This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Lessons From the Past

CMJ Collection

Soldiers of the Brigade of Gurkhas on exercise in a rubber estate in Malaysia. This is familiar territory for these indigenous troops, who served in the area with the British for over 20 years.

Historical Lessons from the British and Germans: The Case for Integrated Indigenous Forces as a Logical Force Multiplier

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

This aim of this article is to demonstrate through example how the employment of integrated indigenous forces within the British and German armies in past counterinsurgency (COIN) operations substantially increased the quality and quantity of local intelligence, extended their pacification capabilities, and leveraged an untapped manpower pool to provide resources to conduct economy of force operations. The British and German historical experiences show that indigenous forces integrated within their force structures produced better intelligence and operational performance than purely local government forces with advisors. These historical experiences of utilizing indigenous forces to augment intelligence capabilities and manpower allow the militaries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to glean potential ideas for use in their pacification duties in Iraq, Afghanistan, and future battlefields.1

The British Experience

The Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) is a worldwide counterinsurgency campaign that makes it an intelligence and special operations intensive war. This type of operation also means increased manpower requirements to secure populations threatened by insurgent activity. As the draft U.S. Army Field Manual entitled Counterinsurgency states:

Without good intelligence, a counterinsurgent is like a blind boxer, wasting energy flailing at an unseen opponent and perhaps causing unintended harm. With good intelligence, a counterinsurgent is like a surgeon, cutting out cancerous tissue while keeping other vital organs intact. Effective operations are shaped by carefully considered actionable intelligence, gathered and analyzed at the lowest possible levels and disseminated and distributed throughout the force.2

The British and broader Commonwealth usage of integrated indigenous forces, particularly formations of captured insurgents or tribal irregulars led by a counterinsurgent cadre, enhanced their intelligence architecture while simultaneously augmenting their manpower base. This approach merits reviewing for current relevance.

The British have employed indigenous forces in counterinsurgencies effectively during the 20th Century and earlier. They generally have done a better job than the United States and other nations of codifying small-wars experiences and principles, and then applying them in subsequent conflicts.3 Britain’s experience in its use of indigenous troops for counterinsurgency dates back at least to the 18th Century, when it employed Indian tribes in the French and Indian War, and later, in the American War of Independence. This legacy was remembered within the British army and its Commonwealth descendants throughout the 19th Century and into the post-Second World War period. The postwar United Kingdom raised a number of indigenous soldiers and tribally based irregulars, officered by a British cadre, to augment its regular forces engaged in a myriad of counterinsurgencies.

In particular, and perhaps uniquely, the use of ‘turned’ (turncoat) insurgents became a prominent characteristic of British practice in stability operations. Groups of former insurgents, known as ‘pseudo-gangs,’ offered essential knowledge, not only of the local people, terrain, culture, and language, but also of the mind-set of the insurgent – they had grasped and could exploit his organization, psychology, and tactics. This source of intelligence is an important component within an overall organizational blueprint for proactive collection.

CMJ Collection

Gurkhas deplaning from a British helicopter in a jungle clearing.

Malaya and Indigenous Tribesmen

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the United Kingdom attempted to re-exert control over a number of its colonial possessions. In Malaya, local power politics had changed, presenting challenges to British rule. By early 1950, Malayan communists were conducting a destabilizing terrorist campaign from jungle bases. During what became known as the Malayan Emergency, European soldiers were, at first, unskilled in the ways of the jungle. To overcome this handicap, the British imported from nearby North Borneo and Sarawak a number of Dyak tribesmen, and used them as trackers and scouts. These men were headhunters, and they could read trail signs, such as bent twigs and shifted leaves, that were meaningless to Europeans. Other jungle tribes also had been much exploited by the communists during the Japanese occupation and the early stages of the emergency, and they became willing allies when contacted by the British government. Jungle forts and short airstrips facilitated their logistical support. These irregulars proved a powerful way for government forces to avoid being ambushed, and to close with and destroy insurgents. Further, their close- combat skills were remarkable. For example, the Senoi Pr’ak tribesmen, numbering not more than 300, many of whom were armed only with traditional blowpipes, managed to kill more insurgents in the last two years of the emergency than the rest of the security forces combined.4

