This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

History

CWM 19710261-0316

Canadian Outside the Depot – Siberia, Russia, painting by Colonel Louis Keene.

Forgotten Battlefields – Canadians in Siberia 1918-1919

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Unbeknownst to most Canadians, our fighting men in the First World War actually saw action in Russia in 1918, and continued fighting into most of 1919. In fact, during the Siberian intervention portion of this campaign, the British commander was a Canadian, Brigadier-General James H. Elmsley. However, the choice of going to Russia was not one that Canadians made independently, but, rather, it was a decision made by the strategic leaders in Britain, France, the United States, and Japan. Canada had an operational voice, but had little strategic influence, until the very end.

Background

The Allies did not decide to intervene in Russia as an independent operation divorced from other strategic considerations. The decision to intervene grew out of what was considered a ‘necessity’ following a series of strategic stumbling blocks experienced by the Western Allies in 1917. For the Allies, 1917 became a year of both crisis and pessimism. That year, Germany, as head of the Central Powers, came closest to military victory.

A series of bloody events had led to continuous setbacks for the Allies throughout the year. The first Russian Revolution, occurring in March, overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, but only established an ineffective government that allowed the Russian army to begin its disintegration. The takeover of the Russian Provisional Government by Alexander Kerensky accelerated the disintegration of the Eastern Front throughout the spring and summer of 1917.

At the same time, the Allies were plagued by failed offensives and stalemates along the Western Front, and in Italy. The Chemin des Dames offensive, initiated by the French, with British support, was expected to achieve a breakthrough, but it resulted in only a few hundred yards of gained territory. Although it resulted in the Canadian Corps emerging victorious and proud with a solid reputation for combat excellence on Vimy Ridge, the offensive bogged down to a stalemate after a week, and it eventually resulted in the mutiny of the French Army. The 1917 summer assault at Ypres, known as the Battle of Passchendaele, also held aspirations for a breakthrough to the Belgian coast. However, this offensive quickly became a ‘slogging match’ that ground to a halt in November 1917 after the Canadians captured the village of Passchendaele. The Italian Front fared no better, resulting in the complete rout of the Italian Army through the combined Austro-German offensive at Caporetto.

The Eastern Front constituted an even worse fiasco. The Russians had launched an offensive against the Austro-Hungarian forces at the beginning of July. Although initially successful, the Russian advance was stopped by the middle of the month, and was then forced back, deep into Russia, throughout the rest of the summer. The Russian Army broke and ran, initiating anarchy throughout the Russian Empire, resulting in the successful Bolshevik Revolution of November. This, in turn, caused the new Russian Soviet government, led by Lenin, to conclude a separate peace with the Central Powers. The result was the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed by the Russian Bolshevik Government and the Central Powers, led by Germany. The failure of the Russian Army then forced the Allies to consider their options for continuing the fighting on the Eastern Front.

Anarchy and civil war raged throughout Russia, with various factions gaining nominal control in different areas of the vast empire. At the same time, Germany continued to press eastwards, threatening to capture vast quantities of Allied materiel, stockpiled at Archangel and Murmansk in the north and at Vladivostok in the east. The advance into south Russia also threatened to give the Germans control of the Russian ‘breadbasket,’ thereby gaining access to food and raw materials desperately needed by Germany to continue the war.

Military intervention on the part of the Allies appeared to be a necessity to counteract the German advance. Yet, antipathy between the United States and Japan prevented the formation of an Allied policy on action in Russia. More than half a year of negotiations occurred before a decision on military intervention was achieved. It was not until August 1918 that the political leadership in Japan, France, the United States, and Britain finally agreed that combined military intervention in Siberia was required. However, even before all parties had agreed, Britain sought troops for these actions. On 10 July 1918, the War Cabinet discussed what British forces were available for immediate deployment to Vladivostok to maintain order.1 The Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), General Sir Henry Wilson, informed the Ministers that a battalion at Hong Kong was available for deployment to Siberia at short notice. The War Cabinet decided that the CIGS should take immediate action to move the battalion to Siberia, and that Arthur Balfour, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, should telegraph Lord Reading, the British Ambassador in Washington, with instructions to inform the Americans what action was being taken and why it was being generated. At the War Cabinet meeting the next day, the CIGS reported that he had issued the orders to commence the transfer.2

Canada Gets Involved

At a later War Cabinet meeting, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, noted a request to Canada for troops to deploy to Siberia. The intent to ask Canada for a Siberian contingent was made specific in a telegram to Lord Reading, for discussion with Ottawa.3 This request occurred at the same time the War Office asked the Canadian Overseas Ministry in London for Canadian troops to take part in another Russian intervention in the North.4 Finding sufficient manpower remained the most difficult aspect for making the intervention a success.

The request for Canadian aid in Russia did not come as a surprise to Sir Robert Borden, the Canadian Prime Minister, since the problems of the Eastern Front and the reluctance of President Woodrow Wilson to participate therein had been items of discussion at the Imperial War Cabinet when it had begun its most recent discussions in June 1918. Upon Borden’s arrival in London, his close friend, Leopold Amery, a member of the Secretary of War’s personal staff, had delivered a copy of Major-General Alfred Knox’s evaluation of the necessity for intervention.5 Knox had been military attaché in Russia until after the Bolshevik Revolution. In the memorandum, Knox stated that intervention in the Far East was the only way of ending the war in 1919.6 Asking for Canadian participation was a normal extension of both the Cabinet discussions and Knox’s assessment, although it could not be considered a foregone conclusion that Canada would participate.

