This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Canadian Forces Transformation

DND photo IS2007-7671 by Master Corporal Kevin Paul,

Canadian Forces Combat Camera

In the waters of the Indian Ocean off the coast of Somalia, HMCS Toronto practices high-speed manoeuvres in preparation for carrying out anti-piracy and NATO presence patrols in Somali waters.

On Broader Themes of Canadian Forces Transformation

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

In April 2005, the Government of Canada issued its current Defence Policy Statement (DPS) within the context of its International Policy Review. With the DPS, the government has called for an effective, responsive, and relevant 21st Century Canadian military – a force able to defend Canada and Canadian interests and values while contributing to international peace and security.1 In anticipating such a call, on 10 March 2005, the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), General Rick Hillier, directed the commencement of the first overall transformation of the Canadian Forces (CF*) since the mid-1960s.2

The pre-transformation CF was not effective, responsive, or relevant for the 21st Century. The current CF, undergoing transformation, is a mixture of both past and present existences, somewhere between where it was and where visionary leadership wishes it to be. The CDS’s vision foresees a networked CF, with an effective, capable, and integrated infrastructure operating under a ‘command centric’ umbrella.3 This proclaimed CF transformation provides a vital foundation for all of Canada’s national and international security strategies. It takes into account current and future strategic and threat imperatives for the sake of enduring CF institutional and operational effectiveness.4

DND photo SU2005-0468-03 by

CFSU (O) Photo Services

General Richard J. Hillier, Chief of the Defence Staff.

The transformation of the CF cannot be achieved by a simple flick of a switch. In this era of perpetual uncertainty, ‘people’ are learning how to think and act outside their known comfort zones. Such learning requires time, dedication, and individual and institutional effort. Societies are in the midst of significant transition, moving away from all that was once known to something that, today, is not very well known, and that, tomorrow, will be completely unknown.5 Consequently, people are ‘testing the waters,’ trying to bring substance to current uncertainties by identifying themes of the past. Everyone is searching for new parameters “...trying to identify the components needed to build an organization that can achieve breakthrough performance in the knowledge era of tomorrow.”6 The CF is no exception. Successful CF transformation depends upon leadership first identifying and understanding the thematic components of the past, and then, learning how to adapt and exploit the thematic strengths ‘today’ for the benefit of ‘tomorrow.’

Civil-Military Relations

Broadly defined, civil-military relations “...refers to the relationship between the armed forces of the state and the larger society they serve – how they communicate, how they interact, and how the interface between them is ordered and regulated.”7 The field of civil-military relations provides a strong political, sociological, and historical springboard for launching a study of the Canadian military. This preliminary analysis is rooted in the Cold War foundational writings of Harvard political scientist, Samuel P. Huntington, and military sociologist, Morris Janowitz.

In his groundbreaking book, The Soldier and the State, Huntington argued that a military’s autonomous nature was directly related to its ability to act effectively in times of war. He further argued that the only way to protect the autonomous nature of a military was to shield it against two main inhibitors – primal human existence and restrictive civilian control. He hypothesized that such protection was only available by maximizing military professionalism, because “...professionalism was what distinguished the military officer of today from warriors of the past.”8 Huntington assumed that a highly educated professional officer corps would result in civilian authority listening to and respecting its military leadership. This, in turn, would lead to civil authority understanding the military’s primary purpose and supporting its needs. As a result, any restrictions placed by civilian authority upon the military’s autonomy would not influence overall military effectiveness.9

In contrast, in his many writings, Janowitz’s main premise held that 21st Century militaries existing in a global world inundated by social, economic, and political turmoil, would do so, not as battle forces, but as socially integrated constabulary forces; that the past assertion of using maximum force to attain victory at all costs would have no place in this new ‘post-modern’ world. More precisely, Janowitz argued that a military is constabulary in nature, when “...it is continuously prepared to act, committed to the minimum use of force, and seeks variable international relations, rather than victory, because it has incorporated a protective defensive position.”10

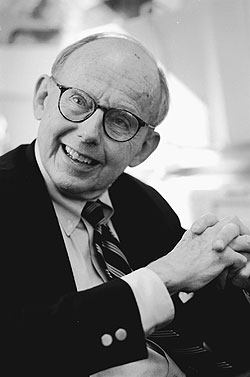

Photo by Carl Walsh/Aurora/Getty Images

Harvard icon of political science Samuel P. Huntington.