The best guides, however, were ex-guerrillas, who often led patrols into jungle camps with which they were familiar. With the exception of a very few ‘hardcore’ communists, whom the government executed, banished, or imprisoned, guerrillas who surrendered were rehabilitated in special training schools. The majority of these men – known as “surrendered enemy personnel” (SEPs) or “captured enemy personnel” (CEPs) – had become involved in the communist movement by force of circumstance, rather than through political conviction. Many SEPs joined the government’s Special Operational Volunteer Force, where they received the pay of a junior policeman and they participated in patrols against their former comrades in the jungle. After some 18 months’ service, SEPs generally were released unconditionally to civilian life. The SEPs proved invaluable to the government, both as sources of intelligence and as agents of psychological warfare. These followed prototypical experiences that had been developed by the British during the Mau Mau revolt in Kenya, which lasted from 1952 until 1960. There, captured insurgents were used extensively in “counter-gangs,” initially groups of loyal blacks led by white officers and noncommissioned officers who went into the forests posing as Mau Mau gangs in an attempt to make contact with and to eliminate genuine gangs. Many surrendered rebels willingly cooperated and were incorporated into counterinsurgent operations. This incorporation into British units increased intelligence collection on the insurgents, and it expedited their destruction. This model reached its apogee, however, not in Malaya, but during the Rhodesian counterinsurgency campaign, which will be covered shortly.5

On the manpower front, requirements for Malaya were largely driven by the Briggs Plan – a systematic approach designed to provide security for the rural population while simultaneously removing the sources of terrorist supply, food, and recruitment. In order to implement this plan, the British depended upon extensive indigenous support for their counterinsurgency efforts. The British force package in Malaya consisted of three major components: a rotating group of regular British Army battalions, battalions and smaller units from the British Commonwealth (including Malayan units), and a large force of eight Gurkha infantry battalions deployed for the duration of the conflict.6 These latter units are most germane for the discussion of integrated indigenous forces. The Gurkha battalions were recruited from a number of fierce tribal groups in Nepal, and British and Gurkha officers commanded them. They were long-serving soldiers fully integrated into the British command structure, and these formations provided the cornerstone of the manpower base for the Malayan counterinsurgency.

CMJ Collection

ZANU guerrillas in Rhodesia displaying a variety of Eastern Bloc weaponry.

Rhodesia and the Selous Scouts

The insurgency in the former British colony of Rhodesia started out in the 1960s at a low, seemingly containable level, but, by 1973, the complexion of the war had changed. Soon, insurgent activity so intensified that a total commitment of security forces was required. Ultimately, the breakaway white-minority government in Salisbury faced, notwithstanding the political and naval opposition of the British, two major insurgent groups – the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, together with its military arm, the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA); and the Zimbabwe African National Union, with its military wing, the Zimbabwe National Liberation Army (ZANLA). The two elements were largely tribally based, and their respective armed components used very different strategies. ZIPRA focused on conventional Soviet- style operations, while ZANLA operated under a Maoist rural strategy. The groups did not cooperate; in fact, there were clashes between them.7

The Rhodesian army initially was able to isolate the war near the northern border with Zambia. However, as it became apparent that the Portuguese were failing to contain anti-colonial campaigns in Mozambique, (Mozambique was to become independent of Portugal in 1975), to the east and north, support and sanctuary for Rhodesian terrorists began to spread into that colony. This expansion, combined with growth and better training of the insurgents, resulted in several guerrilla successes during 1973. The fighting resulted in very few white casualties – the primary victims being blacks who worked the European-owned farms. In fact, there is little evidence that the majority of the Rhodesian black population supported the nationalist cause, but neither did it enthusiastically support the white minority government. Brutalization of black tribesmen by insurgents may have increased sympathy for the white-minority government, but it also undermined confidence in that government’s ability to protect those at risk.

