This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Aerospace Initiatives

Photo courtesy of Mike Reyno

NATO AWACS: Alliance Keystone for Out-of-Area Operations

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

“The Alliance is purely defensive in purpose: none of its weapons will ever be used except in self-defence...” (NATO Strategic Concept, November 1991)

Introduction

The evolution of NATO’s raison d’être over the past two decades, from a collective defence organization prepared to defend itself against a single monolithic threat, to its current incarnation as a collective security organization actively engaged in multiple military operations, both within the Euro-Atlantic area and well beyond, is a story of extraordinary institutional transformation. That story has continued to confound skeptics, and to defy all claims that NATO is a Cold War relic well past its prime.

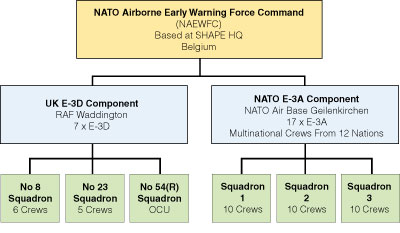

But how consensus could ever be achieved among NATO’s senior decision-makers, to move from the classic Article V response in defence of an attack through the Fulda Gap to a historic agreement on assuming infinitely more complex (non-Article V) responsibilities for the International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, is the real story. In fact, this so-called ‘leap into the unknown’ has occurred gradually, almost imperceptibly at times, and usually in measured phases. More significantly, a closer analysis of precisely how this ‘leap’ occurred reveals that the principal instrument the Alliance used to engineer such a tectonic shift in NATO political/military doctrine has been the NATO Airborne Early Warning Force (NAEWF), with its complement of 17 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft, along with seven British AWACS. It is this tiny NATO-controlled air force that, in fact, has provided the crucial keystone for all subsequent NATO out-of-area operations

Looking back to the tumultuous months after the Berlin Wall fell, to the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, and to the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union, the genesis of NATO’s post Cold War raison d’être appears to be rooted in NATO’s first post Cold War Strategic Concept, announced at the Rome Summit in November 1991. It provided the key for opening the door to Alliance involvement in what subsequently came to be known as out-of-area operations.

Not surprisingly, after decades of institutional inertia, NATO decision-makers were still quite reluctant to step through that door. Moreover, NATO’s sacred principle of consensus decision-making seemed to all but guarantee that any agreement on such operations would be virtually impossible to achieve. Nevertheless, to help ease member nations through this narrow and difficult passage, the NATO Military Authorities (NMA) had, in their strategic quiver, the aforementioned NATO-owned, multi-purpose and multinational force of NATO AWACS. It was not only rapidly deployable, but, as a military unit under NATO’s direct strategic control, it could also be deployed unilaterally by the NMAs (at least initially) without political debate.

And, unlike the Standing Naval Force Atlantic and its soon-to-be-formed sister, the Standing Naval Force Mediterranean, the NATO Airborne Early Warning Force could also be deployed anywhere within the Euro-Atlantic area in a matter of hours. Indeed, where in the past NATO might take days or weeks to consult, to agree upon, and to execute a military response, the Alliance now found itself operating in a new paradigm, whereby NATO forces committed to a crisis could, in fact, respond on the same day, leaving decision-makers little or no time to consider the long-term consequences of such a deployment.

Therefore, in this context, one is led to examine the pivotal role that the NATO Airborne Early Warning Force has played, both as a diplomatic tool and as a keystone in the transformation of NATO from a collective defence organization focused primarily upon self-defence, to a collective security and crisis management organization focused upon out-of-area operations. Arguably, without such a precedent-setting foil it is highly unlikely that NATO ever would have found the subsequent courage to deploy ground forces into the Balkans, to assume command of all coalition forces in Afghanistan, and, ultimately, to evolve into the geo-strategic player that it is today.

Background

NATO and the US AWACS Experience

The establishment of the NAEW Force has much of its roots in the American pioneer experience with modern AEW aircraft. Essentially it was during the Vietnam War, when the US employed EC-121 Lockheed Constellation AEW aircraft in a variety of air battle management and combat support roles, that air commanders began to recognize the great potential of these assets to influence not only the air domain but events upon the land and sea as well. Hence, the US decision in 1965 to produce a modern fleet of AWACS, and to deploy them in sufficient numbers to not only control theatre airspace but through a show of force, to possibly influence political events as well.

