This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Other Places and People

DND photo HS048069d02 by Corporal Matthew McGregor, Formation Imaging Services Halifax

A CH-146 Griffon Helicopter from 430 Squadron flies over the Presidential Palace in the heart of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as part of Operation Halo.

The Case for International Trusteeship in Haiti

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Author’s Update

During the 12 months since this article was initially penned, the situation in Haiti has improved somewhat. There have been multiple rounds of elections, and the new government headed by René Préval has enjoyed some early successes. However, only time will tell if these early signs of success will last, and if Haiti will overcome the multiple challenges it faces. Readers should be aware that although this article was written before the November 2005 elections, it has been left in its original state, due to present political/social dynamics and concerns, as well as to the history of the region. I would argue that the main contentions and concerns expressed herein are still valid.

Introduction

In the past 12 years, the United Nations has authorized five separate missions to Haiti, each one varying in scope, goals, and resources. It is not unreasonable to state that each of these missions has failed to fulfil its mandate. The current United Nations mission, la Mission des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en Haiti (MINUSTAH), has a very wide-ranging mandate, authorizing the international community to pursue an extensive menu of responsibilities and tasks. This list is largely reflective of current thinking on the ways and means that post-conflict societies can be rebuilt, and then set upon a course to a brighter future. However, MINUSTAH’s mandate, issued in April 2004, has a focus very similar to that of the mandate for the first United Nations military mission to Haiti, issued in 1993. That first mission, the United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH), was charged with establishing a secure and stable environment, with creating a police force separate from the army, with supporting free and fair elections, and with providing further urges to the international community to support the economic, social, and institutional development of Haiti.1 MINUSTAH is charged with, among other things, establishing a secure and stable environment, reforming the Haitian national police, assisting with disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR), assisting with the establishment of rule of law, fostering institutional strengthening and the principles of democratic governance, national dialogue and reconciliation, assisting with free and fair elections, and extending state authority throughout Haiti.2 The more precise language used in the MINUSTAH mandate aside, the similarity of the two mandates is striking. This similarity, and a brief examination of the current state of disorder in the nation, may lead the reader to conclude that the United Nations, and, by extension, the international community, has not yet achieved what it set out to do in Haiti 12 years ago.

This article will attempt to explain why such has been the case. What is the international community trying to achieve in Haiti? What are the assumptions and logic underlying these efforts? Is this a sound approach, and what could be done differently to address the root causes of the nation’s problems more appropriately?

It will argue that the current UN mission is inadequate, and will not succeed without profound changes in both its scope and nature. The critical underlying problem in the country is the chronic lack of legitimacy endemic to the Haitian state, which must be addressed before any long-term peace can be established in the country. Further, the United Nations’ “strong commitment to the sovereignty [and] independence ... of Haiti”3 is a crucial barrier to the international engagement required to rebuild and reform the Haitian state, such that it becomes comfortable within the international community of nations. It will be argued here that the proper solution for the problem of Haiti is creation of an international trusteeship, one that will allow for the institutions of the Haitian state to be rebuilt and to be made effective, prior to transition, under international stewardship, to a fully self-directed democratic state with an effective market economy.

However, it is acknowledged that the intervention/ trusteeship solution has been attempted before in Haiti, and it has failed. The long history and unique culture of this country have given the Haitian people a strong sense of independence and nationhood. This poses a considerable challenge to the international community – to develop and implement an approach that will be perceived as legitimate by the Haitian nation, and not one simply imposed by outside powers.4

The article will open with a brief review of the current state of affairs in Haiti – the economic, social and political facts that must be considered in any peacebuilding effort. It will then undertake a theoretical examination of what is reasonable or desirable to try to achieve in that state; what is peace, how can it be achieved, and what should be the international goals for peacebuilding in Haiti. With these benchmarks established, it will turn to a consideration of the particularities of the Haitian case, the history, culture, and political climate that factor into any proposed solution. Finally, it will consider the issue of the current approach of the international community to Haiti, to match the mandate of MINUSTAH against the requirements of peacebuilding in that state, to examine the underlying logic of the approach, to describe points of weakness, and to make recommendations for the future course of the mission.