Janowitz suggested that questionable policies of civilian control, and the gradual erosion of the primary purpose of a traditional military, inevitably would combine to weaken militaries as independent, distinct entities. Such weakening, in turn, would encourage a rise in military member frustrations, and would precipitate ever-increasing military hostility against civilian authority and anti- militaristic social views. He summed up his overall argument by stating that these types of military responses would only be controllable by government enforcing the constabulary purpose of a military, regardless of military critical claims, and by putting in place an ever-increasing system of civilian checks and balances.11

His model holds that such checks and balances would include civilian authorities setting personnel standards and continually re-evaluating the military’s overall performance in accordance with governmental policy and societal acceptance. Arguably, the implementation of such a model would breed discord and distrust between a government and its military instrument, with the ‘pro-military’ Huntington supporters endeavouring to gain control over their own profession, and the so-labelled ‘anti-military’ Janowitz supporters undercutting or disregarding such effort in the face of tighter and tighter civilian control.

As a side point, Todd S. Sechser’s 2004 conflict resolution study provides a slightly different argument.12 Sechser determined that a strong degree of civilian control over a military directly equates to a decrease in the number of military actions a government will pursue, and that weak civilian control leads to excessive military action.13 In doing so, he rejected the ‘conservative’ argument that a decrease in the number of military actions is directly attributable to military leadership consistently advising government against using force unless absolutely necessary.14 Instead, he argued that it is strict civilian control that prevents an ever-increasing escalation of the number of military deployments.15

Thus, civil-military relations includes, on one hand, a military that has coercive willpower to be victorious over an identified enemy of society; and, on the other, the government that, in representing society, has the responsibility of making sure that a military’s coercive willpower is never used against its citizenry. This responsibility includes the point that any military use of violence must always be legally authorized, socially justified, and popularly accepted. As such, governments are responsible for advising and educating the citizenry so as to make educated choices about a country’s military purpose and direction. The civil-military “challenge is to reconcile a military strong enough to do anything civilians ask them to do with a military subordinate enough to do only what civilians authorize them to do.”16

The contemporary field of civil-military relations in Canada finds itself sitting somewhere between the Cold War theories of Huntington’s traditional political view of military professionalism and Janowitz’s post-modern sociological perspective. As expressed by a senior military leadership analyst, Karol Wenek, the question facing CF leadership in 2002 and into the future decade was: “How clear are the distinctions between professional and institutional obligations in an integrated defence headquarters and how does one resolve the conflicts between them?”17 More accurately, given the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Canada’s current United Nations commitments in Afghanistan, the above-noted theories no longer apply in contemporary times, and they no longer explain civil-military relations in Canada or elsewhere.18

Regardless of these semantics, aspects of both foundational perspectives are found within the past and current trials of the Canadian Forces. The future is sure to involve similar controversy – with the civil-military relations pendulum swinging back and forth creating inevitable havoc unless both military and civilian leadership work together to anticipate, understand, adapt, and exploit such movement.

Professional-Bureaucratic Duality

As described by Christina Balis in her pivotal PhD dissertation on military professionalism in Europe, professionalism is an ever-evolving and elusive term befuddled by bureaucracies, a term having no fixed description, usually dependent upon the writer’s academic persuasion.19 Generally, writers have defined the term ‘professional’ by identifying and analyzing its different attributes. For example, in 1963, Bernard Barber determined four essential elements of common professionalism found throughout the 20th Century:

... a high degree of generalized and systematic knowledge; primary orientation to the community interest rather than the individual self-interest; a high degree of self control of behaviour through codes of ethics internalized in the process of work specialization and through voluntary associations organized and operated by the work specialists themselves; and, a system of rewards (monetary and honourary) that is primarily a set of symbols of work achievement.20

In dealing specifically with military professionalism, in 1957, Huntington produced a definition, based upon three main attributes: corporateness, expertise, and responsibility.21 In sum, these three attributes equate as follows: 1) corporateness – military identity; 2) expertise – knowledge; and, 3) responsibility – accountability.22 Following suit, Janowitz outlined several elements, including expertise, education and training, group identity, and civilian administration.23 Recently, James Burke, a professor of sociology at Texas A&M University, also based his sociological study upon three attributes: expertise, jurisdiction, and legitimization.24 Finally, in her 2005 dissertation, Balis used three similar attributes: expertise, autonomy, and bureaucracy.25

Notions of bureaucracies find their roots in the views of Max Weber.26 These notions have evolved to include the attributes of rationalization, standardization, and specialization; all deemed “central to the military profession.”27 In fact, a well-functioning professional-bureaucratic dichotomy is generally perceived as crucial to the operational execution of a modern military institution.28 Huntington first identified this co-existence by noting: “The officer corps is both a bureaucratic profession and a bureaucratic organization.”29 Throughout her research, current Emeritus Professor at the University of Hull in England, Gwyn Harries-Jenkins, developed this requirement for ‘balance’ by arguing that contemporary militaries will reach their fullest operational potential only by existing as “highly professionalized bureaucracies.”30