From 1973 until 1975, both sides began to learn unconventional warfare. The guerrillas demonstrated the discipline required to wage an effective campaign for the ‘hearts and minds’ of the populace. The Rhodesian security forces, for their part, developed counterinsurgency methods that would bring, at least, tactical success, and, in later years, these methods would be studied abroad.8 Because they were no more numerous than the insurgents, the Rhodesian security forces had to rely upon small-unit operations, innovative tactics and techniques, and special operations. The Rhodesian army eventually seized on the concept of ‘pseudo’ forces, after some bureaucratic resistance. It needed troops who could pose as insurgents among the local population, and could even deceive the enemy. The tasks of the pseudo-gangs were to gather intelligence, locate insurgent groups, and, when the time was propitious, eliminate their leaders. Also, they could simply stir things up for the nationalists by pitting one group against the other.

The result was the formation of the Selous Scouts (pronounced “Sel-oo,” named after Frederick Courtney Selous, Rhodesia’s most famous big-game hunter),9 a predominantly black unit that conducted a highly successful clandestine war by posing as guerrillas and fighting as they did. The Scouts’ skills soon extended beyond tactical intelligence-gathering to direct attacks upon the insurgents and their leaders, without regard to international borders. Their tracking, survival, recon-naissance, and counterinsurgency techniques made them one of the most feared and despised (by the terrorists) units of the Rhodesian army.10

As the British had done in Malaya and Kenya, the Scouts ‘turned’ captured insurgents for use against their former comrades – and they did so with particular skill and aplomb. Guerrillas captured in an engagement would be invited to change sides in return for good treatment; an insurgent who had already switched sides would inform the captive of his alternatives – death at the gallows or a chance for redemption in service for the government. Those who chose the latter had to convince their new comrades of their good faith.11

The Selous Scouts would deploy a team of four to 10 men into an operational area, from which all other friendly forces would be withdrawn. The team posed as a guerrilla force down to the last detail, dressing in insurgent uniforms and carrying communist weapons – but, critically, they were much better trained and better disciplined. The local populace, thinking the Scouts were insurgents, might well inform them about genuine insurgents in the area. Detecting an insurgent force, the Selous Scouts would begin to stalk it, remaining undetected themselves until they chose to make contact. The Selous Scouts, in this way, carried the war directly to the guerrillas, thereby allowing civil-action and police measures to be extended into heretofore- lost zones.12

Although its larger political cause ultimately failed, with Rhodesia becoming the independent, black-majority state of Zimbabwe in 1980, the professional reputation of the Rhodesian security force as a whole was solid. Even within that service, however, the Selous Scouts were extraordinary. During the war, they were credited with the deaths of 68 percent of the insurgents killed within the borders of Rhodesia. Their example points to an essential component of an effective counterinsurgency campaign – using indigenous forces with knowledge of the terrain, culture, and enemy to outfight the guerrilla within his own paradigm. The Selous Scouts were simply better at guerrilla warfare than the guerrillas themselves.13 The unique intelligence asset that was embodied in ‘turned’ insurgents that had been incorporated within the regular Rhodesian army force structure drove their successful operations.

