This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

History

CWM 20020045-425

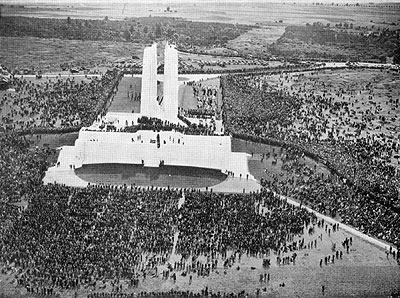

Unveiling Vimy Ridge Monument by Georges Bertin Scott.

“Not a man fell out and the party marched into Arras singing”: The Royal Guard at the Unveiling of the Vimy Memorial, 19361

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

In July 1936, an armed Canadian military contingent returned to France for the first time since the end of the First World War. There was quite a lesser number of Canadians this time around. After all, it was not combat, but the commemoration of previous sacrifices that brought the Canadians to Europe again.

The occasion was the unveiling of the Vimy Memorial on Hill 145, west of the village of Petit Vimy, and the associated pilgrimage to Vimy organized by the Canadian Legion involving more than 6000 “pilgrims.” Years in design, and many more in construction, the memorial signified the sacrifices made by Canadians during the First World War. The inscription on the base of the memorial reads: “To the valour of their countrymen in the Great War and in memory of their sixty thousand dead this monument is raised by the people of Canada.”2 The pilgrims were joined for the unveiling by Canadian veterans living in the United Kingdom, Canadian government officials, various British officials, and a Canadian military contingent. At the actual unveiling, the crowd was estimated to be about 100,000 people, with French military representation and the nearby French population having come out in huge numbers to honour the Canadian sacrifice.3 Pierre Berton would later describe the Vimy Pilgrimage as “the most remarkable peacetime outpouring of national fervour the country had yet seen.”4

The National Representatives

The main Canadian military contingent involved in the Vimy pilgrimage incorporated two parts; two parts, by the way, which would still be familiar to anyone organizing, participating in, or witnessing more recent pilgrimages to battlefields in Europe or elsewhere involving the Canadian Forces. The Canadian military sent a Royal Guard of Honour and musicians to France for the 1936 ceremony. Of particular interest to this article is the Royal Guard that, in an example of common sense and practicality, was composed entirely of members of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN).

For the first time in its short history, the RCN was tasked with mounting a Royal Guard for a reigning British monarch. Not only was the navy to provide the guard, it was also to be formed by the members of a single warship’s crew. The vessel chosen, the destroyer HMCS Saguenay, had been commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy in May 1931, the first warship built to Canadian standards. The Naval Historical Section would later emphasize the significance of the decision:

...here was something more than a ship; here was a symbol – a symbol of Canada’s faith that her future was inexorably bound to her sea-borne trade – of a maturing nation’s acceptance of responsibilities commensurate with her development as a world power – of a people’s belief that peace and prosperity were rooted firmly in pre-paredness and the ability to defend, if necessary, her ocean seaways.5

DHH 81/520/8000, box 222D, file 10

HMCS Saguenay entering Wilhemstad, Cinacoa, Dutch West Indies, 1934.

HMCS Saguenay to the Forefront

In specific terms, Saguenay was tasked with escorting the pilgrims from Canada to France, then forming the Royal Guard for His Majesty King Edward VIII in late July for the official unveiling of the Vimy Memorial.6 HMC ships Saguenay and Champlain were to sail as convoy escorts from Montreal on 16 July 1936, with Champlain detaching after the convoy passed Quebec City. Naval authorities were not able to provide the officer commanding Saguenay, Commander W.J.R. Beech, RCN, with particularly detailed instructions, but ordered him to “use his own judgment and act as circumstances require. He is to rely on advice received from the Canadian Legation and the responsible officials in charge of the Vimy Memorial.”7

In mid-July, Saguenay was docked at Montreal, along with the older destroyer HMCS Champlain, in preparation for the departure of the pilgrims for overseas. During its stay at Montreal, Saguenay landed the members of the Royal Guard twice in order to practice their drill. The commander of the local militia district, Brigadier R.O. Alexander, DSO, witnessed the first practice and took the salute as the guard marched past upon completion of the drill. At some point in this period, the warship was painted, and she was cleaned throughout. On 15 July, Commander Beech and the rest of the ship’s officers held an ‘at home’, welcoming the captains and officers of the ocean liners composing the convoy that was to transport the pilgrims to Europe.8

