This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

History

CWM 19710261-5376

In this evocative painting by George Pepper entitled Tanks Moving Up for the Breakthrough, the night advance conducted during the first phase of Operation Totalize is depicted.

Canadian Offensive Operations in Normandy Revisited

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Of all the climactic moments during the Second World War, the Normandy campaign of June to August 1944 remains one of the most popular in Western historiography. As historians have widely noted, the hard-fought victory of the Allies over Germany signalled the beginning of the final liberation of Western Europe, while simultaneously dashing whatever hopes the Germans may have still entertained regarding the war’s outcome. Historical and popular interest has caused almost every aspect of the campaign to be examined in considerable detail, of which the escape of the battered German armies from the Falaise pocket in the face of seemingly overwhelming Allied ground and air forces during August 1944 is the most notorious. In turn, the efforts among historians to ascertain the circumstances that permitted the Germans to escape have stirred controversies regarding the overall performance of Allied troops and commanders during the campaign’s various stages.1

Subsequently, much of the blame for the Allied failure in not destroying the German armies completely at Falaise has been unfairly placed upon the Canadian Army. Fighting along the eastern sector of the Allied bridgehead, it was the responsibility the First Canadian Army and the troops under its command to form the northern pincer lunging southward, while American forces, having broken through the German perimeter in the western sector, swung first east and then northwards.2 The Americans and Canadians would then meet somewhere between Argentan and Falaise, thereby trapping the bulk of the German forces, most of whom were still heavily engaged to the west of this area, in a large pocket. With most of their best troops in Western Europe subsequently destroyed, including all of their formidable panzer divisions, the Germans would be incapable of constructing another defence line strong enough to halt the Allied advance as it poured across France and into Germany. For their part in this operation, the Canadians undertook three successive offensives designed to punch a way quickly through the German defences: Operations Spring (25 July), Totalize (7-10 August) and Tractable (14-16 August).3 Each of these operations failed outright, or else failed to achieve its specified objectives within the assigned period, and all three have subsequently been highlighted by historians who have called into question the competency and ability of the Canadian Army during the campaign.

In terms of the post-war historiography, perhaps the most damning to the reputation of Canadian arms during the campaign were the comments made by historian C.P. Stacey in the official Canadian Army history, which are worth quoting here in their entirety:

It is not difficult to put one’s finger upon occasions in the Normandy campaign when Canadian formations failed to make the most of their opportunities. In particular, the capture of Falaise was long delayed, and it was necessary to mount not one but two set-piece operations for the purpose at a time when an early closing of the Falaise Gap would have inflicted most grievous harm upon the enemy and might even, conceivably, have enabled us to end the war sooner than was actually the case.4

Considering that Stacey was the historian who wrote the official account of the Canadian Army during the Second World War, his comments have been seized upon by many historians critical of the Canadian performance in Normandy.5 These have generally highlighted the failings of the Canadian soldiery during the campaign, while seemingly under-appreciating their accomplishments and the obstacles they faced. Indeed, much of this writing has seriously underestimated the actual strength of the German forces that opposed the Canadians, and the effect this had upon the outcome of their operations.6 The legacy of this historiography continues to be pervasive, although more recent scholarship has begun to reverse this trend.7

The following article will examine a commonly under-estimated obstacle facing the Canadian offensive operations in Normandy, namely that of the strength of the opposing German forces. While the strength and combat readiness of many German units had been degraded significantly by late July 1944, overall, the units facing the Canadians retained the greater proportion of their authorized establishments. Although much of the historiography of the Normandy campaign stresses the weakness of German forces by this point in the campaign, as will be seen, in fact this was generally far from the case. It is this fact that historians must keep in mind, especially when assessing the failure of Canadian offensive operations in Normandy.

German Disposition on the British Front

24–25 July 1944

Boundaries

xxxx |

Army |

xxx |

Corps |

xx |

Division |

III |

Regt |

German Units

- - 326th Inf Div

- - 276th Inf Div

- - 277th Inf Div

- - Pz Regt of 10th S.S. PZ Div

- Regt of 271st Inf Div

- 271st Eng BN - - 272nd Inf Div with elements of 2nd PZ Div and 9th & 10th S.S. PZ Div

- - 1st S.S. PZ Div

- - 12th S.S. PZ Div

- - 21st PZ Div (with remnants of 16th G.A.F. Div)

- - 346th Inf Div (with elements of 711th Inf Div)

- - 711th Inf Div (less some elements)

- - Pz Regt of 10th S.S. PZ Div

- Regt of 271st Inf Div

- 271st Eng BN - - 9th S.S. PZ Div (less some elements)

- - 116th PZ Div

- - 2nd PZ Div (less some elements)

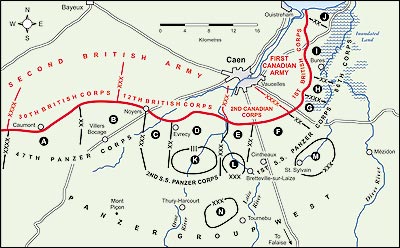

Map by Christopher Johnson

Map 1 – German Dispositions on the British Front 24-25 July 1944.

