This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

The Peacekeeping Debate

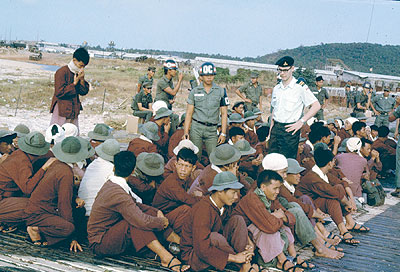

DND photo VNC73-394

Hungarians and Canadians at Quang-Long, Vietnam, while serving on the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), 6 January 1973.

The Peaceable Kingdom? The National Myth of Canadian Peacekeeping and the Cold War

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

With the expansion of Canada’s mission in Afghanistan, the debate over the appropriate role of the Canadian military has been raging. Much of the discussion centres on Canada’s historical tradition of peacekeeping, and what Canadians visualize as legitimate action on the international stage. Many have criticized Canada’s seeming abandonment of the cherished principles of peacekeeping and United Nations (UN)-led multilateral actions. A great amount of this rhetoric reflects the so-called ‘peacekeeping myth,’ the idea that the Canadian Forces (CF) has historically made peacekeeping its primary mission, and that this peacekeeping has been motivated largely by altruism and humanitarianism. Canadian participation in Afghanistan is seemingly incongruous with this pervasive peacekeeping myth. Canadian soldiers are not keeping peace, they are making it. More importantly, Canadians in Afghanistan have fought first under American, then North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) command. This conflicts with the popular Canadian image of the UN blue beret patrolling the ‘green line’ between two enemies. Two of the most prominent proponents of the peacekeeping myth are the academic, A. Walter Dorn, and the journalist, Peter C. Newman. In the Winter 2005-2006 edition of Canadian Military Journal, Dorn argued that Canada was abandoning its historical commitment to impartial, humanitarian United Nations peacekeeping. Likewise, Newman has recently written that Canada participated in Cold War peacekeeping missions in order to pursue being a “peaceable kingdom.”

This article is intended as a refutation of the historical myth of Canadian peacekeeping presented by commentators such as Dorn and Newman. When considering the motivations underpinning Canada’s peacekeeping missions, it is important to place them in context. From 1954 to 1973, the Cold War and the spectre of the Soviet Union were dominant considerations in the formulation of Canadian international policy. Canadian leaders feared Soviet aggression and the spread of communism, and they put their faith in multilateral organizations, such as the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the British Commonwealth, to defend Western interests and to prevent local conflicts from escalating into nuclear war. Peacekeeping was not considered separately from these more pragmatic considerations. In fact, peacekeeping was seen by Canadian planners as complementary to the strategic interests of Canada and NATO.1

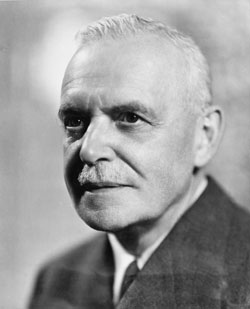

PA photo C-010461

The Right Honourable Louis S. St. Laurent, Prime Minister of Canada 1948-1957.

This article will consider Canada’s operations in Suez, Vietnam, Cyprus, and Afghanistan. The three historical case studies will be used to compare how the espoused reasons behind peacekeeping, and the myth of peacekeeping that surrounded them, stacked up against the ‘real’ motivations. Afghanistan will be relied on primarily to show how historical conceptions of Canada’s military role have shaped contemporary discourse. This article will argue that the Canadian peacekeeping myth promulgated by observers such as Dorn and Newman is false, and that, today, it largely serves to confuse public debate on the appropriate role of the armed forces. Far from being impartial advocates of global harmony, Canadian peacekeepers have been, in fact, Cold Warriors. When engaged in peace operations from 1954 to 1973, Canadian foreign and military policy served the national interest: helping to stop the spread of communism; acting as zealous Western representatives on international bodies; maintaining important geographical areas open for use by the West; and, most prominently, working to maintain unity and cohesion in multilateral organizations important to Western interests, especially NATO.

The Context and the Myth

Canada’s image of itself as a peacekeeping nation has been cemented into the national consciousness. In the popular imagination, Canadian soldiers do not fight wars, they fight war itself. According to John Holmes, a former Canadian diplomat and scholar, peacekeeping was seen as a duty appropriate for an emerging ‘middle power’, especially one so apparently devoted to world peace.2 Peacekeeping also served to differentiate Canadians from Americans. In the words of J.L. Granatstein: “Canadians were middlemen, honest brokers, helpful fixers in a world where these qualities were rare. Peacekeeping made us different and somehow better.”3