At 1045 hours on 16 July, the two warships escorting the convoy departed Montreal. The Cunard White Star liners Antonia and Ascania, and the Canadian Pacific Railway liners Montcalm and Montrose, closely followed them. HMCS Champlain sailed only as far as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where she detached for other duties. The next week was uneventful for the crew of the Saguenay, signals work and gun laying and training exercises being carried out in addition to routine duties. The ship reported “fine and clear weather” for the trans-Atlantic journey until it reached the coast of Ireland, where a gale brought on “rain and poor visibility.” Saguenay left the liners on the evening of 23 July and arrived off the entrance to the harbour of Boulogne, France, at 0500 hours the following day.9

After the arrival of Saguenay in port in the early afternoon of 24 July, Commander Beech made his formal visits ashore and met the captain of the French destroyer Orage, which was to act as the “host ship” to the Canadian destroyer and to escort His Majesty’s transport off Calais on its way to the cemetery. Events would later prove that neither destroyer would escape the Second World War unscathed. Orage was severely damaged by German aircraft off the coast of Boulogne during the evacuation of Dunkirk, and sank early on 24 May 1940 (with the loss of 28 sailors), while Saguenay was damaged by a collision with a civilian freighter on 15 November 1942, resulting in internal explosions that destroyed her stern, to the extent where she was capable of only training duties after being repaired.10

The Royal Guard represented roughly one-third of the Saguenay’s entire complement and consisted of three officers, three petty officers, and 60 ratings (sailors). The Officer of the Guard was Lieutenant (later Rear-Admiral, OBE) Hugh Francis Pullen, RCN, while Lieutenant Morson Alexander Medland, RCN, served as the Colour Officer (the guard carried a white naval ensign ashore with it) and Gunner (T) Patrick David Budge, RCN, served as the Second Officer of the Guard. The three petty officers were Robert Brownings (who formed the right guide), Charles J. Kelly, and Frederick W. Saunders (who, by 1953, was a chief petty officer honoured with the George Medal and the Distinguished Service Medal). The remainder of the guard incorporated five leading seamen, two leading stokers, 30 able seamen, 11 stokers, 10 ordinary seamen, one signaller, and one telegraphist, all of whom were RCN regulars. An additional petty officer and two sailors travelled with the guard as backups, sailors available to fill any gaps in the guard brought about by sickness or other causes. As it materialized, the three extra men were not needed, and they were lent to the Canadian army representatives at the memorial to act either as messengers or for secondment to other duties.11

DHH 81/520/1000, box 158, file 5

His Majesty King Edward VIII escorting the French President to the memorial on the day of the ceremony, passing between the Canadian veterans’ contingent and the Royal Guard in the background and the French military band and Algerian spahis in the foreground.

Getting Ready

Lieutenant Pullen issued orders on 24 July for the members of the Royal Guard with respect to clothing, equipment, and timings for the following day’s departure. He ordered each member of the guard to have packed their No. 1 Dress – their ceremonial uniform – as well as cleaning materials and spare items. Upon departing Saguenay the men would wear their No. 2 Dress, which was less formal than their No. 1s, but more so than their daily working dress, as well as their “best boots.” All members were to be awake by 0530 hours and fall in on the jetty by 0630 for the departure for Arras half an hour later.12

At 0630 hours on Saturday 25 July 1936, the Royal Guard formed up on the docks abreast of HMCS Saguenay. All three officers were wearing No. 3 Dress, “which, to the uninitiated, consisted of cocked hat, frock coat, epaulettes and sword, the uniform then worn on ceremonial occasions.” The guard then marched off to the railway station in Boulogne, immediately boarded their train, and left Boulogne at 0706 hours. Its destination was the city of Arras, the nearest large municipality to Vimy Ridge, where it arrived at 1032 hours. A Canadian army officer met the guard and provided the sailors with information concerning timings and their accommodations.13

Here, the Royal Guard met up with its counterparts for the unveiling ceremony as the guard was marched out of the Arras railway station, bayonets fixed, led by 29 members of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery Band from Kingston, Ontario, a composite military pipe band of 20 pipers formed for the ceremonies “from every Highland regiment in Canada,” eight trumpeters and buglers, and 11 drummers from the 48th Highlanders of Canada garrisoned at Toronto. The route from the station to the Town Hall in Arras, their destination, was reportedly “lined with civilians who received the Royal Guard with enthusiasm.” Lieutenant Pullen noted the “considerable enthusiasm among the inhabitants, who had not seen Canadians under arms since the bitter days of the First World War.” At the Town Hall, the guard and the bands were brought inside to hear an “address of welcome” from the city’s mayor and to be entertained. As part of the ceremony, Lieutenant Pullen replied, somewhat hesitantly, to the mayor’s welcome en français. He later wrote that any “awkward feelings were soon allayed, however, by generous glasses of champagne.”14

