This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Intelligence

Worldnews photo

A significant new security threat – Islamic fundamentalists.

Has the Time Arrived for a Canadian Foreign Intelligence Service?

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

“Maybe we have to wait for a crisis and [then] we will be caught with our pants down sometime and we will say ‘Jesus, aren’t we a stupid bunch of people. We didn’t have any information on that [issue] and no way of getting it.’ That’s probably what it will take.”1

Canada is in the enviable position of being a technologically advanced, prosperous and safe country. It is rich in natural resources and portrayed as a tolerant, welcoming nation where people from around the world come to visit, work and, for some, settle. For many years, Canada – the peaceable kingdom – was considered by the United Nations (UN) to be the best country in the world. Despite such an optimistic viewpoint about this country, the world in which we live is a volatile place beset by competition for scarce natural resources, demographic change, the effects of globalisation, the rise of religious extremism, asymmetric warfare, and the reach – as well as constraints – of US global power. In the last 15 years, the global security framework has shifted from a bipolar one based on the Cold War, to a multi-polar one following the collapse of the Soviet Union, to a distinctly unipolar one dominated by the United States (US) “[possessing] unprecedented and unequalled strength and influence in the world,” coupled with “unparalleled responsibilities, objectives and opportunity.”2 Closer to home, a number of well-known terrorist groups have established an active presence in Canada, “virtually all of them relating to ethnic, religious or nationalist conflicts elsewhere in the world”.3 These include Al Qaeda, Hezbollah, Hamas, Al-Jihad, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), among others.4 The World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, coupled with recent inquiries, mean that Canadians can no longer continue to believe that this country is immune to terrorist activity within its borders, posing a threat to Canadian security and interests at home and abroad.

The Government of Canada requires information and intelligence data to make reasoned and sound decisions on behalf of Canadians. To achieve this aim, the government needs access to information from a variety of sources. There are many potential sources for this information – from open sources, highly classified ones, and information gathered by human sources. As the late Geoffrey Weller has pointed out, “[t]o assume that a society will not seek secret means... to defend itself is unrealistic.”5 In the 21st Century, inter- and intra-state conflict, non-state actors, the proliferation of sophisticated weaponry and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) have converged to change the nature of the global environment dramatically. Moreover, as manifested in the international debate over WMD and terrorism in Iraq and Iran’s nuclear ambitions, this environment has strengthened a continuing need for independent, objective and balanced Canadian intelligence advice to policymakers, military commanders and the government. Indeed, Operation Barbarossa during the Second World War, the Yom Kippur War, the Falklands Campaign, the UN Mission in Rwanda (Operation Assurance for the Canadian Forces), and the human intelligence (HUMINT) sources, which lead to the capture of Saddam Hussein all point to the importance, benefits and pitfalls of intelligence derived from human sources. One means to achieve such an in-depth level of knowledge is via a foreign intelligence service that operates on the basis of collecting intelligence principally from human sources. Ironically, there is a historical reluctance to accept the fact that intelligence in its broadest sense is an essential part of Canadian government decision-making.6

As an intelligence discipline, HUMINT is among the most important collection categories used in operations. While other disciplines – such as imagery intelligence (IMINT), and signals intelligence (SIGINT) – are also important contributors and attract considerable atten tion, they cannot pro vide important information concerning “local attitudes, emotions, opinions, identities and importance of key players, and their inter- relationships...”7 Moreover, “HUMINT can:

- provide early warning;

- provide understanding of [another nation’s] population that reveals attitudes and intentions of individuals, factions, [and] hostile forces;

- reveal direct and indirect relationships (political, financial military, criminal– even emotional) among key players; and

- indicate HUMINT activities [conducted against Canadian intelligence organizations].”8

Aim

The aim of this article is to demonstrate that the 21st Century security environment and government information and intelligence requirements are sufficiently intricate and demanding that the time has come for Canada to establish a foreign intelligence service.

Scope

In developing this service we will examine the following issues:

- the “new” Canadian intelligence community, in order to place the activities of the national intelligence machinery in context;

- the historiography of intelligence in Canada; and

- the ‘pros and cons’ of a foreign intelligence service.