Verrières Ridge – Tilly-la-Campagne

25 July 1944

- - - - |

Canadian Front Line |

– – – – |

German Front Line |

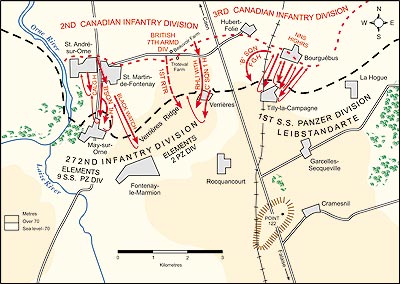

Map by Christopher Johnson

Map 2 – Verrières Ridge – Tilly-la-Campagne.

Operation Spring

Although Operation Spring has been labelled as a near-disaster by some historians, what generally has not been fully appreciated was that the attacking II Canadian Corps faced the most powerful German defence arrangement encountered by any of the Allied armies throughout the Normandy campaign. The strength of the positions held by the Germans during Operation Goodwood has long been referred to in explanations regarding that operation’s failure, since, along a front of approximately 13 kilometres, the attacking British and Canadians were faced by one panzer and two infantry divisions, with a further two panzer divisions in reserve.8 In contrast, during Operation Spring, the Canadian 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions of the II Canadian Corps attacked along a front of approximately seven kilometres, with the British 7th and Guards Armoured Divisions in reserve to exploit any breach in the German front. Opposite the Canadians, the Germans possessed one infantry and one panzer division in the frontline, while two panzer divisions were in reserve. Furthermore, within close proximity to the battlefield were two additional panzer divisions.9

This concentration of German resources resulted in an extraordinary defensive system. Along the front running between the Orne River at the village of St. Martin, to just west of Verrières, lay the 272nd Infantry Division. Although having been heavily involved in containing the Canadian advance south of Caen during Goodwood, this division was still largely intact and up to its authorized strength.10 Now assigned a narrow four-kilometre front, the division had at least two of its infantry battalions in divisional reserve, while the remainder of its units were deployed in-depth along its front.11 In addition to its organic artillery assets (amounting to four battalions), an artillery battalion of the 12th SS Panzer Division may have still been attached.

From Verrières to just east of the town of La Hogue was the 1st SS-Panzer Division. Four of its panzer-grenadier (motorized infantry) battalions held its front, which was reinforced by two panzer companies, two assault gun batteries, one pioneer company and one 88 mm battery of the divisional flak battalion.12 Furthermore, one reconnaissance company occupied an outpost position just south of Troteval Farm. Backing this formidable defence line, as immediate reserves, were the division’s remaining two panzer-grenadier battalions, together with the bulk of its panzer regiment, pioneer, reconnais-sance, and flak battalions.13 Although it had been involved in heavy combat since the end of June, the 1st SS-Panzer still retained the majority of its combat strength.14 Its operational armoured strength on 25 July was reported as 79 tanks and 32 assault guns, with a further 25 of both types in short-term repair.15 The division was weak in artillery, as one of its three artillery battalions remained in the division’s pre-invasion deployment area in Belgium, together with most of its Werfer (rocket-launcher) battalion.

Capable of reinforcing this already powerful line, the German I SS-Panzer Corps, to whom the above divisions were subordinate, possessed additional assets assigned as operational reserves. Behind the left wing of the 272nd Infantry, and concentrated between the villages of Laize and Bretteville, the 9th SS-Panzer Division was organized into two Kampfgruppen (battle-groups): one was built around the panzer regiment and a mechanized panzer-grenadier battalion,16 together with pioneer and flak companies, while the second contained the remaining three panzer-grenadier battalions and the divisional assault gun battalion. Supporting these units were the division’s artillery regiment and flak battalion.17 During late June and throughout July, the 9th SS-Panzer had suffered approximately 2000 casualties, most of which were riflemen, and, as a result, two panzer-grenadier battalions had been disbanded in order to reinforce the remainder. However, little equipment had been lost, which meant that the remaining units possessed a greater amount of firepower than they had previously enjoyed.18