The German Experience

The German experience during the Second World War with respect to its occupied territories illustrates that the vast and necessary resources expended for security by counterinsurgent/ anti-partisan forces always dwarf those of their opponents, and successful COIN often requires a very high force ratio. That is a major reason why protracted wars are hard for a counterinsurgent to sustain. The scale and complexity of COIN should never be underestimated.14 Despite having allies, the German army of the Second World War faced severe manpower constraints throughout Europe and North Africa once the invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa, was launched during the summer of 1941. In addition to fighting a conventional war against the Allies in all theatres of operations, the German army also had to contend with irregular warfare against partisans and guerrillas on the Eastern Front, and in large parts of Southeast Europe, particularly Yugoslavia. German units, often bearing the brunt of the anti-guerrilla effort, had a number of difficulties, chief amongst which was a shortage of personnel.15 It is not known exactly when and where the first units of volunteers from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and from the countries annexed by the Soviet Union after 1939, were organized to fight against the Soviets on the German side. Nevertheless, somewhere in the neighbourhood of one million foreign volunteers eventually ended up serving in the German army. The Germans had two categories of indigenous troops that pertain to this article – the Ostbataillonen (Eastern Battalions) and the Ostlegionen (Eastern Legions).

Ostbataillonen

The overall category of troops employed on the Eastern Front was the so-called Osttruppen (eastern troops), which included all volunteer personnel integrated in formed units into the German forces. They were clad in German uniforms and designed to guard communication lines, fight Soviet partisans in the rear of the German armies, and, sometimes, even to hold less important sectors of the front. They were normally grouped in battalions termed Ostbataillonen, and they seldom exceeded battalion size. These Ostbataillonen were allocated to and fitted within German regiments and divisions. The first units were organized initially on the basis of private enterprise by German unit commanders in defiance of official orders. The bulk of them were recruited from non-Russian nationalities – Balts, Ukrainians, Caucasians, and Cossacks. These arrangements soon became more formalized, and, in November 1941, Army Group Centre organized the first six battalions to operate in its rear area.16 On 15 December 1942, the Inspectorate of Eastern Troops was established to supervise the proliferating number of indigenous units. Each unit was subordinated to a German unit, located either in the front line or in the rear areas. Each headquarters of a numbered German Army or Army Group in Russia included a headquarters staff for Eastern troops.17

By autumn 1943, opponents of the Ostbataillonen tried to have them disbanded, but the Inspectorate of Eastern Troops was able to demonstrate that there were at least 427,000 Eastern volunteers – equal to some 30 German divisions, and a force no sane person would disband, given the Wehrmacht’s manpower shortage. Due to political considerations, these volunteers were sent to the occupied countries of Western and Southern Europe for security duties.18

The ultimate contribution of the Ostbataillonen to German manpower deficits is hard to quantify, given imperfect data, but their ability to take pressure off main force Wehrmacht units, and to perform security duties, is unquestioned. According to a possibly incomplete German list of June 1943, there were already 68 battalions, one regiment, and 122 companies of these assets in service at that date. An American list of 1945 documents 180 Ostbataillonen in German service.19 Regardless of the actual numbers, these integrated indigenous units expanded the overall capacity of the German Army to conduct pacification and anti-partisan operations.

Ostlegionen

The next step in the development of the German army’s use of indigenous troops was the creation of the Ostlegionen (Eastern Legions). At the end of 1941, an order created several such formations. Since the first volunteers to become regular members of the German army came from the Asiatic and Caucasian peoples of the USSR, who viewed the Germans as liberators of their homelands, the Supreme Command ordered the formation of several volunteer legions from these nationalities on 30 December 1941. The army then raised these units during the first half of 1942.20 This top secret memorandum ordered that the Supreme Command was to create: first, the Turkistani Legion from volunteers of the following nationalities – Turkomans, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Kirghiz, Karakalpaks, and Tadjiks; second, the Caucasian-Mohammedan Legion, from Azerbaijanis, Daghestans, Ingushes, Lezghins, and Chechens; third, the Georgian Legion; and fourth, the Armenian Legion.21 The Ostlegionen were given a status identical to that of the European volunteer legions. In all, the number of volunteers to serve in the Eastern Legions must have totalled around 175,000 personnel.22 According to the testimony of Caucasian leaders, the number of volunteers from the Caucasus alone who fought on the German side was 102,300 men.23

In contrast to the unofficial formations, the Eastern Legions had national committees from the start. It must be explained that a ‘legion’ was not a tactical formation. Rather, it was a training centre where national units, mostly battalions, were organized and trained.24 Most of these legions were used in anti-partisan operations in Russia, and, later, in Yugoslavia.