Definitions

Ironically, no government-agreed definition of intelligence in Canada exists. Therefore, in the interests of clarity and consistency, the following definitions will be used throughout:

Intelligence is “the product resulting from the processing of information concerning foreign nations, hostile or potentially hostile forces or elements or areas of actual or potential operations. The term is applied to the activity which results in the product and to the organization engaged in such activity.”9

Security Intelligence is “intelligence on the identity, capabilities, and intentions of hostile organizations or individuals who are, or may be, engaged in espionage, sabotage, subversion, terrorism, criminal activities or extremism.”10 Typically in Canada, security intelligence is “collected to help maintain public safety and protect national security.”11

Foreign Intelligence is intelligence data about the “plans, capabilities, activities or intentions of foreign states, organizations or individuals. It is collected to help promote as well as to safeguard national interests.” More importantly, foreign intelligence “need not have a threat component.”12

The Canadian Intelligence Community

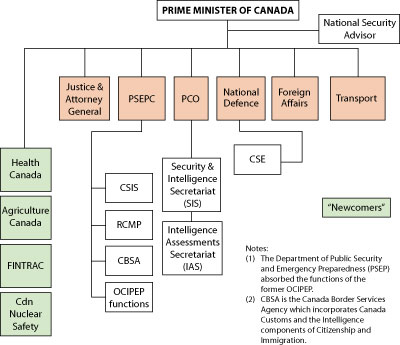

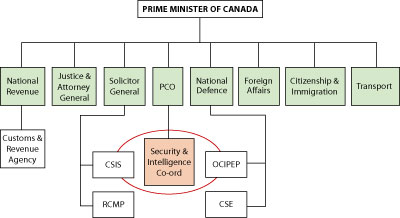

Figure 1 depicts the Canadian intelligence community, as it existed prior to 12 December 2003. The principal departments and agencies at the time were the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), the Department of National Defence (DND), and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

Figure 1 – Principal Canadian Departments and Agencies with Security and Intelligence Roles – Prior to 12 December 2003.

After 12 December 2003, however, there were significant changes that Prime Minister Paul Martin put into effect immediately upon taking office. They are depicted in Figure 2.

Note the strengthening of the Public Safety portfolio, and the establishment of the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). This arrangement validates the requirement for a more integrated approach to the Government of Canada’s intelligence community. Another important development was the creation of the post of National Security Advisor (NSA),13 and his role will continue to evolve, particularly as the 2004 National Security Policy implementation, and the 2005 International and Defence Policies take shape. While some details and procedural issues remain to be worked out, such as to whom the NSA reports and his working relationship with the Deputy Minister at Public Security and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC), the Foreign and Defence Policy Advisors, and the Clerk of the Privy Council, the current intel ligence community is more representative of the producers and their clients. This situation is driven, in part, by a broader view of security than has been the case in the past, as well as by the realities of 21st Century intelligence requirements.14 That said, these very practical changes drive hard against the gener alized view of intel ligence and its place in Canadian political culture. The quotations below set the scene for the discussion of Canadian intelligence historiography:

“With remarkable stealth, [then-Prime Minister] Paul Martin developed... a surprising and ambitious security agenda.”15

“At the political level in Canada, there has been little interest in utilizing intelligence as a regular tool to assist decision-making.”16

“Until recently, [intelligence] has played no role whatsoever in public discus sion of foreign, defence and security policy.”17

However, the question that begs expression is: “Why has intelligence not played a more overt role in our national past?”