Despite much controversy and major reductions in the scope of the program, the first of 34 E-3A Sentry AWACS aircraft was delivered to its operational unit in March 1977.1 And, shortly after reaching initial operational capability, the US began to deploy its AWACS fleet to potential crises around the world. For example, in 1979 AWACS aircraft were sent to Korea as a show of force in the wake of President Park’s assassination. A year later, the US established a forward operating base in Okinawa to monitor ongoing confrontations on the Korean peninsula. Then, later that year, in response to heightening tensions in Poland, and with Soviet forces massing on the Polish frontier, the US supplied NATO with four AWACS to help better monitor the border situation. Subsequently, this well-honed strategy of ‘AWACS diplomacy,’ a much more benign version of gunboat diplomacy from another century, quickly became the standard first-response option in the US political/military decision matrix. It would soon become a similar option for NATO decision-makers as well.

NATO Acquires Its Own Fleet of AWACS Aircraft

In the early1970s, NATO struggled with finding a way to deal effectively with the multiple potential threats posed by high-speed, low-altitude Warsaw Pact bombers – against which its vast network of ground-based radars had serious and limited detection capabilities. The need to confront such a threat was deemed an “urgent requirement” by the NATO Military Authorities.2 But, if AWACS was indeed the solution, it would have to compete for limited financial resources with other military priorities – such as new main battle tanks, fighter aircraft, and modern warships. Military priorities aside though, NATO had an even greater obstacle to overcome when considering an acquisition decision – the requirement to reconcile the national aspirations of 16 sovereign nations, or what Arnold Tessmer referred to as, “...the delightfully maddening confusion and dynamism of parallel decision-making in (16) capitals.”3

Early in Tessmer’s seminal study, Politics of Compromise: NATO and AWACS (1988), we learn that “the acquisition of AWACS” was “...a genuine test of political solidarity,” for never before had NATO nations “agreed to pool resources to acquire a collectively owned and operated defense asset.”4 That said, in late 1978, NATO defence ministers approved the acquisition of 18 AWACS aircraft.5

NATO file photo

Consensus Decision-Making at NATO: A Fundamental Principle

However, upon closer analysis, the nature of this procurement decision appears to be rooted in NATO’s intricate consultative process, and in competing national agendas. More importantly, with respect to the future employment of NATO AWACS, this was a marathon political process that forever marked the NAEWF as an instrument of political will at the strategic level, and not merely an operational tool for military field commanders. Consequently, any appreciation of how NATO AWACS became the political/military keystone for Alliance out-of-area operations must include the exploration of relevant aspects of the decision-making process itself at NATO, which, in fact, is fundamental to any overall understanding of NATO’s post Cold War journey from the Balkans to Afghanistan.

First, the genesis of any military action by NATO usually begins with draft advice prepared by the International Military Staff (IMS) at NATO Headquarters for consideration by the Military Committee (MC). Second, once the MC has achieved consensus on a particular course of action, this advice is forwarded via the NATO International Staff (IS) to the national permanent representatives (PermReps) for their consideration. When the PermReps receive advice from the MC, the process of discussion and consultation is repeated at this “political” level until consensus is achieved yet again. Not surprisingly, however, the final agreed-upon course of action is a political decision that often bears scant resemblance to that document first tabled in the Military Committee.

At first glance, this process, which, by its very nature, commits the Alliance as a whole to a given military action, is arguably imbued with a host of checks and balances, and with what appears to be the necessary ‘off-ramps’ essential to reversing or modifying such decisions. In practice, however, “Alliance” decisions, once agreed upon, are not only binding, but, for all practical purposes, they are virtually irrevocable. This is NATO’s consensus decision-making process, whereby each member nation has been duly consulted, and where hard-won agreements have been reached by “common consent.” Therefore, to reverse or suspend such an agreement likely would undermine the entire consultation and consensus-building process. Moreover, those decisions regarding out-of-area operations are generally reached only after very lengthy consultations, and are, by virtue of their delicate diplomatic nature, rarely reversed, but rather are transformed, reinforced, or enhanced in subsequent collateral decisions.

The net result for NATO is the diplomatic equivalent of: ‘In for a penny, in for a pound.’ In short, once committed, the Alliance never retreats. And, in fact, once NATO AWACS are deployed, subsequent decisions affecting these operations invariably lead to an escalation in NATO’s response to a given crisis, and, often, to a deepening political commitment, which frequently bears little resemblance to the original Alliance agreement on how to respond to that crisis.