Besides partisan warfare on the Eastern Front and in the Balkans, from 1941 until 1944, the German occupation forces were engaged in a protracted attempt to destroy an elusive guerrilla enemy.25 Given the manpower constraints imposed by the Eastern Front, the German army used a mix of indigenous troops from puppet regimes, Waffen SS foreign units, and integrated indigenous units – with varying degrees of success – to pacify this secondary theatre of war. The Ostlegionen were deployed as part of the integrated indigenous units.

One of the most distinguished counterinsurgency formations in the Balkan theatre was the Turkistani Legion. The Legion was formed in the spring of 1942 as part of the German 162nd Infantry Division, being referred to as the “Turkoman Infantry Division.” It appears that it was the largest of all the Ostlegionen formations, and it saw extensive action in Yugoslavia and Italy.26 It was composed of Germans, Turkomans, and Azerbaijanis, and, according to its commander, it was as good as a normal German division.27

The mutual advantages of the Ostbataillonen and Ostlegionen arrangements are obvious. German officers commanded these Eastern Legions, and they included a cadre of non-commissioned officers and specialists. This integrative approach strengthened the fighting qualities of the unit, and it enhanced the level of military professionalism among the indigenous ranks. The Eastern volunteers provided manpower that could not be ‘tapped’ from German national sources; the formations were less costly to create and maintain; and, they enabled the German army, which provided a small investment in training, outfitting, and leading these units, to free up its more valuable and proficient combat units from anti-partisan and security duties, and to use them in the Eastern and Western theatres for combat duties.

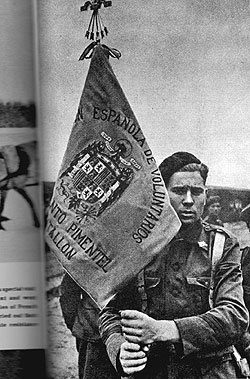

CMJ Collection

A Spanish volunteer of the Blue Division in service with the Germans on the Eastern Front.

Lessons Learned

The British use of integrated indigenous forces provides instructive lessons for improving intelligence capabilities in a counterinsurgency, and the aforementioned German army experience demonstrates how integrated indigenous volunteers can be used to alleviate manpower shortages. The British in Malaya used innovation very effectively by importing Dyak tribesmen as trackers and scouts. More saliently, many ex-guerrillas proved their worth to the government as intelligence sources, psychological warfare agents, and counterinsurgent forces. Second, in Rhodesia, the security forces employed ‘pseudo-gangs’ to gather intelligence, to locate insurgent groups, and to eliminate leaders. The predominantly black Selous Scouts became a particularly lethal counterinsurgency instrument, and they achieved extraordinary results. More usefully, the effectiveness of specialized teams and operations to eliminate insurgent leadership and – infrastructure – the Rhodesian Selous Scouts – points to the potential utility of this model on the Afghan/Pakistani border, and in Iraq.

One possibility for the relevant NATO armies would be the development and use of pseudo-formations, based upon the British and Rhodesian models. Because of the dispersed nature of COIN, counterinsurgency operations are a key generator of intelligence. A cycle develops whereby operations produce intelligence that drives subsequent operations. Tactical reporting by units, members of a national team, and associated civilian agencies are of equal or greater importance than reporting done by specialized intelligence assets. These factors, along with the need to generate a superior tempo, drive the requirement to produce and disseminate intelligence at the lowest practical level.28 Pseudo units and their operations catalyze this self-feeding cycle. To initiate such a ‘pseudo-gang’ project, there still exists a body of expertise and knowledge from Malaya, Kenya, and Rhodesia that is available and could be tasked to experiment with this concept.

