This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

History

CMJ collection

Flanders Poppies

The Development of Infantry Doctrine in the Canadian Expeditionary Force: 1914-1918

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

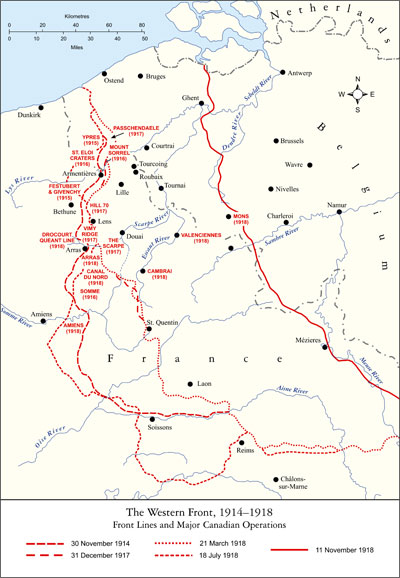

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) has been called the ‘shock army’ of the British Empire, and, throughout the First World War, it produced several stunning victories, such as those at Vimy Ridge and Amiens, as well as during the pursuit to Mons. Yet, in 1914, the embryonic elements of the CEF were poorly trained and equipped, and they were largely amateurish in their approach to war fighting. The battalions of the first contingent to sail to Europe consisted mostly of partially trained militiamen who were only slightly removed from civilians with respect to their degree of expertise and professionalism. The vast majority of the officers who commanded the CEF during its formative years owed their positions not to their own merit or skill at commanding soldiers in battle, but, rather, to their political connections.

How then, was this poorly led, trained, and equipped force capable of delivering the “Miracle of Vimy,” or of breaking the back of the German Army at Amiens and at Drocourt-Quéant less than four years later? This article will attempt to contribute to the understanding of that transformation by examining the development of one specific branch within the CEF, namely, the infantry. The CEF was mainly an infantry force and the development and resultant success of the Canadian Corps relied to a large degree upon the perfection of infantry tactics. While others have written about the contribution of artillery, machine guns, and tanks to the Canadian victories of the First World War, considerably less study has been devoted to this largest and most decisive branch of the CEF.

The innovative use of artillery and tanks certainly played a role in the defeat of the German Army, but both were tools designed to assist the infantry, and not the decisive branches themselves. Therefore, it is important to study the development of infantry doctrine in the CEF in an effort to better explain its successes. This article will therefore examine the development of Canadian infantry from 1914 to 1918, with an emphasis upon the changes in tactics, organization, training, and equipment used and developed throughout that period. The focus here is on the lower levels of command within the CEF, specifically the battalion level and below, as that is the level at which the greatest changes were made. A chronological approach has been used to track the progress of the Infantry Corps, and, as such, this article has been divided into three sections covering the periods 1914-1916, 1916-1917, and 1917-1918.

CWM 197 10261-0061

Throwing Grenades, painting by Lieutenant Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien.

1914-1916 – From Inception to the Somme

The Infantry Corps of the Militia, Canada’s army prior to the First World War, was the largest branch of that force. It was organized, much as it is today, based upon regionally recruited regiments employing volunteer soldiers on a part-time basis. Regiments varied in size and quality, although training and equipment throughout the Militia were of a uniformly low standard at the turn of the 20th Century. Units were largely administrative in nature and they were seen more as pools of potential manpower for a levée en masse, rather than formed fighting units.1 As such, training was sporadic at best, and standards for officers and soldiers were not high.

However, beginning in 1898 under the British General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Canadian Militia, General E.T.H. Hutton, changes had been initiated with a view to creating “...a balanced force of all arms with the necessary administrative services, sufficiently well trained and equipped to make a worthwhile contribution in an emergency.”2 Despite this stated goal, General Hutton and subsequent Chiefs of the General Staff (CGS) in Ottawa battled political interference and chronic under funding. The infantry of the Militia did benefit from more and better training conducted by British regulars, and later by the Permanent Force of the Militia itself, but standards remained low. Officers in particular were frequently unqualified to hold their ranks, and efforts to improve their level of training met with only limited success.3

Considerable resistance was encountered from the government, which was loath to spend more than absolutely necessary on defence, and who were also unwilling to relinquish control of officer appointments within the Militia. Politicians had long appointed supporters as militia officers as a form of patronage, so increasing training standards meant that merit rather than connections would be the sole qualifier for commissioning. This problem was exacerbated after 1911 by the appointment of Sam Hughes as Minister of the Militia. Hughes openly despised the Permanent Force, and saw little value in the proposals made by the various CGSs. In short, he was a firm believer in the strength of the mass army of citizen soldiers over the long-serving professional army.