Following the ceremony, the non-commissioned members of the guard and the bands were bussed off to a local school where they were being billeted, the accommodation being officially described as excellent, “while the messing arrangements and quality of the food could not have been better.” The officers, meanwhile, were staying at the Hotel du Commerce in Arras, “where every kindness was shown them by the proprietor and staff.”15

At 1400 hours, the guard and the bands were taken to Vimy Ridge by bus to carry out a rehearsal for the next day’s ceremony. The buses were late, in what would become an ongoing problem. Traffic was also heavy, as the troops were sharing the area with pilgrims and French citizens gathering for the following day’s activities. As a result, it took one-and-a-half hours for the contingent to travel the 14 kilometres or so from Arras to the memorial. Already late, things went from bad to worse when the rehearsal was inundated by heavy rains that “washed out all hope of accomplishing much.” At 1700 hours, the rehearsal was cancelled. The cancellation at least allowed the members of the guard to take an appreciative look at the new memorial, and many photographs were taken. On the way back to their buses, the sailors were also allowed to examine “the trenches, tunnels, etc with great interest and [they] arrived at their billets tired but satisfied.” While some of the guard went out on leave until 2300 hours, its officers attended an evening conference held by Lieutenant-Colonel G.E.A. Dupuis, MC, (Royal 22e Régiment), the overall contingent Officer Commanding Troops (including the royal guard, bands, and staff personnel), where the details of the ceremony were discussed and finalized.16

DHH 81/520/1000, box 158, file 5

The Royal Guard at attention at the Vimy Memorial during the rehearsal the day before the unveiling ceremony.

The Big Day

On Sunday morning, 26 July, Lieutenants Pullen and Medland and Mr. Budge accompanied Lieutenant-Colonel Dupuis to Arras Station to meet representatives of the Canadian Government, as well as delegates from Belgium. Meanwhile, the rest of the guard spent the morning cleaning their kit and preparing for the ceremony. Lunch was held at 1130 hours, and all members were ready to march off at 1300 hours. Again, the buses were late in arriving and the guard and the bands only reached Vimy Ridge around 1330 hours, leaving them with just enough time to fall in and march to their positions in front of the memorial “without time even for a brushup.”17 The guard took up position perpendicular to the entrance side of the memorial while the area around the site continued to be “covered with pilgrims and other visitors from near and far.” A French military band and a guard of Algerian cavalry, spahis, on white horses were positioned facing the Royal Guard (the Canadian musicians were situated behind the guard).18

The ceremony began at 1415 hours, with the Royal Guard being ordered to slope arms in preparation for the arrival of His Majesty King Edward VIII. The guard then gave the royal salute, and the band played “God Save the King” and “O Canada.” Next, The King inspected the Royal Guard, which had now ordered arms, while the band played “Heart of Oak” and “Boys of the Old Brigade.” During this “very proud moment in our lives,” King Edward reportedly asked numerous questions about the sailors, how long they had served, and what their nationalities were. Presentations were made in front of the monument and the guard was ordered to stand easy, while the King inspected the assembled veterans and the military band continued to play.19

Within 15 minutes, these initial actions were completed. The guard was ordered to slope arms while the King moved to receive the French President, Albert Lebrun, at the ceremony. The guard presented arms while the president arrived and the band played “La Marseillaise.” The guard then returned to sloped arms. At 1452 hours, the third phase of the ceremony began, with the King and the French President passing the guard on the way to the monument, the guard with ordered arms, and the band playing “Abide with Me.” The guard then assumed a stand easy position as speeches and a playing of “Flowers of the Forest” by the bagpipes consumed the next half hour of the ceremony. Having completed his speech, the King unveiled the monument, the guard coming to attention. The “Last Post” was played, followed by a moment of silence, before “reveille” was sounded. The French president made the final speech, followed by the band playing “Land of Hope and Glory” at approximately 1534 hours. The ceremony ended over the next few minutes, the guard sloping arms, then giving the royal salute while the band played, and the King and the French president left the presentation area. The Royal Guard was ordered to stand at ease, more than two hours after stepping into place.20

DHH 81/520/1000, box 158, file

His Majesty King Edward VIII departing the unveiling ceremony. Lieutenant Pullen, RCN, can be clearly seen over the King’s left shoulder in command of the Royal Guard.