CMJ map by Monica Muller

Current Conditions – Political

The Economist Intelligence Unit, in its February 2005 country report, described Haiti as a country with severe and continuing political and economic problems.5 Politically, the Fanmi Lavalas party of former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide stated that it would not contest elections scheduled for November 2005, calling into question this latest effort to build some form of a popularly legitimate and stable government. Troops deployed to Haiti as part of MINUSTAH were unable to provide a safe and secure environment for the citizens of the country. Violence continued to be widespread, but was most especially concentrated in the poorer slums of Port Au Prince, and that violence was symptomatic of the failure of the interim government to achieve any kind of reconciliation with the supporters of the former president.6 There were also large portions of the interior of the country outside the effective control of the central government.

DDR efforts were stalled, with no effective program of disarmament being put in place.7 The former army was re-emerging as a political force, with members of the Forces Armées d’Haiti (FAd’H), which was disbanded in 1995, organizing to demand reinstatement of the army, and payment of pensions and back pay.8 Former army officers were also providing de facto security in some areas of the interior of the country.9

Flag of Haiti

Current Conditions – Economy and Society

The state of the Haitian economy continues to be extremely poor. GDP declined by 3.8 percent from 2003 to 2004, and, despite a restart of external assistance, the government faces large external debt repayment obligations, as well as many competing priorities for investment and spending.10

The socio-economic situation of the majority of the population of Haiti is also deplorable. Amnesty International reports that Haiti continues to be the poorest country in the Americas, with a human development ranking of 150 out of 173, and a life expectancy of just 49.1 years. The United Nations Development Program states that food insecurity affects some 40 percent of households, and that more than 50 percent of the adult population is unemployed.11

Finally, the lack of effective political control throughout the nation has increased opportunities for criminal actions. Over the past several years, Haiti has become a focus for Central American drug cartels seeking alternate trafficking routes into North America.12

Importance of the Situation to Canada

This situation of poverty, political instability, and criminality is not unique in the world, but it has a particular salience for Canada. This country has long claimed a special relationship with Haiti, and it hosts a considerable portion of the Haitian Diaspora, mostly resident in Montreal. Further, there is a danger that existing but currently weak relationships between Haitian criminal gangs in Montreal and criminal organizations in Haiti might develop into a robust and well-structured system bolstered for the importation of illegal narcotics over the medium to longer term.13 Haiti’s geographic position is also unique amongst contemporary failed or failing states with respect to its proximity to the North American continent, particularly to the United States, and also with respect to the ability of Haiti’s domestic crises to directly influence the political discourse of the US. All these factors combine to exert considerable pressure upon Canada, both internally and with reference to its relationship with the US, to engage effectively in Haiti, both directly and through the offices of the United Nations.14

Start with the Ends in Mind

Of course, the major question that Canada should answer prior to embarking upon any intervention into Haitian affairs is what it is that has to be accomplished. What does the peace that one is trying to build look like, and how does one go about building that peace? There are a wide variety of voices and positions on what peace is, how it can be achieved, and how to measure it. Daniel Byman, although specifically discussing ethnic conflicts, takes the position that a conflict is terminated successfully when deaths attributable to the conflict in question fall below 100 per year for a minimum of 20 years.15 This is certainly a strong and satisfying measure of peace, and a post-conflict state that achieves this measure would likely have effectively mitigated the challenges that led to the conflict in the first place. However, as a guide to a course of action, it does not suggest anything specific, although it does perhaps give the next generation a tool by which it might wish to measure success. Roland Paris, in At War’s End, uses a less rigorous definition to describe what it is one wishes to achieve, speaking of “a peace that will last beyond the departure of the peacebuilders themselves and into the foreseeable future.”16 While less precise, this definition is perhaps a better guide for how to approach the problem of Haiti, as it forces the policymaker to consider how to ensure the peace after the departure of the peacekeepers. Fen Hampson expands upon this theme, describing the measure of success of the peacebuilding process as “directly related to a society’s ability to make the transition from a state of war to a state of peace marked by the restoration of civil order, the re-emergence of civil society, and the establishment of participatory political institutions.”17 An examination of the mandate of MINUSTAH would suggest that the UN is aiming for a comparable solution, and this will be discussed in more detail later in the article.