NATO Focus Moves Out of Area: AWACS and the First Gulf War

On 2 August 1990, Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait. NATO’s response was modest at first, but, nevertheless, very significant. Within days, in what would come to be known in NATO as Operation Anchor Guard, the Alliance dispatched a number of NATO AWACS aircraft to operate in eastern Turkey, ostensibly to safeguard the southern border of a member nation. Subsequently, as Franco Veltri points out in his history of Allied Forces Southern Europe (AFSOUTH), “the term ‘out-of-area’, for years a taboo if associated with NATO, became a matter of open discussion at (the) political level...”6

In the years since Anchor Guard concluded, NATO has characterized its involvement in this first Gulf War as “indirect.” In fact, Mr. Veltri has written that, “NATO as such was not involved” in the Gulf War. Reality, however, is much different. To be specific, on the second night of the air campaign, US attack aircraft en route to their targets in Iraq began to check in on NATO AWACS control frequencies. In a historic and unprecedented move, the NATO crew (now operating less than 60 miles from the Iraqi border) immediately switched from a routine surveillance and reporting mode to a full combat support role, and assisted with the marshalling of these US forces, passed confirmatory Air Tasking Order information and supported the Coalition forces wherever possible. This included the warning off of one returning attack aircraft that was about to penetrate Syrian airspace.7, 8

The fact that NATO AWACS crews were then directed not to mention any Coalition activities in their standard post sortie mission reports (MISREP)9 helps to explain why NATO’s public position on the war has always been one of non-involvement, how the media believed this to be true, and how it was possible for this myth to become entrenched subsequently in NATO historical accounts. The facts, however, paint an entirely different picture. Clearly, NATO AWACS crews, flying what can only be described as combat support missions,10 operating under the guise of Operation Anchor Guard, and ably assisted by NATO ground environment personnel in Turkey, all became full participants in the air portion of what had now become Operation Desert Storm.11

DND photo FA2006-0294

A multinational NATO AWACS crew working Exercise Maple Flag XXXIX at Cold Lake Alberta, 18 May 2006.

AWACS, the Rome Summit, and NATO’s New Strategic Concept (1991)

Nine months later, NATO Heads of State and Government meeting in Rome, (November 1991), decided “to open a new chapter in the history of (the) Alliance...” and approved a new “Strategic Concept” which underscored the crucial importance of crisis management and noted that, “... Allies could ...be called upon to contribute to global stability and peace by providing forces for United Nations missions.”12

NATO clearly was now prepared to step out on the global security stage, and, in the NAEW Force, it already had a ready capability that could serve such a broad concept of security. Specifically, NATO AWACS offered the requisite strategic flexibility, survivability, versatility, and reliability – in short, a made-to-order multinational force multiplier.13 NATO only needed to have the necessary legitimacy to use such a force, and, in short order, the United Nations would provide just that legitimacy.

NATO, the CSCE (Commission for Security and Cooperation in Europe), and the United Nations

The year 1991 also witnessed the beginning of the break-up of the Republic of Yugoslavia. By September, civil war had broken out, and the United Nations issued the first of what would be 118 separate Security Council Resolutions (UNSCRs) relating to the former Yugoslavia. These led, inter alia, to a “general and complete embargo on all deliveries of weapons and military equipment to Yugoslavia,”14 the establishment of the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR),15 and, on 30 May 1992, to a complete air, land, and sea embargo on any trade, financial transaction, or movement to and from the Republic.

It was in this context of what was now a full-blown Balkan crisis that NATO agreed, in June 1992, “...to support, on a case-by-case basis... peacekeeping activities under the responsibility of the CSCE...” and, perhaps more significantly, reiterated its “... commitment to strengthening that organisation’s ability to carry out its larger endeavours for world peace.”16 Clearly, the leap from regional defensive alliance to being a geo-strategic crisis manager was all but complete. And the key “capacity” required by the Alliance “to assist” the CSCE was already in place – NATO AWACS.

NATO file photo

NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer (centre) onboard an AWACS aircraft, in conversation with two Luftwaffe controllers, 16 March 2006.

NATO AWACS and the Balkans

Over the next eight years, the Alliance would make dozens of critical decisions that would see its role in the Balkans evolve dramatically from observer to crisis manager, and, ultimately, to peace enforcer. And, as NATO political and military involvement expanded in the region, each escalatory step would be preceded by a corresponding increase in AWACS taskings. Major milestones in this process included:

- Operation Maritime Monitor: In July 1992, NATO and the Western European Union (WEU) launched “a coordinated maritime operation in the Adriatic to monitor compliance with UN Resolutions concerning the embargo on Yugoslavia.”17 This “maritime” mission was to be executed by the Standing Naval Force Mediterranean – STANAVFORMED... and other assets as appropriate.”18 Other assets included 24-hour radar coverage of the Adriatic Sea by the NAEW Force, to include newly commissioned British E-3Ds, and French E-3F AWACS.

