusive upon normal life, whereas naval enforcement operations are largely invisible to the majority of Canadians. Due to this lack of distinction, negative biases derived from perceptions of the army’s operations are unconsciously applied to those of the navy.

Enforcement as Non-Traditional Employment

When the question of naval law enforcement is raised, policymakers, lawyers, and senior bureaucrats are naturally reticent to concede any case for enhancing the Canadian Navy’s constabulary role, because such activities are ‘non-traditional’. It can be argued that MOU-based counter-narcotics, fisheries, customs, and immigration law enforcement operations carried out by the navy are not considered in the same category as the ‘force of last resort’ missions. Rather, these types of operations are deemed more to fall into the realm of support to law enforcement agencies. That these operations are seen to be a ‘non-traditional’ role for the navy is both unfortunate and misinformed. Indeed, the need for fisheries protection from American interests in Canadian waters at the turn of the century was a major factor with respect to the creation of an indigenous navy.

Among naval analysts, the employment of navies for constabulary tasks is not a universally popular concept. Vice-Admiral (ret’d) Gary Garnett stresses the importance of maintaining a distinction between the enforcement roles of the Canadian military and civilian authorities. He notes, as have many other analysts, that, in Canada, law enforcement has been traditionally a civilian function. With respect to naval law enforcement, there are disadvantages to employing naval vessels in these roles. The most apparent is that navies are designed generally for war-fighting, not necessarily constabulary tasks. In fact, during the ‘Cod Wars’ with Iceland in the 1970s, British frigates proved to be too ‘overly-sophisticated’ for the task.10 Garnett’s principal concern is to avoid the watering down of combat skills, and his point, in my view, has some validity. However, the intent would not be to convert the Canadian Navy into a fleet of coast guard cutters. Rather, naval ships would continue to train for their primary combat roles, and small teams would receive additional specialized training to become proficient at their secondary constabulary duties.

Maritime Warfare expert Commander (ret’d) Peter Haydon argues that the navy should be the key contributor to sovereignty and security patrols of Canada’s maritime zones, because Defence is the sole department that has the capability to do the patrols properly and efficiently, and the navy is the only organization that understands and can implement the concept of sea control.11 But he also cautions against too much ‘constabularization’, to the point that the nation possesses only a coast guard. In that scenario, he argues that Canada would find itself excluded from multinational naval operations. Both Haydon and Garnett suggest that sending forces perceived to be of a constabulary nature to international operations would signal a weak commitment by Canada to alliance or coalition objectives. Haydon argues that Canada’s overseas commitments would then be limited to token army and light airlift participation, largely because Canada would lose its seat at the table at major international crisis management events. Canada’s use of the navy to further diplomatic ends, to strengthen alliance relationships, and to engage in confidence-building measures would not be possible, and that would marginalize Canada on the world stage.12 This effect runs counter to the government’s stated desire to regain Canada’s stature and influence in the international system.

This potential for marginalization expressed by both Haydon and Garnett would be legitimate, if the Canadian Navy were to be viewed in the future largely as a constabulary force. However, as long as the navy maintains the primacy of combat operations as its raison d’être, and trains to that end, the likelihood of such marginalization is remote.

Garnett also suggests that the presence of a combined civil-military force that executes law enforcement tasks on a routine basis could potentially inflame sensitive international situations, as was the case during the British/Icelandic ‘Cod Wars’.13 However, it can be argued that concern with respect to provocation is really an issue of expectation. The Canadian tradition has been that of civilian law enforcement in the marine environment, and other nations have come to expect that reaction. As political scientist Colin Gray points out: “If Canadian law is accepted as authoritative, and if the law is invoked against a single vessel and not against a state, there should be no provocation.” Likewise, he adds, since so many other countries use their navies for fisheries protection, it can be argued that there is a strong prima facie case for Canada to follow suit.14

Garnett is not alone in his reservations. Other serving and retired flag officers are opposed to their Service taking on a more active domestic maritime enforcement posture. In attempting to understand why this is the case, and one cannot discount simple deep-seated biases. Naval analysts, such as Mark Janis, Richard Hill and Eric Grove, offer various topologies for ranking navies by class. Generally, superpowers sit at ‘the top of the pecking order’, while at the lowest rungs are found the ‘constabulary and token’ navies. Canada ranks its own navy at Level Three, far away from those navies described as being ‘constabulary’.15 The relevance? Simply put, there is a general correlation between ranking of a nation’s navy and a nation’s status in the international system. The majority of navies of developed countries occupy the upper tiers, whereas the navies of developing nations, those of a more constabulary nature, are found in the lower end of the ranking spectrum.16 The Canadian Navy, given its early roots as a fisheries protection force, wished to shed that image and become a ‘real’ navy. Arguably, some senior naval leaders may perceive a certain stigma if their fleets are associated with constabulary rather than combat-capable functions that rank them higher on the international stage. Thus, the attitudes of modern naval officers might well be a legacy of concern with respect to image.