Borden continued to be an outspoken critic of the way the British high command was running the war.7 In that vein, he was an ally of Lloyd George in his battle with Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and the War Office senior staff.8 Although not recorded in his memoirs in detail, Borden notes that talks on Siberia and Russia did occur in Cabinet. On 24 June 1918, the Imperial War Cabinet discussed Lloyd George’s interview with Alexander Kerensky, the deposed president of the Russian Provisional Government. The British Prime Minister reported that Kerensky believed that Russia was “...ripe to take up arms again against Germany,” and that it would be ready to accept intervention. Japanese intervention would also be considered acceptable, if it was presented as part of the overall Allied effort to help Russia. Borden then noted that Kerensky’s opinion reiterated the need “...[for] Allied intervention and not Japanese intervention.”9 Borden went even further at the Imperial Cabinet meeting two days later. In the discussions with respect to the conditions that the Japanese had set down for their participation in the Siberian intervention, Sir Robert stated “...that our real object was to endeavour to induce the anti-German elements in Russia to unite in opposing Germany. It was quite clear that they could not make any headway without Allied intervention.”10 From these statements, it can be deduced that Borden supported Allied intervention. Further evidence of his support was demonstrated in correspondence with Sir Edward Kemp, the Canadian Overseas Minister. These letters showed that Borden supported a Russian intervention, and thus backed Lloyd George against Haig and his insistence upon sending every available soldier to the Western Front.

David Lloyd George’s recording of a request to Canada for troops for the Siberian intervention in the War Cabinet Minutes of 18 July 1918 was an acknowledgement of a War Office request made a few days earlier. It was also an action that gave substance to a musing the British Prime Minister had made in a secret War Cabinet meeting in May. At that meeting, Lloyd George had suggested that since the Americans appeared loath to intervene in Siberia, perhaps Canadian troops could substitute for them.11 As to the War Office appeal, Major-General Sir Percy de B. Radcliffe, Director of Military Operations (DMO) at the War Office, had asked for a Canadian contingent in Siberia before the Americans had agreed formally to participate in the intervention.

CWM 19710261-0328

American, Japanese, French, and British sailors at Vladivostok. They were part of the larger Allied intervention force operating against the Bolsheviks.

On 9 July 1918, the DMO wrote to W. Newton Rowell, the President of the Canadian Privy Council in Borden’s Government, who was then in England after touring the Western Front. Radcliffe asked Rowell to approach the Canadian Prime Minister with a request for troops. Major-General Bridges, the British military representative in Washington, had discussed the possibility of Canada supplying troops for a Siberian expedition with Canadian government ministers and the Canadian General Staff during the previous week in Ottawa.12 On 12 July, Major-General S. C. Mewburn, the Canadian Minister of Militia, wrote to Borden, confirming his verbal report of his meeting at the War Office on the same day, and enclosing a formal request from the British for Canadian troops to take part in the Siberian Intervention.13 The formal request detailed the need for a full brigade with headquarters staff, medical support, artillery, and service support. It also asked that the expedition be kept secret at the request of Balfour, since negotiations were still in progress with the other Allies.14

On the same day as Mewburn’s letter to Borden, the Militia Minister telegraphed Major-General W. G. Gwatkin, the Canadian Chief of the General Staff, to have the Canadian Militia Council start to organize the Canadian contingent, and to attempt manning the brigade with volunteers. The Minister noted that the British battalion being sent from Hong Kong to Vladivostok would be incorporated into the Canadian contingent, and that the overall commander would be a Canadian. Mewburn also asked that specific individuals for the position of the Canadian brigade commander be considered.15

While the Canadian Militia Headquarters prepared to create the Siberian contingent, President Wilson agreed to American participation. He proposed a force of 14,000 troops, half American, and half Japanese. The British considered the numbers to be totally inadequate, but believed the first priority was to get the expedition initiated, and then to augment participation later, if deemed necessary.16 The first task would be to find sufficient troops for the mission.

In seeking the troops required, the British administration ignored diplomatic niceties when communicating with the self-governing Dominions, and, in particular, with Canada. On 20 July, Walter Hume Long, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, sent a telegram to the Duke of Devonshire, the Governor General of Canada, laying out the requirements for the Canadian contingent, and stipulating that all participating units, except one infantry battalion coming from Hong Kong, would be Canadian. The telegram ended by noting that Canada could be expected to furnish a third infantry battalion, if the British battalion withdrew.17

CWM 19710261-0328

Smouldering Russian Army Storehouse Burnt by the Bolsheviks, painting by Colonel Louis Keene.