- Operation Sky Monitor: The September 1992 shoot-down of an Italian Air Force transport attempting to deliver humanitarian aid to Sarajevo prompted the UN to establish a ban on (non NATO/UN) military flights in the air space of Bosnia...”19 NATO’s first response was to establish a No Fly Zone (NFZ) over Bosnia, using AWACS to monitor the situation and to report compliance. Second, in order to optimize AWACS radar coverage over the mountainous terrain of Bosnia, a new surveillance orbit was established over the eastern Adriatic, that, in another historical precedent, took NAEW aircraft outside NATO airspace for the first time. Third, to improve low-level radar coverage further, NATO staff travelled to Budapest, Hungary, to negotiate with this former Warsaw Pact nation the necessary permissions to establish a NATO AWACS orbit over that country.20 The negotiations were highly successful, as were collateral discussions with the Austrian government that were needed to obtain authorization for AWACS aircraft to transit Austrian airspace en route to Hungary. And, on 31 October, the NAEW Force commenced ‘24/7’ operations in Hungarian sovereign airspace – certainly out of area, and far beyond NATO’s geographic borders.

- Operation Maritime Guard/ Sharp Guard: In November 1992, the UN called for actual enforcement of the sea embargo to include halting and searching all ships of interest.21 This resulted in Operation Maritime Guard and, later, Operation Sharp Guard – the first operations of their kind in NATO history. AWACS and its sophisticated maritime radar would play a crucial role in these operations, providing NATO and WEU ships with long-range sea surveillance coverage, without which it would have been impossible for those sea-based assets to execute their mission successfully.

- Operation Deny Flight: Since the establishment of the NFZ over Bosnia, both NATO AWACS and UNPROFOR had reported widespread violations of the ban on military flights. Consequently, on 31 March 1993, the UN banned all fixed and rotary wing flights in Bosnia, and authorized “...all necessary measures” to enforce compliance with this ban.22 Significantly, this was language rarely used by the UN, and never before used in NATO. Two weeks later, NATO began to “enforce” the NFZ over Bosnia, using NATO AWACS and NATO-assigned fighters in what was now known as Operation Deny Flight.

- NATO Support to UN Safe Areas: Within days of the start of Deny Flight, the UN was receiving alarming reports that Bosnian Serb paramilitary units were continuing “deliberate and armed attacks” against innocent civilians.23 In response, the UN established Srebrenica as a safe area, and, three weeks later, created similar safe areas in Sarajevo, Tuzla, Bihac, Gorazde, and Zepa.24 Then, in June 1993, the UN authorized NATO, “...[to use] all necessary measures through the use of airpower...” to assist UNPROFOR with protection of the safe areas.25 For its part, AWACS would again play a critical combat support role in ensuring that the “necessary measures” (i.e. close air support) were effectively executed.

- NATO’s First Air-to-Air Combat: On 28 February 1994, NATO AWACS detected six Bosnian Serb Super Galeb light attack aircraft violating the NFZ, apparently en route to a bombing mission on the Muslim-held town of Novi Travnik. In response, AWACS immediately vectored fighters to the Galebs’ location, and, in accordance with the rules of engagement, broadcast warnings to the violators to “land or exit the No Fly Zone or be engaged.”26 The Serbs did not comply and, within five minutes, four of the six Galebs had been shot down by two pairs of fighters, while the remaining two Galebs were able to exit the NFZ.27 This was, without question, a historic day for NATO. Fighters flying a NATO mission under NATO AWACS control had, for the very first time, used lethal force in prosecuting the NFZ over Bosnia. The news stunned the Alliance, mostly because, in the 45-year history of NATO, it had simply never happened before. And it had all happened out of area...

- NATO’s First Air-to-Ground Combat: The next crucial role tasked to the NAEW Force was to act as airborne mission commander for NATO fighter-bombers conducting air strikes launched in support of UNPROFOR. In the event, NATO first began pinpoint air-to-ground attacks in April 1994, when UNPROFOR military observers in Gorazde had asked for NATO air protection. This Close Air Support (CAS) mission then continued throughout Bosnia for the next year.