At some point during the ceremony, the guard also came to attention when Rear-Admiral Walter Hose, CBE, RCN (ret’d) and several French generals passed by their position. The former head of the Royal Canadian Navy “expressed his pleasure at seeing the Guard and their steadiness.” He was not alone. Lieutenant Pullen noted in his post-ceremony report that, after the completion of the event, “numerous people made complimentary remarks concerning the Guard.”21

With the ceremony over, the next stage in the plan was for the guard to march over to the west side of the memorial for a group photograph and a wreath laying. However, as Pullen noted, the sailors were “well nigh swamped by the spectators [and] stood fast,” making the process very difficult. In fact, it made the plan impossible to execute and, at 1620 hours, the guard and the bands were marched off the memorial.22

The guard and the bands then moved down to a Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery on the western slope of Vimy Ridge, either Givenchy-en-Gohelle Canadian Cemetery or Canadian Cemetery No. 2, there is no clear indication which, to carry out a “short unrehearsed ceremony.” The guard gave a General Salute while the bands played. Last Post and Reveille were “sounded off by the Naval Bugler,” Able Seaman Henry Bayley, then a wreath was carried forward by an able seaman and a leading seaman stoker, supported by an ordinary seaman and an ordinary stoker, all led by Lieutenant Pullen. The ceremony ended with the guard and bands marching off the cemetery before falling out. “This opportunity was seized to inspect the cemetery which was most beautifully kept.”23

W.W. Murray, comp. and ed., The Epic of Vimy Ottawa:

The Legionary, 1936), p.66

An overhead shot of the Vimy Memorial on Sunday, 26 July 1936, before the arrival of His Majesty The King. The Royal Guard can be seen standing between the two columns on the side of the memorial where His Majesty would arrive.

At 1745 hours, the guard and bands fell in and marched off towards the Main Road in order to catch the buses back to Arras. As Rear-Admiral Pullen would note in 1953: “After our two previous experiences, we should have known better.” Unreliable bus drivers and the heavy traffic were blamed for the failure of the buses to appear and, after a one-and-a-half hour delay, it was decided to march the Canadian contingent back to Arras. Pullen noted: “The decision wasn’t made lightly, for we had been without food, water or tobacco since 1300 [hours].” This lack of sustenance was at least partly compensated for by the availability of bread and cakes being sold by local citizens at the base of the ridge, the tables being reportedly bare by the time the last Canadian sailor had passed by. Led by the two bands, the guard marched out of the cemetery for Arras, travelling through Neuville-St-Vaast and La Targette along the way. Local villagers in Neuville-St-Vaast gave the sailors and musicians water, as did others further along the route. Rear-Admiral Pullen later had pleasant memories “of the setting sun and the lengthening shadows and the two pylons of the memorial gleaming white and tall on the crest of Vimy Ridge.” As the contingent crested the hill leading down into Arras, the pipes and drums started playing “The Road to the Isles” and the group marched on, “heads up, arms swinging.” The trip to their billets had taken two-and-a-half hours, with Pullen proudly recording: “Not a man fell out and the party marched into Arras singing.”24

The contingent’s delayed arrival in Arras meant they had missed the last train of the day to Boulogne, and therefore, arrangements were made for them to remain another night. Finally, at 0802 hours on Monday, 27 July, the guard and the bands left Arras. The train trip was described as, “more than somewhat relaxed. Sailors and Highlanders traded caps and bonnets and danced to the pipes on the railway platform. The effect on the local inhabitants [was] somewhat startling.” The train arrived in Boulogne at 1032 hours, where the contingent formed up “with bayonets fixed, drums beating, and colours flying” and marched through the streets, arriving alongside HMCS Saguenay a little after eleven o’clock. Lieutenant-Colonel Dupuis then addressed the sailors, and the guard responded by giving him and the bands “three hearty cheers.”25

VA

The refinished Memorial in the spring of 2007.