In addition to the 9th SS-Panzer Division, a Kampfgruppe of the 2nd Panzer Division was located south of Rocquancourt astride the boundary of the 272nd Infantry and 1st SS-Panzer Divisions. This battle-group appears to have consisted of the division’s panzer regiment and two panzer-grenadier battalions, one of which was mechanized. The remainder of the 2nd Panzer Division was in the process of concentrating farther south around Tournebu. Having fought in Normandy since mid-June, this division was still in relatively good shape as it had previously held sector that had been comparatively quiet.19 The I SS-Panzer Corps also possessed strong support assets, as one heavy artillery battalion and the 7th Werfer Brigade were in the corps area on 25 July, together with the 101st Heavy SS-Panzer Battalion, which had 14 operational Tiger tanks on that date. Farther afield, other powerful German reserves were in the immediate vicinity of the Canadians’ projected advance route. The panzer regiment of the 10th SS-Panzer Division was in reserve west of the Orne as part of the adjoining II SS-Panzer Corps, while the 12th SS-Panzer Division (the other division of the I SS-Panzer Corps) also held a strong armoured group in reserve.20 Moreover, around St. Sylvain, in army group reserve was the completely fresh 116th Panzer Division.

Unit |

Panzers |

Assault Guns |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Immediately Available: |

Opera- tional |

In- Repair21 |

Opera- tional |

In- Repair |

Opera- tional |

In- Repair |

1 SS-PzDiv. |

79 |

22 |

32 |

3 |

111 |

25 |

2 PzDiv.22 |

60 |

? |

15 |

? |

75 |

? |

9 SS-PzDiv. |

44 |

? |

14 |

? |

58 |

? |

Totals |

183 |

22 |

61 |

3 |

244 |

25 |

Units Nearby: |

||||||

116 PzDiv. |

63 |

? |

25 |

? |

88 |

? |

10 SS-PzDiv. |

20 |

? |

11 |

? |

31 |

? |

12 SS-PzDiv. |

58 |

? |

– |

– |

58 |

? |

Total Nearby |

141 |

? |

36 |

? |

177 |

? |

Figure 1: German Armoured Strength during Operation Spring, 25 July 1944.

Against this formidable host, the six battalions that the II Canadian Corps initially committed to the operation were badly outmatched.23 The strong outposts of the 272nd Infantry Division, located in both St-André-sur-Orne and St-Martin-de-Fontenay, severely disrupted the Canadians’ subsequent advance, as these villages were to have marked the start line for the attack of the 2nd Canadian Division. The sole battalion assigned to clear these towns (the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada) was unable to do so before the battle ended, and then only with further reinforcements (Le Regiment de Maisonneuve).24 Although other units passed through to press the advance, the time required to clear the ground between the town of St-André and the first objective, May-sur-Orne, allowed the Germans to concentrate their resources for the defence of the latter. Subsequent attempts by the Calgary Highlanders to capture May failed, although some buildings on its northern outskirts were captured temporarily.

Farther east, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders attacked Tilly but were smothered by the intense defensive fire of the 1st SS-Panzer Division, which halted their advance and eventually forced them to retire after suffering heavy casualties. The only success for the Canadians occurred when the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry succeeded in overrunning the defenders of Verrières. However, the depth of the Germans defensive system, together with the immediate availability of strong panzer reserves, prevented the Canadians from exploiting what success they had achieved. When the Royal Regiment of Canada attempted to push past Verrières towards Rocquancourt, it was quickly halted by very heavy German fire, with one of its forward companies being virtually annihilated.25 Likewise, the Black Watch of Canada was nearly destroyed as it tried to advance into and through the German position north of Fontenay:

As the Black Watch advanced they came under heavy machine gun and sniper fire from the flanks, the front, even the rear. German tanks...rolled forward to shepherd them to their doom. Surrounded, they pushed on and died by the score.26

The reserve 9th SS and 2nd Panzer Divisions decisively ended Operation Spring during the afternoon of 25 July by launching strong counter-attacks that ejected the Canadians from their foothold in May, and which forced them to concentrate exclusively upon holding their tenuous positions around Verrières.27 With the committed battalions having suffered very heavy casualties, the II Canadian Corps was in no position to continue the fight.28 Considering the dispositions and firepower of the immediately available German forces, which totalled 19 infantry and six panzer battalions, compared with the forces the Canadians deployed, it is small wonder that Spring failed to achieve its broader goal of breaching the German front in preparation for a thrust towards Falaise.