This correspondence was sent without consulting either Borden or Mewburn, both of whom were in London attending the Imperial War Cabinet meetings at the time. This action demonstrated that the British administration still did not recognize the independence of the Canadian government in making its own decisions regarding the use of its own army, and considered the Governor General to be acting as a British agent. The Canadian ministers were so incensed that Borden telegraphed Ottawa, ordering “...no reply shall be sent to the British Government’s message except through me.”18

On 27 July 1918, at the Imperial War Cabinet meeting, the CIGS acknowledged that the correspondence to the Canadian Governor General had disturbed the Canadian Minister of Militia. Borden agreed that General Mewburn had been annoyed, but that he, Sir Robert Borden, did not wish to dwell upon the matter. He did grant that Canada was to send three battalions and some engineers to Siberia.19 Discussion continued on what transportation would be required to take the troops from Canada to Russia. The Director of Military Sea Transport, E.J. Foley, explained that there was sufficient shipping available in the Pacific to transport 10,000 men, but that some of it was in China, and it could take up to a month to make port at Vancouver. He noted, however, that at least two ships could arrive at that port in short order to transport up to three battalions overseas within just a few days. At that point, Lloyd George suggested that Prime Minister Borden take charge of the transport for the troops on behalf of the Imperial War Cabinet. The War Office and the Ministry of Shipping were to make people available to the Canadian Prime Minister to expedite the transportation requirements.20 Borden also queried whether there would be diplomatic problems if Canadian troops arrived in Vladivostok before the American-Japanese discussions on intervention were completed. He was assured that at least one British battalion would be in place already regardless, and that it was expected that the Japanese would have published their declaration of a lack of interest in acquiring Russian territory, or for interfering in Russian internal affairs, before any Canadians arrived.21

The day after the Imperial War Cabinet put Borden in charge of transportation for the Siberian intervention, the Canadian Prime Minister received a reply from Ottawa on the correspondence sent by the British Government to the Canadian Governor General. The Canadian Cabinet approved the inclusion of Canadians in the Siberian Expedition, and left it to Borden to arrange all the details.22

The administration of the Canadian contingent became the purview of Militia Headquarters in Ottawa. However, much of the Siberian command staff, and the commander himself, first assembled in London under the control of the Canadian headquarters already established there. Thus, for a time, responsibility for the expedition’s organization was split between Ottawa and the Canadian Overseas Ministry, residing in London.

CWM 19710261-0323

Infantryman in Full Kit, painting by Colonel Louis Keene.

On 7 August, Borden asked for an expedited Order-in Council from his Cabinet to allow the creation of the Siberian force.23 A little over a week later, on 16 August, the commander designate of the force, Brigadier-General J. H. Elmsley, petitioned Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Turner, the Canadian Chief of General Staff in London, for the official stand-up of an independent command for Siberia, separate from the Canadian Overseas Forces.24 These two actions indicated the complex administration involved in instituting the Canadian Siberian force. In addition, some aspects of organizing both contingents were complicated by the presence in London of both the Canadian Prime Minister and the Minister of Militia during the month of August. Decisions needing the Prime Minister’s approval were expedited, but those that required Canadian Cabinet discussion needed letters and telegrams to be answered from Canada. Borden further complicated matters when he told his Cabinet that the United Sates and Britain were sending economic commissions with their military contingents and that he “...considered it essential that Canada should take like action.”25 National self-interest became an important factor in organizing a military expedition, even for a small ally such as Canada. Borden did not want Canada to be left behind in any economic advantage that might accrue from the Siberian expedition, especially when he was aware that both Britain and the Japanese were establishing economic commissions in the Russian territory.

While the Canadians were organizing their contingent, the Americans announced their decision to send troops to Siberia in order to work with the Japanese to assist the 70,000-strong Czech-Slovak Legion with its escape from Russia. Thus, aid to the Czech-Slovak Legion was the official excuse President Wilson used to have American troops intervene in the region. Additionally, on 3 August 1918, the first contingent of the British Empire’s commitment entered Siberia with the arrival at Vladivostok from Hong Kong of the 25th Middlesex Regiment.26

Delay was endemic to the Siberian expedition. The decision to send Canadians as the majority of the British contingent had been made quickly. The details governing the operation became bogged down in argument. What Canada would pay for and what Britain would pay for had to be agreed upon. What lines of communication would be established between Elmsley and Ottawa, and between Elmsley and the War Office had to be decided, as well as to what extent operational control of the force would be shared between Canada and Britain.27 In addition, the desire that the force consist of volunteers meant that a recruiting drive had to be accomplished among troops who had returned to Canada, and also within the general population of Canada. The creation of this new force would generate competition to the search for reinforcements for the Western Front. Mewburn had requested from Borden that the force should be voluntary, so as not to interfere with finding reinforcements for France, and Borden had agreed to this request.28 This new force also had to be sanctioned by the Canadian Government through an Order-in-Council, which was finally passed on 23 August 1918.29

Mobilization was a major task, but transportation of the force and the governance of the contingent were both contentious issues. At the end of July, Borden had accepted Lloyd George’s tasking to oversee transportation of the British Siberian contingent to Vladivostok. However, the Canadian Prime Minister had to rely upon the expertise of the British Ministry of Shipping to organize transports from the west coast of Canada. In light of the fact that the majority of the troops were to be Canadian, and were to embark from Vancouver, the Admiralty requested that ships drawn from the Canadian shipping registry be employed for the task. Accordingly, the Canadian government was asked to issue appropriate orders to the Canadian Pacific Ocean Services, and to the Dollar Company.30