Confusion is inevitable, for, universally, one of the defining characteristics of military professionalism is the fact that military professionals ‘serve their country,’ agreeing to sacrifice their lives if lawfully ordered to do so. This military professional tenet of ‘unlimited liability’ is nowhere found within any description of a bureaucracy. It opposes any equal balance existing between a professional military and its bureaucratic organizational infrastructure. It is the concept of unlimited liability – completing a mission above all else including the giving of one’s life – that separates a military professional from bureaucratic public servants, civilian profes-sionals, academics, and everyone else. As Christina Balis articulates: “What makes a professional soldier distinct [from all others] ...is a highly developed sense of public service combined with an exceptionally high level of professional risk.”31

In context, contemporary Canadian military profes-sionalism is characterized by four main attributes: responsibility – duty to society; expertise – abstract theory and the knowledge possessed; identity – a member’s unique standing within society; and vocational ethic – the values and obligations underpinning the profession.32 All of these attributes subsume the concept of unlimited liability. For CF members, unlimited liability is viewed “...[as] integral to the military ethos and [as lying] at the heart of the military professional’s understanding of duty.”33

More to the point, unlimited liability is the foundational tenet of military professionalism. How the concept of unlimited liability may be understood or misunderstood by Canadian citizens, business employees, academics, and bureaucrats encompasses the uncertain civil-military relationship existing in Canada since, at least, the 1960s.

RMC photo

Mackenzie Building at Royal Military College, Kingston.

Individualism

The controversial relationship of professions and bureaucracies is affected further by the rise of the ‘rights of the individual.’ The shift in academic perceptions occurred in 1988 with the publication of sociologist Andrew Abbott’s, The System of Professions. With this publication, the nuances of contemporary ‘individualism’ and their influence over the bureaucratic dual essence of professionalism came to the fore. As condensed by Balis, Abbott’s argument was based upon his personal frustration over bureaucratic ‘employees’ proclaiming their professional status, when their actual actions and the “context in which they performed their actions” were more symbols of ‘deprofessionalization’ than examples of the professionalism they so ‘loudly’ proclaimed.34

It can be expected, then, that tensions will arise when both the bureaucratic and the individualistic nature of the pairing excessively dominate the professional aspects of the military organization. For example, renowned author and current professor at the United States Military Academy, Don Snider, in his study of military professionalism in the United States, addressed such aspects upon declaring that the current “...[United States] Army’s bureaucratic nature outweighs and compromises its very professional nature.... [for] officers do not share a common understanding of the military profession and many of them accept the pervasiveness of bureaucratic norms and [individualistic] behavior as natural and appropriate.”35

Snider’s study further alluded to the fact that when bureaucratic norms, supported by narrow-minded and career orientated leadership, dominate a military organization, individual members will find ways to manipulate the bureaucratic rules and procedures to their own personal advantage. Conversely, indi-viduals trying to live by the principles of military professionalism will be put at a distinct disadvantage, resulting in high levels of member anger, personal burnout, and attrition.36 Such individualistic actions work to undermine the professional-bureaucratic dichotomy and the very health of the military institution.37

The point is that while the bureaucratic nature of today’s militaries cannot be denied or ignored – for desired efficiency, proficiency of expertise, and adherence to authority and command are inevitable necessities in a military structure – such confinement must be tempered by professional thought, based upon service and duty, and not upon individual interests. Ultimately, when military organizations ignore this human element in lieu of technological capabilities and bureaucratic efficiencies, the professional deterioration of a military organization’s culture is not very far behind.38

This human element is deemed paramount, because ‘war and death’ depict the constant ‘human experience.’ Again, following Huntington’s Hobbesian perspective, “war” tends to bring out the animalistic aspects of human nature. For the protection of society and the overall effectiveness of the military establishment, such instincts must be kept in check by clear leadership and individual discipline – both grounded upon a strong military professional foundation. The crux of the matter is that military operational and strategic effectiveness are necessarily dependent upon the primacy of professionalism rising above individual desires and bureaucratic existence.

As articulated by Snider, if bureaucracy comes to predominate over military professionalism, two things happen. The first is that citizens become confused about their military’s purpose, they stop listening to their government representatives, who, ultimately, stop believing that their military is made up of military professionals expert in the art of warfare, and, consequently, stop believing that the military’s power is under civil control.39 The second is that the ability of a military to maintain and develop its own internal social controls and military professional ethos is lost, leading to “...a weakening of discipline among individuals within an institution capable of terrible destruction.”40

In sum, for militaries to adapt successfully in our uncertain world and to exist effectively within the contemporary civil-military construct, their leaders must agree to exist under ‘reasonable’ constraints applied by civilian control, while simultaneously “...safeguard[ing] their control over certain areas of internal jurisdiction, such as recruiting and professional socialization.”41 If one considers a military to be the same as any other civilian organizations, such reasoning begs the question: “How is society to protect itself from its own military?” if the military profession cannot be differentiated from any other.42