The Historiography of Canadian Intelligence

As Geoffrey Weller has written, for a country with a small intelligence establishment, Canada has “produced quite a sizeable literature on such matters.”18 Regrettably, in the first instance, the ‘lion’s share’ of this literature has been related to security intelligence, overly focused upon oversight and accountability, and fixated upon the circumstances surrounding RCMP wrongdoing and the resultant McDonald Commission.19 The Commissioner’s ultimate finding that the “university study of intelligence is, indeed, quite healthy in Canada,”20 is somewhat overstated when one considers the all-source intelligence dimension. First, while there have been many improvements – generated through intelligence studies conducted at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University, the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary, the Centre for Conflict Studies at the University of New Brunswick, and the War Studies program at the Royal Military College of Canada – much work needs to be done to improve Canadians’ knowledge of the national security and intelligence community.21 Second, continually portraying intelligence as somehow unsavoury, ‘stealthy’, or trampling on the rights of Canadians does not contribute to an informed debate on the issues at hand. Nor, until recently, would senior officials discuss serious security and intelligence issues, except when responding to a scandal, typically involving CSIS.22 To exacerbate this weakness, public policy groups have paid virtually no attention to security and intelligence matters. Third, continually portraying CSIS or CSE as the ‘intelligence community’ is unhelpful, and it does not acknowledge the contributions of other departments, such as Health, Agriculture and Agri-Food, Finance, and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). Nor does it acknowledge the importance of economic issues.23 Fourth, there has been precious little engagement at the political level writ large, although there is evidence suggesting greater need for further intelligence collection, particularly abroad.24 Fifth, it must be said that the intelligence community bears some responsibility for this lack of knowledge, as it is the community’s responsibility to brief fully those in positions of power with respect to the capabilities and limitations of the intelligence community as a whole. However, this presents a challenge when dealing with an unreceptive or disinterested audience. Suffice it to say that all these conditions cloud the discussion of establishing a foreign intelligence agency. Finally, only very recently has Canada developed any form of national security framework – one that clearly articulates our national interests – based upon a clear understanding of what actually constitutes ‘national security’, where domestic and international interests would be compared against the global security environment as assessed in, for example, the United Kingdom’s excellent strategic survey, entitled Strategic Trends. This Canadian National Security Policy (NSP) document allows for clear linkages between the government’s ‘3-Ds’ – defence, diplomacy and development – approach, and the world in which Canada finds itself situated. These links facilitate the development of intelligence collection strategies that would employ a foreign intelligence agency, in concert with other collection disciplines.

Prior to the promulgation of Canada’s NSP, which was released with great fanfare on 27 April 2004, Canada essentially totally lacked a national security framework. Indeed, it is true to say that Canada lacked “any process even remotely comparable [to the United States and the United Kingdom] in analytical vigour, multi-department involvement, coherence and consistency.”25 From the American and the British planning communities, the US published its National Security Strategy, the UK its British Defence Doctrine Strategic Trends, as well as Active Diplomacy for a Changing World: The UK’s International Priorities.26

Canada’s NSP achieves this aim by laying out Canada’s national security interests:

- protecting Canada and Canadians at home and abroad;

- ensuring Canada is not a base for threat to our allies; and

- contributing to international security.

In addition, Canada’s core values are defined as democracy, human rights, respect for the rule of law, pluralism, openness, diversity and respect for civil liberties.27 Thus, for the first time, Canada’s national security framework is relatively concise, the success of which is predicated on a sound intelligence base.

That said, additional work remains to be done vis-à-vis the NSP, as the policy does not differentiate sufficiently between threats (security) and hazards (public safety), since not everything is, in actuality, a threat, even though it is so designated.28

