This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

History

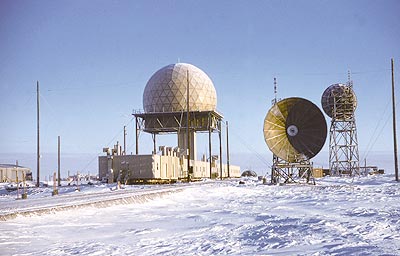

DND photo

A completed DEW Line radome, circa 1956.

The Distant Early Warning Line and the Canadian Battle for Public Perception

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

In December 1954, construction began on the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, an integrated chain of 63 radar and communication centres stretching 3000 miles from Western Alaska across the Canadian Arctic to Greenland.1 This predominantly-American defence project, designed to detect Russian bomber incursions into North American airspace, was the largest technological undertaking the Canadian Arctic had yet witnessed. The DEW Line was only one in a series of defence projects that Canada and the United States had jointly embarked upon in the Far North since the Second World War. However, the sheer magnitude and unprecedented expense of the project, coupled with Canada’s inability and disinclination to contribute to it, was widely seen as presenting a greater challenge to Canadian Arctic sovereignty than anything that had happened earlier in the region. The source of Canadian anxiety over Arctic sovereignty was the lack of any substantial physical Canadian presence there. While there were few serious fears of an official American usurpation of Canadian territory, there were serious concerns for loss of de facto control over that territory. It was reasoned that a large, unilateral American construction project in the North would inevitably result in the United States military exercising effective control over the region. The Americans would administer the territory, would guard it, would observe from it, and, given the local demographics, would effectively populate the region. While Canada might retain legal title to the land, this assertion of de facto control by a foreign state would have fundamentally undercut the image of Canadian sovereignty in the North, both domestically and internationally. To avoid the impression that any abdication of sovereignty had taken place, and to avoid actually investing heavily in the DEW Line itself, the Canadian government’s principal aim in dealing with the construction and operation of the Line became one of maximizing the perception of Canadian control and influence. Canadian policy focused upon the pursuit of appearance over substance, with the promotion of an idea rather than the pursuit of its physical embodiment becoming its primary objective. It was this battle for perception that became the driving force and the ultimate end-state of Canadian policy with respect to the DEW Line, from its inception to its manning during the 1950s.

What is Sovereignty?

The idea of sovereignty is an amorphous and multifaceted concept that has evolved throughout history to suit the various circumstances of the day. At its core lies a single principle: The possession of supreme authority expressed through the legitimate monopoly over physial force within a given territory.2 However, a holder of sovereignty must possess more than mere cohersive power. There must also exist legitimacy, what philosopher R.P. Wolff called “the right to command.”3

Fundamental to legitimizing sovereignty is the fact that a state’s right to control its territory is recognized and accepted by the international community. To this end, therefore, sovereignty must be derived from some mutually acknowledged source of legitimacy, which, historically, has ranged anywhere from a divine mandate to modern international law.4 When a state’s right to control territory is recognized by the larger global community, it essentially has been given a guarantee against external intervention within that teritory, and, ipso facto, is left with absolute authority, if not necessarily in practice, then at least in theory. Sovereignty is thus a two-headed creature. On one hand, force and control lie at its heart; it is from them that sovereignty flows, from them that it is enforced, and largely because of them that it is recognized. But the actual exercise of this force cannot be considered sovereignty per se, only its manifestation. It is only with the recognition of others of one’s right to use force, or, at the very least, with the absence of any challenges to that right, that sovereignty can be deemed to exist. Sovereignty is thus, at its very essence, an imagined concept, existing only in the minds of those that recognize it. It is this concept, the recognition that the Canadian Arctic is Canadian by virtue of tradition and international law, that the Canadian government fought for more than anything else to defend against American encroachment.

DND photo

A Soviet Tu-95 Bear bomber.