However, while Hampson’s description is compelling, it is not sufficient. There is no doubt that order must be restored, and civil society must re-emerge, but this definition does not address the effectiveness of the civil society, and the institutions that the society has established. Does the society perceive the institutions as effective? Are political disputes resolved through these institutions? And are they operating for the greater good, as opposed to serving the needs of a narrow minority?

DND photo IS2004-6056

Soldiers of the Second Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment (2RCR), take a moment to survey their position during a foot patrol in the city of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as part of Operation Halo.

Necessary but Insufficient Conditions

Specific to the case under consideration, Haiti very much resembles Hampson’s description – that is, not lacking for the outward appearance of democratic life. The 1987 constitution, drafted in the wake of the departure of the Duvaliers, and the last of two dozen Haitian constitutions adopted since 1804, was created by an elected constitutional assembly comprised of a large number of civil society groups drawn from all levels. It was adopted by a national vote with a 99.8 percent approval rating by 50 percent of eligible voters. It was a thorough document, with a far- reaching vision for a more just, equitable, and democratic state, based upon respect for individual rights and freedoms.18 Indeed, the constitution embodied many, if not all, of the concerns of the international community as they were reflected in the MINUSTAH mandate. However, despite the open and democratic nature of the process of the development and adoption of this constitution, the civilian president was overthrown in a coup d’état the following year, and Haiti returned to dictatorship under military rule. Evidently, the civil societies, and the participatory political institutions that had emerged, were not sufficient for the task at hand. There was an obvious requirement to go further.

The Need for Effective Institutions

What is not explicitly described in Hampson’s definition is this notion of effectiveness. Democratic institutions and procedures must be perceived broadly as effective in order to be so. There is a requirement to internalize the norms of democracy and to embed confidence in the effectiveness of democratic institutions in the hearts and minds of the society being rebuilt. This requirement to change norms is discussed by Peceny and Stanley in their examination of recent Central American peace processes. They describe a four-step process for changing norms, offering a ‘norms cascade’ that leads to internalization of liberal democratic norms, to the point where democracy and action through liberal institutions becomes the habitual route for the resolution of political conflict.19

Specific to El Salvador, Peceny and Stanley describe a process whereby elites began to adopt liberal norms outwardly and publicly through the 1980s in order to legitimate themselves to the international community. This gained them an increasing level of international support and engagement. Through a five-year peacebuilding mission in the country, the UN worked to strengthen liberal political institutions and to promote “dialogue, compromise, and non-violent conflict resolution, successfully diffusing liberal practices to state bureaucracies and ... society.”20 This diffusion of liberal norms worked its way through previously antagonistic groups, gradually shifting conflicts into the political realm that previously would have been resolved through violence. This process was underpinned and fostered by extensive economic development and by the assistance of the international community, most especially the US. The key to this process was having former combatants internalize liberal identities and norms prior to the disengagement of the international community.

The peace that should be sought for Haiti must encompass all the elements previously discussed. It must be a peace marked by a sustained absence of political violence, one that will endure after the departure of the peacebuilders, one that sees a democratic Haitian state with robust institutions, and one where Haitians themselves have adopted the norms suitable for the sustainment and nurturing of a functional democratic state.