The Canadian Cabinet considered the ships that the British government proposed to use inferior for the purpose. In a letter to Mewburn, Colonel C.C. Ballantyne, the Canadian Minister for Marine, noted that the ships designated were very slow (7.5 knots), could not carry horses and “...[were] really not fit to carry troops...”31 Ballantyne urged that the Empress of Russia and the Empress of Asia be recalled to act as transports. This concern for what ships were to be used appears to have annoyed the British Ministry of Shipping. Walter Long, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, wired the Governor General, noting that the Canadian Militia authorities were negotiating for the shipping. Long then said that it was essential that the Ministry of Shipping keep control of the negotiations, and also have the authority to requisition ships.32 Despite Borden having been put in charge of transportation, it appears that the Ministry of Shipping retained control, since those ships selected were not the best suited for the task. Mewburn told Borden that the ships originally selected, “... are hardly fit to carry horses.”33 Nevertheless, Ballantyne had some success with the shipping agents, as the Empress of Japan was the ship within which the first part of the force embarked.

Canada fared better in asserting control over her troops in Siberia. Since the majority of the British troops were to be Canadian, and the commander was also to be Canadian, Borden and Mewburn decided that their government would retain control of the employment of their own citizenry. This decision was made, despite the fact that the overall operational control lay with the British War Office. On 13 August, Borden wrote to Mewburn that, due to the distance of the operation from Canada, and the uncertainty of conditions, Elmsley should have complete freedom to decide the disposition of Canadian forces. Borden also noted that Canada would not be justified in moving troops into the interior of Siberia without first knowing the details of the proposed campaign, and the command arrangements involved.34

This opinion led to a draft memorandum to the War Office that laid out the governance aspects of the force with respect to Elmsley and the Canadians, and how the Canadian Government wished to operate in context. The memorandum required that Elmsley always have direct communications with his government, and that Canadian troops would not be involved in any operation without the sanction of the Canadian Government.35

On 4 September 1918, the War Office produced a counter-proposal that opted to have the Canadian contingent operate under the same command structure as that in place in France. Elmsley would have the right to appeal any order he considered dangerous to the British Government, with ‘information copies’ being provided to Canada.36

The Canadian Government took the British request under consideration, and on 7 September, Mewburn asked for Borden’s view, while awaiting comment from Elmsley and Kemp in London.37 Elmsley’s reply was sent on 10 September. He acknowledged that the force was under War Office control, but noted that no plan of operation had been agreed upon by all the nations involved, and he asked that, if the British version of the governance proposal was accepted, then no action on any appeal of orders by Elmsley would be decided before the Canadian Government was consulted.38 He also wished to have direct communication with the Canadian authorities. Thus, Elmsley desired to have some ‘safety valve’ for redress to his own government, in case orders he received from foreign commanders clashed with his own view, or they endangered Canadian soldiers.

This situation echoed the events that had occurred in 1917 for Britain. Field Marshal Haig had objected to General Ferdinand Foch being made Generalissimo of all Allied forces in France, which made all British forces subordinate to French command. Haig had sought the right to appeal French orders to his own government. A compromise eventually was agreed upon between the two Allies that allowed Haig to forward his objections to the British War Cabinet, while simultaneously proceeding with the orders, to the point of execution. Thus, the Canadians were seeking the same rights as the British commander had obtained in a similar situation. However, as it materialized, the day that Elmsley sent his views to Canada was the same day the War Office issued their orders to him, and the same day Mewburn sent the Canadian government’s desired changes to the British proposed amendment.

The original British orders, signed by the CIGS, officially appointed Major- General Elmsley as commander of British forces in Siberia, and subordinated him to the Japanese Lieutenant-General Keijiro Otani, the Commander-in-Chief of all Allied troops in the Russian Maritime provinces. The directions also described Elmsley’s relationship with Major-General Knox as one of keeping the other informed of events, rather than one of ‘superior’ and ‘subordinate.’ Knox had been issued similar orders in a separate telegram in late August, which specifically named Elmsley as British commander and himself as the British liaison officer to Otani.39 The instructions to Elmsley also required him to keep in touch with Sir Charles Eliot, the British High Commissioner in Siberia, with respect to political matters. The orders, as issued, stated that the British force would operate in Siberia exactly as British forces acted in France, and the wording of the order concerning communication with the Canadian government was identical to that proposed by the British government on 4 September 1918.40

The Canadian reply to the British demonstrated Canada’s view of its own independence. The message stated that before Canada committed its troops to Siberia it required that information concerning expected general operations be passed to Canada. In addition, Canada wanted to know ahead of time what part the United States would play in these operations. The message altered the British proposed orders to stipulate that no appeal of Elmsley’s would be decided against him, except with the express approval of the Canadian government. Canada also ordered that Elmsley could correspond directly with the Canadian government without any reference to the War Office, or to any other outside authority.41 The War Office accepted the Canadian amendment.