Toronto Sun (Toronto), 6 June 1995. Periscope image taken by author

The provocative, front-page periscope photograph.

Both Garnett and Haydon have cautioned against ‘non-traditional’ law enforcement by Canada’s naval forces. However, John Thomas, former Commissioner of the Canadian Coast Guard, is more blunt:

I do not think that DND should have the role of coastal security... Navy personnel are trained for war and navy systems are developed for war, not to fulfil a policing role on the coast... the navy should be called upon only when the police force cannot do the job... there is a need for a flexible response. The military should be seen, from a policy perspective, as a force of last resort, in the same way as they are for land-based police operations.17

Thomas – and, to a lesser extent, Haydon and Garnett – speaks to a bipolar world of a bygone era, during which Canada’s Navy was structured to counter symmetric threats. It is unlikely that North America will face a conventional military threat, such as had been the case during the Cold War. The maritime security environment changed with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and its continuing evolution was punctuated with the terrorist attacks of 2001. Globally, societies are witnessing an increased emphasis on asymmetric capabilities by organized crime and a variety of trans-state actors. It is reasonable to assume that terrorist groups are prepared to use merchant vessels to transport their personnel and weapons. Any number of scenarios can be imagined here.

In addition to counter-terrorism, the protection of fishing rights, the prevention of illegal activity at sea, and the protection of the environment will continue to require vigilance on the part of the federal government. Canada’s national security policy, Securing an Open Society, calls for effective, integrated multiple-agency threat assessment, protection, and prevention capabilities. However, it is no longer easy to divine what the sovereignty protection role of the Canadian Navy is when, as observed in Canada’s International Policy Statement (IPS), “the boundary between the domestic and international continues to blur”.18 The IPS insists that security and defence policy must change. Thus, it is time to discard old ideas about traditional employment, and to consider what is practical and relevant for the future maritime security environment. Other nations have already done so.

Fisheries protection has long been a traditional role for European naval and coast guard forces. Britain’s naval experience in this role dates back to the 16th Century. At present, the Royal Navy undertakes quarantine enforcement, fishery protection, contraband operations, drug interdiction, oil and gas field patrols, anti-piracy operations, support to counter- insurgency operations and maritime counter-terrorism. Moreover, the Royal Navy maintains a Fishery Protections Squadron, equipped with six offshore patrol vessels and four mine counter-measures vessels. Looking at other parts of Europe, the French Navy, for example, acquired patrol vessels several years ago for policing duties. Farther north, the Norwegian Coast Guard forms part of the Royal Norwegian Navy, whereas Denmark has no coast guard. However, the Danish Navy exercises police authority for enforcement of sovereignty issues. European navies generally furnish law enforcement services directly to national authorities through MOUs. Usually what these navies provide are naval platforms and facilities. In some cases, such as the Danish model, the navy carries out constabulary and traffic-police duties, whereas the appropriate civil authority conducts the criminal investigations. From a European perspective, naval participation in law enforcement is a significant contribution to good governance at sea.19

United States Experience with Posse Comitatus

It is interesting to compare the Canadian position to that of the United States – where the law has, until recently, prohibited the use of the armed forces for domestic enforcement. The Posse Comitatus Act was passed in 1878 to prevent the US Army from carrying out law enforcement tasks in the United States. This was a reaction to the use of military forces in the Confederate states for the maintenance of peace and good order, to the enforcement of policies for post-Civil War reconstruction, and to ensure that rebellious sentiments did not re-ignite. The US Congress became concerned when the army stationed troops at political events and polling stations under the premise of ensuring civil order. The intent of the Posse Comitatus Act was to prevent the Army from becoming ‘the national police force’, and to return the army to its proper role in defence of US territory.20

Interestingly, the Posse Comitatus Act did not apply to the US Navy, only the US Army. It is possible that, as with Britain’s Bill of Rights of 1688, the navy was not viewed as a threat to the US domestic political structure of the era. In 1956, the Posse Comitatus Act was amended to apply to the US Air Force, but, curiously, it made no mention of the US Navy. By 1974, it was interpreted that, although the Act did not specifically apply to the navy, its principles were to be upheld. However, a loophole allowed the navy to be employed for civilian law enforcement purposes, given the express permission of the US Secretary of the Navy, a civilian official. Thus, the paramount principle of civilian control over military forces could be maintained.21

In 1982, at the request of the US Department of Transport, the US Secretary of Defense approved US Navy support to the US Coast Guard for law enforcement purposes. Specifically, the US Navy could conduct surveillance, tow or escort seized vessels, transport prisoners, provide logistic support to Coast Guard units, and embark Coast Guard personnel to conduct boardings of American and stateless vessels. These powers and procedures marked a considerable departure from the outright prohibition of US naval involvement in law enforcement, and they indicate American acceptance of this role for their navy.