Canadians have not always understood their armed forces in these terms. During the Second World War, Canadians thought of their soldiers as warriors, on the side of good of course, but in a time when good meant fighting wars. Canada was also generally more isolationistic in its foreign policy at the time. After the Second World War, however, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was replaced by a new group of Liberals much more eager to participate in world affairs. The root of this new orientation can be found in then–Secretary of State for External Affairs Louis St. Laurent’s 1947 speech, ‘The Foundation of Canadian Policy in World Affairs’, in which he argued that a pillar of Canadian foreign policy should be the “acceptance of international responsibility in keeping with our conception of our role in world affairs.”4 In practical terms, this meant that Canada would be far more eager to become involved in international organizations and obligations. The rationale for this decision also can be found in the lecture. In the nuclear age, Canada was no longer a ‘fire-proof house.’ According to St. Laurent: “We have realized also that regionalism of any kind would not provide the answer to the problems of world security.”5 In the post-war world, it was believed the best way to guarantee Canada’s security would be multilateralism.

So far, this account of Canada’s foreign policy is entirely consistent with the peacekeeping myth. According to that myth, Canada became more international in its outlook in the interests of peace. Canadian leaders saw the United Nations as the ultimate mechanism by which to defuse superpower conflict. While this certainly is partially true, much of what Canadian planners saw as multilateralism was understood in the context of their membership in the Western power bloc during the Cold War, Canada most definitely was not a neutral arbiter. The Soviet Union was seen as a dangerous threat, and NATO was the essential organ for Western collective security.

In 1956, during an address to the House of Commons, the then–Secretary of State for External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson, provided a pessimistic analysis of Soviet intentions on the world stage. According to Pearson, the USSR had three long-term international objectives. The first “fundamental objective of Soviet policy...is security for the Soviet Union and the triumph of communist ideology in a world of communist states controlled and dominated by Moscow.”6 The second objective was “to win over, subvert, and eventually engulf the uncommitted millions in Asia and Africa,” while the final goal was “to weaken, divide, and eventually destroy the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and drive the United States out of Europe.”7 Pearson’s predecessor as Prime Minister, John Diefenbaker, held a similar view of Soviet intentions. In the House of Commons in December 1957, Diefenbaker argued that “the aim of the Soviet bloc is to weaken and disrupt the free world. Its instruments are military, political and economic, and its activities are worldwide.”8

In the mind of Canadian leaders, the Soviet Union was therefore a dangerous expansionist power whose ideology and tactics threatened the viability of the ‘free world.’ The best hope for Canadian security therefore lay in NATO. According to Pearson, the supposedly unflinching partisan of the United Nations, “as long as [the UN] remains an imperfect standard for peace...NATO is essential as a deterrent and a shield against aggression.”9 The 1964 White Paper on Defence reinforced ideas concerning the dangers of Soviet expansionism. According to Paul Hellyer, then-Minister of National Defence: “The communist countries can be expected to continue to promote expansionist aims by measures short of all out war. Tensions will persist. In the North Atlantic area there will, therefore, remain a corresponding need to maintain intact the military and political cohesion of NATO.”10

PA photo C-094168

Mr. And Mrs. Lester B. Pearson, on the occasion of the Prime Minister receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, 1957, Oslo, Norway.

Hellyer also explicitly discussed the role of peacekeeping in Canadian foreign policy. According to the White Paper, due to communist pressure in the developing world, “instability will probably continue in the decade ahead and call for containment measures which do not lend themselves to Great Power or Alliance action. The Peacekeeping responsibilities devolving upon the United Nations can be expected to grow correspondingly.”11 In other words, NATO was the most important body for Canadian defence, while peacekeeping was useful in terms of anti-communism and the maintenance of international stability.

Despite this attitude, the Canadian government was not a passive observer regarding the myth of peacekeeping; rather, it aided in its active construction. According to Secretary of State for External Affairs Paul Martin Sr. in 1964: “Canadians have demonstrated by their support of peacekeeping actions in...Vietnam, Yemen, the UN Emergency Force in Gaza, in the Congo, and now in Cyprus, their conviction that the United Nations must not fail in its vital peacekeeping function and their determination that Canada shall play its full part in these endeavours.”12 Furthermore, he added, “peacekeeping has been pre-eminently the province of the middle and smaller power,”13 a role in which “UN peacekeeping forces [have] been essentially impartial.”14 Peacekeeping to Paul Martin was “the most revolutionary development yet to occur in the field of international organization,” a concept in which “Canada has played an acknowledged part.”15

Sean Maloney has written about the Canadian peacekeeping myth, something he closely identifies with “Canadian exceptionalism,” which holds that Canada is different and morally superior to the United States.16 According to this idea, Canada is non-violent and non-military. It was quasi-neutral in the Cold War and acted to restrain the superpowers. Canada has no economic ambitions outside of North America, and Canadians are nice and altruistic, unlike Americans.17 Therefore, on the international stage, Canada has been involved predominantly in peacekeeping and humanitarianism.18 The peacekeeping myth is very important in colouring how Canadians view their involvement in Cold War peace operations, and it is still alive and well today.