Despite these obstacles, the Militia, and therefore the Infantry Corps, did improve in the years before the First World War. In the decade preceding the war, the number of militia soldiers undergoing training increased from 36,000 to 55,000,4 and the quality of both the leadership and the training in general was slowly improving. In 1908, the Militia fielded its largest training concentration to that date, and this was accompanied by some improvements in equipment and organization. The Imperial Conference of 1909 urged the Dominions to align their organization, equipment, and training with that of the British Regular Army in an effort to ensure commonality and to allow for the employment of Dominion forces alongside the Home Armies in future conflicts.5 Progress was being made and, as the distinguished Canadian historian Jack Granatstein states, in 1914, “[w]hile still a relatively unready nation, Canada was infinitely better prepared for war than at any previous time in its history.”6

As with many other aspects, the Militia borrowed its infantry doctrine almost completely from the British Army. That doctrine, while recently evolved to embrace the ‘open order revolution’ and skirmisher tactics,7 was still very linear in nature. Infantry was seen as the decisive arm, and the soldier armed with a long-range rifle and a bayonet was viewed as the essence of that arm. Battalions defeated their enemy through weight of aimed rifle fire, or by engaging in close quarters combat with bayonets. As described in the manual Infantry Training, 1914: “The object of fire in the attack, whether of artillery, machine guns, or infantry, is to bring such a superiority of fire to bear on the enemy as to make the advance to close quarters possible.”8 Both the offence and the defence were based upon a linear layout of firing, support and reserve lines, with an emphasis upon frontal attacks. The British Army was the last major army to adopt the platoon organization, and its tactics were still very much based upon the use of companies as the lowest manoeuvre element. Sections under the command of sergeants did exist – not as independent elements, but, rather, solely for the control of fire. Infantrymen were generalists in that they were all expected to know how to shoot, dig, march, and fight with their bayonet. Battalions could be described fairly as a homogeneous mass of riflemen having very little in the way of fire support. Finally, the British Army placed much less emphasis upon the use of machine guns than did other armies. They were seen as merely augmenting rifle fire, rather than adding a new capability to battalions.9 This doctrine was to form the basis upon which the CEF was formed and trained in 1914.

When war broke out in August 1914, Sam Hughes scrapped the mobilization plan drawn up at Militia Headquarters and set out to create the 1st Canadian Division from scratch. The infantry battalions that were formed ad hoc in the new camp at Valcartier were modelled upon their British counterparts, although they retained an eight-company organization rather than the new four- company variant. Each battalion received two Colt machine guns, and the soldiers were equipped with the Ross rifle and inferior Canadian webbing, shovels, and boots. This substandard equipment was to hinder Canadian infantrymen throughout the early years of the war, until it was all gradually replaced by more suitable British equipment.

Training at Valcartier was similarly less than ideal, as a shortage of space and constant reor-ganizations made it difficult for battalions to get past more than the most elementary of training. Marksmanship and physical fitness were emphasized, but little time was available for advanced or collective training.10 Compounding this problem was a lack of qualified instructors, and the fact that approximately one-third of the officers of the 1st Division were not qualified to hold their positions. Furthermore, the training of the soldiers in the infantry battalions varied widely, with some having previous service in the British Army, and others having no experience or training whatsoever.11