Background

In 1949 and 1953 respectively, the Soviet Union detonated its first plutonium and hydrogen bombs. When mated with the then-new (1952) Soviet Tu-95 Bear bomber, and, to a lesser extent, the even earlier (1946) Tu-34 Bull bomber, many centres of industry and high-density population in North America had fallen within range of Soviet nuclear weapons.5 This series of genuinely revolutionary changes in military technology and strategic concepts had catapulted the Canadian Arctic from the strategic backwaters to the forefront of Cold War defence.6 In this new strategic paradigm, the Canadian Arctic had assumed the role predicted for it by Hugh Keenleyside in 1949, when he said: “What the Aegean Sea was to classical antiquity, what the Mediterranean was to the Roman world, what the Atlantic Ocean was to the expanding of Europe of Renaissance days, the Arctic Ocean is becoming to the world of aircraft and atomic power.”7 The Cold War had placed the Canadian Arctic under the spotlight and given it a new and unwelcome importance.

The DEW Line was a direct reaction to this emerging Soviet threat. Militarily, a northern radar line made sense from the Canadian perspective. While previously there had never existed any serious concern with respect to a major Soviet attack on the North, it was assumed that because of the close geographical proximity of Canadian and American industrial and population centres, as well as their close military and political connections, these two nations would share the same fate if a full-scale nuclear war were to erupt. Yet, the idea of any American activity on Canadian soil, however beneficial, made Canadian politicians nervous.

When the American plan for the DEW Line was forwarded to the Canadian government, Ottawa found it had little diplomatic choice in the matter. The Minister of National Defence, the Honourable Brooke Claxton, put it succinctly in a telegram to Secretary of the Cabinet Arnold Heeney when he wrote: “It may be very difficult indeed for the Canadian government to reject any major defence proposals which the United States government presents with conviction as essential for the security of North America.”8 The Canadian government, still under the obligations which it had accepted at Ogdensburg in 1940 when Prime Minister Mackenzie King had assured the Americans, “...[that] the enemy should not be able to pursue their way, either by land, sea, or air to the United States across Canadian territory,” could not conceivably refuse the American request to construct the Line.9 Under the military and political circumstances of the day, the construction of the DEW Line, as a rational continuation of continental defence, was almost inevitable. Canada was thus forced into the highly uncomfortable position of choosing between playing a large role in the construction of the Line and accepting a massive influx of American influence into its Arctic region, which could bring into question its ability to exercise effective control over its own neglected territory.

DND photo

The response. A CF-100 Canuck all-weather interceptor overhead RCAF Station Cold Lake in winter.

Challenges to Sovereignty

Nearly a century of general indifference on the part of successive Canadian governments had left the region lacking an adequate military or civilian infrastructure, significant economic development, or adequate supervision. Coupled with an extremely sparse population, the physical manifestations of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic were scarce. However, the United States was not interested in acquiring Canadian territory. This fact was amply demonstrated by the American Arctic projects of the Second World War, which had “scrupulously avoided” violating Canadian sovereignty.10 Canadian concern arose instead from the threat to Canada’s de facto sovereignty, which would be called into question if American forces were seen to be exercising authority over Canadian territory. In 1931, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) had ruled that it was the exercise of authority within a territory that was the principal consideration when dealing with matters of sovereignty. This control even superseded prior claims to discovery or contiguity.11 Without more physical control over the Arctic, there were serious concerns that Canadian claims, which were based upon discovery and contiguity, might be invalidated in the minds of both its own public and the international community if the United States was seen to be exercising effective control over the region.

Given the sparse population of the area, a large influx of American servicemen and civilian contractors would shift Arctic demographics, and the North would become more American in terms of a human presence. Americans would become responsible for the execution of the duties and responsibilities that were properly Canadian.12 With physical manifestations of sovereignty under foreign control, Canadian sovereignty would be eroded in the minds of anyone who looked north and saw that the real authority in the region was, in fact, if not in law, American.

DND photo

The Canadair F-86 Sabre was also a useful day fighter interceptor of the era.

What to do?