The debate over Afghanistan is rife with examples of how the myth of peacekeeping still forms the dominant public discourse regarding the Canadian military abroad. One of the biggest critics of Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan is A. Walter Dorn, a professor at the Canadian Forces College. Dorn not only argues that Canada has abandoned true peacekeeping, but that Canada’s past peacekeeping was motivated by altruism. According to Dorn: “Peacekeeping is not war by other means. Peacekeeping does not exist to fulfill narrow-minded national interests, but to help the afflicted population in war-torn areas create the conditions for a sustainable peace and a normal lifestyle.”19 Furthermore, Dorn claims that “a legitimate UN mandate, consent for deployment, impartiality and the minimum use of force are time-honoured standards.”20

Dorn appeals to the mythic idea of a lost peacekeeping past, where Canada fought valiantly for world peace, blind to its own interests. Other commentators have followed suit, Peter C. Newman being a prominent example. Curiously enough, he acknowledges the existence of the myth. Newman states that while altruism and humanitarianism do not direct contemporary policy, they did so in the past. He says that Canadians were “justifiably proud of our role as a neutral third party that kept traditional enemies from shooting at each other.”21 Indeed, Newman argues that “throughout our relatively brief and decidedly un-bloody history, we have stubbornly pursued this quest for a peaceable kingdom.”22

Elements of the peacekeeping myth colour not only the statements of academics and journalists, but those of our leadership as well. Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s March 2006 speech to Canadian troops in Afghanistan in March was a well-publicized event. Parts of the speech contradict the peacekeeping myth. Harper acknowledged that Canadian participation in Afghanistan was contingent on Canada’s national interests, especially in regards to anti-terrorism.23 However, much of the speech plays off public perceptions of the peacekeeping or altruistic tradition. Harper argues that Canada’s national interest is to “see Afghanistan become a free, democratic, and peaceful country.”24 However, he asserts that the work of Canadian soldiers “is about more than just defending Canada’s interests.” It also includes “demonstrating an international leadership role” and performing “great humanitarian work.”25 According to Andrew Coyne, a journalist for the National Post, Harper was not “suggesting Canadians should ask what they can do for their country, but rather what they can do for the world.”26 Indeed, Harper appeals to popular notions of Canadian exceptionalism: “implicit in Mr. Harper’s address is a very different sort of nationalism: a nationalism of moral purpose. Canada exists to do good, for its own people and for the world.”27 This is a truly succinct statement of the myth of peacekeeping.

The peacekeeping myth dominates discussions of Canada’s post-war military past, and continues to confuse debates over Canada’s military future. However, the peacekeeping myth, in claiming that Canada was motivated to keep the peace primarily by altruism and moral virtue, is false and misleading. Dorn and Newman provide two particularly egregious examples of this error. As the following examples demonstrate, the true reasons behind Canadian involvement in Cold War peacekeeping stemmed, in fact, from pragmatic Cold War strategic interests. Despite the popular conception of peacekeeping cherished by the Canadian public, peacekeeping missions served to advance Canada’s national agenda in a Cold War world.

DND photo ME-135 by Hunt

Mine clearing in New Suez, 28 November 1956.

United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF)

The crisis over the Suez Canal remains the most enduring symbol of Canada-as-peacekeeper. While UNEF was not the first example of UN peace operations, Suez nonetheless was an important event that threatened the viability of the nascent UN and NATO. Canadian leaders in 1956 claimed that by conducting peacekeeping, they were motivated by humanitarian concerns and a desire to contain the conflict. While this may be partially true, Canada’s actions in Suez were primarily driven by a need to prevent key multilateral organizations from fracturing, notably the Commonwealth and NATO.

The spark which eventually resulted in the Suez crisis was the nationalization of the Suez Canal by Egypt from its owner Britain in June 1956. Losing control over the canal threatened the strategic interests of the European powers, as the canal provided a fast sea link to Asia and an easy conduit for Middle Eastern oil.28 When the Israeli army invaded Egypt on 29 October, France and Britain issued an ultimatum, saying that police action was necessary to maintain peace between Israel and Egypt.29 On 31 October, Louis St. Laurent refused to join the British after a call for allied aid.30 After abstaining from a vote in the General Assembly condemning the British and the French, Pearson rose to call for the creation of a UN police force large enough to maintain peace while a diplomatic solution could be worked out.31 Pearson was in an awkward position between the nation’s greatest allies. The Americans condemned the actions of the British and the French, thinking invasion would only cause more problems.32 However, Pearson felt uncomfortable condemning Britain outright.33 A UN peacekeeping force presented a solution to the problem, and the UNEF was formed. Canada initially sent a transport squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force and 300 administrative personnel, increasing its troop commitment to over 1000 by 1957, comprising more than one-sixth of the entire UNEF force.34

DND Photo ME-409 by Jolley

Time for sightseeing... Three members of Canada’s UNEF Contingent in Egypt watch traffic on the Cairo-Ismalia Canal on 18 February 1957.