Nature of the Current Conflict in Haiti

Having defined the key aspects of the peace that must be built, the article will now turn to a consideration of the nature of the current conflict in Haiti. Perhaps the simplest perspective from which to approach this discussion is first to define what the conflict is not. To begin with, this is not an ethnic conflict. Daniel Byman describes an ethnic group as a people “bound together by a belief of common kinship and group distinctiveness, often reinforced by religion, language, and history.”21 This certainly describes the Haitian people, but it applies to all those who live in the country. There are no cleavages of ethnic identity that lie at the base of the conflict. In a similar vein, much of the literature on civil conflict discusses security dilemmas as a common cause of intra-state violence. While the Haitian people do often fear for their personal security, the security dilemma, as described by Barbara Walter, amongst others, is not active in this case. There is no ‘other’ group to fear.22 Neither is this a conflict that has been sparked by – transition – political, economic, or otherwise. This is not a state that fell apart under the pressures of democratization, or from economic development and modernization.

The main culprits in this conflict are state weakness and a chronic lack of popular legitimacy. The roots of this problem are not recent. They stretch back to the foundation of Haiti as a state, and some consideration of the historical legacy of the country is essential to an understanding of the current situation.

Historical Roots of Conflict

The French colony of Sainte-Dominigue, the precursor to the state of Haiti, was the economic engine of France during the 1700s. Sainte-Dominigue produced vast quantities of commodities for export to metropolitan France, which would then be further processed and resold for vast profits. Sainte-Dominigue was a net importer of food; the mode of production was based upon a system of large plantations, worked by approximately 500,000 primarily African-born slaves under extremely brutal conditions. From the moment of capture, the life expectancy of a slave was estimated to be seven years, and it was assumed to be cheaper to import new slaves from Africa than to breed them domestically.23 There was a small but significant class of black freedmen, and those of mixed race engaged in small commerce, and they were mainly concentrated in urban areas. Sitting atop the social pyramid were the French-born grand-blancs, who owned the majority of the plantations, and who were responsible for the administration of the colony.

Haiti is the only state to have been born as a direct result of a slave uprising. The revolution began in 1792, and lasted 12 years. The struggle was protracted, racially polarized, and extremely brutal. The culminating act was the order by Jean Jacques Dessalines, a revolutionary leader who later proclaimed himself emperor, to kill any white people remaining on the island.24

Subsequent to the revolution, the country was isolated diplomatically and economically, since the United States and the European powers feared that the slave revolution would spread. Diplomatic recognition was very slow in coming, and international trade was severely restricted. The revolution had left the country in ruins, through both the extensive destruction of infrastructure and the destruction of the former economic model. Initial abortive attempts to re-establish the plantation system only demonstrated that the newly-freed slaves were not willing to return to plantation labour. Shortly thereafter, Dessalines divided the estates of the departed French among the freed slaves. This is the crucial act that laid the economic, social, and psychological foundations of modern Haiti.25 The great majority of freed slaves lived in rural areas, farming small plots of land on a subsistence basis, selling their surplus to the towns and cities. Conversely, there developed an increasingly privileged, urban, mixed-race bourgeoisie who made their livings from this economic situation. Trouillot succinctly describes the system that emerged.

Peasant crops and imported consumer goods were the mainstay of local economic exchange. Taxes collected at the customhouses and ultimately borne by the peasantry provided the bulk of government revenues. Profits made from the peasantry contributed a large share to the returns garnered by an import-export bourgeoisie that was dominated by foreign nationals and unconcerned with local production.... While the state turned inward to consolidate its control, the urban elites who gravitated around that state pushed the rural majority into the margins of political life.26