Afterthoughts

In his report of proceedings for the pilgrimage, Lieutenant Pullen noted that cooperation between the navy and army had been excellent, and that it had been “a great honour” to serve under Lieutenant-Colonel Dupuis. In fact, the contingent did not disband immediately at this point. With “a great deal of forethought,” First Lieutenant George Ralph Miles onboard Saguenay had made sure that a “suitable stock of Canadian beer” had been loaded aboard the destroyer before leaving Canada. As a result, the navy was able to entertain the army “in an appropriate fashion” before the bands and army staff left to catch their boat to the United Kingdom. Eventually, the troops left, the pipe band marching off to “The Cock o’ the North,” as the sailors cheered them away.26

Lieutenant Pullen’s assessment of the Royal Guard under his command was no less flattering. He noted the conduct of its members “was excellent in every way. They stood for two and a half hours during the ceremony without a man fainting and then marched approximately eight miles back to Arras, having had no food for nearly ten and a half hours.” He also wrote the “standard of the uniforms” in the guard was high, it would seem largely because all of the sailors had gone “to considerable expense” to buy new uniforms, boots, caps, and badges. Nearly 20 years later, Pullen had lost none of his praise, writing: “The guard not only underwent vigorous and intensive training, but each officer and man went to considerable expense to provide himself with a new uniform that he might offer a creditable appearance.” This was particularly commendable, given that the ceremony took place in the midst of the Great Depression in an era where military pay was not particularly high.27

Commander Beech, officer commanding the Saguenay, also noted his great satisfaction with the members of the Royal Guard, describing it as “a credit to the Royal Canadian Navy. Many distinguished personages remarked on the steadiness and smartness of the Guard. I consider that Lieutenant H.F. Pullen, R.C.N., deserves great credit for the manner in which he trained and commanded the guard.”28

Their ceremony completed, the ship’s crew returned to normal duties and HMCS Saguenay sailed out of Boulogne harbour late that afternoon for England.29

![]()

Ken Reynolds, PhD, is the Assistant Canadian Forces Heritage Officer with the Directorate of History and Heritage in Ottawa.

Notes

- My thanks to Captain Steve Gannon (ret’d), Ms Amanda Kristensen, and Major Paul Lansey from the Directorate of History and Heritage, Department of National Defence, and Philip L. Hartling and staff at the Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management (hereafter NSARM) for their assistance with this paper.

- Cited in Herbert Fairlie Wood and John Swettenham, Silent Witnesses (Toronto: Hakkert, 1974), p.64.

- W.W. Murray, The Epic of Vimy (Ottawa: The Legionary, 1936), pp.11, 65.

- Pierre Berton, Vimy (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1986), p.303.

- Directorate of History and Heritage (hereafter DHH) 81/520/8000, Box 90, File 2, HMCS SAGUENAY I, “River” Class Destroyer, Volume 1, Naval Historical Section, 13 March 1958, “Brief History of HMCS SAGUENAY”, pp.1, 3.

- DHH 81/520/8000, Box 90, File 2, HMCS SAGUENAY I, “River” Class Destroyer, Volume 1, Naval Historical Section, 13 March 1958, “Brief History of HMCS SAGUENAY”, p.3; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” The Crowsnest, Vol.5, No.11 (September 1953), p.14.

- NSARM, MG 1, Vol. 2526, Item 44, “The Unveiling Ceremony at Vimy Ridge, July 1936”, J.O. Cossettee, Naval Secretary, to The Commander (D), East Coast Sub-Division, H.M.C.S. “SAGUENAY”, 3 July 1936.

- DHH 81/520/8000, Box 90, File 5, HMCS SAGUENAY I, Reports of Proceedings (1931-1940), Report of Proceedings, HMCS Saguenay, 13 July to 1 August 1936 (hereafter Saguenay Report of Proceedings), paragraphs 2-5.

- Saguenay Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 6-10; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” The Crowsnest, Vol.5, No.11 (September 1953), p.14; DHH, Kardex 000.8 (F 61), Booklet entitled “With the Tenth Field Company Canadian Engineers C.E.F. in 1936”, The Vimy Pilgrimage, H.S. Turner, “With the Tenth Field Company Canadian Engineers C.E.F. in 1936,” p.3.

- Saguenay Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 11-15; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” The Crowsnest, Vol.5, No.11 (September 1953), p.14; David Brown, Warship Losses of World War Two (London: Arms and Armour, 1990), pp.33, 75.