When justifying Canada’s involvement in Suez, our leaders tended to emphasize the humanitarian concerns at stake, a motive consistent with the myth of peacekeeping. In his statement to the United Nations on 2 November 1956, Pearson described the situation on the ground as “of special and, indeed, poignant urgency, a human urgency.”35 He called for the creation of UNEF on the basis of humanitarianism, saying that “we have a duty here” to bring “some real peace and a decent existence, or hope for such, to the people of that part of the world.”36 In the Speech from the Throne on 26 November 1956, Louis St. Laurent reinforced the public profile of the altruistic reasons drawing Canada into peacekeeping, reminding the House that the nations of the world signed the UN charter “to use peaceful means to settle possible disputes and not to resort to the use of force.”37

Therefore, according to official statements from the Canadian government, Canada was involved in the Suez in the interests of peace, and to protect humanitarian concerns in the area. However, most historians disagree with the peacekeeping myth as applied to Suez. The general consensus regarding Canadian involvement in UNEF was that it was motivated by a desire to prevent disunity and fracture within NATO and the Commonwealth, as the well as to ‘save’ the British and French from a dangerous blunder. The British and French invasion of Egypt put a great amount of pressure on NATO and the Commonwealth, two multilateral organizations that Canada considered important to its interests. Firstly, the United States was deeply opposed to the invasion, going so far as to cut off contact with the British and to draft a resolution condemning their actions.38 This threat-ened the British-American strategic relationship that Canada saw as so valuable. In the days of the crisis, Canada acted as a go-between, what Granatstein calls the “hoary cliché” of the lynch pin.39 In discussing the motivations behind Suez, John Holmes identifies “sav[ing] the Anglo-American entente” as paramount.40

British actions not only threatened the unity of NATO, but the Commonwealth as well, which included India, Pakistan, and Ceylon.41 Fresh from their own decolonization movements, leaders of these Commonwealth nations were horrified by British actions, leading to calls for complete withdrawal from the Commonwealth.42 It was believed their exit would not only damage the organization itself, but it would leave these countries far more open to Soviet intervention. Thus, an excuse had to be found for the British and French to leave the Canal Zone. UNEF was the mechanism by which this was made possible. According to John Holmes: “There was the strong feeling that the British, aided by the French, had made a ghastly mistake from which they should be rescued.”43

Primary evidence supports the assertion that Canada was motivated by its interests in keeping together NATO and the Commonwealth. In a telegram to British Prime Minister Anthony Eden on 1 November 1956, St. Laurent made no mention of the human tragedy of the invasion, but rather, of three political consequences that troubled him. The first was “the effect of the decisions taken on the United Nations.”44 Greater worries were embodied in the danger “of a serious division within the Commonwealth in regard to your action, which will prejudice the unity of our association,” and finally, “the deplorable divergence of viewpoint and policy between the United Kingdom and the United States in regard to the decisions that have been taken,”45 which could threaten NATO cooperation. As was offered previously, Canada deeply valued the NATO alliance in a world threatened by expansionary communism. Peacekeeping in Suez was one way in which the unity of NATO and the Commonwealth could be maintained.

DND photo CR-338 3 by E. Charles

On 3 April 1958, three “50” guns on HMCS Crescent were turned into a merry go round for the afternoon as 150 Vietnamese orphans visited the ship. Chief Petty Officer Dave Greaves is there to see none of the children fall off the mounting.

International Commission on Supervision and Control (ICSC)

Canada’s involvement in Vietnam from 1954 to 1973 was, in many ways, the opposite of the UNEF experience. Unlike Suez, very few Canadians are even aware of Canada’s commitment of almost 20 years to two peace-supervisory organizations. Secondly, the Canadian operation in Vietnam was not military in nature. Finally, Vietnam was not carried out under UN auspices. Nevertheless, Canada’s participation on the International Commission on Supervision and Control (ICSC, but International Control Commission or ICC for short) emphasizes the pragmatism behind Canada’s participation in international peace operations. As part of the ICSC, Canada acted as a strong representative of the Western power bloc in the context of the global struggle against communism.