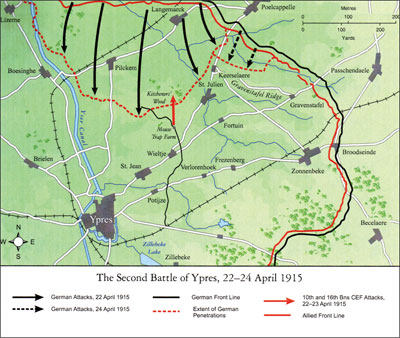

This situation improved greatly when 1st Division sailed to the UK and encamped on Salisbury Plain. Once there, and despite the mud and wet weather, the division was able to conduct collective training, and to build upon the individual training that had commenced at Valcartier. In addition, at this time, the infantry battalions converted from an eight-company to a four-company organization, and, by early 1915, the division was more or less trained and organized as a standard British infantry division. In February 1915, it crossed the Channel and joined the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the area of Armentières, and was subsequently declared combat ready following an inspection by the Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, Field Marshal Sir John French.12 The division did not have to wait long to see its first major action, in the Ypres salient, in April 1915. There, it was responsible for holding a stretch of the front line 4500 yards long located to the northeast of the town of Ypres itself.

On April 22nd, the German 26th Reserve Corps attacked the French units on the Canadians’ left flank behind a cloud of chlorine gas. This was the first use of chemical weapons on the Western front. The battalions on the division’s left became embroiled in the battle, and reserves were brought forward to seal the division’s now wide-open flank. In an attempt to restore the situation, several Canadian battalions counterattacked, but these attacks were hastily planned and poorly supported by artillery, and almost all were disastrous failures. The infantry battalions attacked in accordance with the doctrine of the day, with “...six waves of men marching shoulder to shoulder on a two company front...”13 The attacking infantry dutifully rushed the German defences and cleared out the trenches with bayonets, “...the favourite weapon of the mass psychology school of tactics.”14 This parade-ground format resulted in horrific casualties, and little progress against even a disorganized and exhausted opponent. Canadian infantry had learned their first harsh lesson about modern warfare, and undoubtedly had realized that they would have to adapt if they were to be successful.

One tactic the Canadians developed early on in an effort to master this new form of warfare was the trench raid.15 Trench raids were intricately planned and rehearsed attacks by specially equipped infantrymen with the aim of capturing prisoners, gaining intelligence, destroying enemy fortifications, or encouraging the enemy to commit his reserves. The Canadian infantry battalions soon became experts at trench raids, which allowed them to dominate ‘no man’s land’ in between the opposing forces. The real benefit to trench raids came from the experience it gave infantry battalions, and even brigades, in the planning and execution of complex operations.

In the months following the battle at Ypres, the 1st Canadian Division was involved in an inconclusive battle at Festubert, and a more productive one at the town of Givenchy. Although not terribly successful, the attack on Givenchy was to serve “...as a model for successful major engagements fought later by the Canadian Corps.”16 The attack included the infantry being supported by an intricate artillery bombardment, including the use of a few artillery pieces in the direct fire role. Furthermore, the infantry battalions employed grenades to clear the German trenches and machine guns to support their advance, and to cover the consolidation of any gains realized. This indicated a decreased reliance upon the bayonet as the close quarters weapon of choice, and an increased understanding of the benefits of the machine gun as a support weapon. Nonetheless, while the tactics of the infantry battalions involved in the attack did not differ greatly from those employed at Ypres, the coordinated use of support weapons and detailed planning prior to the attack did foreshadow the greater changes that were to take place within all branches of the CEF.

The next major engagement fought by the newly formed Canadian Corps was that of the St. Eloi craters in April 1916. During this battle, the 2nd Canadian Division replaced a British division in the middle of a battle for six large craters that had been detonated underneath the German lines. The 2nd Division was given a very difficult task and ultimately failed to capture the craters, but the result of this battle was a desire within the corps to examine and improve tactics at all levels.

In June 1916, the Canadian Corps was on the defensive in the area of Mount Sorrel. Although initially pushed back, the corps did not repeat the mistakes of Ypres. Rather than throwing waves of infantry at the enemy in unsupported counterattacks, the 1st Division mounted a planned and coordinated attack, supported by copious amounts of artillery. The attack was very successful, and it demonstrated to the Canadians once again the value of supported deliberate attacks.