Previous Discussions

As Alistair Hensler – a former Assistant Director of CSIS – has pointed out, the issue of a foreign intelligence service in Canada has been discussed at various stages since at least 1945. For example, a former post-war Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes, proposed the establishment of a ‘National Intelligence Organization’. The aim of the proposal was to “consider means for advancing the efficiency of resources of intelligence relating to Canada’s National interest.”29 His paper on the subject highlighted the importance that assessments, to be effective, “must be from a national viewpoint,” due to the growth of “Canada as a World Power [after the Second World War, which demanded] an independent appraisal of world affairs.”30 Furthermore, he went on to state that “[a]ny system whereby the [assessment] is made from incomplete intelligence acquired from other countries, or the acceptance of another nation’s [assessment]... cannot possibly satisfy the Canadian requirement. Such a system would presuppose a degree of political, economic and military dependence incom mensurate with the national outlook.”31 This view would be echoed 20 years later in an article raising a concern that Canada’s Joint Intelligence Bureau was too dependent on the Americans and the British for its intelligence data.32 Foulkes’s paper then added that, while the issue of whether Canada should have a foreign intelligence service was a “matter of high policy,” such an organization could be added to the proposed Joint Intelligence Bureau.33 Yet, the evidence also suggests that the issue of a foreign intelligence service “[has never been] studied in a comprehensive way” by the bureaucracy and the concept, therefore, “[has never been] presented to ministers.”34 However, a number of reasons caused this situation, including a lack of broad national intelligence experience, the repugnance generated toward intelligence and espionage resulting from the Gouzenko affair in 1945 – and to a singular dislike generated for US intelligence organizations of the time, notably the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Such myopic and naïve views, coupled with the “intransigence of the personalities who were setting [security and intelligence] policy,”35 have stunted serious debate and examination of the ‘pros and cons’ of foreign intelligence collection for the past 60 years.

PA-129625

Igor Gouzenko, the Soviet defector who in 1945 revealed a Russian spy net in Canada, was hooded for his own security against communist vengeance.

The ‘Pros and Cons’ of a Foreign Intelligence Service

As previously mentioned, the idea of a foreign intelligence service has been discussed at great length since the end of the Second World War. Ironically, this writer’s research shows that while many academics – present and former practitioners (Starnes, and – eventually – Hensler and Stafford) – support a foreign intelligence agency, the bureaucracy has traditionally opposed it (including George Glazebrook and Norman Robertson at the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT)).36 In addition, the political level has not been engaged, and, in reality, no serious in-depth study available in the public domain examining all of the issues has ever been conducted.

The ‘Pros’

First and foremost, Canada would achieve greater independence in foreign policymaking, especially in the economic field, and such policymaking should be based upon independently collected data. Second, as area expert analyst Finn points out, “[the] most compelling argument of all, but one that does not often make the pages of reports, is that in a crunch our friends may conduct foreign intelligence operations against us, particularly in the economic and trade arenas.” His deduction is that Canada should not only be able to counter such collection operations, but “pursue them for our own ends.”37 Indeed, other experts in the field discuss the importance of economic intelligence extensively.38 Third, a foreign intelligence agency would alleviate Canada’s continued dependence upon intelligence produced by our partnerships and allies. Moreover, we would assess our own raw data based on Canadian requirements – current and future intelligence data needs versus any Allied finished intelligence products that they are willing to share. And they do not share everything. In addition, such finished intelligence can reflect a producing nation’s bias. The Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs (SCONDVA) opined that “[c]ooperation with our allies is essential and productive, but (Canada) would be foolhardy to assume that [they] always view events through the same lens as we do or their national interests are always in harmony with ours.”39 Fourth, there are potentially significant quid pro quo benefits, as intelligence remains a highly personalized effort, and independently collected and analyzed intelligence is a good bargaining chip, especially with non-traditional intelligence allies. Fifth, there is significant potential to improve overall governmental situational awareness, and, thus, its ability to ascertain an adversary’s inner secrets. Sixth, a legislative framework for the entity already exists, with both the CSIS Act and David Pratt’s Private Member’s Bill, C-409, An Act to Establish the Canadian Foreign Intelligence Agency.40 Current and former directors of CSIS point out that the CSIS Act already authorizes the Service to conduct operations abroad – likely under the aegis of Section 12 of the Act – and 21st Century events have “increasingly required [CSIS], as was envisaged by those who designed the Act, to operate abroad.”41 Additionally, Anne McLellan’s speech in March 2004 specifically stated that Canada “must continue to enhance [its] capacity to collect [intelligence] abroad.”42 According to Elcock, the result is: “working covertly abroad has become an integral part of the Service’s operations.”43

Worldnews photo

Members of the Islamic Jihad fire missiles towards the Israeli town of Sderot near the Gaza Strip, 31 May 2006.