This basic economic model lies at the roots of the present divide existing between the Haitian state and the Haitian nation. The Haitian sense of nation, forged in revolution, and, subsequent isolation, is very strong. Haitians share a common history, religious heritage (Voodoo), and language (Creole). However, the Haitian state itself is weak, and the institutions of governance are not well entrenched. Since 1804, Haiti has been an empire twice, a kingdom once, and a republic numerous times, of which nine republics appointed presidents for life.27 It is not perhaps the magnitude of the political instability that makes the problem of Haiti unique and challenging, but the persistence of political failure. From the outset, there has been an ongoing predatory relationship between the Haitian political elites and the masses. This fact is not lost on the Haitian people, and is quite explicitly laid out in the 1987 constitution. This is the specific relationship that must be severed and then rebuilt. The institutions of Haitian democracy must be extended and strengthened to allow the Haitian people an effective voice in government. However, such an undertaking must go hand-in-hand with extensive economic development and support from the international community that will allow the majority of Haitians to benefit tangibly from these newly strengthened political institutions.

DND Photo HS048069d01 Corporal Matthew McGregor, Formation Imaging Services Halifax

A CH-146 Griffon Helicopter from 430 Squadron flies over the city of Port-au-Prince.

The MINUSTAH Mandate Considered (circa 2005)

The current mandate of MINUSTAH does seek to address some of these requirements. However, it is hampered by underlying assumptions and restrictions, imposed by the reality of the current United Nations system and its approach to peacekeeping operations. As mentioned, the key restriction is found in the preamble to the document, where the UN affirms its “strong commitment to the sovereignty [and] independence” of Haiti.28 MINUSTAH is constrained to operate in support of, and through, existing government structures in Haiti. In essence, this means operating within a culture and structure of governance that produced the current state of affairs in the first place. At a minimum, the actions of the UN are tainted by its association with a government lacking legitimacy in the eyes of many.

This constraint to work with and through current government structures is coupled with a call to hold elections at the earliest possible date. This is the pattern followed by many UN missions in the 1990s: international intervention to provide a safe and secure environment, followed by elections at the earliest opportunity, followed by the fairly rapid withdrawal of international forces. Given the current state of the nation, and the fact that at least one major political party, the Fanmi Lavalas, is refusing to participate in elections scheduled for November 2005, the repetition of the next steps in the pattern are perhaps inevitable: gradual deterioration of the security situation post-election and post-withdrawal, followed by large-scale violence, followed by a call for international intervention.

Elections should not be held before they can be carried out in a sufficiently institutionalized and effective framework. The Haitian people must have had time to internalize the norms that surround these acts. This is a long-term process.

In a similar vein, the mandate calls for MINUSTAH to support the Transitional Government in fostering “principles and democratic governance and institutional development,”29 and assisting with the “restoration and maintenance of the rule of law.”30 All these issues are critical to the development of legitimate and effective governance and long-lasting peace in Haiti, but again, these modifications involve changing norms, and are very long-term undertakings.

To be fair, the MINUSTAH mandate does speak to the longer term, in that it,

[e]mphasizes the need for Member States, the United Nations organs, bodies and agencies and other international organizations .... to continue to contribute to the promotion of social and economic development of Haiti, in particular for the long-term, in order to achieve and sustain stability and combat poverty.31

However, the rolling six-month mandate, the expense of maintaining the mission, and the lack of long-term commitments from member states all work to the detriment of realistic planning to achieve long-term goals. The history of UN engagement in Haiti through the 1990s, with the quick drawdown of the UN presence and the rapid return to instability, suggests that this is not an inconsequential factor.

The Case for Trusteeship

One solution to address these inadequacies is a UN trusteeship for Haiti. The UN should assume governance of the state, with a view to establishing the conditions necessary for the emergence of a democratic culture sufficiently robust to ensure that political rivalries will not turn violent. The broad tasks of the UN administration should largely mirror those outlined in the MINUSTAH mandate, but they should be directly implemented by a permanent, non-rotating UN administration, therefore avoiding the constraints of the existing culture and system of governance. An implicit goal of the United Nations administration should be to change existing norms of governance, building confidence in democratic institutions. The overarching aim should be to build a system of governance that will be instrumental in improving the lives of the Haitian people and that will be seen as legitimate. This is neither a quick nor a cheap solution to the problem, but given the history of the Haitian state, it is required.