With little physical presence to represent Canadian control, American domination in the North would be all too obvious, and the fear in Ottawa was that once the international community began to believe that the Arctic was under American control and administration, Canadian sovereignty would weaken accordingly. Damage control was therefore always at the core of Canadian policy surrounding the DEW Line. First and foremost, Ottawa endeavoured to control how people perceived the project and American involvement in the North. It was vital to the government that the image of Canadian control be maintained, even when that control was, in practical terms, being delegated to the United States. For this reason, the Canadian government spent a great amount of effort dealing with perception and publicity. Minor incidents, the wording of agreements and press releases, anything that might affect public opinion, was carefully managed and ‘spun’ to maximize the image of Canadian participation in, and even control over, the DEW Line, while minimizing the appearance of American control over Canadian soil.13

This effort was extensive and comprehensive, and it dated back to shortly after the Second World War. To minimize the US military profile in Canada, the Department of External Affairs went as far as to insist that United States Air Force (USAF) stations in Canada, when and where required, not be established near any major population centres. It was also requested that USAF offices be set up as annexes to American consulates, or even located inside Department of National Defence offices, rather than establishing separate facilities.14 The offices, if they had to be established, were to be kept “inconspicuous,” and the personnel, who were asked to wear civilian clothes, were to tell inquirers that they were “working on joint classified projects of the USAF and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).”15 In the opinion of one American bureaucrat, “[t]he attempt to cover up the fact that US forces are in Canada has at times involved ludicrous limitations.”16 These conditions were a sign of Canadian insecurity over the idea of being perceived as an unequal partner to the US, or worse, as a recipient of American aid. This insecurity was even more pronounced in the North, where local conditions gave American forces significance and a visibility disproportionate to their numbers.17

Ottawa had been careful to avoid giving the impression that American assistance constituted ‘aid’ of any kind, and activities in the North were no exception.18 Trivial incidents, ranging from an American refusal to allow an RCAF aircraft to land on one of their Canadian airfields, to the damaging of an Inuit archaeological site by US servicemen, were often enough to raise great concern in Ottawa.19 Every American action that gave the appearance of American disregard for Canadian sovereignty in the North, no matter how trivial, made an insecure Canadian government even more insecure. Most of these incidents were petty; but they epitomized the Canadian fear of the Arctic under de facto US military control. The government’s policy was thus marked by a push to suppress these incidents in an attempt to hide its anxiety behind a mask of false confidence, worn for both Canadians and the world.20

To lessen the appearance of American hegemony in the North, an effort was made to use the terms ‘joint-project’ and ‘cooperation’ at every possible occasion. When the DEW Line became operational in 1957, Canadian policy was to place Canadian officers in as many command positions as possible. While the ultimate command of the system rested with the USAF, the appearance of Canadians in positions of authority helped to encourage the impression that the DEW line was not solely under American control. Yet, while the agreement governing the establishment of the DEW Line gave Canada the right to man the stations, there was never enough trained manpower in the RCAF to accomplish the task.21 What men Canada did post to the DEW Line served more as symbols of national control and occupation, and they were a vital part of the government’s drive to reinforce the image of a Canadian presence. In 1959, in a speech to Parliament, the Minister of National Defence, George Pearkes, used the presence of the few RCMP officers in the region to give the impression of Canadian occupation. He said: “Everywhere you go at all these stations on the DEW line you now see the scarlet coat of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.”22 Yet, at the time, there were fewer than 200 RCMP officers spread across the entire Canadian North.23

According to an External Affairs report of the period: “The main purpose of Canadian participation is to make it clear to the people of Canada that the United States is not being permitted to carry out large projects in Canada except under effective Canadian control.”24 This policy is accurately summarized by a 1954 government Guidance Paper, which states:

... [that it is] important that the rest of the world should be aware that the Canadian Arctic is not an ‘Ultima Thule’ but is being effectively occupied, administered and developed by the Canadian Government and people. This emphasis should underline all public information on the north whether it relates to long-range policy plans or spot news.25

The Canadian response to the influx of Americans into its Arctic was thus primarily psychological, with Canadian participation principally designed to convey the image, rather than the substance, of Canadian control.

