This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Review Essay

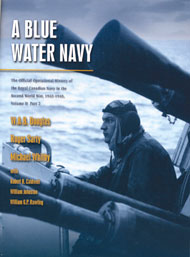

A Blue Water Navy: The Official Operational History Of The Royal Canadian Navy In The Second World War – 1943-1945, Volume II, Part 2

by W.A.B. Douglas, Roger Sarty and Michael Whitby, with Robert H. Caldwell, William Johnston and William G.P. Rawling

St Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell, 2007

ISBN 1-55125-069-1

650 + xvii pages, $60.00 (hardcover)

Reviewed by Doctor Richard H. Gimblett

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Finally, 62 years after the end of the Second World War, the concluding official chapter on the part played by the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) in that global struggle has appeared. That it has been awaited anxiously is something of an understatement, especially in comparison to the official records of the other services, both of which have been available for some time. Perhaps the wartime RCAF historical section had been a little quick off the mark with its four-part The R.C.A.F. Overseas published between 1944 and 1949. However, that initial treatment was followed up with the landmark Directorate of History studies, The Creation of a National Air Force in 1986 (covering the interwar years and home front activities) and The Crucible of War in 1994 (covering the wartime overseas operations). Certainly the official Army stories laid down in six volumes throughout the 1950s by Colonels Charles Stacey and G.W.L. Nicholson have stood the test of time. Even if they have not proven to be “the final word,” military historians continue to use them as the launching point, for example, for the Normandy Campaign debates reviewed from time to time in these pages.

Finally, 62 years after the end of the Second World War, the concluding official chapter on the part played by the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) in that global struggle has appeared. That it has been awaited anxiously is something of an understatement, especially in comparison to the official records of the other services, both of which have been available for some time. Perhaps the wartime RCAF historical section had been a little quick off the mark with its four-part The R.C.A.F. Overseas published between 1944 and 1949. However, that initial treatment was followed up with the landmark Directorate of History studies, The Creation of a National Air Force in 1986 (covering the interwar years and home front activities) and The Crucible of War in 1994 (covering the wartime overseas operations). Certainly the official Army stories laid down in six volumes throughout the 1950s by Colonels Charles Stacey and G.W.L. Nicholson have stood the test of time. Even if they have not proven to be “the final word,” military historians continue to use them as the launching point, for example, for the Normandy Campaign debates reviewed from time to time in these pages.

By either of these standards, the senior service stands out as something of a laggard. Strictly speaking, it was Defence Minister Brooke Claxton who ordered the termination of the RCN’s official history in 1947. The gist of this story is covered very nicely in Tim Cook’s Clio’s Warriors, reviewed in the Spring 2007 edition of the Canadian Military Journal. But whereas the General Staff found a way to continue Stacey’s work, the Naval Staff was just as happy that their wartime problems being uncovered by Gilbert Tucker and James George were not exposed as fodder for public parliamentary debate. They settled quite happily instead for Far Distant Ships, a popular account by journalist Joseph Schull, who had served during the war as a naval information officer. In fairness to Schull, this reviewer strongly recommends Far Distant Ships as the best introductory single-volume read on the RCN in the Second World War, but it skirts some difficult issues, is wrong on others, and should not be confused as a definitive historical record.

Good things, however, come to those who wait. Although A Blue Water Navy is credited to three principal and three secondary authors, this volume, in truth, is the product of a much larger team at the Directorate of History and Heritage, and it has profited over the past three decades from a body of scholarship encompassing practically every practising naval historian in Canada, and many abroad, especially from the United Kingdom, from the United States, and from Germany. The ‘Select Bibliography’ of historical narratives and secondary works speaks for itself on this point. (Full disclosure to those reading these words – although cited in the Bibliography and identified in the Acknowledgements, my period of expertise does not cover the Second World War, and my role was one of after-the-fact proofreading, so I declare no conflict of interest in undertaking this review.) Regrettably, not all of those involved have survived to celebrate the gestation – one poignant example is Bill Constable, the cartographer for this and many of the modern DHH publications, who died suddenly three days after attending the official 1 May 2007 launch in National Defence Headquarters. More importantly, too many veterans are no longer with us to bask in the reflected glow on their valiant efforts.

This is not a stereotypical official history, in that it is not a succession of facts and events. Neither is it clouded by sensitivity to the reputations of senior commanders and politicians (none of whom are with us any longer), nor was its research overly constrained by limited access to historical records. Indeed, an argument can be made that this volume (along with its Part 1 sister, No Higher Purpose, 1939-1943) stands as the fullest and most honest account of any nation’s armed forces from that period. As just one example, this is the only allied history that is able to acknowledge openly the role of ULTRA intelligence in shaping operations. Others, such as those by the Royal Navy’s Steven Roskill and the United States Navy’s Samuel E. Morison, obviously were informed by some knowledge of “special intelligence” but not authorized to disclose it, and, therefore, had to be careful in the language of their analysis and the sweep of their conclusions. In that vein, since its first disclosure in the early 1970s, many academic as well as popular accounts have included ULTRA in their analyses, but A Blue Water Navy again distinguishes itself by a measured and balanced appreciation that comes with the passage of time, in this instance to conclude that even ULTRA was not as crucial a factor in winning the war as proclaimed in the first blush of revelation.

The volume is replete with similarly new interpretations on a whole range of subjects. Students of the wartime RCN obviously will read it with great interest, if only for correcting the prevailing consensus that the RCN was absent from the critical convoy battles of April and May 1943 that turned the tide against the German U-boat offensive, conclusively demonstrating (Page 39) that “...[Canadian] groups escorted thirteen of the thirty-five North Atlantic convoys that sailed from both sides of the ocean during those two months.”

However, A Blue Water Navy deserves also the close inspection of present members of all three services, as well as from the broader community of defence analysts, simply because it is difficult to identify a recent work of historical scholarship of more relevance to the present-day defence condition. The following list is far from comprehensive, but it gives an inkling of the modern concerns that might benefit from an understanding of how our predecessors handled alarmingly parallel issues: the delicate American/British/Canadian negotiations that led to the establishment of the Canadian Northwest Atlantic as the only theatre of war under command of a Canadian officer (Rear-Admiral Leonard Murray); the rapid development of a robust amphibious capability in recovering from the disaster of Dieppe to move on to crucial roles in each of the invasions of North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy, amongst others; the closely related challenges of inshore anti-submarine warfare while operating under constant threat of enemy surface and air forces; the sacking of Chief of the Naval Staff Vice-Admiral Percy Nelles for blatantly political reasons by Minister Angus L. Macdonald; the split in Cabinet and within the bureaucracy over the structure of the postwar fleet; and the very nature of sea power as the fundamental enabler of the western maritime alliance that emerged victorious from the six-year struggle.

A Blue Water Navy concludes the story begun in No Higher Purpose, of how Canada earned its place as a charter member of that western maritime alliance – how an essentially coastal defence navy, that in 1939 consisted of only a ‘baker’s dozen’ of ships and fewer than 2000 sailors by the summer of 1945 had swelled to nearly 100,000 men and women all ranks, had proven instrumental in the defeat of Nazi Germany and was preparing to operate two carrier task forces in support of the invasion of Imperial Japan. It is a remarkable story, impressively told.

![]()

Richard Gimblett, a former naval officer, is Command Historian of the Canadian Navy.