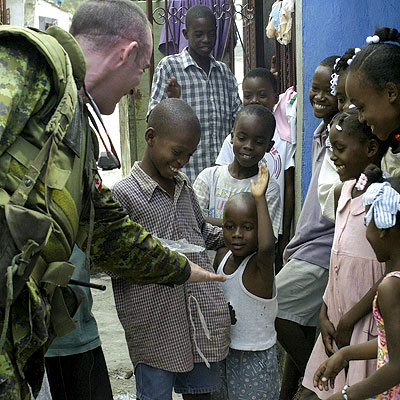

DND Photo HS048019d07 Private Matthew McGregor, Formation Imaging Services Halifax

Canadian Forces Civil-Military Co-operation team member Captain Shawn Courty from Saint John, New Brunswick befriends a young Haitian boy and gets a ‘high five’ from him as a crowd of other young children watch.

Institutionalization before Liberalization

Roland Paris lays out a roadmap for effective trusteeship in his framework for Institutionalization before Liberaliztion (IBL).32 In essence, the argument is that the current widely shared belief that “democratisation and marketization [sic] will foster peace in war-shattered states” while sound, is fraught with the danger of instability and a return to violence during the turbulent period of transition. These dangers must therefore be controlled through a deliberate, incremental and carefully managed introduction of reforms. Further, the sequencing of these reforms is critical, as political and economic institutions capable of managing the strains of democratization and liberalization must be established before a managed liberalization takes place.33

Of the six key elements of Roland Paris’s IBL approach towards building the peace, two offer particularly useful guidelines with respect to a United Nations trusteeship for Haiti. The first addresses the timing of elections. Paris argues that elections must wait until the time is right for them to be held, until conditions are ripe. He holds two criteria for such timeliness – firstly, the principal contenders for the elections must not be those who recently engaged in the civil war, and secondly, the nation’s institutions must be sufficiently up to the task of resolving disputes arising from the election. Measured by either of these criteria, Haiti is not ready, and it is likely that considerable time must pass before the conditions will be ripe.

There is also a requirement to adopt conflict-reducing economic policies. Given Haiti’s historic legacy of poverty and underdevelopment, it would appear that the primary conflict-reducing economic policy should be a massive program of economic and social assistance to the nation. The goal would be to establish a functioning economy that affords some significantly increased measure of economic opportunity in a country where, as previously mentioned, 40 percent of households are faced with food insecurity, and unemployment runs at 50 percent.

Underlying all of the key elements of Paris’s IBL approach is the requirement to rebuild effective state institutions. Paris’s inventory of required institutions looks very much like the checklist in the MINUSTAH mandate. A functioning judicial system and courts, the rule of law, and effective police forces are elements considered in both documents. What is missing from the MINUSTAH document is the appropriate appreciation of the time required to institute these desired end-states.

The logic of the trusteeship solution with respect to the current problems in Haiti is sound, but it rests on one fundamental assumption – that of political will. It assumes that the will of the international community really is as expressed in the goals of the mandate issued for MINUSTAH, and that the international community is prepared to do what it takes to get the job done. If this is not the case, then the argument becomes moot, and we will see a repeated cycle of short-term mandates applied as ‘band-aid fixes’ to get past the crisis of the day.

DND photo HSspeciald04

Haitian National Police and aid workers are transported by CH-146 Griffon helicopters to Mapou, Haiti, during relief flights.

Challenges to Trusteeship

There is little doubt that the trusteeship solution in Haiti comes with a number of challenges. Firstly, it entails a profound violation of state sovereignty. However, the international community is engaged already within the borders of Haiti, and thus already has undertaken to interfere in the sovereign doings of a member state. To undertake a trusteeship is but a small step further, and since it touts the ultimate goal of improving the lot of the nation, the argument advanced here is that it is justifiable.