This lesson was again reinforced when the Canadians became involved in the massive Somme Offensive during August. In September, the corps took part in the successful attack on Courcelette, where many innovations were trialled for the first time – including the tank and the creeping barrage. Both were to prove helpful to the attacking infantry, although the tank’s mechanical unreliability and the still-limited effectiveness of the artillery against entrenched soldiers diminished their contributions. Rather than relying upon the leading wave to capture the final objectives, as had been doctrine in past battles, the infantry at Courcelette advanced by ‘bounds,’ whereby successive waves of soldiers captured ever-distant objectives.17 This tactic served two purposes: it allowed battalions and brigades to focus on limited objectives, and it preserved the momentum of the attack by continuously pushing fresh troops forward. The use of ‘bounds’ by the infantry is indicative of the growing disenchantment with the concept of ‘artillery conquers, infantry occupies’ that had been the basis of British (and therefore Canadian) doctrine prior to the Somme Offensive.18 Commanders and staffs had begun to realize that artillery was not conquering, and, therefore, the infantry would have to adopt a more deliberate technique for eliminating German positions.

Throughout the remainder of September and through November, the Canadian Corps undertook a number of limited attacks in the area of Courcelette that met with some success, although more frequently with defeat. As with earlier battles, the artillery was not fully able to defeat the German defenders or to breach the barbed wire in No Man’s Land, and the infantry suffered heavy casualties while conducting rigid linear attacks.

CWM 19710261-0093

Canadian Gunners in the Mud – Passchendaele, 1917, by Lieutenant Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien.

The organization and equipment of Canadian infantry battalions changed more than did the tactics of those units between 1914 and 1916. A growing number of machine guns assigned to infantry units was the principal impetus driving many of the organizational changes. When the 1st Canadian Division entered the trenches in 1915, the British decided to double the number of heavy Colt machine guns per battalion from two to four. By February 1916, the Colts were replaced by the lighter, and therefore more mobile, Lewis machine guns on a ‘one for one’ basis. The arrival of Lewis guns meant that the infantry could now easily bring the firepower of their machine guns along with them on the attack, thereby providing much needed support during a consolidation on newly captured ground.19

In addition to increasing the number of machine guns, the infantry also adopted a new weapon and placed increasing emphasis upon an old one. The new weapon was the rifle grenade, which was a standard hand grenade attached to a stick that was inserted into the barrel of a rifle, and then launched by firing a blank round from that rifle. Rifle grenades gave the infantry its own short-range artillery, allowing for the suppression of enemy machine gun positions during an assault. This weapon went a long way to restoring the ability of the infantry to manoeuvre in the face of machine gun fire, and the Canadian Corps readily adopted it.

The hand grenade, on the other hand, was a much older weapon, but it was also one that had fallen into disuse in the years before the First World War. It was quickly brought back into service, with soldiers initially improvising their own hand grenades, until the arrival of the Mills bomb in early 1916.20 This weapon became very popular because of its utility and efficiency in clearing out trenches, machine gun positions, and dugouts. As mentioned earlier, the grenade quickly replaced the bayonet as the preferred weapon in close quarter battle.

By the conclusion of the Somme Offensive, the infantry battalions of the Canadian Corps had seen considerable action and had learned some difficult lessons with respect to trench warfare. The Canadian infantryman had become an expert at the trench raid, and had begun to transform from the pre-war rifleman/ generalist into a more highly trained specialist. They were employed as machine gunners, rifle grenadiers, bombers, or snipers, and they were beginning to rely more on the firepower of support weapons, rather than the rifle and bayonet.

However, despite these changes, the organization of infantry companies and platoons changed little. Similarly, tactics remained linear, with battalions advancing steadily in waves. The infantry did not yet practise fire and manoeuvre but rather fire or manoeuvre,21 and this reflected the continued, albeit diminishing, belief in the concept of ‘artillery conquers, infantry occupies.’ Prior to the Somme Offensive, senior British officers believed that the unsuccessful attacks of the first two years of the war were the result of insufficient or ineffective artillery, rather than deficient infantry tactics.22 Following the costly battles of the Somme, the Canadian Corps began to consider more substantial changes to infantry doctrine in order to improve that branch’s effectiveness and to reduce casualties.