Operation Totalize

Phase 2:8 – 10 August 1944

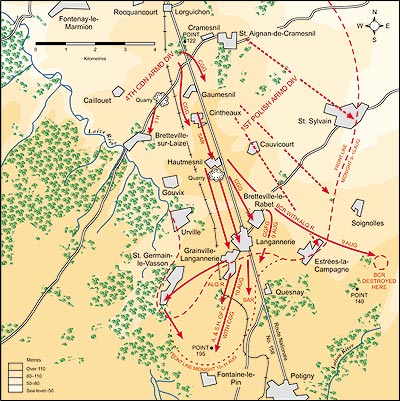

Map by Christopher Johnson

Map 3 – Operation Totalize.

Operation Totalize

Likewise, the strength of the German position during Operation Totalize has generally been under-appreciated by historians, since the traditional view that the Canadians, “despite overwhelming air and artillery superiority, five divisions and two armoured brigades comprising upwards of 600 tanks could not handle two depleted German divisions,” is not entirely accurate.29 In fact, during the period of 7-10 August, the II Canadian Corps encountered all or part of five divisions, together with powerful supporting units. The Canadians main adversary, the 89th Infantry Division, completed the relief of the 1st SS-Panzer Division on 6 August, and had time to firmly occupy the latter’s strongly prepared positions. Its two infantry regiments occupied approximately six kilometres of front, with four battalions in the first line and two in a second, while the divisional fusilier (reconnaissance) and pioneer battalions remained in reserve. With an authorized strength of 8500 men, the division had relatively weak support elements – three artillery battalions and a single anti-tank company.30 Nonetheless, at least one company of the 217th Sturmpanzer Battalion with 11 operational assault guns supported the division, as did at least one regiment of the 7th Werfer Brigade.31 An independent heavy artillery battalion was also in the I SS-Panzer Corps area.

During Operation Totalize, and especially on 8 August, the 89th Infantry Division generally gave a good account of itself.32 While the Allied armoured columns rapidly penetrated its positions during the night and then moved south, artillery, mortar and sniper fire added to the confusion of the Canadians and certainly slowed the forward progress of units pressing southward. Further hampering the Canadians was the fact that the German garrisons of bypassed towns and villages did not surrender, even though they found themselves surrounded in a torrent of advancing Allied troops. May-sur-Orne was not captured until 1630 hours, after two previous attacks by the Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal had been repulsed.33 Other troops of the 89th Division continued to hold Fontenay until ordered to withdraw south during the late afternoon of 8 August. Although the South Saskatchewan Regiment took Rocquancourt rather quickly, the last snipers were not flushed out of its ruins for another six hours. To the left of the Canadians, the British 51st Infantry Division was likewise unable to capture Tilly quickly. In fact, a full-scale assault during the morning of 9 August by two British infantry battalions, supported by armour and artillery, was necessary before the German garrison was finally overcome.34

While the Allied penetration forces during the initial break-in phase (Phase One) of the operation were able to seize their objectives quickly in the depth of the German position with only minor casualties, the continued German resistance in the above mentioned localities severely constricted the Allies’ advance routes. In turn, this produced traffic bottlenecks that slowed the movements of the exploitation units (Phase Two), notably the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, which reached its start line only shortly before the second stage of the operation was to commence.35 Although the 89th Infantry Division had suffered heavy losses on 8 August, most of its remnants withdrew southwards and by early the next day had reconstituted a front running along the Laize River to the town of Bretteville-le-Rabat. Other stragglers joined troops of the 12th SS-Panzer Division and the arriving 84th Infantry Division to continue the fight farther east.

Deployed along the left flank of the II Canadian Corps was the 272nd Infantry Division, which was still relatively strong and had one infantry regiment in tactical reserve.36 Once it became apparent that the positions of the 89th Division had been breached, this regiment was deployed quickly around the forest outside Secqueville. By the late afternoon of 8 August, this division had shifted additional units so that its front extended to St. Sylvain, which it held until late on 9 August. On the right flank of the attacking Canadians, across the Laize River, was the German 271st Infantry Division. Although having to deal with heavy British pressure from across the Orne, when Operation Totalize commenced the division slowly pulled back its front to conform to the advance of the Canadians. By the late evening of 8 August, one of its infantry regiments became available to create a new line running along the Laize River.37 In either case, the actions of the flanking German infantry divisions restrained the penetration made by the II Canadian Corps, and thereby contributed at least somewhat to its difficulties in moving forward the reserves, artillery, and supplies necessary for a rapid exploitation. More importantly, the speed with which these divisions reacted allowed the Germans to quickly re-create a continuous frontline.