The ‘Cons’

Establishing a foreign intelligence service would not be without its challenges. First, it would appear that the bureaucracy and elements of governmental leadership remain sceptical of the benefits of such a capability. This is due to a prevailing view that because Canada’s intelligence needs “are being met by current arrangements,”44 there is no requirement for a foreign intelligence agency. Second, it would be overcoming a ‘Johnny Canuck come lately’ perception vis-à-vis the more experienced agencies, namely the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the British Secret Intelligence Service (BSIS), and the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), just to name a few. In such an important business, inexperience can compromise sources and embarrass both the organi zation and the parent nation. The key to success will be recognizing that such a capability cannot be created overnight; it must be implemented via an incremental approach, and expectations must be managed accordingly. Third, there is a view that having such a capability will somehow result in a loss of Canada’s reputation abroad, based upon, inter alia, a ‘balanced approach’ in the Middle East, or ‘constructive engagement’ in other regions, or being a ‘helpful fixer’ by promoting peace, order and good government. Such a view is a fallacy perpetuated by successive governments of both political persuasions unwilling to conduct a serious study of Canada’s national security interests until the present. Truth be told, the reaction on the part of the broader international community could enhance our global standing, as others would applaud Canada’s efforts to wean itself from its intelligence dependence, thus enhancing national information sovereignty.45 Fourth, while it can be argued that other vehicles for intelligence collection exist (diplomatic posts, Canadian Defence Attachés, SIGINT and interview programs, and increased use and access to open sources), in the post-Cold War asymmetric world in which we live, the old intelligence arrangements are no longer sufficient, and making foreign policy decisions without applying all sources is most unwise. Finally, the issue of cost is continually raised as a reason not to establish a foreign intelligence service, rather than as a factor in establishing a capability for which the government has validated the requirement. Depending on the source, estimates vary from $10 million (Hensler) to $20 million (SIRC) to $60 million (Starnes); however, no serious analysis has ever been conducted. Thus, while cost is an important factor, even at the upper range, $60 million is, in the grand scheme of things, relatively modest, and certainly not a significant impediment when compared to the billions of dollars the federal government spends on other activities of lesser demonstrable return.

Conclusion

The issue of a Canadian Foreign Intelligence Service has been discussed – on and off – for at least the last 60 years. As is often pointed out, Canada is one of very few Western powers not to have such a capability. That fact, in and of itself, should not be the primary determinant of whether Canada should have a foreign intelligence service. The reality, however, is that the world has changed, the concept of national security has changed, and, therefore, Canada’s intelligence needs have also changed. While the issues outlined above are significant, others remain. They include a clear mandate; clearly articulated collection requirements benchmarked against that mandate; procedures and protocols; recruiting and training; reliable analysis of costs (personnel, infrastructure, equipment), and so on. Therefore, such a service cannot be created overnight, and a five-to-ten-year period required to reach a high level of proficiency cannot be ruled out. Indeed, it took CSIS 20 years to evolve to what it is today. In addition, there is broad ‘whole-of-government’ recognition that we cannot continue to rely upon finished intelligence produced by other nations, particularly in the HUMINT realm. As mentioned earlier, HUMINT can, in concert with other sources, contribute significantly toward revealing and understanding attitudes of individuals, organizations and governments, especially if that source has direct access to an adversary’s inner circle, or to senior government officials.46

In the modern era, Canadian government policymakers have suffered from a dependence on foreign-derived intelligence, collected to meet the needs and intelligence requirements of their country, versus our own. In strategic areas, notably national security, economics and trade, we abrogate our sovereign responsibilities by such reliance – particularly when assessing raw data based upon Canadian requirements, and current and future intelligence data needs versus the Allied finished intelligence products that they are willing to share. This country has, indeed, been very lucky, and whether Canada commits to combat or peacekeeping operations overseas, the government must have the tools at its disposal to make reasoned decisions, based upon Canadian informational sovereignty. The 21st Century asymmetric world is more complex and – critically – more nuanced and subtle than the bipolar Cold War construct. It is interesting to note material in the public domain that indicates the government is carefully laying the groundwork for a foreign intelligence agency.47 Finally, as the issue of the role of intelligence and WMD in Iraq has brought forth for Australia, the US and the UK,48 perhaps relying too much upon another nation’s intelligence data can be more harmful to the national interest in the long run than the ability to gather foreign intelligence independently. A foreign intelligence service for Canada, separate from CSIS and modest in size – perhaps based on the ASIS model – is, in the final analysis, in the national interest. Indeed, the spy novelist John le Carré summed it up as follows:

“Information is only the path.... The goal is

knowledge.”49

![]()

Lieutenant-Commander Parkinson, an Intelligence Officer, is J2 Plans of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Command in Ottawa.