1917-1918 – Vimy and Passchendaele

Following the Somme, the Canadian Corps experienced a relatively quiet winter in the trenches. During this period, the lessons of the previous two years were reviewed, and many changes were made to infantry tactics and organizations. General Sir Julian Byng, who had assumed command of the corps prior to the Somme Offensive, was an innovator who sought to greatly improve the manner in which attacks were conducted. To this end, in January 1917 he ordered Major General Arthur Currie, then commander of the 1st Division, to visit the French forces that had fought at Verdun in order to learn from their successes. Among Currie’s conclusions from these visits was the need for improvements in the tactics and organization of infantry platoons. More specifically, Currie had noted how the French had developed platoons capable of independent manoeuvre with distinct sections of machine gunners, rifle-grenadiers, bombers, and riflemen. Unlike Canadian platoons that were still relatively homogenous in comparison, the French platoons were capable of supporting their own advance with integral support weapons organized into specialist sections.

General Currie was also deeply impressed with the quantity and quality of training that French troops conducted prior to an attack. He became convinced that a key to success in operations was thorough training and rehearsals by all ranks.23 However, neither the French platoon organization nor the emphasis upon training were entirely foreign to Canadian infantrymen. As noted earlier, the Canadian Corps had begun to adopt many of the weapons in use by the French, and this had necessitated a degree of specialist training, although it had not yet resulted in a reorganization of the platoon. Similarly, the Canadians had become masters of the trench raid, an operation that required meticulous training, rehearsals, and preparations. Where the French approach to infantry attacks was viewed as revolutionary by Canadians was in the use of fire and manoeuvre at the platoon level.

The Canadian Corps had continued the gradual improvement of the infantry after the Somme, but under Byng, and with the recommendations of Currie, more dramatic changes took place in early 1917. At the height of the Somme Offensive, infantry battalions had been augmented with a total of 12 machine guns – two per company and four in the battalion machine gun sections. Immediately after the Somme, this number was increased to 16, so that each platoon in the battalion would possess its own dedicated Lewis gun.24 More fundamental changes were made to the organization of the platoon itself, and specialist sections were formed, based upon the French model. Platoons now consisted of one Lewis gun section, one bomber section, and two rifle sections.25

Changes in organization were not only limited to the platoons, as brigades and divisions underwent remodelling. Following the staggering casualties of the Somme, the British had decided to reduce the size of their infantry divisions by three battalions each, in order to maintain the strength of the remaining nine battalions. The Canadian Corps did not emulate this example, as it was not faced with a manpower shortage. Rather than reduce the number of battalions in a division, Currie decided to increase the establishment of each of the twelve battalions in the divisions by 100 men.26 Similarly, the divisions and brigades of the corps were bolstered with additional heavy weapons, making them the most powerful formations of their size in the British Expeditionary Force. Divisions now had a very large machine gun battalion with 96 Vickers heavy machine guns27 and eventually each division would boast one heavy, two medium, and three light trench mortar batteries.28 The result of these additions was that “...a Canadian division was vastly more potent than a British division...”29 and began to resemble a British corps in terms of its infantry strength and firepower.

CWM 19710261-0067

Scottish Canadians in the Dust, Vimy, painting by Lieutenant Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien.

Tactics used in both the attack and the defence evolved, based upon French as well as British and even German influences. Rather than the inflexible and linear attacks of the preceding years, the Canadian infantry adopted formations that were more complex and put a much greater emphasis upon fire and manoeuvre and flanking attacks, right down to the platoon level. During the advance, bat-talions no longer arrayed themselves into firing, support, and reserve lines, but, rather, into more specialized assault, mopping-up, and consolidation groupings. Assault groups would destroy machine gun positions and would be armed mostly with rifle grenades and Lewis guns. Mopping-up parties would then follow with a preponderance of hand grenades to clear dugouts and bypassed trenches. Finally, a supporting group would follow with heavier weapons, such as Vickers machine guns and trench mortars, as well as barbed wire and sandbags to allow for the immediate consolidation of any gains achieved.