The greatest opposition the Canadians faced during 8 August came from the 12th SS-Panzer Division, and, contrary to much of what has been written, it was still a potent force. Although having been forced to reduce three of its panzer-grenadier battalions to cadres, the remaining three still possessed between five and six hundred men apiece.38 The division’s artillery regiment and flak battalion were still largely intact, while, according to various sources, the division may have brought anywhere from 76 to 113 tanks and assault guns to the battlefield.39

At the time Totalize began, only one Kampfgruppe of the 12th SS-Panzer Division was in the immediate vicinity, mainly around the town of Brettville-sur-Laize.40 By early afternoon, units of this Kampfgruppe were already counter-attacking the 1st Polish Armoured Division just south of its departure line around St Aignan-de-Cramesnil, and effectively halted its advance in its tracks.41 Likewise, the rapid positioning of the 88 mm batteries of its flak battalion around Bretteville-le-Rabet, together with infantry outposts stationed in Cintheaux and Hautmesnil, prevented the 4th Canadian Armoured Division from rapidly advancing down the Caen-Falaise highway. Two additional Kampfgruppen, containing the remaining units of the division, arrived during the night of 8/9 August to bolster the German line further, and it was one of these that destroyed the British Columbia Regiment when the latter advanced southwards on 9 August.

Further significant German reinforcements quickly mate-rialized during the course of Operation Totalize to stem the Canadian offensive. During the afternoon of 9 August, elements of the fresh 85th Infantry Division began to arrive, and participated in the destruction of the British Columbia Regiment. By the next morning, a Kampfgruppe – consisting of one infantry regiment of three infantry battalions, one pioneer company, one anti-tank company and one artillery battalion – had entered the line, while the division fully completed its assembly two days later.42 The 102nd Heavy SS-Panzer Battalion also arrived on 9 August, as did a further company of the 217th Sturmpanzer Battalion. Elements of the III Flak Corps were also moved up to bar the Canadians advance during the afternoon of 8 August, although the extent of its participation in the battle remains something of a mystery.43

Operation Tractable

14–16 August 1944

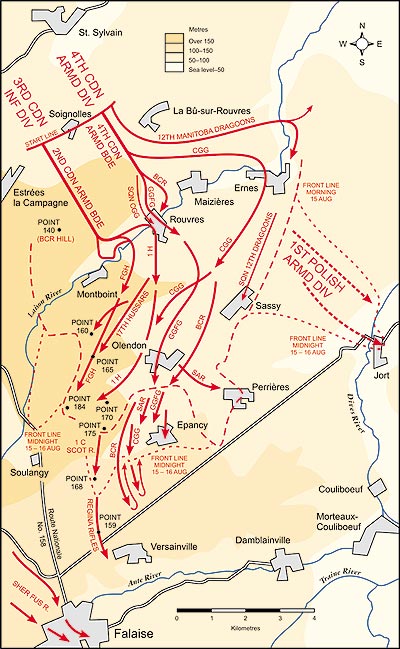

Map by Christopher Johnson

Map 4 – Operation Tractable.

Operation Tractable

After the conclusion of Totalize on 10 August, the German front facing the Canadians was certainly stretched to the breaking point and had lost much of its former cohesion. Nonetheless, during Operation Tractable (14-16 August), the Canadians still faced a formidable obstacle. Directly in the path of this new operation was the 85th Infantry Division. As noted above, it had arrived only recently.44 Occupying reverse-slope positions, its two infantry regiments were deployed north of the Laison River. More importantly, two infantry battalions, together with the division’s fusilier battalion and artillery regiment, were stationed south of the river, creating a strong in-depth front that appears to have been reinforced further by additional units of the III Flak Corps.45 To the division’s left, the 89th Infantry Division, although having been reduced to approximately half of its fighting strength, continued to occupy strong defensive positions centred upon a series of towns, woods and hills, as did the 272nd Division to the north-east. Together with all of the smaller miscellaneous units already mentioned above, backing up this line were the remains of the still dangerous 12th SS-Panzer Division, now organized into a series of small Kampfgruppen acting as close reserves and providing the infantry divisions with additional anti-tank support.46

Although the Canadians rapidly overran the 89th Division’s forward elements when Tractable commenced on 14 August, the German second position south of the Laison inflicted numerous casualties upon the Canadians as they sought to ford the river.47 While the Canadians secured their immediate objectives for the day, the depth of the German’ defensive system effectively slowed their advance over the course of the following days, and resulted in very fierce and costly fighting as the Canadians fought their way forward. Following the action along the Laison on 14 August, the 1st Hussars were reduced to 24 operational tanks,48 while in capturing Hill 168 on 15 August, the Canadian Scottish Regiment suffered its heaviest single-day casualties of the war, and described its experience as fighting in a “molten fire ball.”49 While the Germans were unable to stop the advance of the II Canadian Corps during Tractable, the casualties they inflicted reflect the level of resistance the Canadians continued to face.50