Having established the legitimacy of the use of the navy for law enforcement purposes, and having challenged some perceptions about constabulary and non-traditional naval employment, it remains to be discussed what an enhanced mandate for naval law enforcement would really entail.

Proposal for Naval Maritime Enforcement of Canadian Maritime Zones

This article calls for the navy to be empowered with the legal authority to enforce directly selected federal statutes on a routine basis throughout the maritime zones of Canadian jurisdiction. At present, Canadian naval forces are relegated to a support function only, except under special circumstances when coercive force is required, and is requested by the appropriate Minister.

If these legal powers were to be granted, what would this new role entail? The navy’s fundamental mission would remain the “generation and maintenance of combat-capable, multi-purpose maritime forces to meet Canada’s defence objectives”. Nonetheless, if naval vessels detected violations to Canadian law while conducting their defence or sovereignty missions, they would have the requisite legal tools to act upon those discoveries. However, there is no suggestion that the navy would be obliged to cease its principal operations to deal with violations detected. Rather, the naval commanding officer’s decision whether to enforce the law would be shaped by the priority of his naval operations – and by the circumstances of the violation detected. In practice, this precedent already exists. Throughout Canada, police officers have similar discretion to choose when and where to enforce laws, with due consideration to the severity of the offences, the risk to the public, and so on. As well, the navy would not be expected to enforce all federal statutes, only those that apply to specific activities on the seas. These interventions would be limited only to those offences that are directly linked to the protection of Canadian sovereignty, and this constraint should allay concerns referred to earlier about placing police power in the hands of military personnel.

The proposed new role would not envisage the navy conducting investigations of violations detected at sea. Rather, naval personnel would carry out the preliminary work designed to contain the scene of the violation. Again, an analogy of normal police work is useful. Throughout Canada, general duty police officers are normally first at the scene. They then turn over difficult or serious cases to specialist officers or detectives. The general duty officer is trained in basic policing functions – such as understanding how not to contaminate a crime scene, how to maintain care and custody of evidence, and so on – so that qualified detectives can investigate the case in detail. This basic knowledge is necessary to ensure that the Crown’s case is not undermined by procedural errors at the outset of an investigation. In the model proposed, naval personnel would act as the general duty officers, and would turn over the case for investigation by DFO or by EC representatives, or by the RCMP as appropriate. Moreover, the support to enforcement already established by interdepartmental MOUs would not change. Thus, routine patrols with fisheries or RCMP officers embarked would continue, and reactive operations, such as counter-drug interdictions, would be carried out with the appropriate enforcement officers embarked.

Some argue that the Canadian Navy would not be qualified to undertake a more direct enforcement role, primarily because naval personnel are not conversant with the requirements of a court case. Essentially, this question involves training and shipboard organization. One solution would be to confer peace officer status on all watch-keeping officers, as well as a small cadre of sailors.22 These people would train specifically for law enforcement duties, and would become the ship’s experts with respect to the use of force, the care and custody of evidence, and other related matters. The logical choice for these teams would be the personnel who form the navy’s existing naval boarding parties. At present, naval boarding party team training is very similar to, but shorter than, that received by Canadian police officers, and it would require minimal adjustment to cater to at-sea enforcement requirements. It would mainly entail becoming familiar with the minimal number of federal statutes that would be enforced by the navy, and to ‘top up’ the team’s legalistic understanding of requirements for court.23

In the end, there is little doubt that the navy could execute an enhanced enforcement role, given its considerable experience in maritime interdiction operations abroad. Whether it will be given the chance to do so remains an open question.

Conclusions

Policing Canada’s maritime zones and approaches presents no shortage of difficulties to overcome, particularly as the federal government struggles to allocate finite resources to a plethora of ministries charged with maintaining national security. While the navy has always had a major part to play in protecting Canadian sovereignty, the burden of law enforcement has fallen largely upon other government departments. This reality reflects a Canadian tradition of law enforcement by civilian agencies. However, in light of the evolving post-9/11 asymmetric security environment, there is a case to be made for expanding the naval role in domestic maritime enforcement. Influenced to a degree by land-oriented aid to civil power operations, detractors question the legitimacy of this use of armed forces or denounce the idea as non-traditional. However, none of these issues presents an insurmountable obstacle to developing an enhanced role for Canada’s naval forces.

With federal enforcement departments becoming increasingly reliant on naval assets for support of their operations, the navy’s significant presence in Canada’s maritime zones should be leveraged, and the Canadian Navy, empowered with appropriate legal authority, should be granted the option to enforce Canadian law in those vast areas. Doing so would be yet another important step in realizing the goals articulated in Canada’s national security policy. Specifically, that entails the provision of maritime security to Canadians in an effective integrated manner.