Notes

- The Ottawa Citizen “Weighing the merits of a foreign intelligence service” 22 October, 1988, p. B6.

- United States of America. The National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 2002).

- Martin Rudner, “Contemporary Threats, Future Tasks: Canadian Intelligence and the Challenges of Global Security” in Horman Hillmer and Maureen Appel Molot, Canada Among Nations 2002: A Fading Power (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 145, quoting the CSIS 1997 Public Report.

- For the full list see “Listed [Terrorist] Entities” on the Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC) web page at <http://www.psepc.gc.ca>.

- Geoffrey R. Weller, “Accountability in Canadian Intelligence Services” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Vol. 2, No. 3, Autumn 1988, p. 415.

- Reid Morden, “Spies, not Soothsayers: Canadian Intelligence After 9/11”, CSIS Commentary #85, 26 November 2003. Also see Geoffrey R. Weller, “Assessing Canadian Intelligence Literature: 1980-2000” International Journal of Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence Vol. 14, No.1, Spring 2001.

- Canada, Department of National Defence, The Army Lessons Learned Centre. “HUMINT During Peace Support Operations”, Dispatches: Lessons Learned for Soldiers, Vol. 8, No.1, June 2001, p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Canada, Department of National Defence. Joint Intelligence Doctrine (B-GJ-005-200/FP-000) (Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada, 2003), p. GL-2.

- Canada, Department of National Defence. The Intelligence Analyst’s Handbook (2000 Edition), Chapter 1.

- Canada, Office of the Auditor-General of Canada. The Canadian Intelligence Community: Control and Accountability (Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada, November 1996), para 27.13, Hereafter cited as OAG.

- OAG. Also see Alistair S. Hensler, “Creating A Canadian Foreign Intelligence Service”, Canadian Foreign Policy, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Winter 1995), p. 16.

- The incumbent, in an acting capacity, is Stephen Rigby.

- The Honourable Anne McLellan, Speech delivered to the Canadian Club of Ottawa “Securing Canada: Laying the Groundwork for Canada’s First National Security Policy”, 25 March 2004, at <http://www.psepc.gc.ca>.

- Wesley Wark, “Martin’s new security agenda: Feeling safe yet?” The Globe and Mail, 18 December 2003, p. A25. Emphasis added.

- Morden.

- Anthony Campbell, “Canada-United States Intelligence Relations and ‘Information Sovereignty’” in David Carment, Fen Osler Hampson and Norman Hillmer, Canada Among Nations 2003: Coping with the American Colossus (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 159.

- Weller, “Assessing Canadian Intelligence Literature”, p. 4

- Weller, “Accountability in Canadian Intelligence Services”, p. 423.

- Weller, “Assessing Canadian Intelligence Literature” p. 50.

- Morden.

- The Arar and Kawaja cases are but two examples of this phenomenon. Also see David Pratt “Does Canada Need a Foreign Intelligence Agency?”, March 2003, p. 23.

- Weller, “Assessing Canadian Intelligence Literature”, pp. 54,56. One exception is Martin Rudner, “Contemporary Threats, Future Tasks: Canadian Intelligence and the Challenges of Global Security” in Horman Hillmer and Maureen Appel Molot, Canada Among Nations 2002: A Fading Power (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp 141-171.

- McLellan speech, 25 March 2004.

- W. Don McNamara and Ann Fitz-Gerald. “A National Security Framework for Canada” Policy Matters Vol. 3, No.10, October 2002, pp. 20-22.