NAC PA111565

The ultimate outcome of the three aforementioned operations... Major David Currie (third from left with pistol drawn), supervises the surrender of German troops in St. Lambert-sur-Dives on 19 August 1944. It has often been said that this is the closest we are likely to get to a photograph of a soldier (Currie) actually winning the Victoria Cross.

Far from being as decimated or as weak as some sources have indicated, the German formations opposing the Canadians throughout their breakout efforts still retained a very considerable portion of their original strength, and in some cases were completely fresh. Any criticism of the inability of the Canadians, and especially of their armoured units, in not having achieved a greater advance during Totalize, for example, must be tempered by the reminder that by 9 August the Germans had deployed between 110 and 150 armoured vehicles to stop them.51 Furthermore, considering the resistance it offered on 8 August, the 89th Division was in fact not the weak formation it has been attributed to have been52, and that it, “stayed to fight, and very tough they proved.”53 Indeed, when considering all three Canadian offensives, it is clear that the opposing German forces were considerably stronger and more numerous than many accounts portray, and that they played an extremely significant, and perhaps decisive, role in shaping the outcome of these operations.

![]()

Gregory Liedtke is a military historian specializing in the German Army 1933-1945 and the Russo-German War of 1941-1945. He holds a Masters in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada and is currently enrolled in a PhD program there.

Notes

- For an excellent summary of the Allied performance in Normandy, in terms of the key issues and the corresponding debates within the historiography, see Stephen Powers “The Battle of Normandy: The Lingering Controversy,” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 56, No. 3 (July 1992), pp. 455-471.

- The exact intention, development, and objectives of much of the Allied planning following the landings in Normandy continues to be a matter of considerable debate. The specific plan relating to the encirclement of the German forces in the region between Falaise and Argentan only emerged during the first days of August as the Americans broke into Brittany and then turned eastward. The principal Allied plan, as it emerged in early July, involved breakout operations by both the Americans and British designed to destabilize and push back the German front, rather than effect an encirclement. Carlo D’Este, Decision in Normandy (New York: Harper Collins Pub., 1983.), pp. 331-334.

- Although not commonly associated with the Canadian efforts to break through to Falaise, I have included Operation Spring since it was, in fact, intended to achieve just that.

- C.P. Stacey, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III, The Victory Campaign- The Operations in North-West Europe, 1944-1945 (Ottawa: The Queens Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1960), pp. 275-276.

- To name but two works, see David J. Bercuson, Maple Leaf Against the Axis: Canada’s Second World War (Toronto: Stoddart Pub., 1995) and John English, The Canadian Army and the Normandy Campaign: A Study of Failure in High Command. (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Pub, 1991) and D’Este.

- Readers are referred to the comprehensive examination and appraisal of the German Army in Normandy, through the use of archival records, found in Niklas Zetterling, Normandy 1944: German Military Organization, Combat Power and Organizational Effectiveness (Winnipeg, Manitoba: J.J. Fedorowicz Pub., 2000).

- For more recent work on the Canadians in Normandy, see Terry Copp, Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003) and Ken Tout, The Bloody Battle for Tilly: Normandy 1944 (Stroud, United Kingdom: Sutton Pub, 2000). As an interesting side note, Tout goes so far as to state: ‘It was none other than C.P. Stacey, the official historian, who dug the knife into the wounds and twisted it. Others lined up behind Brutus with sharper knives.’ Tout, p. 234.

- D’Este, p. 377 and L.F. Ellis, Victory in the West: Volume One- The Battle of Normandy (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1962), pp. 332-333.

- See Map One for the disposition of German units.

- Although no exact casualty figures for this division have been found, there are references that suggest it had suffered approximately 1000 casualties during Operation Goodwood, with one of its battalions being reduced to two companies. However, it had arrived in Normandy with a total strength of 12,725 men, of which two-thirds were combat troops. This suggests that most of its infantry battalions were still in relatively good condition. Zetterling, pp. 252-254.

- According to the division’s history, the Germans noted the preparations for the offensive. Anticipating this as heralding another major effort by the Allies to break out of the eastern portion of the bridgehead, the division’s front was shortened to create an in-depth defensive position. Martin Jenner, Die 216./272. Niedersachsische Infanterie Division, 1939-1945 (Bad Nauheim: Podzun Verlag, 1964), p. 159.