Individual Decision-Making

Societies, businesses, and militaries of today are struggling to balance the needs and desires of four generations of workers – the ‘Silent Generation’ (born 1933-1945); the ‘Baby Boomers’ (born 1946-1964); the ‘Generation Xers’ (born 1965-1976); and the ‘Millennials’ (born 1977-1988).43 The professional and employment beliefs coming out of these generations are vastly different from one another. Tensions arise when the Silent Generation’s traditional professional beliefs, based upon hard work, discipline, and self-sacrifice, conflict with the social and civil rights desires of the Baby Boomers, that, in turn, come up against the individualistic, self-centred, and immediate demand requirements of the Generation Xers. With the retirement of the Baby Boomer generation, the up-and-coming desires of the millennial generation surely will add to the complexity of the human resources workforce puzzle.44

Military organizations are not exempt from such generational changes. Such organizations must adapt to the fact that, in the 21st Century, the individual will have more sway over the direction of the organization than at any other time in recent history.

Photo by Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government

The noted Harvard professor and author Graham T. Allison.

Strategic Decision-Making

The interrelationship between professions, bureaucracies, and individuals becomes even more convoluted upon considering the bureaucratic-political decision- making model, first expressed by Harvard professor Graham T. Allison in his classic review of the Cuban Missile Crisis.45 In his masterpiece, Essence of Decision, Allison developed a decision-making model that determined that the Kennedy Administration’s decision-making process was ad hoc at best, with several individual entities and separate actions coming together accidentally to produce an outcome directly attributable to ‘the players in the game.’46 Allison’s model shows how decisions are made, based not upon fact, but upon the “...compromise, conflict and confusion of officials with diverse interests and unequal influence.”47 His model further outlines how strategic decision-making, based upon desires for consensus, personal interests, and strategic manipulation of the facts by individuals in positions of authority, results in outcomes devoid of flexibility, creativity, and forward-looking thinking.

Allison further asserted that, once made, decisions based upon unfounded, manipulative facts are subsequently bombarded by unexpected but avoidable implications arising out of the original unconsidered truths and rejected half-truths. He hypothesized that the result would be the gradual unravelling of the efficacy of the chosen decision, leading to rising hostility between the decision-makers, and increasing disrespect for the decision-makers by the individuals attempting to implement the decision.48

In fact, the Bureaucratic Politics Model sees no unitary actor leading the organization, accepts no over-arching vision or all-encompassing strategic direction, but, rather, considers many ‘game’ players who focus, not upon a single common unifying strategic issue, but upon many diverse, personal interests and goals.49 Arguably, when such a model becomes engrained in any organization – military, academic, or otherwise – the result is the disheartening fact that professionals will “...find themselves functioning as employees in a growing bureaucratic organization,” where ad hoc strategic-making, individualism, self- interests, and acts of career protection dominate their professional realm.50

In sum, CF transformational leadership must be cognizant of this individualistic power and put in place viable organizational culture strategies to offset individual interests that may be contrary to the profession’s health.51 The main issue current transformational CF leaders must resolve is the proper degree of power and control required in the CF between the individual member, the professional institution, and the military’s bureaucratic diarchic structure.52 Arguably, transformational success will depend upon leadership and the strategic decision-making tools leaders use to ensure a professional military in Canada. Ultimately, “...the history of the military profession ... becomes the history of a dialetic tension between hierarchical and professional poles of the professional in uniform.”53

The rising individualistic nature existing within the Canadian work force – and its inherent tendency for careerism and self-protectionism – will only exacerbate the problem of bureaucratic strategic decision-making that historically has dominated the ‘profession of arms’ in Canada.

Generalist-Specialist Dichotomy

The generalist-specialist dichotomy is concerned with that fundamental tenet of all professions – ‘expertise.’54 As expressed by sociologist Talcott Parsons, a traditional view of such expertise is: “The ideal professional man is not only a technical expert in the sense of transcending special skills; by virtue of his mastery of a great tradition he is a liberally educated man, that is, a man of general education.”55

In contemporary military terms, military leadership is concerned with two thoughts: 1) determining the content and level of knowledge a military professional needs to fulfill his/her duty to society throughout a military career; and 2) determining the best way to deliver such knowledge. The resulting differences are explained in terms of ‘education’ and ‘training.’ There is a general understanding that education is intended to develop military professionals who can create “...a reasoned response to an unpredictable situation,” while their training is intended to allow them to give “...a predictable response to a predictable situation.”56

These terms are not to be trivialized, for military officers and theorists have, throughout history, viewed the education and training of a military professional as “...among the most important activities engaged in by armed forces around the world.”57 Such importance is heightened further by the volatile nature of the 21st Century, for “...never before have academics played so great a role in the formation of military officers, and never before have academic subjects played so great a part in the military curriculum.”58

Huntington’s writings give contextual substance to this educational-training dilemma. In proclaiming the benefits of military education, he argued:

The military skill requires a broad background of general culture for its mastery... [The military professional] cannot really develop his analytical skill, insight, imagination, and judgement if he is trained simply in vocational duties. The abilities and habits of mind which he requires within his professional field can in large part be acquired only through the broader avenues of learning outside his profession... Just as a general education has become the prerequisite for entry into the profession of law and medicine, it is now almost universally recognized as a desirable qualification for the professional officer.59

In 1980, the renowned military specialist and author, Richard A. Preston, in a lecture to the United States Air Force Academy, explained the opposing positions of the educational-training gap.60 He offered that advocates of military training hold that an emphasis on training produces a soldier with greater dedication, decisiveness, loyalty, leadership, and technical proficiency. He also pointed out that, in contrast, supporters emphasizing education over training held that education produces a creative soldier who can think independently. This point is disregarded by the training proponents, who point out that education of the individual soldier “...disperses effort into often unnecessary and irrelevant intellectual pursuits, fosters questioning and diffidence, and endangers the essential homogeneity of a disciplined force.”61 Such a position is supported further by military historian Martin van Crevald who stated that warfighting ability “...cannot be acquired by sitting behind a university desk.”62

Conversely, proponents of the education position argue that military professionals are more than just ‘warfighters’; they are ‘managers of violence.’ They purport that it is only through education that they will be able to understand that fact and all that it entails.63 It is through education that a military professional will attain the degree of expert knowledge deemed “essential to the vitality and lifeblood” of a contemporary military.64

Military analysts John Nagl and Paul Yingling, in Snider’s treatise on US Army professionalism, have also articulated the education-training dilemma. They argued: “The officer as warrior is duty-bound to educate himself in the theory and practice of war. Such an education trains an officer not what to think but how to think.”65 For them, military education develops officers with ‘creative intelligence,’ allowing officers to know when to adhere to rules and conventions and “...when to disregard them and attempt the unconventional.”66 Conversely, “...the officer who studies theory at the expense of practice becomes guilty of... military scholasticism,” while soldiers on a battlefield become sacrificial pawns acting out some distant game of chess.67 In reverse, an experienced officer who is “...uninformed by theory and blind to innovation” becomes a ‘mule,’ unable to learn from combat experience alone.68

DND photo AR2007-Z039-3 by Corporal Simon Duchesne, JTF Afg – TF – Image Tech

Members of the Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) discuss community needs with Afghanis during a recent patrol to the village of Khuajev molk.

One Canadian military perspective is that a military education is attributed to the existence of the university itself. For example, at “...the heart of intellectual honesty and criticism, through six centuries of religious dogma, political fashion, and professional strictures has been the university.”69 Furthermore, there is a general understanding that while military universities produce men and women, “...imbued with leadership and a desire to serve,” they also produce ‘good citizens,’ who contribute to Canadian society.70

Arguably, what must be avoided at all costs is the tendency to change military universities (such as the Royal Military College of Canada [RMC]) into training schools, because military education ensures the ongoing communication of knowledge and military expertise throughout the military’s existence. In essence, it grounds the organization’s desired culture.71 Furthermore, as military scholar, then-Major (now Lieutenant- Colonel [ret’d]) David Last proclaimed:

The classes change each year, because knowledge is never static. Students know that they are learning, because they have more questions at the end than at the beginning of a course, but they have a good idea about how to look for answers to these questions. This is education. When a subject expert... cannot explain how or why something is known, then we have lost the essence of the questioning university. Pedagogy (the art of teaching) without epistemology (the philosophy of knowledge) degenerates quickly into pedantry (insistence on forms and details).72

Other Canadian military perspectives address the historical misnomer that education for military personnel is unnecessary by noting that “...this attitude [is] rooted in a complete ignorance of the importance of education to the military profession.”73 Further: “In the complex world of today and tomorrow... the officer’s understanding must match that of society – otherwise he or she cannot serve it.”74

As the above synopsis offers, the basis of the education-training dilemma is that a military professional is distinguished from all other professionals, civilian bureaucratic professionals, academics, and everyone else, by the requirement for its members to have ‘expert’ knowledge in the application of force. For military personnel operating in the 21st Century – including CF members – such knowledge, at a minimum, encompasses the intellectually understanding of the intricacies of military organizations, technology, morality, ethics, human development, national politics, international relations, and culture(s).75 Conjointly, in such a complex environment, those same individuals must have the skills, training, and experience to apply appropriate military force accurately as mandated by government.

Conclusion

Arguably, the transformation of the CF organizational culture is completely dependent upon CF leadership effectively working within the above-noted civil-military relationship. The trick is finding the right balance while enduring an extremely high operational tempo, a series of minority federal governments, and a hesitant Canadian public. With the goal of obtaining optimal military effectiveness, the challenge facing CF leadership today is to balance the above-mentioned contrasting themes equitably while communicating and interacting with all Canadians. This is a very worthy challenge, indeed.