The British and German cases also illustrate how certain ethnic minorities can be used effectively as local troops integrated within an established force structure. The German experience, in particular, is instructive in that fully integrated indigenous troops with German cadres within the Wehrmacht generally performed better than national troops, and they were able to make up for manpower deficiencies. The British achieved the same advantages by using eight integrated Gurkha battalions in Malaya. This legacy is not unknown to the US Army, for example, which used Nung, Montagnard, and Meo tribesmen with success in Southeast Asia. However, dangers do exist with this approach if the use of ethnic or religious minorities exacerbates the conflict. This risk can be mitigated by deploying them outside of their native areas or even in other countries – for example, Kurds in Afghanistan or Afghan Baluchis, Tajiks and Uzbeks, or Hazaras in Iraq. Naturally, the recruitment and employment of a specific group can be done only after a careful cultural, religious, and historical analysis of the potential group has been undertaken in order to evaluate its compatibility for use within a specific NATO national army, and in a specific theatre of operations.

Obviously, the motivation of integrated indigenous soldiers has to be scrutinized carefully before embarking upon their use. Incentives are the cornerstone of modern life.29 They can be both tangible and intangible. This adage certainly applies for potential indigenous forces fighting for any country and its national security goals. Besides national, religious, or political reasons, such indigenous forces could be recruited and motivated by a carefully constructed package of inducements that might include a western pension, or the chance for an immigration permit after a certain number of years of satisfactory service. These ideas are not whimsical or speculative. Nepalese Gurkhas receive a pension that enables a comfortable life in their homeland after completion of their duty in the British Army. Similarly, foreigners that complete five years of satisfactory service in the French Foreign Legion receive French citizenship. The ‘turned’ terrorists within the Selous Scouts received pardons for their crimes, medical care, and security for their families, as well as regular army pay. The Eastern volunteers in the German army had the tantalizing reward of national autonomy dangled before them.

CMJ Collection

Russian Cossacks also volunteered for service with the Germans.

Conclusion

Among the NATO allies, the United States, in particular, has tended to expect that the forces of other nations will replace American forces soon after initial operations. If such expectations are not met, American military forces can face substantial and long-term commitments. To sustain a force in a stability operation for any length of time, other forces must be made available.30 As the current operation in Afghanistan illustrates, troop increases are not always forthcoming. Research by both James Quinlivan of the Rand Corporation and John J. McGrath of the Combat Studies Institute on troop densities for contingency operations confirm the principle that certain troop levels, based upon a number of variable factors, are needed to achieve security and pacification for a given area of operations.31 To achieve the necessary troop levels for a particular geography, one option could be to recruit and integrate indigenous soldiers from tribal groups into relevant NATO armies. The British and German historical examples on the use of integrated indigenous formations show a number of benefits accruing in the intelligence collection and manpower augmentation areas. This experience is available for more detailed evaluation.

![]()

Kevin D. Stringer has served as an Active and Reserve Component officer in the US Army. He graduated from both the US Military Academy and the US Army Command and General Staff College, and subsequently earned a PhD in Political Science and International Security from the University of Zurich.

Notes

- “Indigenous” as used here simply connotes troops from the native populations of a region. Where a state or region is multiethnic or multitribal, it embraces all who might serve as trained auxiliaries to the government forces, supporting allies, or occupation forces.

- Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 3-24 / FMFM 3-24, Counterinsurgency (Final Draft) (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, June 2006), pp.1-19.

- For example, two of the more prominent British works were Charles C. E. Callwell’s Small Wars: Their Principles and Practice (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1896) and Sir Charles W. Gwynn’s Imperial Policing (London: Macmillan, 1934).