- NATO Launches Major Attack on Serbian Airfield: In November 1994, Bosnian Serb aircraft conducted two attacks in the Bihac area of Bosnia. In response, on 21 November, NATO conducted a major air strike on the Udbina airfield in Serb-held Croatia involving 39 combat and combat-support aircraft, all directly under NATO AWACS control. This was the first major air attack of its kind in the history of NATO.28

- NATO Goes to War: The catalyst that generated NATO’s next historic decision was twofold: first, in July 1995 at Srebrenica, the massacre of close to 8000 unarmed Bosnian Muslim men and boys,29 and secondly, on 28 August 1995, a deadly mortar attack at a market in Sarajevo – and both locations were UN-designated safe areas. Although the source of the mortar attack has never been proven, it was assumed to come from the Bosnian Serbs. Clearly, UN demands for the Bosnian Serbs to withdraw at least 20 kilometres from any UN safe area had been completely ignored (i.e., the towns of Zepa and Srebrenica had both been overrun in recent months.) Consequently, NATO and UNPROFOR “...jointly ordered the execution of Operation Deliberate Force.”30 Remarkably, the NATO air campaign lasted only 11 days, not including a four-day suspension after the first 48 hours (30 August – 4 September 1995) to allow the Serbs to comply. They did not, and, thus, the bombing resumed. NATO aircraft, under the direct control of the NAEW Force, flew over 3500 sorties and dropped more than 1000 bombs against nearly 350 separate targets. In short, for two weeks NATO went to war. When it was over, designated safe areas no longer were threatened or under attack.

- Enforcing the Peace in Bosnia: In the aftermath of Deliberate Force, and concomitant Croatian and Bosnian-Croat military offensives, Bosnian Serb para-military forces had been critically weakened. Consequently, on 21 November 1995, in Dayton, Ohio, “...the leaders of Bosnia, Serbia, and Croatia agreed to end a war.”31 On 20 December, Deny Flight operations ceased. NATO’s 970-day peace support air operation was finally over. Looking back, in his 2005 article Crossing the Rubicon, Professor Ryan C. Hendrickson declared that Operation Deliberate Force had “...effectively ended the “out-of-area” debate that had dominated intra-Alliance discussions on NATO’s role since the end of the Cold War.”32 Poised on the “other bank of the Rubicon,” NATO now began an entirely new era as a peacemaker, peace enforcer and peacekeeper, and thus silenced any further criticism that it had “to go ‘out of area’ or it would go ‘out of business.’”33

- NATO IFOR and NATO SFOR: That new era began where the old one had ended – in Bosnia, with a very robust NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR), supported by NATO AWACS, along with a fleet of NATO-assigned fighters in a new mission called Operation Decisive Endeavour – designed to maintain complete NATO air dominance in the Balkans. Within a year, however, and despite the most sanguine expectations, IFOR’s mission was complete, and it was replaced by another new mission – the Stabilization Force (SFOR) – while its air assets were transferred first to Operation Deliberate Guard, and then, 18 months later, to Operation Deliberate Forge. But just as NATO’s withdrawal from the Balkans began to accelerate, its out-of-area odyssey was about to expand, and to do so significantly.

- NATO Goes to War Again: By 1998, open conflict between Serbian military and police forces and Kosovar Albanian forces had resulted in the deaths of more than 1500 Kosovar Albanians, and it had also “...forced 400,000 people from their homes...”34 Hence, the stage was set for another major NATO intervention, this time in Kosovo. In November, OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) cease-fire monitors arrived and were themselves threatened, thus necessitating the establishment of yet another NATO out-of-area mission – the Kosovo Extraction Force. In addition, NATO had commenced an “air verification mission” over Kosovo that was supported by various airborne surveillance platforms including U2s, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and, of course, by NATO AWACS (supported by US AWACS). By March 1999, however, cease-fire monitors no longer could perform their tasks effectively and were therefore withdrawn. And, as they departed, the Serbs commenced a new ground offensive, while final appeals to President Milosevic went unheeded. NATO’s response to President Milosevic’s intransigence was to launch, on 24 March 1999, Operation Allied Force – a textbook demonstration of “coercive airpower.”35 In the event, “...a formidable force of [over 900] NATO aircraft, ...coming from 14 nations and operating from more than 40 different locations, flew in excess of 38,000 sorties...[thousands of which]...were flown into a very robust integrated air defence system [that launched over 600 surface-to-air missiles].”36 AWACS again served as the primary airborne battle manager for all these assets. Despite frequent bad weather, the 78-day air campaign saw the Alliance fly more than 10 times the level of effort seen over Bosnia four years earlier. In the end, Serbia succumbed to overwhelming airpower. More remarkably, the air campaign had achieved its major objective – the full withdrawal of Yugoslav Security Forces from Kosovo, and it had done so without NATO having deployed a single soldier on the ground.