![]()

Pamela Stewart has a Master’s degree in Strategic Studies from the University of Calgary. She has practised briefly as a Legal Aid lawyer and has eight years of combined service in the Communications Branch and the Naval Reserve. Her interests include civil military relations, military professionalism, and ethics, and her Master’s thesis was entitled, “Professionally Disconnected: Human Resources Strategic Planning in the Canadian Forces.”

Notes

- The Department of National Defence (DND), the Canadian Forces (CF), and the organizations and agencies that collectively make up the National Defence portfolio for Canada are collectively referred to as Defence. As per the National Defence Act [RS, 1985, c. N-5], the DM is responsible for policy, resources, and international defence relations. Via ministerially delegated authority, he/she exercises overall management and direction of DND. The CDS has primary responsibility for command, control, and administration of the CF along with military strategy, plans, and requirements. The CDS, as senior military advisor, has direct access to the Prime Minister and Cabinet regarding all major military concerns and operations. This delineation of authority is the basis for the NDHQ diarchical structure.

- Canada, Department of National Defence, Canada’s International Policy Statement: A Role of Pride and Influence in the World – Defence (Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2005), pp. 2, 11-12, 17, and 32. [Hereinafter DPS)].

- Canada, Department of National Defence, “Canadian Forces Begin Transformation: Commander of Canada Command and Stand-Up Date Announced,” in News Release NR-05.052 (28 June 2005), at <http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/newsroom/view_ news_e.asp?id=1691> (1 December 2005); Canada, Department of National Defence, The Chief of the Defence Staff, CDS Planning Guidance-CDS Action Teams, (10 March 2005), p. 1/4.

- DPS, 1-4. For the CDS’ position see CAT 1 ‘Executive Summary’, Point 18, <www.cds.forcs.gc.ca/cft-tfc/00native/CAT% 201%20Exec%20 Sum%20Eng.pdf> (1 February 2006), and for an explanation of “integrated,” see CAT 2 ‘Executive Summary’, Ex.3 and Ex.4, at <www.cds.forces.gc.ca/cft-tfc/pubs/cat_e.asp> (1 February 2006). The term ‘command centric’ entails “commanders being accountable for clearly defined authorities and responsibilities. They will also fully understand their commander’s intent and will have an operational focus dedicated to achieving the goal.” Captain Vance White, Public Affairs Officer for CF Transformation, “The Strategic Command Construct,” The Maple Leaf, Vol. 8: No. 38, (2 November 2005) ,at <http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/community/mapleleaf/index_e.asp? newsID=2024> (13 May 2006).

- For example, see Canada, Securing in Open Society: Canada’s National Security Policy (Ottawa: National Library of Canada, 2004), p. vii.

- Hubert Saint-Onge and Charles Armstrong, The Conductive Organization: Building Beyond Sustainability (London: Elsevier Inc., 2004), p. 1.

- Ibid.

- Colonel Richard D. Hooker, Jr. “Soldiers of the State: Reconsidering American Civil-Military Relations,” Parameters, Vol.33, Issue 4, (Winter 2003-2004), pp. 4-18.

- Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1959), p. 7. For a further explanations, see Peter D. Feaver, “The Civil-Military Problematique: Huntington, Janowitz, and the Question of Civilian Control,” in Armed Forces & Society, Vol 23, No. 2, (Winter 1996), throughout; and, Samuel P. Huntington, “The Military Mind: Conservative Realism of the Professional Military Ethic,” in War, Morality, and the Military Profession, Malham M. Wakin (ed.) (Boulder, CO: Westview Press Inc., 1979), pp. 29, 25-49.

- Christina V. Balis, “Reluctant Warriors? European Army Professionalism in Transition,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 2005), p. 6.

- Morris Janowitz, “The Future of the Military Profession,” in War, Morality, and the Military Profession, pp. 53, 51-77

- Ibid.

- Todd S. Sechser, “Are Soldier’s Less War Prone Than Statesmen?,” in Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 48, No. 5, (October 2004), pp. 746-747. For a similar analysis on the traditional model of Western military professionalism, see Allan English, “The Senior NCO Corps and Professionalism: Where Do We Stand?” in A Paper Prepared for the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute (4 Feb 2005), at <http://www.cda-acd.forces.gc.ca/CFLI/engraph/research/pdf/87.pdf> (10 June 2005).

- Sechser, p. 771.

- Ibid., pp. 747, 750, 763, and 765. For a detailed explanation of Huntington’s position on ‘military conservatism,’ see Feaver, “The Civil-Military Problematique,” pp. 149-178.

- Sechser, p. 771.

- Feaver, “The Civil-Military Problematique”, p. 149.