In 1954, the decolonization struggle in French Indochina paused for a peace conference in Geneva.46 Vietnamese communists based in North Vietnam (the Viet Minh) had been waging an increasingly bloody conflict against French troops, who were losing control of the area. Provisions were made for the creation of three International Control Commissions, one in each of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, to supervise the truce, and to monitor the free movement of refugees and the release of prisoners of war.47 The Geneva settlement also included a temporary division at the 17th Parallel of Latitude, an agreement to hold elections across Vietnam in 1956, and restrictions on both sides on the importation of outside arms.48 Each ICC was to have a ‘troika’ formation, with a representative each from the Soviet and Western blocs, combined with a neutral representative.49 Canada was asked to represent the West, along with Poland (communist) and India (neutral).50 Canada was initially reluctant to join, especially in light of the lukewarm American response to the Geneva accord. Canada had no experience in Indochina, its armed forces were committed to NATO, and the UN was not involved.51 Nevertheless, Canada agreed to participate after international pressure was levied. According to John Holmes, a “...refusal to play its part would be badly received everywhere.”52

The ICSC had no powers of enforcement; its tasks were to supervise and monitor the truce and the flow of refugees, as well as to look for violations of the Geneva accord. This was initially successful, but the mission soon ran into problems. Restricting the flow of arms into the South and the North soon proved impossible, and by 1957, the ceasefire had disintegrated.53 Furthermore, Canada was continually frustrated by the voting behaviour of the Poles, whose partisanship in favour of the communist North may have led Canada to abandon impartiality in favour of a partisan position.54 With the American escalation of the war in 1964, the ICSC had proven ineffectual. Near the end of the conflict, in 1973, Canada, with Indonesia, Hungary, and Poland, joined a new body, the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), which supervised the ceasefire that allowed American troops to withdraw from Vietnam.55

With respect to its participation in Vietnam, Canadian actions were influenced and informed by a Cold War context that understood communist expansion as a clear threat to Western interests. During the early Cold War era, Western military doctrine held that the nuclear deterrent and troop build-up in Europe would largely dissuade direct superpower conflict. Consequently, Soviet imperialism would be directed against peripheral targets, primarily in Asia and Africa, where the USSR would attempt to gain a strategic advantage over the West. According to the ‘Domino Theory’, the loss of one country to communism would drag its neighbours down into communism as well. Canada, like the United States, sought to prevent the spread of communism into South Vietnam, and Canada hoped to aid the American cause by allowing arms into South Vietnam, acting as a messenger to Hanoi, and spying in North Vietnam.

However, certain public statements of Canadian leaders certainly did not present Canadian actions in this context. The official motivations for Canada’s involvement with the ICC were the maintenance of peace and humanitarianism. When accepting a seat on the ICC on 28 July 1954, the Canadian Department of External Affairs offered the following rationale: “Just as local conflicts can become general war, so conditions of security and stability in any part of the world serve the cause of peace everywhere. If, therefore, Canada can assist in establishing such security and stability in South-East Asia, we will be serving our own country, as well as the cause of peace.”56 This public rhetoric of peaceful intentions continued well into the Canadian mandate.

In February 1965, Paul Martin Sr. supported Canada’s continued presence in terms of the myth, arguing that, “Canada has no national interest to assert in that part of the world. But we do have an interest, as a responsible member of the world community, in helping to ensure that all people in the area are enabled to live under conditions of their own choosing.”57 Both statements illustrate the peacekeeping myth and they portray Canada as a disinterested player that was leading the way to peace by virtue of its intrinsic altruism and moral superiority. To some degree, these statements did reflect Canada’s true motives. Canada, along with the West, did want peace and stability, and peacekeeping was a means by which this could be achieved. However, Canadian actions in Vietnam tell a more complex story, one of a country brought into the ICC as “the West’s champion.”58

The initial guidelines given to the first Canadian ICC commissioner, Sherwood Lett, provide some evidence of Canadian intentions. His letter of instructions states clearly that the Canadians saw the ICC as a way of preventing Laos and Cambodia from falling under communist control.59 Canadian objectives were described as the maintenance of peace, the creation of a regional South-East Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO), and economic and social strengthening of the region’s countries, with the aim of creating strong and independent Western-aligned regimes that could resist communist subversion.60 Two of these three goals were clearly anti-communist.

DND photo PCN73-334

The ICCS at work, Vietnam, 28 May 1973.