- United States of America. The National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 2002 and 2006), United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, British Defence Doctrine, and United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, and the Joint Doctrine and Concepts Centre (JDCC), Strategic Trends (JDCC, Swindon: March 2003), and Active Diplomacy for a Changing World: The UK’s International Priorities (London: The Stationery Office, 28 March 2006). Also, see The Presidential Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction.

- Canada. Privy Council Office, Securing an Open Society: Canada’s National Security Policy (hereafter NSP) (Ottawa; Department of Supply and Services, 27 April 2004), Letter of Promulgation, and p. vii., at <http://www.pco-bcp.gc.ca/docs/Publications/NatSecurnat/ natsecurnat_e.pdf>.

- Ibid., particularly Chapter 1, pp 6-8.

- Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes. “A Proposal for the Establishment of a National Intelligence Organization”, Library and Archives Canada, RG 2, Vol. 248, File I-40 (1945-47).

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Ibid. Emphasis added.

- John Davis, “Canada’s JIB Depends on [the] US., U.K. For Intelligence Data”, The [Montréal] Gazette, 25 April 1966.

- Foulkes, p. 3.

- Alistair S. Hensler, “Creating A Canadian Foreign Intelligence Service” Canadian Foreign Policy Vol. 3, No. 3 (Winter 1995), p. 20.

- Hensler, p. 21.

- For the latter, see Ibid., pp. 17-21.

- Finn, p. 159.

- Notably Samuel Porteus, “Economic Espionage”, CSIS Commentary #32, May 1993; “Economic/Commercial Interests and Intelligence Services” CSIS Commentary #59, July 1995.; “Economic Espionage (II)”, CSIS Commentary #46, July 1994; and Evan H. Potter, (ed). Economic Intelligence and National Security (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1998).

- Canada, House of Commons, Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs, Facing Our Responsibilities: The State of Readiness of the Canadian Forces (Ottawa: House of Commons, May 2002).

- See <www.parl.gc.ca/37/2/parlbus/chambus/house/bills/

privtae/c-409/c-409-1/c-409-cover-e.html>. - See Ward Elcock. John Tait Memorial Lecture, presented to the Canadian Association for Security and Intelligence Studies, 16-18 October 2003, Vancouver, British Columbia. Emphasis added. Also see Morden.

- McLellan.

- Elcock. The discussion of whether a foreign intelligence organization should be an integral part of a security intelligence organization (i.e., CSIS) – akin to combining MI-5 and MI-6 or the FBI and CIA – is a separate issue, and most analyses do not favour such an arrangement. However, the requirement for a Canadian human sources-based foreign intelligence collection service is valid.

- SIRC Counter-Intelligence Study 93-06, p. 9.

- For a discussion of information sovereignty and its relation to foreign intelligence collection, see Campbell.

- See the speech by former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency George Tenet to Georgetown University 5 February 2004, at <http://www.cia.gov>.

- McLellan, and the NSP, Chapter 3.

- For example, the Government of Australia decided that there should be an independent assessment of the performance of the intelligence agencies, announced by Prime Minister John Howard on 4 March 2004. In addition, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on ASIO, ASIS and DSD prepared a report on Intelligence concerning Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction, available at <http://www.aph.gov.au/house/ committee/pjcaad/WMD/Index.htm>. A further report was prepared by Philip Flood. See Report of the Inquiry into Australian Intelligence Agencies (Canberra: 20 July 2004) at <www.pmc.gov.au/publications/ intelligence_inquiry/index.htm>. In the UK, the Foreign Secretary announced an inquiry in the House of Commons on 3 February 2004, chaired by Lord Butler of Brockwell, formerly the Cabinet Secretary, and it included a former Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), Field-Marshal Lord Inge, and Ann Taylor, the Chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC). See “Key facts: Iraq intelligence inquiry” at <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/3455555.stm>, and the full report, Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction, 14 July 2004), at <www.butlerreview.org.uk>. For the US inquiry, see “Bush orders intelligence review” at <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/ world/middle_east/3450151.stm>, and the Presidential Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction (the Silberman Commission).

- John Le Carré, Absolute Friends (Toronto: Viking Canada, 2003), p. 28.