- Most of the regimental support companies were also in the front line, further augmenting the volume of firepower the battalions in line could produce.

- Rudolf Lehmann and Ralf Tiemann, Die Leibstandarte, Band IV/1 (Osnabruck: Munin Verlag, 1986), pp. 182-183.

- The division may have brought approximately 16,000 of its personnel to Normandy by the time Spring was launched, although it had a ration strength of 21,262 men on 1 July. Between 1 June and 18 July, the division reported 1441 casualties. Zetterling, p. 307

- See Figure One for a summary of German armoured strength during Operation Spring.

- Mechanized panzer-grenadier battalions were fully equipped with half-tracked armoured vehicles (SPW); the remaining battalions possessed only trucks.

- The divisional pioneer and reconnaissance battalions remained under the command of the neighbouring II SS-Panzer Corps.

- Wilhelm Tieke, Im Feuersturm Letzter Kriegsjahre: II. SS-Panzerkorps mit 9. und 10. SS-Division “Hohenstaufen” und ‘Frundsberg” (Osnabruck: Munin Verlag, 1965), p. 183.

- With an original strength of 15,900 men, the 2nd Panzer Division suffered 1391 casualties during June and was only relieved by an infantry division until 21-23 July. On 11 August, even after it had participated in the Mortain counter- offensive, its panzer-grenadier regiments still possessed approximately 50 percent of their original strength. Zetterling, p. 314.

- The Kampfgruppe of the 12th SS-Panzer Division consisted of the division’s panzer regiment, one strong mechanized panzer-grenadier battalion, and one self-propelled artillery battalion.

- Refers to vehicles in short-term repair (i.e. repairable within two weeks)

- The exact strength of this division is unknown; the figures cited here, dated from 5 August, are only to provide a general idea regarding the division’s approximate armoured state. An incomplete listing for 25 July indicates that 13 Panther tanks were operational while 26 more were in short-term repair. Zetterling, p. 314.

- The remaining battalions were either kept in reserve, were responsible for manning sections of the frontline or else were too weak following previous battles to participate in the fighting.

- Terry Copp, The Brigade: The Fifth Canadian Infantry Brigade, 1939-194. (Stoney Creek: Fortress, 1992), p. 72.

- Michael Reynolds, Steel Inferno: I SS Panzer Corps in Normandy (Staplehurst: Spellmount, 1997), p. 195.

- David J. Bercuson, Battalion of Heroes: The Calgary Highlanders in World War II (Calgary: Calgary Highlanders Regimental Funds Foundation, 1994), p. 77.

- Michael Reynolds, Sons of the Reich: History of the II SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, Arnhem, the Ardennes and on the Eastern Front (Havertown, Pennsylvania: Casemate, 2002), p. 56. For an excellent account of the German actions during the battle, see Roman Jarymowycz, “Der Gegenangriff vor Verrières: German Counterattacks during Operation ‘Spring’, 25-26 July 1944.” Canadian Military History Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring 1993), pp. 75-89.

- Of the attacking battalions, the North Novas suffered 139 casualties, the Black Watch 307, the Calgary Highlanders 177, and the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry 210. Total Canadian losses on 25 July amounted to approximately 1500 casualties, including 450 dead. Reynolds, Steel Inferno, pp. 193-196.

- English, p. 289.

- Zetterling, p. 237.

- There may also have been a second company of the 217th Sturmpanzer Battalion present. The location of the other regiment of the 7th Werfer Brigade cannot be fully ascertained, although it is thought to have been within the I SS-Panzer Corps area. Ibid, p. 185.

- This is in contrast with most references that cite this division as being of poor quality, mainly because of the comments made by the commander of the 12th SS-Panzer Division that he had to rally fleeing members of the division personally. Tout has only praise for the men of the 89th Division, writing: “Many hundreds of them waited in slits and ditches, behind hedges and walls, out in the featureless countryside, along the poplar lined road, among the houses and down the mine shafts, green troops anxious to prove their mettle in their first show.” Tout, p. 197.

- During the third attack that eventually captured the village, the four companies of the regiment were reduced to 150 combatants. Ibid, p. 185.

- Terry Copp, Fields of Fire, p. 202.

- Reginald Roy, 1944: The Canadians in Normandy (Canada: Macmillan of Canada, 1984), p. 191 and Stacey, p. 223.