On 6 October 1918, the War Office issued a change to Elmsley’s orders that added the Canadian amendment, word-for-word, to the paragraph that referred to his relationship with General Otani and the War Office.42 Canada had asserted its independence in operational matters where Canadian troops were concerned, and had met with little resistance from the British. The reason for War Office acquiescence was that the British government was desperate for troops, and Canadian troops were the only soldiers available at the time. Moreover, Siberia was a sideshow, with the Japanese in command of military operations.

Although the Japanese were nominally in charge of the Allies in Siberia, on 9 September, the anti- Bolshevik Russians met in Ufa, Siberia, to set up their own government. The disparate groups had only their anti-Bolshevik views in common, and it took until 21 September for the conference to nominate five leading Russians as the Provisional Government.43 This group acted as the Russian government, but without the backing of many of the Russians in the area. All these events occurred while Canada was creating its expeditionary force.

CMJ collection

A Canadian soldier standing chilly sentry duty in Vladivostok.

Getting Going

While the details of establishing the force were being decided between the Canadian and British governments, the force was being assembled in Canada. Although Mewburn had stipulated that the force would be raised from volunteers who had returned from the Western Front, this was found to be impossible. Conscripts, who had been enrolled under the Military Service Act, had to be employed to make up the total complement of the force. The majority of the brigade consisted of two infantry battalions, the 259th Canadian Rifles and the 260th Canadian Rifles, two batteries of artillery, a machine gun company, and a squadron of cavalry drawn from the Royal Northwest Mounted Police. The remainder of the brigade was posted to the headquarters or served in support functions for the fighting troops.

The 259th Battalion was an example of a specially formed unit, consisting of two companies drawn from Ontario and two from Quebec. The two Quebec companies were mostly conscripted men from Montreal and Quebec City, the one area of the country that most resented conscription, and had in fact rejected it in the 1917 referendum and election. Of the1083 men in the Battalion, only 378 were volunteers.44 This proved problematic for the Brigade, and it led eventually to a mutiny among some of the Quebec soldiers in December, prior to embarkation for Russia. The 260th Battalion was drawn from the other provinces; one company from Atlantic Canada, one from Manitoba, one from Saskatchewan and Alberta, and the last one came from British Columbia.45

The main body of the Canadian brigade was formed in Vancouver during the autumn of 1918. The advance party assembled in Victoria on 3 October. It was scheduled to sail to Russia a week later, and consisted of part of the headquarters staff, as well as service support elements for administration, medical support, logistics, and food preparation.46 This advance party of 706 troops, led by Elmsley, sailed from Victoria on 11 October 1918 in the Empress of Japan, and they arrived in Vladivostok on 26 October.47 Sixteen days later, the war in Europe ended when an armistice was signed between Germany and the Allies on 11 November 1918. However, the only impact the Armistice had upon the forces intervening in Russia was to change the status of the ‘enemy.’ It also started the political manoeuvring between the Canadian government and the British to evacuate the Canadian contingent back to Canada.

Some members of the coalition forming the Canadian cabinet, especially those from political parties other than that of Sir Robert Borden, began to urge for the quick return of the Canadian soldiers overseas, and they started questioning why Canadians were fighting in Russia in the first place. However, these questions did not begin until Borden had left to attend the anticipated Peace Conference in Europe. The Prime Minister had left for England as soon as an armistice was about to be signed, having informed the Colonial Office and Lloyd George of his intentions to leave Canada by 10 November 1918.48 Before the Canadian Prime Minister arrived in Britain, Acting Prime Minister Sir Thomas White telegraphed Sir Edward Kemp in London to have him table discussions about the Siberian Expedition, because, “...All our colleagues are of the opinion that public opinion here will not sustain us in continuing to send troops ... now that the war is ended.”49 White sent a second cable the following day, stating that the Militia Department wanted direction as soon as possible on whether to continue the expedition. On 20 November, Borden replied that, having consulted with the War Office, there was little danger to Canadian or British troops of offensive action, and that their presence was a stabilizing factor for the Russians. He believed that the Canadians should remain in Siberia until the following spring, and Canada should continue sending the troops promised.50 Therefore, the Canadian expedition to Siberia was foreseen to continue for some time yet, but from Borden’s telegram, there was no expectation of serious fighting. Borden, the politician, was hedging his bets, trying to please the British, while placating the politicians and the public at home.

However, General Elmsley was concerned over a lack of clear orders, and the fact that there was no independent Canadian military policy. On 11 November, he wrote to Sir Charles Eliot. Elmsley noted that, with the armistice, he expected orders that placed him under the command of the Japanese would be modified. Notwithstanding, Elmsley observed: “The Canadian Government has stipulated, and the British Government has agreed, that my Force shall not be committed to any military operation without carrying my judgement, and that in this respect, I have the right of appeal to both the British and Canadian Governments.”51 The Canadian commander was setting the scene for independent action, regardless of the wishes of the Japanese, and he was echoing the actions of the American commander, who had retained independent control of American forces from the time of their arrival in Siberia.