- DHH 81/520/8000, box 90, file 5, HMCS SAGUENAY I, Reports of Proceedings (1931-1940), – Report of Proceedings of the Royal Guard landed from H.M.C.S. “Saguenay” at Boulogne on Saturday 25th July, 1936, Lieutenant H.F. Pullen, R.C.N, Officer of the Guard, to The Commanding Officer, H.M.C.S. “Saguenay” (hereafter Royal Guard Report of Proceedings), paragraph 2; ibid, Appendix II, Composition of Royal Guard; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.14. In his personal papers, now at the Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management, and in his 1953 article in The Crowsnest, Rear-Admiral Pullen listed the names of all of the members of the guard (in addition to the six officers and petty officers named in the text): Leading Seamen Jonathan Carswell, Ralph E. Gregory, Charles L. McDerby, Gérard Normandin, and John G. Ross; Leading Stokers Ernest Racine, and Frederick H. Watt; Able Seamen Jean Arsenault, Frank E. Aves (he retired as a chief petty officer with a British Empire Medal), Henry B. Bayley (bugler), Albert Clarke, George J. Corp, Dosithé Desjardins, Delbert K. Dorrington, Robert L. Ellis, Daniel W. Gearing, Frank L. Gervais, Fred J. Granger, Sydney C. Hancock (died aboard HMCS Margaree 22 October 1940), James C. Harris, Stanley A. Ireland (drowned during Saguenay’s visit to the Channel Islands on 29 July 1936), Jack W. Johnson, Alex T. Kirker, Lorenzo J. Lafrenière, Reginald E. Leal, Herbert S. Lentz, Jack Marcus, Aubrey F. McGee, Walter B. Nichol, Leslie J. Parry, Ernest E. Pinter, Charles W. Ponder, Frederick E. Ross, Nelson D. Rutt, James R. Trow, Albert E. Veal, and Albert J.B. Wolfe; Stokers Weldon P. Bryson, Arthur F. Carter, Walter J. Clapp, Edward Glover, James F. Mackintosh, Angus I. MacMillan, Mitchel E. Perrin, Harry L. Priske, Terrance D. Riordan, George H. Soublière, and George E. Speck; Ordinary Seamen Douglas R. Clarke, Renfred C. Heale (died aboard HMCS Margaree on 22 October 1940), Dominic R. Hill, Douglas A. Kershaw, Robert E. Middleton, James W. Paddon (died aboard HMCS Fraser on 25 June 1940), Ellis McP. Parker, Helge Pohjola, William H. Roberts (retired as a chief petty officer in 1953, with an RCN Long Service and Good Conduct Medal and the American Legion of Merit), and Lenn Speight; Signaller Franklin M. Macklin (died aboard HMCS Fraser on 25 June 1940); and Telegraphist Donald McGee. NSARM, MG 1, Vol. 2526, Item 44, “The Unveiling Ceremony at Vimy Ridge, July 1936”, “Nominal List of Guard, 1936”; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” pp.16-17.

- NSARM, MG 1, Vol. 2526, Item 44, “The Unveiling Ceremony at Vimy Ridge, July 1936”, Lieutenant (G) H.F. Pullen, R.C.N., “Royal Guard – 1936.”

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 3-4; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.14.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 5-6; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” pp.14-15. Extant documents note Lieutenant F.W. Coleman directed the RCHA Band, a group that included Band Sergeant H.N. Longshaw, 28 musicians (all but two were RCHA), and seven buglers drawn from different regiments and corps; and, the composite pipe band was led by Pipe Major S.H. Featherstone (The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s)) and included representatives from numerous regiments. DHH, Kardex 324.009 (D40), Corresp, instrs, reports, etc to & by veterans organizations in MD 5 incl corresp re Vimy pilgrimage of 1936, d/Apr 20/Jan 41, volume 3, Memorandum, Vimy Pilgrimage – 1936, C.F. Constantine, Major-General, Adjutant-General, to District Officers Commanding, Military Districts Nos. 4 and 5, 8 July 1936; Ibid, Nominal Roll – Vimy Pilgrimage 1936, Personnel Sailing S.S. Duchess of Richmond – July 10th; Ibid, Nominal Roll – Vimy Pilgrimage 1936, Personnel Sailing S.S. Empress of Britain – July 11th, 1936.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, para-graphs 7-8; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 9-12; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 13-15; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, Appendix Number I, Timetable; Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraph 17; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, Appendix Number I, Timetable; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 18-19; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraph 20; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraph 21; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.15; Herbert Fairlie Wood and John Swettenham, Silent Witnesses (Toronto: Hakker, 1974), pp.54, 56.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 22-23; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” pp.15-16.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 24-25; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.16.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 27-28; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.16.

- Royal Guard Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 26 and 29; H.F.P., “The Pilgrimage to Vimy Ridge,” p.14.

- Saguenay Report of Proceedings, paragraphs 11-15.

- Saguenay Report of Proceedings, paragraph 16.