Canada acted to further American interests from its position on the ICC. In 1964, Blair Seaborn, the Canadian commissioner in Vietnam, acted as a messenger for the United States to Hanoi.61 Seaborn carried both a ‘stick and a carrot,’ offering the Viet Minh a choice between American escalation and aid to their regime in exchange for an end to militancy against South Vietnam.62 Canadian diplomats also participated in espionage against North Vietnam,63 and intelligence material gathered was passed on to the CIA. As the conflict intensified in the mid-1960s, Canada turned a blind eye towards American arms imports into South Vietnam.64 In 1962, Howard Green, the Secretary of State for External Affairs under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, recognized that both sides of the conflict were receiving arms in contravention of the Geneva accord. However, this was acceptable to him, as, “North Vietnam has engaged...in subversive activities of an aggressive nature directed against South Vietnam....The increased military aid which South Vietnam has received since Dec. 1961 was requested for the purposed of dealing more effectively with these subversive activities.”65 Two years later, Paul Martin Sr. stated that the United States, “...seeks no selfish advantage in Vietnam...only the consolidation of a government free from outside attack and at liberty to determine its own future.”66 These statements clearly added legitimacy to American policy in Vietnam, bol-stering support for its Cold War struggle.

When Pierre Trudeau came to power in Canada in 1968, he employed a new rhetoric of inde-pendence from American foreign policy. Ironically, Trudeau’s willingness to participate in the 1973 ICCS was a direct continuation of his predecessors’ policies, which aided the Americans. By 1972, the Americans were totally stalemated in Vietnam, and they were looking for a way out. President Richard Nixon wanted a withdrawal that would save face, that is, “peace with honour.”67 The ICCS was constituted to supervise a ceasefire as the Americans withdrew, and it lent legitimacy to this withdrawal by providing the image that the war was over.68 Trudeau initially was loath to participate, but he agreed to do so after an American request.69 Although the Canadian commitment lasted only a few months, it was useful in that it helped stabilize the region during the American retreat. Canada left a few months later, in July 1973, their final act in the region as part of the Western bloc complete.

DND photo ISC76-220 by Smith

A Canadian Lynx moves past an observation post in the UNFICYP patrol area during February 1976.

United Nations Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP)

The UN mission in Cyprus provides another example of Canadian motives concerning peacekeeping. While Cyprus became Canada’s longest UN peacekeeping mission, lasting from 1964 until 1993, this article is only concerned with the genesis of the mission, as this most clearly demonstrates why Canada became involved in the first place. Once again, Canada was motivated by strategic reasons derived from its Cold War alignment. Participation in UNFICYP served one major purpose – to prevent tensions between alliance members Greece and Turkey from exploding into war – one that would fracture NATO and jeopardize its strategic position in the Eastern Mediterranean.70

By the 1950s, 80 percent of Cyprus was ethnic Greek, with a sizeable 18 percent minority of ethnic Turks.71 Greek nationalists agitated for enosis, or unification with Greece. This conflict with the British imperial authority culminated in a series of peace talks in 1959. In exchange for independence, Cyprus agreed to allow British Sovereign Base Areas (SBAs), and guaranteed that neither enosis nor an ethnic partition of the island would occur.72 Cyprus gained independence in August 1960, appointing a Greek president and a Turkish vice-president. After Greek attempts to alter the constitution, severe fighting broke out during the Christmas period in 1963. Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios requested British assistance, and both Greece and Turkey threatened to intervene.73

In order to avert a war between Turkey and Greece, Paul Martin Sr. worked to put together a peacekeeping operation. On 11 March, Turkey threatened to land troops on the island to protect Turkish Cypriots, while Greece vowed to retaliate if this occurred.74 Under pressure in Parliament, Prime Minister Pearson said that he had to be convinced that Canadian troops would contribute to peace and stability, and that Canada would not face an indefinite deployment.75 After Lyndon Johnson asked for Canadian troops to participate, Martin managed to get a commitment from Sweden and his own Parliament, and the peacekeeping force landed on 15 March, preventing a Turkish invasion by doing so.76 By April, Canada had committed 1150 members of the total peacekeeping force of 6500 personnel.77 UNFICYP troops were mainly involved in resolving local conflicts and deterring disputes, but Canadian troops in the capital, Nicosia, participated in interpositionary peacekeeping, patrolling the ‘green line’ that separated the combatants.78

The situation in Cyprus was important to Canada because of the strategic situation at the time. The SBAs belonging to Great Britain were used as base sites for both conventional and nuclear weapons. From these bases, nuclear strikes could be launched against the western USSR without having to pass over other Eastern bloc countries, while conventional forces could be deployed throughout the Middle East.79 More importantly, Greece and Turkey were both NATO allies,80 especially Turkey, serving as a base for vital military and intelligence posts. A war between these two nations, it was feared, would undermine NATO’s position in the Eastern Mediterranean.81 Surprisingly, some of Canada’s official reasons for intervening in Cyprus closely match the ‘real’ reasons. In a speech given in May 1964, Paul Martin explained Canada’s position on Cyprus. One theme of his speech closely matched the peacekeeping myth that was traditionally apparent in Canadian statements. The Canadian objective was “...the restoration of order and tranquillity in that island and the maintenance of international peace.”82 Martin portrayed Canada as a great humanitarian nation as well; the “...suffering of the people of Cyprus...demanded the attention of all who believe in human decency and dignity.”83 However, Martin admitted that Canada had strategic reasons in mind as well, as “participation in NATO obligates us to do our utmost to prevent conflict between Greece and Turkey and exposure of the Eastern flank of our alliance.”84

Canada’s actions in Cyprus provide a clear example for the primary motivations behind Canadian peacekeeping during the Cold War. NATO and the strategic interests of the West were threatened by a potential conflict between Greece and Turkey over the island of Cyprus. Peacekeeping thus acted as a mechanism to prevent this conflict, and to maintain the unity of Canada’s most valuable multilateral organization.