Canadians have generally been amenable to multilateral forms of cooperation. Part of the anxiety generated by the DEW Line was that American forces in the North gave the impression of Canadian sovereignty being usurped by a clearly defined foreign power. As such, from an early date, the Canadian government strove to link the DEW Line with multinational institutions. In March 1955, while on a visit to Washington, Lester B. Pearson, Canada’s then-Secretary of State, suggested to his American colleagues that the Arctic become a NATO region. He even went so far as to propose that European states be asked to provide troops to man the Line, personally suggesting the deployment of 200 to 300 Dutch service personnel.26 While, for political and military reasons, the DEW Line was never integrated formally into NATO, and there was no “multilateral command,” as the influential Winnipeg Free Press had suggested, there was a push to minimize the impression of American hegemony in the North by attempts to place the DEW Line into a multilateral paradigm within which Canadians had traditionally been more comfortable.27 Very early on, Canadian government publications began linking the DEW Line to NATO, to collective security, to the United Nations, and even to world peace. This was not a new tactic, nor would it be the last time it was employed to make a bilateral agreement with the United States sound more appealing. The joint statement made by the Canadian and American governments concerning the completion of the Pinetree Line, and the start of construction on the DEW Line in 1954, illustrate this attempt to place a fundamentally bilateral defence arrangement within a more comfortable multilateral context:

The defence of North America is part of the defence of the North Atlantic Region to which both Canada and the United States are pledged as signatories of the North Atlantic Treaty. Thus the cooperative arrangements for the defence of this continent and for participation of Canadian and United States forces in the defence of Europe are simply two sides of the same coin, two parts of a world wide objective, to preserve peace and defend freedom.28

In 1959, the Report on National Defence by the Minister of National Defence linked the radar warning lines not only to NATO and the preservation of world peace, but also attempted to link the DEW Line to the United Nations.29 In public statements, a concerted effort was made to ensure that the DEW Line was not looked upon as an isolated project. The notion that it was a NATO project, or was at least connected to NATO or UN policy, served to balance the American presence in the Canadian Arctic, since, at that time, a Canadian brigade and an air division were similarly deployed on the territory of France, another NATO ally.

And yet, the DEW Line sites differed from the NATO military bases spread across Europe. The NATO establishments in Europe were paid for by all members, not just single states, as was the case with the Arctic sites.30 In this manner, the appearance of control by a foreign nation was diluted in the European context. Most importantly to the Canadian Cabinet, however, was the fact that NATO’s European bases were located in heavily populated areas,

“...[and] represent a small fraction of the sum total of human activity in those areas and thus did not in any sense constitute a threat to the sovereignty of the states within which they were located, whereas it was just within the realm of possibility that in years to come US developments might be just about the only form of human activity in the vast wastelands of the Canadian Arctic.”31

There had been calls, both in the House of Commons and within the Department of External Affairs, to invest the time and resources in the Arctic that would have allowed Canada to exercise more than a token amount of physical control, and would avoid surrendering the area to the Americans.32 However, these were largely “voices in the wilderness,” as the overwhelming majority of politicians and bureaucrats balked at the costs of equal (or even meaningful) participation in the DEW Line. Yet, this reaction to the expense of the DEW Line was certainly not unreasonable. The total Canadian defence budget for 1953-1954 was only $1.8 billion, and to undertake even a 50 percent share in the project would have required roughly a 6 percent increase in defence expenditure. Given that in 1953, Canadian defence expenditure already accounted for fully 50 percent of all government spending and 10 percent of the GNP, at a time when the nation was in a mild economic downturn, such an increase would have been politically, if not economically, unworkable.33 That estimate also assumed the correctness of the $200 million figure quoted for construction of the Line to the American government by Western Electric, a private firm anxious to win a lucrative contract. Many in Ottawa felt that the Americans were not “fully aware of the magnitude of the problems involved” in Arctic construction, and there was a strong suspicion that the final costs would end up being far more than the US government had predicted.34 The correspondence between the Department of External Affairs and the US government clearly demonstrate Ottawa’s aversion to becoming committed to this risk. Canada’s decision to allow the United States to pay for the project in its entirety should not necessarily be considered as a shirking of its national responsibilities. Indeed, given that by the time of the Line’s completion in 1957, unconfirmed rumours put the overall cost for construction (excluding equipment and transportation) at more than $750 million, the Canadian decision to abstain appears to have been prudent and farsighted.35 Instead, Canada focused its limited resources upon a project it deemed a more cost effective way to offset the image of the DEW Line as a Canadian abdication of its defence responsibilities.