- Karol W. J. Wenek, Project Director CF Leadership Doctrine, “Looking Back: Canadian Forces Leadership Problems and Challenges Identified in Recent Reports and Studies,” in A Paper Prepared For the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, (Kingston: Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, June 2002), at <http://www.cda-acd.forces.gc.ca/CFLI/ engraph/research/pdf/73.pdf> (10 January 2006).

- For such a contrasting argument based upon ‘agency’ theory, see Peter D. Feaver, “An Agency Theory Explanation of American Civil-Military Relations During the Cold War,” in Working Paper For the Program For the Study In Democracy, Institutions, and Political Economy, (5 November 1997), at <http://www.poli.duke.edu/dipe/Feaver1.pdf> (10 June 2006).

- Balis, pp. 13-19. For examples, see the following throughout: Andrew Abbot, The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988); Eliot Freidson, Professionalism Reborn: Theory, Prophecy and Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State; Morris Janowitz, The Professional Soldier (Glencoe: The Free Press, 1960); War, Morality, and the Military Profession, Malham M. Wakin (ed.) (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1979); and General Sir John Hackett, The Profession of Arms (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1983).

- See Bernard Barber, “Some Problems in the Sociology of Professions,” Daedalus Vol. 92, No. 4, (1963), p. 672, as quoted in Balis, “Reluctant Warriors?”, Footnote 12, p.16.

- Huntington, The Soldier and the State, pp. 8-18.

- Doctor J.L. Granatstein, “Military Education,” Presentation at the Conference of Defence Associations 1st Annual Graduate Student Symposium (13-14 November 1998), at <http://cda-cdai.ca/ symposia/1998/98granats.htm> (11 August 2006).

- See Feaver, “The Civil-Military Problematique.”

- James Burk, “Expertise, Jurisdiction, and Legitimization,” in The Future of the Army Profession, Revised and Expanded, 2nd Edition, by Lloyd Matthews (Boston: McGraw-Hill Custom Publishing, 2005), pp. 43-44.

- Balis, pp. 24-51.

- For a detailed analysis of Max Weber’s bureaucratic ideas and their relationship to military professionalism, see Lieutenant-Colonel Bill Bentley, Professional Ideology and The Profession of Arms in Canada (Toronto: The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies, 2005), pp. 20, 53-58; and, Max Weber, Economy and Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), throughout.

- Balis, p. 41.

- Ibid., p. 24.

- Huntington, The Soldier and the State, p. 16.

- Harries-Jenkins, “The Concept of Military Professionalism,” pp. 124, 127, as quoted by Balis, Footnote 118, p. 45.

- Balis, p. 62.

- Canada. National Defence, Duty With Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada, (Ottawa-Kingston: Published under the auspices of the Chief of the Defence Staff by the Canadian Defence Academy- Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, 2003), p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- Andrew Abbot, The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labour, as quoted by Balis, Footnote 20, p. 18. The Charles Moskos-Morris Janowitz’ institutional/occupational debates of the 1970s and 1980s present similar ideas. For further study, begin with Charles C. Moskos, “The All Volunteer Military: Calling, Profession, or Occupation,” Parameters Vol. 7, No.1, (1977), pp. 5-7; The Military: More Than Just a Job?, Charles C. Moskos and Frank R. Wood (eds.) (Washington: Pergamon Brassey’s, 1988); and Morris |Janowitz, “From Institutional to Occupational: The Need for Conceptual Clarity,” Armed Forces & Society Vol. 4, No.1, (Summer 1994), pp. 599-617.

- Lloyd Mathews (ed.), The Future of the Army Profession, 1st Edition (Boston: McGraw-Hill Publishing, 2002), Chapter 25, as quoted by Bentley, Footnote 47, p. 36.

- Ibid., and Leonard Wong and Don M. Snider, “Strategic Leadership of the Army Profession,” in The Future of the Army Profession, Revised and Expanded, 2nd Edition, Lloyd J. Matthews (ed.) (Boston: McGraw-Hill Custom Publishing, 2005), p. 601.

- For a detailed table comparing the concepts of Profession vs. Bureaucracy, see Don M. Snider, “The U.S. Army as Profession,” in The Future of the Army Profession, Revised and Expanded, 2nd Edition, p. 14.

- Balis, p. 96.

- Don M. Snider, “The U.S. Army as Profession,” p.15.

- Ibid.

- Balis, p. 73.

- N. Fotion and G. Elfstrom, Military Ethics: Guidelines for Peace and War (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 90.

- Beverly Kaye, Devon Scheef, And Diane Thielfoldt, “Engaging the Generations,” in Human Resources in the 21st Century, Marc Effron, Robert Gandossy, and Marshall Goldsmith (eds.) (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2003), p. 25.

- Ibid., pp. 27-30.