Then there is the argument of the magnitude of the undertaking in terms of the long-term commitment of manpower and resources. However, as argued by Paris, when compared to the monies spent on defence throughout the world, the sums required to set up an effective United Nations trusteeship, even over a period of 20 or 40 years, is miniscule.

Finally, there is what could perhaps become the Achilles heel of this approach, namely, the requirement to achieve a greatly increased level of state legitimacy in Haiti through an approach originating outside the nation itself. This is an issue that will require considerable attention. The Haitian people obviously will have to assume increasingly the predominant position in the structures of the trusteeship, and also to be given the dominant voice in developing appropriate solutions. The pace and scope of this involvement will have to be carefully managed in such a way that the Haitian people will perceive that a Haitian solution has been developed for the Haitian nation. The trick will be to ensure that the international community has been sufficiently successful in inculcating the norms of peaceful democratic process in the Haitian people before this solution is placed under Haitian control.

Summary and Conclusions

The unique cultural entity that is Haiti presents an enormous challenge to the international community’s efforts at peacebuilding. For the past 200 years, the Haitian state has lacked legitimacy in the eyes of the greater part of the Haitian nation. The European institutions that Haiti inherited from France have never found an easy place in the culture of the Haitian people. For the past 12 years, the United Nations has deployed five separate missions to the island, all of which used a fairly conventional range of techniques to foster a stable and democratic nation there. This approach has not been successful, because it has devoted neither the time nor the resources required to the problem. After ensuring a secure and stable environment, the key task of the international community is to build the institutions of the Haitian state, and to develop, foster, and promote the political space in which the Haitian people can resolve their differences without resorting to violence. It has been argued that the most appropriate avenue for this type of approach is an international trusteeship for Haiti, which demands that the United Nations abandon its current commitment to the sovereignty and independence of the country. Following the logic of Roland Paris, institutionalization must precede liberalization, such that the Haitian nation gains a confidence in the effectiveness of these state institutions, and avoids a return to violence as the primary means to political power.

This is neither a quick nor a cheap undertaking. However, the demands of establishing “a peace that will last beyond the departure of the peacebuilders themselves and into the foreseeable future”34 demands this type of commitment. Whenever the UN interferes in the internal affairs of another nation in the cause of peace, it is de facto imposing its particular set of values and ideals upon that nation. Changing values and ideals is a long process, and one that requires a great commitment of resources and time. If the UN does not acknowledge this fact, and fails to take the time required to do a complete job in Haiti, it will be doomed to return time and again to apply yet another band-aid to the same wound.

DND photo IS2004-2006a by Sergeant Frank Hudec, Canadian Forces Combat Camera

A CC-130 Hercules transport aircraft carrying Canadian citizens, departs Toussaint Louverture Airport in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Two Hercules aircraft flew out 46 Canadians and 17 people of other nationalities on Sunday, 29 February 2004.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Doctor Sarah Meharg of the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre for her much-needed editorial assistance with this article.

![]()

Michael Ward, a tactical helicopter pilot, is currently the Director of Learning Design and Program Support for the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre. He has served in both Somalia and Haiti on peace operations.

Notes

- Three UN Security Council resolutions trace the evolution of UNMIH’s mandate: 867 (1993), 940 (1994), and 975 (1995). The initial mandate under resolution 867 was quite limited (police monitors, military training, and reconstruction teams). However, the initial UNMIH mission deployment was blocked by the Haitian military government. After much diplomatic manoeuvring and tense negotiation, a Multinational Force, authorized under Chapter 7 of the United Nations Charter and led by the United States, deployed to the state to ensure a secure and stable environment. UNMIH was subsequently deployed in 1995.

- UN Security Council, Resolution 1542 (2004), S/RES/1542 (2004), 30 April 2004, p. 4.

- Ibid., p. 1.