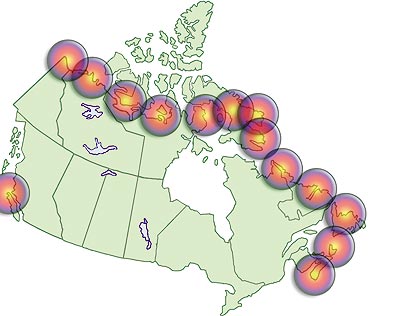

• DEW Line Radar Stations

• MID Canada Line Radar Stations

• Pinetree Line Radar Stations

Map by Christopher Johnson

The trio of early warning radar lines, as they ultimately emerged.

The Mid-Canada Line

The Canadian construction of the Mid-Canada line (or McGill Fence) was a cost-effective attempt to dilute the appearance of American control in the Arctic. In 1954, the same year that the Canada-US Military Study Group officially recommended the construction of the DEW Line, the Canadian government undertook sole responsibility for the construction of a radar line to run roughly along the 55th Parallel. The Mid-Canada Line, a project of questionable military value, was supposed to complement the DEW Line to the north, and the Pinetree Line to the south.36 Concerns with respect to American control in the Arctic had played a large role in the Canadian government’s deliberations over how, or even if, this line should be constructed.37 In 1953, Brooke Claxton had written to Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, advising him in favour of constructing this radar line, and suggesting that it be done independent of American assistance. For Canada to build the Mid-Canada Line alone, he argued, would provide a counter to the American building of the DEW Line, and it would be cheaper than joint cooperation in the Far North. An entirely Canadian built and manned radar line would allow Ottawa to boast:

“ Well, we think we have done what we thought was necessary for continental defence. If you want to go on and do more we are not going to stand in the way and keep our self respect without having to put out too great an expenditure of materials, manpower and money... It would enable us to tell our own people and the Americans that we were quite prepared to do anything we thought necessary in continental defence.”38

The Canadian government thus used the Mid-Canada Line to promote the idea that all three radar lines should be considered “an over-all continental defence warning system,” with Canada responsible for the construction and manning of one, the United States the other, with the third (the Pinetree Line) being a joint responsibility.39

DND photo

A DEW Line radome under construction.

Ottawa used the construction of the Mid-Canada Line to demonstrate that the DEW Line did not constitute an American takeover of the Arctic, but simply a section of a larger system that the United States had been assigned to build. That the US was responsible for this line in its entirety was, as Lester Pearson stated in the House of Commons, not an indication of any loss of control or of an abdication of sovereignty.

...[it was because] experience has shown that projects of this nature can be carried out most effectively by vesting responsibility for all phases of the work of construction and installation in a single authority. Accordingly it has been agreed that Canada would construct the mid-Canada warning line and the United States the distant early warning line.40

In building the Mid-Canada Line, rather than contributing to the DEW Line, Canada also avoided the embarrassment of being seen as a minor national partner. In the Far North, where the cost of construction was so much higher, every few million dollars Canada could contribute would be matched by tens of millions from the Americans.41 External Affairs felt that even a small contribution to the DEW Line would “merely serve to emphasize we were participating in the project but as a one-tenth partner.”42 The Canadian solution, to substitute participation in the DEW Line with the construction of the Mid-Canada Line, was meant to create the perception that Canada was an equal partner to the United States, as each had the responsibility for the construction of one segment of the system.

It was important for both the domestic Canadian and the international public to understand that the various radar lines constituted a single entity. External Affairs was adamant that “any announcements with regard to the distant early warning line should be drafted in such a way as to indicate that it was not an isolated project but part of an overall continental system.”43 Like the attempt to give the DEW Line a multilateral dimension, linking it to the Mid-Canada Line was an attempt to shape public perception. Regardless of what Canada did on the 55th Parallel, the American military still held de facto control over the Canadian Arctic. However, if the Canadian public and the international community perceived that American action in the context of a larger defence effort in which Canada was seen as pulling its own weight, the Canadian absence from the North seemed far less like an abdication and more like a delegation of responsibility.