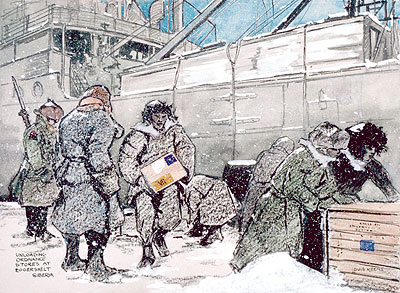

CWM 19710261-0325

Unloading Stores, Eggershelt, painting by Colonel Louis Keene.

Despite Borden’s convictions, and a fear that opting out of a firm commitment to the British would damage Canada’s newly won prestige, he left final judgment to continue the expedition to his Privy Council, and the Privy Council was divided on the issue. Thomas Crerar, the Minister of Agriculture, and a leader of the Unionist Party (Liberal) in the Coalition Government, wrote to White, saying: “I cannot agree that the retention of our forces in Siberia, and the sending of further Forces there, can be justified upon the ground of the necessity of re-establishing order in Siberia. The matter of how Russia shall settle her internal affairs is her concern - not ours.”52 Nevertheless, the Privy Council agreed to continue with the expedition, but it placed a caveat upon the force that it would not be permitted to move inland , or take part in military operations. The Privy Council also asked that a clearly defined military policy be articulated by the British government, and hinted that without this policy statement, the Canadians would be withdrawn.53 The Privy Council also stated that Canada’s commitment would end in the spring of 1919.54 In answer to this telegram, the War Office suggested that the two British battalions in Siberia’s interior be withdrawn to Vladivostok, and that the Canadians be returned to Canada. At a minimum, the War Office suggested that no more Canadians be sent from Canada, and those then at sea should be returned home.55 The Canadians demurred on this suggestion for some time.

The Siberian contingent continued to mobilize in Vancouver (New Westminster, Coquitlam) and Victoria (Willows Park), where 5000 soldiers were undergoing training. Canadians sailed from Vancouver to Vladivostok throughout the autumn and winter, but not without incident. The Canadian government had become concerned, because socialist politics and labour unrest were on the rise in the country. In Victoria, some labour agitators convinced a number of the Quebec members of the 259th Battalion to mutiny by refusing to embark for Russia. This resulted in twelve arrests, and the subsequent courts-martial of the ringleaders. In the end, other soldiers with fixed bayonets escorted the two Quebec companies aboard ship.56 And so, ultimately, by one method or another, Canadian servicemen still carried out the duty then required of them.

Conflict was also growing between Generals Elmsley and Knox in Siberia. Knox advocated to Elmsley that the Canadian commander should use his troops against the Bolsheviks in support of the provisional Russian government, now headed by Admiral Aleksandr Vasilyevich Kolchak. The Americans and Japanese remained neutral towards the anti-Bolshevik government, but the Czechs were becoming frustrated with Russian actions. Knox hoped that the Canadians could join the two British battalions supporting Kolchak around Omsk in the middle of Siberia.

Denouement

General Elmsley was tied by his orders from Ottawa, but he sent small parties to serve as guards on supply trains, and he allowed Lieutenant-Colonel T.S. Morrisey, along with 55 men, to proceed to Omsk and to act as headquarters staff for the two British battalions stationed there.57 For the remainder of the troops at Vladivostok, the deployment became a task of fighting boredom. Sentry duty and administration taskings were the orders of the day. However, pressure was building from the Cabinet at home, and, in February, White queried Borden as to when the Canadian troops would be returning to Canada.58 Borden took action by informing Lloyd George that he considered April as the time to withdraw Canadians from Siberia.59 Coincidently, only in April was there a hint of action for the Canadians. This occurred at a small village called Shkotova, located north of Vladivostok near Olga Bay.

On 12 April 1919, Bolsheviks surrounded the village where Russian troops, loyal to Kolchak, were holding prisoners. It was feared that the Bolsheviks would capture the whole village and endanger the mine in the vicinity. The Japanese commander called for an Allied force to rescue the Russians in the village, but the Americans refused to take part.60 The Canadians sent a company from the 259th Battalion to be part of the rescue force.61 However, when they arrived at the village on 19 April, the Bolsheviks had already dispersed, and the force returned to Vladivostok two days later without having fired a shot. The only positive outcome for the Canadians from this operation was the Japanese gift of 96 bottles of wine, 18 bottles of whisky, and 3 casks of sake, in grateful acknowledgement of the efforts of the Canadian troops.62

Canadians commenced the return from Siberia on 22 April 1919, and the last member of the Canadian Expeditionary Force left for home on 5 June 1919. The departure of the Canadians from Siberia precipitated the departure of the rest of British forces, who first decamped to Vladivostok by the end of summer. The bulk of the Americans departed Siberia in the autumn, and the last of the British military mission left in March 1920.63 Of all the major Allies, soon, only the Japanese remained, and they subsequently retreated to Sakalin Island, departing there for the Home Islands in 1922. Thus ended the ill-fated Allied intervention into Russia. But the enduring legacy of this intervention into Russia’s civil war would be Soviet antipathy towards the West for the next 70 years.

![]()

Commander Ian Moffat has been a naval officer and an operational sailor for over 35 years. He is currently working on his PhD thesis in War Studies on the Canadians in Siberia experience at the Royal Military College of Canada.