As with the attack, the defensive tactics of the Canadian Corps evolved from a linear system based on forward, support, and reserve trench lines, to a new ‘blob’ system. This style of defence relied upon the establishment of mutually supporting strong points, or ‘blobs,’ with the ground between each strongpoint being swept by machine gun fire. The strong points were sited upon important terrain features, were protected by wire, and were capable of ‘all-round defence,’ meaning they could continue to resist if attacked from the flank, or even from the rear.30 However, as it materialized, the Canadian Corps did not have the opportunity to test developments in defensive doctrine seriously, as it was on the offensive for most of the last two years of the war.

At the platoon level, the new tactics stressed the use of fire, combined with manoeuvre, to neutralize German strong points. Based upon the new organization, platoons would simultaneously suppress a strongpoint, and then assault it from a flank. Normally, the Lewis gun section would pin and distract the enemy while bombers and riflemen worked their way around a flank to a position where they could close with and destroy the strongpoint and its defenders with hand grenades and bayonets.31 The use of flank attacks and fire and manoeuvre was not limited to platoons, as companies and battalions practised similar tactics for the reduction of larger or more complex strong points. These new tactics were a clear departure from those used in 1914, and they were to be the cornerstone for much of the success of the Canadian Corps during the last two years of the war.

The spectacularly successful assault on Vimy Ridge in April 1917 is often showcased as an example of the doctrine of ‘artillery conquers and infantry occupies.’ While it is true that the elaborate and crushing artillery bombardment did contribute greatly to the victory, it alone was not responsible for the corps’ success. The changes to infantry tactics and organization, implemented by Byng and championed by Currie, combined with the painstaking rehearsals and training conducted by the assaulting troops, played a larger role than is often attributed. Artillery barrages are never capable of destroying every enemy machine gun or strongpoint, and in previous battles, single machine guns had held up the advance of entire battalions, even after intense and prolonged bombardment. Where the infantry at Vimy differed was in their method of dealing with the survivors of the bombardment. Whereas before 1917, platoons had neither the equipment, organization, nor tactics to deal with such strong points, at Vimy they were much better suited for what they encountered. As a result, the assaulting infantry were not held up by lone German machine guns, but, rather, they were able to quickly destroy those they could, or bypass those they could not, leaving them for later destruction by mopping-up parties. Sir Arthur Currie attributed much of the credit for the successes of the corps in 1917 and 1918 to these changes in tactics and organization.32

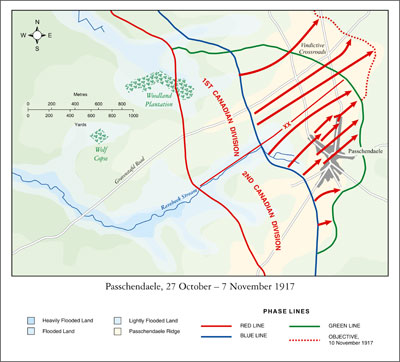

Following the victory at Vimy Ridge, the Canadian Corps conducted two more successful operations, at Hill 70 in August, and at Passchendaele in October and November 1917. In both battles, the new infantry tactics bore fruit as the corps captured its objectives, despite considerable resistance and nearly impassable battlefields. The attacks employed the same formula as had been developed for Vimy, with the infantry battalions manoeuvring in bounds in concert with an elaborate artillery fire plan. The successes, however, were not as spectacular as Vimy, and at Passchendaele, the infantry suffered horrendous casualties. Nonetheless, the infantrymen of the corps had proven themselves to be among the very best soldiers on the Western Front, and they had gained a well-deserved reputation for toughness and innovation.

In the short time from the end of the battles of the Somme to the successful capture of Passchendaele, the infantry of the Canadian Corps had undergone a dramatic, even revolutionary transformation. The infantryman had evolved fully from a generalist into a specialist trained in the use of one of many support weapons now at the disposal of a platoon. More importantly, however, these specialists were grouped into sections with specific roles. This was a necessary condition for the adoption of fire and manoeuvre at the platoon level, with one section suppressing the enemy while the others attacked the enemy’s flank. Fire and manoeuvre was a dramatic departure from the doctrine of 1914 that called for massed, linear waves of riflemen desperately trying to advance against entrenched machine guns. Now, the Canadian infantry had both the tools and the tactics necessary to attack and defeat such objectives.