After completion in 1957, the DEW Line remained in operation until 1985, when it was modernized and merged with a number of newly built stations to create the North Warning System. The fear of an American occupation of the North, and the loss of sovereignty that that would entail, never materialized. Following two seasons of construction, the majority of Americans involved left the area in 1957, and the provisions Canada had made to maintain its sovereignty proved effective. Indeed, contrary to the fears of the 1950s, the DEW Line turned out to be, in many ways, a valuable tool to Canadian sovereignty claims in the Arctic.

Those Sovereignty Provisions

Before allowing American construction to begin, the US government was required to agree to a long, detailed, and comprehensive set of conditions dictated by the Canadian government. These conditions were imposed to insure that American activity in the region would take place on Canadian terms. These terms covered every aspect of Northern activity, from the application of Canadian law and the use of radio frequencies and customs procedures to clauses concerning the provision of hunting licences and the protection of the local Inuit natives and the environment.44 Distinguished Canadian political scientist Doctor R.J. Sutherland believed that American acceptance of Canadian law and control in these areas constituted an implied recognition of Canadian sovereignty: “Canada received what the United States had up to that time assiduously endeavoured to avoid, namely, an explicit recognition of Canada’s claims to the exercise of sovereignty in the far North.”45 Regardless of whether the DEW Line brought this recognition, as Sutherland believes, or merely enforced it, as has been asserted by Doctor David Bercuson of the University of Calgary, the acceptance by the United States of the conditions demanded by the Canadian government represented a vital form of recognition on the part of the US government.46

As early as 1959, Canada was able to take over operational command of the Line, although manning and administration remained a predominantly USAF concern, and by 1968, most of the stations had become the responsibility of the RCAF. Once under Canadian control, the DEW Line provided much of what Canada needed most in the Arctic, namely, a physical presence. The enormous airstrips, constructed to handle USAF heavy lift aircraft, were a boon to both military and civilian agencies. These runways provided Canada access to many areas of the Arctic that had previously been limited by geography.47 The local stations provided communication and operations facilities where none had previously existed. They became bases for Arctic research missions, for search and rescue operations, for commercial exploration, and, of course, the sites continued in their primary role as surveillance centres. During the 28 years it remained in operation, the DEW Line wielded a major, positive, impact upon Canadian Arctic sovereignty. By making the region more accessible, and thus easier to control effectively, it allowed Canada to exercise a degree of physical control over its sovereignty that previously had not been possible.48

Map by Monica Muller

The eventual defensive upgrade to the system. The long-range radars of the NORAD North Warning System (NWS), circa 1985.

Conclusion

The DEW Line was the most ambitious project ever undertaken in the Canadian Arctic to that point in time. Over 460,000 tonnes of equipment and supplies were shipped north from Canada and the United States, including enough gravel to build two copies of the Great Pyramid of Giza, and it was all constructed in “...darkness, blizzards and sub-zero cold.”49 A long history of indifference towards its Arctic territory had left the Canadian government with little infrastructure, military presence, industry, or physical control in the North. The sudden infusion of men and material brought on by the construction and manning of 63 radar installations thus had the potential to fundamentally upset the image of Canadian control over what was essentially terra nullius, a vast expanse of unpopulated and unguarded ‘No-Man’s Land.’ Canada, lacking the ability to pay for the DEW Line itself, and, given the circumstances of the day, being unable to reject the American proposal, focused its energy towards maintaining the image of Canadian control over the project, and over the Arctic in general. All this was done to avoid giving the domestic and international community the impression that Canada had lost control over its Arctic, thus highlighting the tenuity of its claims to sovereignty. The battle Ottawa waged was not to gain control over the DEW Line, nor was it to ensure that the United States respected Canadian sovereignty while its citizens were in the region. Both of these conditions were assumed from the start and agreed upon in the exchange of notes that established the Line.50 Instead, Canada fought to maintain the perception of Canadian control in the Arctic. Ultimately, the notion of Canadian sovereignty over the region was maintained, and even enhanced. The DEW Line served to augment the Canadian position in the Arctic by providing what had always been lacking, a degree of physical presence and control.