Notes

- War Cabinet Minute 443, 10 July 1918, United Kingdom, Public Record Office Cabinet Papers (hereafter PRO Cab) 23/7. During this meeting, no mention was made of Reading’s 9 July 1918 telegram, informing his government of Wilson’s decision to intervene in Siberia.

- Ibid., and War Cabinet Minute 445, 15 July 1918, PRO Cab 23/7.

- Lloyd George to Reading, telegram 4473, London, 18 July 1918, United Kingdom, Public Record Office Foreign Office documents (hereafter PRO FO) 371/3319/125173. Lloyd George specifically asked Canada to fill the commander’s position with a brigade headquarters and a signal section, and to provide two infantry battalions with reinforcements, a battery of artillery, a machine gun company, and service support in the form of transport, medical and supply troops, for a total of 4000 men.

- B.B. Cubit to Secretary, Overseas Military Force of Canada, letter 0149/5122. (S.D.2), London, 12 July 1918. Canada, National Archives of Canada (hereafter NAC) MG 27 II D9 Volume 159, File R-25 – Russia – North 1918-1919.

- Gaddis Smith, “Canada and the Siberian Intervention 1918-1919,” in The American Historical Review, Vol. LXIV (October 1958 to July 1959), p. 867.

- Knox, Memorandum, 7 June 1918, as quoted in Ibid.

- War Cabinet Secret Minutes X-13, 14 June 1918, PRO Cab 23/17. Borden had criticized the High Command for being slow to adopt innovations that later proved necessary, but whose delay in implementing these innovations cost unnecessary casualties. Lloyd George agreed, and, at this meeting, instituted a Committee of Prime Ministers to make recommendations.

- Robert Borden, Robert Laird Borden: His Memoirs, Henry Borden (ed.), (Toronto: The MacMillan Company of Canada, 1938), p. 827.

- Imperial War Cabinet Minutes 19B, 24 June 1918, PRO Cab 23/44A.

- Imperial War Cabinet Minutes 20A, 26 June 1918, PRO Cab 23/44A.

- War Cabinet Secret Minutes X-3, 17 May 1918, PRO Cab 23/17.

- Major General Percy de B. Radcliffe to W. Newton Rowell, War Office letter (Secret & Personal), London, 9 July 1918, NAC MG 27 II D 9 Vol. 159, File R-25 Russia -Siberia 1918-1919. The fact that General Radcliffe asked Rowell to intercede with Borden for Canadian participation in the intervention in Siberia and that General Bridges had sought Canadian aid from the Canadian Militia Headquarters in Ottawa the week previously shows that Britain had already decided to intervene with or without the Americans. This contradicts Keenan, who surmised that the British had not decided to intervene until 10 July, when Lloyd George received Reading’s 9 July telegram, which stated that Wilson had decided to send American troops to help the Czechs in Siberia. This is also Gaddis’s conclusion in his paper. See Keenan, Decision to Intervene, p. 408, and Gaddis, pp. 868-869, Footnote 7. The War Cabinet Minute 443, 10 July 1918, confirms the British made their decision to intervene in Siberia independent of knowing that President Wilson had agreed to intervention.

- Mewburn to Borden, letter, London, 12 July 1918, Borden Papers NAC OC 516-OC 518 (2) MG 26 H 1 (a) Vol.103, pages 55514 to 55538, and pages 56124-56191 Reel C – 4333(hereafter Borden Papers), 56127.

- P. de B. Radcliffe to Mewburn, letter, London, 12 July 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56128.

- Mewburn to Gwatkin, telegram, London, 12 July 1918, Borden Papers, pp. 56129-56130.

- Foreign Office to Sir William Conygham Greene, telegram 692, London, 20 July 1918, PRO FO 371/3319/126238 and War Cabinet Minute 450, 22 July 1918, PRO Cab 23/7.

- Long to Devonshire, telegram, London, 20 July 1918, in Canada, Department of External Affairs, Documents on Canadian External Relations Volume I 1909-1918, (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1967) (hereafter CER), p. 206.

- Borden to Cabinet (Ottawa), telegram, London, 25 July 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56135.

- War Cabinet Secret Minutes X-26, 27 July 1918, PRO Cab 23/17. It must be noted that the title of this paper is “Notes of a Conversation at 10 Downing Street.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Doherty to Borden, telegram, Ottawa, 28 July 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56141.

- Borden to Acting Prime Minister White, telegram, London, 7 August 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56145.

- Elmsley to Turner (CGS), letter, London, 16 August 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 3 Vol. 371, File A3, SEF folder Force HQ 27 Mobilization Generally.

- Borden to White, telegram, London, 8 August 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56149.

- John Ward, With the “Die Hards” in Siberia (London: Cassell and Company Ltd, 1920), p. 3.

- “Notes on Conference held in General Radcliffe’s Room, War Office – 12.00 noon August 13th, 1918”, London, 13 August 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 3 Vol 371 File A3 SEF folder Force HQ 27 Mobilization Generally.

- Mewburn to Kemp, letter, London, 13 August 1918, Borden Papers, pp. 56166-56167.

- Order-in-Council 2073 – 23 Aug 1918 – Formations of C.E.F for service in Siberia File 9-78, NAC RG 9 III A 1 Vol. 98 file 10-14-19 (Part II, III & VI) Lists of Orders in Council.