- The works of several authors consulted outline the particular division of state and nation in Haiti. Trouillot devotes a considerable amount of time to elaborating upon this theme. He clearly outlines the fact that a combination of political and economic factors dating from the time of the revolution has produced a deep division between the Haitian civil and political society, which reached its peak during the dictatorship of the Duvaliers. Bellegarde-Smith takes this case further by saying that essential and unique aspects of Haitian culture are not reflected in Haitian state institutions, and that this is the key defect that must be rectified before Haitian democracy can take hold. Further, while the Haitian state is very weak, the sense of Haitian nationhood is very strong. The author believes that this distinction is crucial for the formulation of an effective long-term peace-building solution in Haiti (and might in fact lead ultimately to the failure of any internationally imposed peacebuilding effort). Therefore, throughout the article, I will continue the distinction between the Haitian state and the Haitian nation, with the state referring to the institutions of the political entity of Haiti, and the nation referring, necessarily loosely, to the totality of Haitian civil society. Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Haiti: State Against Nation, The Origins and Legacy of Duvalierism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1990), pp. 15-31. Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, Haiti: The Breached Citadel. (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1990).

- Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Report: Haiti, February 2005, (London: The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, 2005), p. 171.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Keeping the Peace in Haiti? An Assessment of the United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti Using Compliance with its Prescribed Mandate as a Barometer for Success, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Law Student Advocates for Human Rights and Centro de Justicia Global, March, 2005), p. 12.

- Economist Intelligence Unit, p. 15.

- Keeping the Peace in Haiti? An Assessment of the United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti Using Compliance with its Prescribed Mandate as a Barometer for Success, p. 10.

- Economist Intelligence Unit, pp. 5-12.

- Amnesty International, Haiti: Breaking the Cycle of Violence: A last chance for Haiti? AMR 36/038/2004, 21 June 2004.

- Stewart Prest, Upheaval in Haiti : The Criminal Threat to Canada, a Background Study, (Ottawa: Carleton University for Criminal Intelligence Service Canada, June 2005), p. 4

- Ibid., p. 26.

- The article will make an assumption that the broader will of the international community is reflected through the actions of the United Nations, and therefore will have as a central focus an analysis of the recent United Nations mandates for Haiti.

- Daniel Byman, Keeping the Peace: Lasting Solutions to Ethnic Conflict (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), p. 6.

- Roland Paris, At War’s End: Building Peace after Civil Conflict (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 59.

- Fen Osler Hampson, “Can Peacebuilding Work?” Cornell International Law Journal, Vol. 30, No. 3, 1997, p. 716.

- The constitution was profoundly liberal and reformist. Perhaps the most important measures were that it decriminalized the Voodoo religion and established Creole as an official language. It divided executive power between a President and Prime Minister, set up an independent council to oversee elections, established an office for citizens’ protection, enshrined civil and political rights, and instituted measures aimed at establishing a more equitable economic order. Social welfare, personal security, and free education at all levels were emphasized.

- Marc Peceny and William Stanley, “Liberal Social Reconstruction and the Resolution of Civil Wars in Central America,” International Organization, Vol. 55, No. 1, Winter 2001, p. 155-157.

- Ibid., pp. 163-164.

- Byman, p. 5.

- Barbara F. Walter, “The Critical Barrier to Civil War Settlement,” International Organization, Vol. 51, No. 3, Summer 1997, p. 516.

- Bellegarde-Smith, pp. 39-40.

- The spirit of the times may be reflected in a quote concerning the drafting of the Haitian declaration of independence, wherein Dessalines’s secretary declared that to the write the act “we need a white man’s skin for parchment, his skull for an inkwell, his blood for ink and a bayonet for a pen.” Ibid., p. 44.

- Greg Chamberlain, South America, Central America and the Caribbean 2005, Jacqueline West (ed), 13th Edition, (London: Europa Publications, 2004), p. 516.

- Trouillot, p. 16.

- Bellegarde-Smith, p. xix.

- UN Security Council, Resolution 1542 (2004), p. 41.

- Ibid., p. 3

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Paris, p. 188.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Ibid., p. 59.