DND photo CR-328E by Charles

Part of a group of 150 orphans from Saigon orphanage on the quarter deck of HMCS Crescent, 3 April 1958.

Conclusion

During the Cold War, Canada was deeply involved in several international peacekeeping missions, three of which have been described in this article. Despite popular perceptions of a Canadian tradition of disinterested altruism, Canada’s participation in peacekeeping during the Cold War was primarily motivated by its own strategic interests. Canadians were dedicated Cold Warriors, and perceived the Soviet Union to be a dangerous, expansionary force that threatened the interests of the West. Accordingly, NATO and other multilateral organizations were crucial bodies for the protection of Western interests. In its participation in the UNEF at Suez, Canadians provided a way for the British and the French to extricate themselves from a dangerous blunder they had committed. UNEF also functioned to maintain unity in the British Commonwealth, and it eased tensions between Britain and the United States, two crucial NATO partners. In Vietnam, Canada participated on the ICC as a zealous partisan of the West. Through its rulings on the ICC, Canada aided American efforts to smuggle arms into South Vietnam. In addition, Canadian diplomats working for the ICC acted as messengers between Washington and Hanoi, and provided intelligence on North Vietnam to the Americans. Canadian participation on the second ICC in 1973 served to facilitate the American withdrawal. In Cyprus in 1964, tensions between ethnic Greeks and Turks threatened war between Greece and Turkey. Both were NATO allies, and Cyprus constituted a strategic geographical area for NATO. The Canadian-led peacekeeping mission helped defuse tensions, and it helped prevent a costly split in the NATO alliance.

From these examples, it is clear that Canadian peacekeeping was not principally Canadian altruism exported abroad as many have claimed. Nevertheless, the peacekeeping myth continues to inform debate on Canada’s armed forces today. In this writer’s view, commentators like A. Walter Dorn and Peter C. Newman cling to a false view of the past in arguing that Canada has abandoned its cherished principles by participating in the Afghanistan operation. They argue that Canada had, in the past, pursued being a “peaceable kingdom,” and the nation should return to this ideal. However, historical evidence suggests a much greater continuity between peace operations today and those in the past. Canada is in Afghanistan because our leaders perceive it to be in the interests of Canada. Similarly, Canada participated in Cold War peacekeeping mainly because it believed that it served Canadian and Western interests. Constant reliance on a mythic and idealized form of peace-keeping only serves to cloud and confuse discussion of the appropriate role of Canada’s armed forces abroad. Mythologized, altruistic peacekeeping is largely regarded as ‘good,’ while anything else is automatically ‘bad.’ Canadians must discard this automatic rejection of any military action that does not conform to popular views of traditional peacekeeping. Only then will Canadians be prepared to accept a multitude of roles for their armed forces overseas that can serve Canadian interests properly.

![]()

Eric Wagner is a postgraduate student in History at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

Notes

- Sean M. Maloney, Canada and UN Peacekeeping: Cold War by Other Means, 1945-1970, (St. Catherines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing, 2002), p. xii.

- J.L. Granatstein, “Canada and Peacekeeping: Image and Reality,” in Canadian Foreign Policy: Historical Readings, J.L. Granatstein (ed.) (Toronto: Copp Clark Pitman Ltd., 1993), p. 276.

- Ibid., p. 277.

- Louis St. Laurent, “The Foundation of Canadian Policy in World Affairs,” in Canadian Foreign Policy: Historical Readings, J.L. Granatstein (ed.), (Toronto: Copp Clark Pitman Ltd., 1993), p. 31.

- Ibid., p. 34.

- Lester Pearson, “House of Commons, Jan. 31, 1956,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956 – Selected Speeches and Documents, Arthur E. Blanchette (ed.) (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1977), p. 116.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- John Diefenbaker, “House of Commons, Dec. 21, 1957,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 124.

- Lester Pearson, “Speech to the American Council on NATO, Jan. 29, 1957,” in Ibid., p. 119.

- Paul Hellyer and Lucien Cardin, White Paper on Defence (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1964), p. 11.

- Ibid.