![]()

Adam Lajeunesse is an MA student in History, currently studying Arctic sovereignty and security at the University of Calgary. His thesis examines Canadian-American relations in the Canadian Arctic throughout the Cold War period.

Notes

- Lynden T. Harris, The DEW Line Chronicles, at <http://www.lswilson.ca/ dewhist-a.htm>.

- Kim R. Nossal, The Patterns of World Politics (Scarborough, Ontario: Prentice Hall Allyn and Bacon Canada, 1998), p. 214.

- Dan Philpott, “Sovereignty,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, at <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sovereignty/#1>.

- Ibid.

- A carbon copy of the American B-29, the Tu-34 Bull had a range of roughly 5300 kilometres. Joseph T Jockel, No Boundaries Upstairs (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1987), p. 31. While most missions in the Bull would be one-way due to range limitations, the Tu-95 Bear had an effective range of 12,550 kilometres. Robert Jackson (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Aircraft (London: Amber Books, 2004), p. 490.

- R.J Sutherland, “The Strategic Significance of the Canadian Arctic,” in R. St. J. Macdonald (ed.), The Arctic Frontier (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), p. 264.

- Shelagh Grant, Sovereignty or Security? (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1988), p. 211.

- Telegram Claxton to Heeney, 25 September 1953, in Jockel, p. 81.

- Brian Cuthbertson, Canadian Military Independence in the Age of the Superpowers (Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1977), p. 70 [Italics added]

- H.L. Keenleyside speaking to Thomas Tynan, “Canadian – American Relations in the Arctic: The Effect of Environmental Influences upon Territorial Claims,” in The Review of Politics, Vol. 41, No. 3 (1979), p. 411. The American military was not always as sensitive as its government, and that was the cause of some tension during the war.

- Grant, p. 315, Note 31.

- In a memorandum to Cabinet, the Department of External Affairs estimated that each radar station would need a permanent staff of 200 men. Comparatively, Resolute, with the largest population in the Arctic Archipelago, had only 35 Canadians on site. Alert and Eureka had seven between them. Canada: Department of External Affairs, Documents: Memorandum: Prospective New Developments in the Arctic, 21 January 1953, Vol. 19, No. 694, p. 1050.

- Lexium, Canado-American Treaties: Exchange of Notes (5 May 1955) between Canada and the United States of America Governing the Establishment of a Distant Early Warning System in Canadian Territory, at <http://www.lexum.umontreal.ca/ca_us/en/cts.1955.08. en.html>.

- M.H. Wershof, Documents on Canadian External Relations: Memorandum by Defence Liaison (1) Division, 1 October 1952, Vol. 18, No. 690, p. 1123.

- Ibid.

- United States Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, Memorandum by Office in Charge of Commonwealth Affairs (Peterson), Western Europe and Canada; 1952-1954, 19 November 1952, Vol. 10, p. 2057.

- Nothing demonstrates this insecurity better than the move to name what are today the Queen Elizabeth Islands. In 1954, there was a fear that to inform the United States through regular channels of the renaming of the islands “might be constituted as an argument in support of an assertion of sovereignty, rather than merely an administrative act.” In an attempt at international nonchalance, it was agreed upon to simply slip the name change into the next communiqué to Washington. Elizabeth B. Elliot-Meisel, Arctic Diplomacy (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1998), p. 90.

- This was a pattern that extended to all Canada-US defence projects: In the final agreement governing the construction of the Pinetree radar line, a line was added stating: “The United States would consider its contributions to the project as measures of self-defence and not mutual aid to Canada. The division of costs was based on the relative importance of each station to the air defence of each country.” Documents on Canadian External Relations: Extract from Cabinet Conclusions: Defence Program; Report from the Cabinet Defence Committee, 24 January 1951, Vol. 17, No. 651.

- R.J. Philips, Documents on Canadian External Relations, Extract for Attachment to Memorandum from Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs to Secretary of State for External Affairs, 19 January 1952, Vol. 18, No. 743, p. 1195.