- In early August, this division received some 600 replacements and a number of anti-tank guns from the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, which had been disbanded following its near destruction during Operation Goodwood. Zetterling, p. 254. During “Totalize” this division may have also received support from the 9th Werfer Brigade and two heavy anti-tank artillery battalions.

- By 9 August, one company of the 217th Sturmpanzer Battalion and elements of the 102nd Heavy SS-Panzer Battalion joined the division to defend this sector. It eventually took the Canadian 2nd Division from 11-14 August to clear this area and secure II Corps flank. Stacey, p. 236.

- The riflemen of the disbanded battalions were absorbed into the remaining units, together with a limited number of replacements.

- These numbers are from Zetterling, pp. 178 and 361, and Reynolds, Steel Inferno, pp. 230 and 238, respectively. The difference between the two may be that Zetterling perhaps gives the number of vehicles possessed by the first battle-group to reach the battlefield, since his figures do not indicate whether they reflect the whole or only a part of the division.

- This force consisted of one panzer and one panzer-grenadier battalion, together with the division’s artillery regiment, anti-tank, and flak battalions.

- The Poles lost approximately 40 tanks, while the British lost 20. Reynolds, Steel Inferno, p. 237.

- Zetterling, p. 236.

- Although many histories make a reference to the importance of the III Flak Corps, the actual regiments, as a whole, do not appear to have become involved in ground combat during Operation Totalize. The Corps did possess flak combat groups (Flak Kampfgruppen) specifically created to deal with armoured breakthroughs and these were equipped with eight 88 mm flak guns each. According to the available sources, at least one, and possibly two, were dispatched to reinforce the German line during the night of 8/9 August, while one or two of the regular flak battalions were probably engaged against Canadian armour on 8 August. Stacey, p. 224. However, it is questionable if the III Flak Corps played such a significant role in the German ground defence of Normandy as many history books have stated previously, since the unit’s own records claim that only 92 tanks were destroyed during the campaign, of which 12 were destroyed by hand-held anti-tank weapons. Horst-Adalbert Koch, Flak – Die Geschichte der Deutschen Flakartillerie und der Einsatz der Luftwaffenhelfer (Bad Nauheim: Podzun Verlag, 1965), p. 141 and see Zetterling, pp. 152-157.

- Its authorized strength was 8725 men and 14 heavy anti-tank guns. One of its artillery battalions may have still been equipped with 8.8 cm anti-tank guns. Zetterling, p. 235.

- The capture by the Germans of a copy of the Canadian operation order was the probable cause for them to organize their defences in this way. Stacey, p. 238.

- By this point, the 12th SS Division still retained between 34 and 42 operational tanks and assault guns, and may have still had about 1000 riflemen in its panzer-grenadier battalions. Reynolds, Steel Inferno, p. 251. The two Tiger battalions still possessed 48 tanks, but perhaps as few as 13 were operational when “Tractable” commenced. Egon Kleine and Volkmar Kuhn, Tiger: The History of a Legendary Weapon (Winnipeg: J.J. Fedorowicz, 2004), pp. 260 & 331.

- According to one account from the Fort Garry Horse, “the whole area was stiff with 88 mm, 75 mm and 50 mm anti-tank guns...unfortunately our loss in tanks were severe and the dreadful sight of tanks going up in flames was common...” John Marteinson and Michael McNorgan, The Royal Canadian Armoured Corps: An Illustrated History (Kitchener, Ontario: The Royal Canadian Armoured Corps Association, 2000), p. 277.

- Michael McNorgan, The Gallant Hussars: A History of the 1st Hussar Regiment, 1856-2004 (Aylmer, Ontario: The 1st Hussars Cavalry Fund, 2004), p. 181.

- Copp, Fields of Fire, p. 231. The regiment suffered 37 killed and 93 wounded. Stacey, p. 249.

- Throughout the Normandy campaign, the Canadians suffered 18,444 casualties, of which 7415 occurred between 1-23 August. When the losses of Operation Spring are included, the casualties incurred during the period associated with the Canadians breakout attempts amount to nearly 50 percent of their total losses. Stacey, p. 271.

- These figures reflect the total number of armoured vehicles the Germans could have previously had or have brought to the area in which Totalize occurred. Again, the differences between the two numbers reflect the discrepancies between the information provided by Reynolds in Steel Inferno, and by Zetterling.

- Copp, The Brigade, p. 98.

- Tout, p. 213. This contrasts with the popular image, produced in some German accounts, that the 89th Division fled wholesale. See Hubert Meyer, Kriegsgeschichte der 12. SS-Panzerdivision “Hitlerjugend” (Osnabruck: Munin Verlag, 1982), p. 302.