![]()

Captain Hickey is both Commander Fifth Maritime Operations Group and Deputy Commander Canadian Fleet Atlantic.

Notes

- Canada, Report of the Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence. Canada’s Coastlines: The Longest Under-defended Borders in the World. October, 2003. pp. 108-109.

- Presence is essential in a vast Atlantic EEZ of 1.4 million km2 where, for example, it was estimated that 534 fishing vessels and 1137 merchant vessels were operating in March 2005.

- All maps were produced from the author’s data, with the assistance of GIS technicians Roxanne Gauthier and Richard Mayne, as well as graphic artist Ralph Lang.

- E.C.S. Wade and A.W. Bradley, Constitutional and Administrative Law (London: Longman, 1985), p. 406.

- Aid to the Civil Power is a type of domestic operation in which military forces are called out to suppress a riot or disturbance of the peace because it is beyond the civil authorities to control. The four instances are: 1969 Montréal Police Strike; 1970 FLQ crisis; 1976 Alberta sniper; and 1990 Oka crisis.

- Speech by Superintendent A. Antoniuk to RCMP officers at RCMP Training Academy, Regina, Saskatchewan, 27 September 1990; Desmond Morton, Understanding Canadian Defence (Toronto: Penguin, 2003), p. 158.

- Sean M. Maloney, “Domestic Operations: The Canadian Approach,” Parameters (Autumn, 1997), pp. 135-152.

- Matthew Carlton Hammond, “The Posse Comitatus Act: A Principle in Need of Renewal,” Washington University Law Quarterly 75 (No. 2, Summer, 1997) <http://law.wustl.edu/WULQ/75-2/752-10.html#fn160>, accessed 6 February 2005.

- Constitution Act, 1867, s. 91, s. 92.

- Elizabeth Young, “Policing Offshore: Civil Power or Armed Forces,” RUSI Journal 122 (No. 2, June 1977), pp. 18-22.

- Peter T. Haydon, Canadian Naval Future: A Necessary Long-Term Planning Framework, IRPP Working Paper 2004-12 (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy, November 2004), pp. 13-14.

- Peter T. Haydon, “What Naval Capabilities Does Canada Need?” in Maritime Security in the Twenty-First Century: Maritime Security Occasional Paper No. 11, E.L. Tummers (ed.), (Halifax: Dalhousie University, December 2000), p. 157.

- Gary L. Garnett. “The Navy’s Role in the Protection of National Sovereignty.” In An Oceans Management Strategy for the Northwest Atlantic in the 21st Century: The Niobe Papers; Volume 9, Peter T. Haydon and Gregory L. Witol (eds.), (Halifax: The Naval Officers Association of Canada, 1998), p. 11; Young, “Policing Offshore,” pp. 18-22.

- Colin S. Gray, Canada’s Maritime Forces: Wellesley Paper 1 (Toronto: Canadian Institute of International Affairs, January 1973), p. 46.

- Canada, Department of National Defence, Leadmark: The Navy’s Strategy for 2020 (Ottawa: Directorate of Maritime Strategy, 2001), pp. 43-45.

- Michael A. Morris, “Military Aspects of the Exclusive Economic Zone,” in Ocean Yearbook 3 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1982), p. 336.

- Testimony of John F. Thomas before the Senate Committee on National Security and Defence, Issue 19, Evidence Morning Session 9 June 2003.

- Canada, Privy Council Office, Canada’s International Policy Statement (Ottawa: 2005), p. 12.

- Michael Pugh, “Policing the Seas: The Challenge of Good Governance,” in The Role of European Naval Forces after the Cold War, G. de Nooy (ed.), (Netherlands: Kluwer Law International, 1996), pp. 105-111; Michel d’Oléon, “Policing the Seas: The Way Ahead,” in The Role of European Naval Forces after the Cold War, G. de Nooy (ed.),(Netherlands: Kluwer Law International, 1996), p. 144.

- Craig T. Trebilcock, The Myth of Posse Comitatus, October 2000, <http://www.homelandsecurity.org/journal/articles/Trebilcock.htm>, accessed 6 February 2005.

- Michael R. Adams, “Navy Narcs,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings (September 1984): pp. 35-37.

- This idea was proposed as a means of preparing the Canadian Coast Guard for constabulary duties. See testimony of John F. Thomas before the Senate Committee on National Security and Defence, Issue 19, Evidence Morning Session 9 June 2003. See also Canada, Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans. Safe, Secure, Sovereign: Reinventing the Canadian Coast Guard. March 2004, p. 48.

- Based upon author’s experience and training as a former member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.