1918 – Amiens and the Last 100 Days

The lessons of Passchendaele encouraged further development of infantry doctrine in both the British and Canadian divisions. During the spring of 1918, a second Lewis gun was added to each platoon, raising the number of machine guns to 32 in each battalion. Platoons were reorganized once again with two Lewis gun sections and two rifle sections grouped into two equal half-platoons. This modification allowed for the conduct of fire and manoeuvre below the platoon level, as each half-platoon was now capable of simultaneously suppressing and assaulting an enemy position.33

The infantry also continued with the development of more flexible and effective tactics. The conduct of movement during the attack and the formation adopted by attacking forces was further refined to allow for greater independence at all levels. Sections now advanced in rushes and were more dispersed across the battlefield in order to reduce casualties from artillery and machine gun fire. With this greater independence came the need for considerable initiative and leadership at the NCO and junior officer levels. As Canadian infantry officer and historian Shane Schreiber describes it: “Gone were the days when waves of infantry charged into a hail of machine gun fire, replaced instead with carefully planned, short, sharp dashes under the cover of vicious close-range supporting fire.”34

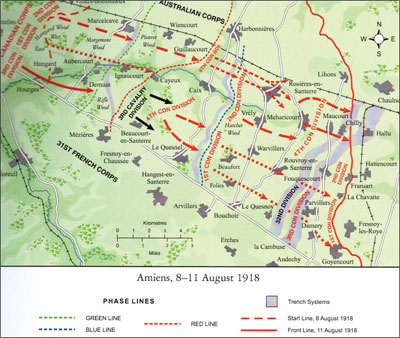

As with the lower level tactics, the tactics and formations of battalions and brigades also evolved. During the attack on Amiens in August 1918, the brigades advanced as they had at Vimy and Passchendaele, with an assault group, mopping-up group, and a consolidation/support group. However, one addition to this formation was groups of ‘skirmishers’ leading each battalion. These skirmishers served as scouts, detecting enemy positions and then guiding the assault wave and accompanying tanks onto those positions.35 Once involved in a fight, infantry from half-platoon up to brigade-sized formations employed the principles of fire and manoeuvre to outflank and destroy enemy positions. During the battle for Amiens, and later in September during the formidable confrontation at the Drocourt-Quéant Line, the infantry applied these complex and difficult tactics with great success. Most accounts of individual engagements fought during those battles by platoons, companies, and battalions describe the resounding triumph of the new tactics in dealing with German defences.36

During the battles of 1918, the infantry of the Canadian Corps was very much integrated into a combined arms team, and they seldom operated alone. Co-operation with tanks, artillery, cavalry, machine guns, mortars, engineers, and aircraft served to greatly augment the efforts of the infantry. Training throughout the spring and early summer of 1918 had focused upon the destruction of strong points by the combined efforts of infantry, artillery, machine guns, tanks, mortars, and engineers. The corps also trained extensively in mobile warfare, with the infantry emphasizing route marches, as well as hasty attacks, and the rapid establishment of defensive positions. Mobile warfare called for very close cooperation between the infantry and supporting arms, and many of the techniques employed by the Canadian Corps would be refined further and employed by the German Army in the Second World War. By these means, the corps was able to strike with a force greater than that possessed by its individual elements. However, despite the increased emphasis upon combined operations, the infantry very much remained the decisive arm of the corps.