- Bert H. Cooper, Jr., “Malaya (1948–1960),” in History of Revolutionary Warfare, Vol. 4, Ed. H; M. Hannon, R. S. Ballagh, and J. A. Cope (West Point, NY: US Military Academy Department of History, 1984), pp. 2-23; Sir Robert Thompson, “Emergency in Malaya,” in War in Peace: Conventional and Guerrilla Warfare since 1945; Sir Robert Thompson (ed.) (New York: Harmony Books, 1982), p. 89.

- Cooper, “Malaya,” pp. 2-28; See also H. P. Willmott, “Mau Mau Terror,” in War in Peace, p. 113.

- McGrath, p. 35, p. 40.

- For more on the political and international backdrop, see Richard Mobley, “The Beira Patrol: Britain’s Broken Blockade against Rhodesia,” Naval War College Review 55, No. 1 (Winter 2002), pp. 63-65.

- Lawrence E. Cline, Pseudo Operations and Counterinsurgency: Lessons from Other Countries (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2005), pp. 8-11.

- See <http://www.game-reserve.com/tanzania_ selous_gr.html>.

- Barbara Cole, The Elite: The Story of the Rhodesian Special Air Service (Transkei, South Africa: Three Knights, 1985), pp. 89-90. See Bruce Hoffmann, Jennifer Taw, and David Arnold, Lessons for Contemporary Counterinsurgencies: the Rhodesian Experience (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1991), p. 47. In my opinion, the definitive book on the Selous Scouts is by their founder and commander, Lieutenant Colonel R. F. Reid-Daly, Pamwe Chete: The Legend of the Selous Scouts (Weltevreden Park, South Africa: Covos-Day Books, 1999).

- R. F. Reid-Daly, Selous Scouts, Top Secret War (Galago, Republic of South Africa, 1982), pp. 175-81; See also his Pamwe Chete, p. ii; Robin Moore, Rhodesia (New York: Condor, 1977), p. 127; James K. Bruton, Jr., “Counterinsurgency in Rhodesia,” in Military Review 59 (March 1979), pp. 26-39.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Counterinsurgency (Final Draft) FM 3-24, pp. 1-2.

- See Major Robert Kennedy, German Antiguerrilla Operations in the Balkans (1941-1944), CMH Publication 104-18 (Carlisle, PA: Center for Military History, 1989).

- See, for example, Carlos Caballero Jurado and Kevin Lyles, Foreign Volunteers of the Wehrmacht 1941-45, Men-at-Arms Series 147 (London: Osprey, 1983), p.13; and Eastern Volunteers, <http://axis101.bizland.com/EasternVolunteers1.htm>.

- Carlos Caballero Jurado and Kevin Lyles, Foreign Volunteers of the Wehrmacht 1941-45, p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 15.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 20.

- George Fischer, Soviet Opposition to Stalin: A Case Study in World War II (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952), p. 48.

- Carlos Caballero Jurado and Kevin Lyles, Foreign Volunteers of the Wehrmacht 1941-45, pp. 13, 20.

- George Fischer, Soviet Opposition to Stalin, p. 51.

- Ibid., pp. 48-49.

- See Major Robert Kennedy, German Antiguerrilla Operations in the Balkans (1941-1944).

- See Eastern Volunteers, <http://axis101.bizland.com/ EasternVolunteers1.htm>, accessed August 18, 2006.

- Fischer, pp. 48-49.

- Counterinsurgency (Final Draft), pp. 1-19

- Steven D. Levitt and Stephan J. Dubner. Freakonomics (NY: William Morrow, 2005), p. 13.

- See James T. Quinliven, “Force Requirements in Stability Operations,” Parameters, Winter 1995, pp. 59-69.

- See also James T. Quinliven, “Burden of Victory,” RAND Review, Vol. 27, No. 2, Summer 2003, pp. 28-29, and John J. McGrath. Boots on the Ground: Troop Density in Contingency Operations, Global War on Terrorism Paper No. 16 (Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006) for their views on the necessary troop densities to be successful in counterinsurgency and contingency environments.