- Paul Martin “Statement to Ottawa branch of the United Nations Association, May 4, 1964,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 44.

- Paul Martin, “Statement to McGill Conference on World Affairs, Nov. 21, 1964,” in Ibid., p. 48.

- Ibid., p. 47.

- Ibid., 46.

- Maloney, p. 2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- A. Walter Dorn, “Peacekeeping Then, Now and Always,” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 6, No. 4, Winter 2005, p. 105.

- Ibid.

- Peter C. Newman, “Canada: Peaceable Kingdom no More,” in Maclean’s Magazine Online Edition, 15 March 2006, at <http://www.macleans.ca/topstories/canada/article.jsp? content=20060320_ 123546_123546>, accessed 4 July 2006.

- Ibid.

- Stephen Harper, “Staying the Course in Kandahar,” in Ottawa Citizen, 14 March 2006, p. A13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Andrew Coyne, “Harper’s Mission Statement,” in National Post Online, 15 March 2006, at <http://www.canada.com/nationalpost/columnists/ story.html?id=cfcd1793-0075-4ff3-8ad0-24ebd55a6d9e>, accessed 4 July 2006.

- Ibid.

- Robert R. Bowie, Suez 1956 (London: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 47.

- The Israeli invasion and subsequent condemnation were the result of collusion between Israel, Britain, and France in an attempt to regain control of the canal.

- John Holmes, The Shaping of Peace: Canada and the Search for World Order 1943-1957, Vol. 2, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), p. 358.

- Lester Pearson,” Statement to UN General Assembly, Nov. 2, 1956,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 12.

- Michael G. Fry, “Canada, the North Atlantic Triangle and the United Nations,” in Suez 1956: Its Crisis and its Consequences, W.M. Roger Louis and Roger Owen (eds.), (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 61.

- Holmes, p. 357.

- J.L. Granatstein and David Bercuson. War and Peacekeeping: from South Africa to the Gulf-Canada’s Limited Wars (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1991), p. 197.

- Lester B.Pearson, “Statement to UN General Assembly Nov. 2, 1956,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- Louis St. Laurent, “House of Commons, Nov. 26, 1956,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 23.

- Holmes, pp. 358-359.

- Granatstein. “Canada and Peacekeeping: Image and Reality,” p. 278.

- Holmes, p. 185.

- Peter Lyon, “The Commonwealth and the Suez Crisis.”, in Suez 1956: Its Crisis and its Consequences, p. 258.

- Ibid.

- Holmes, p. 357.

- Louis St. Laurent, “Telegram to Anthony Eden Nov. 1, 1956,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 14.

- Ibid.

- Granatstein and Bercuson, p. 201.

- Ibid.

- Victor Levant, Quiet Complicity: Canadian Involvement in the Vietnam War (Toronto: Between the Lines Publishing, 1986), p. 111.

- Holmes, p. 205.

- Howard Coombs with Richard Goette, “Supporting the Pax Americana: Canada’s Military and the Cold War,” in The Canadian Way of War: Serving the National Interest, Bernd Horn, (ed.), (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2006).

- Holmes, p. 206

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 217.

- John Holmes, “Canada and the Vietnam War,” in Canadian Foreign Policy: Historical Readings, J.L. Granatstein (ed.) (Toronto: Copp Clark Pitman Ltd., 1993), p. 243.

- Granatstein and Hillmer, p. 299.

- Douglas Ross, In the Interests of Peace: Canada and Vietnam 1954-1973 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), p. 89.

- Paul Martin, “Statement to Board of Evangelism and Social Service of the United Church,” 18 February 1965, in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 316.

- Maloney, p. 48.

- Holmes, p. 209.

- Ibid., p. 210.

- Granatstein and Hillmer, p. 272.

- Levant, p. 178.

- Granatstein and Bercuson, p. 205.

- Ibid.

- Howard Green. “The International Supervisory Commission for Vietnam June 2, 1962,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 311.

- Paul Martin. “Statement to the Standing Committee of External Affairs and Defence,” 9 July 1964, in Ibid., p. 313.

- Levant, p. 214.

- Granatstein and Bercuson, p. 207.

- Granatstein and Hillmer, p. 279.

- Coombs with Goette.

- Maloney, p. 188.

- Ibid., p. 190.

- Ibid., p. 198.

- Granatstein and Bercuson, p. 223.

- Maloney, p. 204.

- Granatstein and Bercuson, p. 223.

- Ibid.

- Maloney, p. 207.

- Ibid., p. 191.

- Granatstein and Bercuson, p. 223.

- Maloney, p. 188.

- Paul Martin, “Statement to Ottawa Branch of the United Nations Association, May 4, 1964,” in Canadian Foreign Policy 1955-1956, p. 43.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.