Conclusion

The Canadian Corps had become expert at assaulting and cracking the most difficult defences by the time of the battles of Amiens and the Drocourt-Quéant Line. Much of this success can be attributed directly to the improvement of infantry doctrine throughout the preceding four years. The application of fire and manoeuvre down to the platoon level, combined with more flexible formations and combined arms tactics, enabled the infantry of the Canadian Corps to achieve spectacular successes by the end of the war. The infantry that fought during the last 100 days of the Great War would have been almost unrecognizable to the infantryman of 1914. In that year, the soldiers of an infantry battalion were almost exclusively generalists, armed only with a rifle and a bayonet. Tactics were linear and highly formulaic, and they tended towards frontal attacks and mass bayonet charges. There was no understanding of the benefit of fire and manoeuvre, and independent attacks made by platoons and sections were unthinkable.

By the end of the war, the necessities of trench warfare and the horrendous casualties of Ypres and the Somme had forced the development of more advanced infantry doctrine. As historians John English and Bruce Gudmundsson explain: “...by the end of the Great War... the infantry consisted of two types of troops – those who served machine guns and those who specialized in destroying them.”37 The adoption of greater quantities and types of weapons at the platoon level was indicative of the transformation of that organization into a ‘machine gun destroyer platoon.’ Lewis guns, rifle grenades, and hand grenades were all adopted to allow the infantry to first suppress and then to destroy enemy machine gun nests. The adoption of more flexible and effective tactics and formations similarly allowed the infantry to destroy machine guns with comparative ease and fewer casualties. While it was only one element of the Canadian Corps, the infantry was by far the decisive branch in that formation. Therefore, the success of the corps very much relied upon the effectiveness of its infantry battalions. By 1918, the infantry had developed into a very efficient, potent, fighting force, and this transformation contributed greatly to the successes of 1917 – and ultimate victory in 1918.

![]()

Major Haynes, an infantry officer who has recently served as an advisor with the Strategic Advisory Team – Afghanistan in Kabul, is currently a company commander with the Royal Canadian Regiment in Petawawa. This article was based upon part of his research towards a Masters in War Studies degree at the Royal Military College of Canada.

Notes

- Stephen J. Harris, Canadian Brass: The Making of a Professional Army 1860-1939 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), pp.11-13.

- Colonel G.W.L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1962), p. 7.

- Harris, pp. 23-26.

- Nicholson, p. 7.

- United Kingdom, General Staff, War Office, Field Service Pocket Book 1913 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1913), p. 227.

- J.L. Granatstein, Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), p. 55.

- John A. English and Bruce I. Gudmundsson, On Infantry, Revised Edition (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1994), pp. 1, 7.

- United Kingdom, General Staff, War Office, Infantry Training (4-Company Organization) 1914 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1914), p. 134.

- English and Gudmundsson, p. 8.

- Nicholson, pp. 24-25.

- Ibid., p. 24.

- Ibid., p. 49.

- Ibid., p. 66.

- English and Gudmundsson, p. 23.

- There exists some debate as to which army actually conducted the first trench raid during the First World War. Bill Rawling gives a good summary of the development of the raid in Surviving Trench Warfare: Technology and the Canadian Corps, 1914-1918 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), p. 47. However, Jack Granatstein gives the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) credit for ‘inventing’ the trench raid in Canada’s Army, p. 82.

- Nicholson, p. 105.

- Ibid., 168.

- English and Gudmundsson, p. 23.

- Rawling, pp. 58-59.

- Ibid., pp. 57-58.

- Nicholson, p. 176.

- English and Gudmundsson, p. 24.

- Rawling, pp. 90-91.

- Ibid., pp. 72, 82.

- Ibid., pp. 92-93.

- Nicholson, p. 232.

- Rawling, p. 178.

- General Staff, G.H.Q., Order of Battle of the British Armies in France (Including Lines of Communication Units) and Order of Battle of the Portuguese Expeditionary Force (London: Imperial War Museum, 1989), pp. 66-67.

- Granatstein, p. 129.

- English and Gudmundsson, pp. 27-28.

- Rawling, p. 123.

- Ibid., p. 134.

- Ibid., p. 175.

- Shane B. Schreiber, Shock Army of the British Empire: The Canadian Corps in the Last 199 Days of the Great War (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1997), p. 27.

- Ibid., p. 47.

- Daniel G. Dancocks, Spearhead to Victory: Canada and the Great War (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1987), pp. 44, 51, 67.

- English and Gudmundsson, p. 15.