- Graham T. Allison and Philip Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2nd Edition (Reihe: Longman, 1999), throughout.

- Edward Rhodes, “Do Bureaucratic Politics Matter?: Some Disconfirming Findings From the Case of the US Navy,” World Politics, Vol. 47, No. 1, (October 1994), at <www.jstor.org> (10 August 2005).

- As surmised by J. Garry Clifford, “Bureaucratic Politics,” The Journal of American History, Vol. l77, No. 1, (Jun 1990), at <www.jstor.org> (10 August 2005).

- Ibid.

- Allison, Essence of Decision, p. 144.

- William L. Zwerman, Susan Raydt, and Janice Thomas, “Professionalization in the Canadian Armed Forces: Bureaucracy, Inclusiveness, and Independence”, in A Paper Prepared for the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, (31 March 2003), at <http://www.cdaacd.forces.gc.ca/CFLI/engraph/research/pdf/56.pdf>

- For a detailed explanation of transfor- mational leadership, see the CF publication, Leadership in the Canadian Forces: Conceptual Foundations, Footnote 4.

- Zwerman, Raydt, and Thomas, “Professionalization in the Canadian Armed Forces: Bureaucracy, Inclusiveness, and Independence.”

- G. Dearborn Spindler, “The Military-A Systematic Analysis,” Social Forces, Vol. 27, No.1, (October 1948-May 1949), pp. 83-88, as quoted by Balis, Footnote 122, p. 46.

- For a thorough explanation regarding the generalist/specialist dichotomy, see Balis, pp. 48-51.

- Talcott Parsons, “Remarks on Education and Professions,” in International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 47, No. 3, (April 1937), p. 366, as quoted by Balis, Footnote 132, p. 48.

- Last, “Educating Officers: Post-Modern Professionals To Control and Prevent Violence,” pp. 26-27; and Doctor Ronald G. Haycock, “The Labours of Athena and the Muses: Historical and Contemporary Aspects of Canadian Military Education,” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, (Summer 2001), p. 8.

- Elliott V. Converse III, “Introduction,” in Forging the Sword: Selecting, Educating, and Training Cadets and Junior Officers in the Modern World, Elliot V. Converse III (ed.) (Chicago: Imprint Publications, 1998), p. 1. See Footnote 1.

- Doctor Jim Barrett, Director, Directorate Learning Management, Canadian Defence Academy, “Integration of Civilian and Military Education,” 2005 Conference Proceedings, Expanding and Enhancing the Partnerships – Further Steps After Istanbul, at <www.pfpconsortium.org.>

- Huntington, The Soldier and the State, p. 14.

- Richard A. Preston, “Perspectives in the History of Military Education and Professionalism,” in The Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History, Number Twenty-Two, (Colorado Springs, Colorado: United States Air Force Academy, 1980), p. 8.

- Ibid.

- Martin van Creveld, The Training of Officers: From Military Professionalism to Irrelevance (New York: The Free Press, 1990), p. 77.

- Last, “Educating Officers: Post Modern Professionals to Control and Prevent Violence,” p. 26; and Huntington, The Soldier and the State, p. 11.

- Henry H. Shelton, “Professional Education: The Key to Transformation,” in Parameters, Vol. 31, Issue 3, (Fall 2001).

- John Nagl and Paul Yingling, “The Army Officer as Warrior,” in The Future of the Army Profession, Revised and Expanded, 2nd Edition, p. 148.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Abraham Flexner, Universities: American, English and German (London: Oxford University Press, 1930/1968), as quoted by Lieutenant-Colonel David Last, “Military Degrees: How High is the Bar and Where’s the Beef?” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2, (Summer 2004), Footnote 2, p. 30.

- Last, “Military Degrees: How High is the Bar and Where’s the Beef?”, p. 30.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp. 30-31.

- Lieutenant-Colonel Bernd Horn, “Soldier/Scholar: An Irreconcilable Divide?”, in The Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin, Vol. 4, No. 4, (Winter 2001-2002), p. 4.

- Major David Last, “Educating Officers: Post Modern Professionals to Control and Prevent Violence,” in Contemporary Issues in Officership: A Canadian Perspective, Lieutenant-Colonel Bernd Horn (ed.) (Toronto: Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies, 2000), p. 26.

- For a further explanation of these terms, see Don. M. Snider, “The U.S. Army as Profession,” pp. 12-14.

University of Calgary

Centre for Military and Strategic Studies sponsors:

Forced to Change: Education and Reform 10 Years After

Fairmont Palliser Hotel Calgary, Alberta 30 January – 1 February 2008

Registration fee: $250.00, $100.00 students

Conference information visit:

http://www.cmss.ucalgary.ca/conference-workshop/forcedchange

Further information, contact Nancy Pearson Mackie:

CMSS Events Coordinator Phone: (403) 220-4030 or njmackie@ucalgary.ca