- Ibid., p.1194.

- Jockel, p. 45.

- Canada: House of Commons, Debates, (1959), Vol. 11, p. 1518.

- According to the Annual Report of 1959 tabled in Parliament, the Force had 145 members in the Northwest Territories, and 52 members in the Yukon. This includes regular police forces and is not limited to officers on the DEW Line.

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Draft Report: Canadian Participation in the Distant Early Warning Line, 21 December 1954, Vol. 20, No. 499, p. 1065. [Italics added]

- Thule being an American airbase in Western Greenland. Documents on Canadian External Relations: Policy Guidance Paper: Public Information on the North, 28 May 1954, Vol. 20, No. 509, p. 1139. – Canada would not take over control of most of the stations until 1968.

- Foreign Relations of the United States. Memorandum of a Canada-US Conversation, Western Europe and Canada 1955-1957; 8 March, 1955, Vol. 27, p. 852.

- The suggestion was that a NATO command, consisting of the US, Canada, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, and perhaps Britain, should operate the DEW Line. Jon McLin, Canada’s Changing Defence Policy, 1957-1963 (Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1967), p. 54.

- United States Department of State, American Foreign Policy 1950-1955: Cooperative Arrangements for Defence – the Pinetree Line: Joint Statement by the United States and Canadian Governments, 9 April 1954, No. 40, p. 1427.

- George R. Pearkes, Report on National Defence: 1959 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printers, 1959).

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Extract from Cabinet Conclusions, 22 January 1953, Vol. 19, No. 695, p. 1051.

- Ibid.

- Debates (1953), Vol. 15, p. 3541; Documents on Canadian External Relations: Draft Memorandum for Secretary of State for External Affairs to Cabinet, 21 January 1953, Vol. 19, No. 694.

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Memorandum from Chairman, Panel on Economic Aspects of Defence Questions, to Cabinet Defence Committee: Annual NATO Review, 22 November 1954, Vol. 20.

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Extract from Minutes of Meeting of Cabinet Defence Committee, 12 November 1954, Vol. 20, No. 482, p. 1044, Note 482, and Record of Cabinet Defence Committee Decision: Item III Experimental Project “Countercharge,” Vol. 19, No. 689, p. 1058.

- Harris.

- Benjamin Rogers, Documents on Canadian External Relations: Memorandum from Head Defence Liaison (1) Division, to Assistant Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs, 5 November 1954, Vol. 20, No. 479, p. 1031.

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Extract from Minutes of Meeting of Cabinet Defence Committee, 12 November 1954, Vol. 20, No. 482, p. 1043.

- Brooke Claxton, Documents on Canadian External Relations: Letter from the Minister for Defence to the Prime Minister, 21 October, 1953, Vol. 19, No. 718, pp. 1092-1093.

- Memorandum for Minister – Continental Defence: Distant Early Warning Line, November 17 1954, Canada U.S. Radar Defence System – Distant Early Warning File (File 50210-C-40 Part 2), Vol. 5926, Series A-3-b, RG 25, Library and Archives of Canada, p. 1. In Alexander W.G. Herd, “As Practicable: Canada-United States Continental Air Defense Cooperation, 1953-1954,” (MA thesis, Kansas State University, 2005), p. 80.

- Debates, (1955), Vol. IV, p. 3955.

- Herd, p. 51.

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Draft Report: Canadian Participation in the Distant Early Warning Line, 21 December 1954, Vol. 20, No. 499, p. 1066.

- Documents on Canadian External Relations: Extract from Minutes of Meeting of Cabinet Defence Committee, 12 November 1954, Vol. 20, No. 482, p. 1046.

- Lexium.

- Sutherland, pp. 270-271.

- David Bercuson, “Continental Defense and Arctic Sovereignty, 1945-50: Solving the Canadian Dilemma,” in Keith Neilson and Ronald G. Haycock (eds.) The Cold War and Defense (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1990).

- Herd, p. 87.

- Ibid, p. 88.

- Western Electric, The Dew Line Story, at <http://www.bellsystemmemorial.com/dewline.html>.

- Lexium.