This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

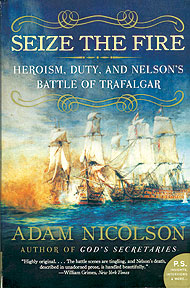

Seize The Fire – Heroism, Duty, And Nelson’s Battle Of Trafalgar

by Adam Nicolson

New York/London/Toronto/Sydney: Harper Perennial, 2005

341 pages, $18.95 (paperback)

Reviewed by Mark Tunnicliffe

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

A historian’s role can be likened to that of a bridge, one of connecting, not one place to another, but, rather, one society to another. The end points of the bridge are two points in time: the distal end is defined by the events, the time, and the society that form the subject of the historian’s dissertation, while the proximal end is the society to which the historian is speaking. Absent any new historical data, revelations, or analysis, the distal end of the historical bridge will not move much, but, as modern society continues to evolve, there is always value in revisiting old events, if for no other reason than to update our understanding of them in light of current ethics, values, and priorities. This demands, of course, that the historian not only understand his subject matter, but his current society as well.

A historian’s role can be likened to that of a bridge, one of connecting, not one place to another, but, rather, one society to another. The end points of the bridge are two points in time: the distal end is defined by the events, the time, and the society that form the subject of the historian’s dissertation, while the proximal end is the society to which the historian is speaking. Absent any new historical data, revelations, or analysis, the distal end of the historical bridge will not move much, but, as modern society continues to evolve, there is always value in revisiting old events, if for no other reason than to update our understanding of them in light of current ethics, values, and priorities. This demands, of course, that the historian not only understand his subject matter, but his current society as well.

The value, then, in a history that revisits an old story covered so often, and, frequently, so very well, lies in the nature of the bridge to today’s society that its author constructs. That Adam Nicolson evidently was conscious of this fact lies in the approach, signaled in the sub-title to his book, that he has taken in his narrative of Britain’s most famous naval battle. For, as he indicates in his preface, a proper “...description of Trafalgar cannot confine itself to the facts of rigging and armament, weather, and weight of broadside...” or, for that matter, the tactics involved, or the strategic implications of the result. Not that Nicolson ignores these elements of the story of Trafalgar, but they are simply peripheral to the main theme of his exposition – the character, the ethos, and (in the author’s language) the “mental landscape” of the men who were engaged. Nicolson’s story of Trafalgar is that of the men who fought there, and the society that shaped them, as interpreted for a 21st Century reader.

The author has divided his dissertation into two sections. The first part, Morning, uses the tactical and strategic approach phases of the engagement as a setting in which to discuss the national character elements of the men who established the conditions for the engagement at Trafalgar. The chapters in this section address the zeal, anxiety, honour, and boldness of the English sailors (largely the officers) that shaped the circumstances of the battle, the tactics they chose, and the supreme self-confidence with which they approached the imminent engagement. The second section, Battle, focuses upon the violence, and, somewhat surprisingly, the nobility and humanity with which the sailors executed the action.

None of these characteristics can be evaluated in isolation, of course. Since the discussion is primarily focused upon Nelson’s fleet, the author’s examination of the French and Spanish crews is limited to the level of detail necessary to establish them as a foil for their adversaries. Nevertheless, his depiction of these awkward allies as being on the one hand feudal (the Spanish), or ill-disciplined and incompetent (the French), is revealing enough. As Nicolson presents the characteristics of the officer corps and the nations that bred them, it seems evident that Trafalgar would be an asymmetric battle with a foregone conclusion (including a 10:1 Allied to English casualty ratio). For Allied officers, the outcome of a naval battle was considered secondary to how it was fought – for the English, victory, whether in battle, commerce, or personal affairs, was everything. The participants knew all of this, and, consequently, despite their inferiority in numbers and tactics that the author characterizes as “immensely weak,” the English fully expected to win, while the French and Spanish patiently awaited defeat.

Similarly, the discourse on the moral characteristics of the victors is largely focused upon their officers, and, not surprisingly, upon Nelson himself. Relatively little is said about the seamen who fought the action – an issue acknowledged by the author. To some extent, this is a natural outcome of the tenor of naval battles. Short of out-and-out mutiny, a crew has little choice but to go where its ship goes – as directed by her officers – and they had little option but to make the best of it. This the British crews did – ignoring the chaos and mutilation around them with continual cheering and devotion to the task at hand. However, part of the lack of reference to the crews reflects the not-surprising paucity of accounts written by the men themselves, and, in the few of their letters available, in the wooden and formulaic way in which they expressed themselves. As the author notes, this would change by the end of the century – the Victorian sailor would become more literate and passionate, and his officers much more reserved.

Nicolson thus concentrates his thesis upon the officer corps of the victorious fleet at Trafalgar, and the mores of the times that shaped and created that corps. This emphasis provides him with a rather unique approach, in that the “revolution” in ethical standards in early 19th Century England affected the totality of the society – its military, politics, commerce, and its arts – in roughly equal measure, and it was expressed equivalently, according to the venue. Consequently, Nicolson chooses to illustrate the military ethos with the (English) artistic one with which it was evolving in parallel. Indeed, the title of the book is a phrase extracted from the second stanza of Blake’s poem, The Tyger, composed a decade before Trafalgar. Both Blake and Nelson, whom Nicolson proposes would have had little empathy with each other, nevertheless understood the millennial atmosphere of the day in their own and complementary ways. But while Blake does not propose the answer to his poetical question, “What the hand dare seize the fire?” Nelson and his brother officers were quite prepared to provide one: they dared. The author uses the works of a number of other contemporary English poets to illustrate further the temper of the times and its people. Wordsworth, Pye, Blake, and Pope are pressed into service to augment extensive quotations from contemporary letters, while illustration (with commentary by the author) provided by English painters like Turner, Beechey, and Head provide alternative interpretations of the events and the character of the main participants through the medium of art.

If one were to have any complaint about the book, it may lie in the detail that the author lavishes upon the various artistic, documentary, and biographical segues which he embarks upon occasionally to ‘beat a point to death.’ For some readers, however, the richness and depth of the book may rest in this very detail. The beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. Nevertheless, this is a highly useful and readable account of the Battle of Trafalgar, and if it does not quite stand completely on its own, it is a valuable addition to the literature on the subject.

Nicolson makes no direct comparison with today’s society – in fact, the only generational comparisons he makes are with the more genteel 18th Century, and the classical Greek, Roman, and Hebrew cultures. It appears that the author is begging the reader to come to his own conclusions as to the relevance of the Trafalgar experience to our own times. Early 19th Century England was imbued with a millennial atmosphere in which almost apocalyptic violence was to be followed by peace and reconciliation. So events appeared to turn out – at least, in the case of England. Immediately after the extreme violence of the battle, English sailors worked alongside their vanquished Spanish and French foes to save ships and lives in the storm that followed – violence followed by humanity. Similarly, the century following the Napoleonic Wars was one of relative peace and great prosperity for England – again, a perceived reward for the sacrifice of all out violence, professionalism, and honour, coupled with humility and humanity.

Does any of this speak to today’s war on terrorism, asymmetric warfare, moral relativity, and amorphous foes? The conclusion is the reader’s to draw, but given the general conduct of the British army in the Falklands, and, more recently in Iraq – one might discern similar characteristics of a very professional application of violence, followed by a similar show of humanity. Perhaps the bridge over the last 200 years is not so long after all.

![]()

Commander (ret’d) Mark Tunnicliffe, who was “promoted to Mister” in October, is currently a Defence Scientist with Defence Research and Development Canada at National Defence Headquarters.