- Perley to White, telegram, London, 14 August 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56175.

- Ballantyne to Mewburn, letter, Ottawa, 27 August 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56178.

- Long to Devonshire, telegram, London, 30 August 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56180.

- Mewburn to Borden, letter, Ottawa, 10 September 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56186.

- Borden to Mewburn, letter, London, 13 August 1918, Borden Papers, pp. 56162-56163.

- Gow to Mewburn, telegram Y1138 CATSUP, London, 4 September 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56182.

- Ibid.

- Mewburn to Borden, letter, Ottawa, 7 September 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56185.

- Gow to Mewburn, telegram Y1192 Catsup, London, 10 September 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56187.

- War Office to Knox, telegram 65077 cipher M.I., London, 26 August 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 2 Vol. 362, File A3 SEF folder 114 Conferences, Instructions, Orders in Council, Royal Warrents CEF (Siberia).

- CIGS to Elmsley, General Staff orders 0.1/173/496, London, 10 September 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 2 Vol.362, File A3 SEF folder 114 Conferences, Instructions, Orders in Council, Royal Warrents CEF (Siberia).

- Mewburn to War Office, draft telegram Y1192, Ottawa, 10 September 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56189.

- War Office to Elmsley, telegram 6799 War Office 68032 cipher FMO, London, 6 October 1918, as cited in CIGS to Elmsley, General Staff orders 0.1/173/496, London, 10 September 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 2 Vol. 362, File A3 SEF folder 114 Conferences, Instructions, Orders in Council, Royal Warrents CEF (Siberia). Mewburn to War Office, draft telegram Y1192, Ottawa, 10 September 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56189.

- Harris (US Consul at Irkutsk) to Lansing, telegram 108, Irkutsk, 21 September 1918, File No. 861.00/2764 FRUS 1918 Russia Vol II, 385-386 and Kettle, p. 349.

- Benjamin Isitt, “Mutiny from Victoria to Vladivostok, December 1918,” in The Canadian Historical Review 87, No. 2 (June 2006), p. 239.

- Roy MacLaren, Canadians in Russia 1918-1919 (Toronto: MacMillan of Canada, 1976), pp. 146-147.

- R.Gwynne, circular memorandum E.H. C No. 2514, Ottawa, 21 September 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 3 Vol. 367, File A3 SEF Folder B-H 20-2 Movement of Troops Re: Instructions.

- John Swettenham, Allied Intervention in Russia 1918-1919 and the Part Played by Canada (Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1967), p. 128, and R. Gwynne, circular memorandum E.H. C No. 2514, Ottawa, 21 September 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 3 Vol. 367, File A3 SEF Folder B-H 20-2 Movement of Troops Re: Instructions; Isitt, p. 240. Swettenham says 680 personnel went in the advance party, Isitt says the number was 677, and the actual order lists 706 servicemen.

- War Cabinet Minutes 496, 4 November 1918, PRO Cab 23/8; Borden to Lloyd George, telegram, Ottawa, 28 October 1918, and Borden to Lloyd George, telegram, Ottawa, 6 November 1918, in CER Volume I 1909-1918, pp. 218-219.

- White to Kemp, telegram, Ottawa, 14 November 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56216.

- Borden to White, telegram, London, 20 November 1918, Borden Papers, pp. 56221-56222.

- Elmsley to Eliot, letter GCS C 1-16, Vladivostok, 11 November 1918, NAC RG 9 III A 2 Vol. 362, File A3 SEF folder 114, Conferences, Instructions, Orders in Council, Royal Warrents CEF (Siberia).

- Crerar to White, letter, Ottawa, 22 November 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56232.

- J.E. Skuce, CSEF Canada’s Soldiers in Siberia 1918-1919 (Ottawa: Access to History Publications, 1990),p. 9.

- Gwatkin to War Office, telegram 500B, Ottawa, 23 December 1918, Borden Papers, p. 56333.

- War Office to Gwatkin, telegram 73422, London, 4 January 1919, Borden Papers, p. 56336.

- Benjamin Isitt, “Mutiny from Victoria to Vladivostok, December 1918,” in The Canadian Historical Review Vol. 87, No 2, (June 2006), pp. 223-264.

- Skuce, p. 10.

- White to Borden, telegram, Ottawa, 5 February 1919, Borden Papers, p. 56388.

- Borden to Lloyd George, letter, Paris, 7 February 1919 Borden Papers, p. 56390.

- Intelligence Report 7 “The American AttitudeTowards the Shkotovo Expedition,” Vladivostok, 13 April 1919, NAC RG 9 III A-2 Vol. 357, File-A3 SEF files 1&2 Folder Shkotovo Expedition April 1919.

- LCol R.W. Stayner to Major M. M. Hart (B Company Commander), Instructions G.W.B. F.H.Q. C. 90, Vladivostok, 13 April 1919 NAC RG 9 III A-2 Vol. 357, File-A,3 SEF files 1&2 Folder Shkotovo Expedition April 1919.

- Swettenham, p. 177.

- Richard H. Ullman, Britain and the Russian Civil War November 1918-February 1920, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968), p. 253.