NATO File photo

The Washington Summit and NATO’s New Strategic Concept – 1999

Interestingly, in the middle of the war with Serbia, Alliance leaders met in Washington to celebrate NATO’s 50th anniversary, and to agree to yet another new Strategic Concept, which included some radical changes to NATO’s modus operandi. Foremost of these was NATO’s commitment “...to contribute to effective conflict prevention and to engage actively in crisis management, including crisis response operations.”37 More significantly, however, when considering any geographic limitations to NATO’s reach, the document made it clear that the Alliance would not be bound by such restrictions, declaring that, “...Alliance security must also take account of the global context... including acts of terrorism, sabotage and organized crime, and by the disruption of the flow of vital resources.”38

Clearly, the message to President Milosevic and to others was that NATO’s resolve was stronger than ever before, and that, in the 21st Century, while the Alliance would think regionally, it would act globally. In short, no threat to the Alliance, no matter how distant, would now be able to take refuge in NATO’s traditional paradigms of self-defence and Eurocentric isolationism.

NATO Out of Area Post 1999 – Security in a Global Context

Long after the end of the air campaign over Serbia, NATO continues to operate out of area, in Kosovo, in the Sudan, and, of course, in Afghanistan, where, nearly 3000 kilometres from NATO’s nearest border, it leads the International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF) in NATO’s first and largest ground operation outside Europe. As one NATO expert has so succinctly noted, “...NATO’s operational engagement in Afghanistan [has] truly and irrevocably propelled the Alliance into ‘out-of-area’ operations well beyond its traditional Euro-Atlantic centre of gravity...”39 And so, in the space of only one decade, NATO – once a static, insular, and inward-looking regional defence organization – has transformed itself completely into the geo-political player it is today. But, if one accepts that the NAEW Force has been the principal instrument with which the Alliance has engineered such profound strategic change, and has hence made out-of-area operations the norm, it is worthwhile therefore to briefly consider the future role of NATO AWACS, and where this tool might next take the Alliance.

NATO file photo

NATO AWACS over Niagara Falls during an early visit to Canada.

NATO AWACS – Quo Vadis?

NATO AWACS will continue to directly support NATO in crisis management by providing a full range of political/military options, including, to name just a few, forward presence, show of force, support to maritime and/or air blockade, enforcement of No Fly Zones, counter-terrorism operations, air battle management of joint and combined air operations, including close air support, airborne mission command of combat search and rescue, support to Non-combatant Evacuation Operations (NEO), and support to humanitarian airlifts.

Secondly, work is already underway to develop an updated Strategic Concept for NATO, one that more accurately reflects emerging threats to the Alliance, and NATO’s concomitant focus on global security. And, although the Secretary-General does not see a need for a “global NATO,” he does see a requirement for an Alliance that defends its members against “global threats.”40 In this context, and given the history of NAEW employment over the past 15 years or so, what follows is a list of areas/missions where NATO AWACS could be deployed during the next decade:

- The Ukraine;

- The Persian Gulf;

- The Sudan;

- Iraq;

- The Middle East;

- The Korean Peninsula;

- South Asia;

- The Far East;

- The Southern Mediterranean; and

- For Humanitarian Missions.

Thus, in summation, at a time when the NATO Alliance was desperately struggling with the painful process of redefining its raison d’être, the NATO Airborne Early Warning Force stood ready to implement a new out-of-area doctrine in a practical and benign manner, thereby serving as a catalyst for the Alliance to step up immediately to its new responsibilities on the international stage. And, for those NATO member states hesitant to authorize such missions, subsequent decisions to employ AWACS in a graduated manner slowly conditioned these nations to accept such deployments, to agree to wider deployments out of area, and, ultimately, to authorize robust operations in direct support of the UN.

The genesis of this remarkable institutional transformation has its core roots in the various out-of-area operations conducted by the NATO Airborne Early Warning Force between 1990 and 1999. From NATO’s well-disguised involvement in the first Gulf War, to its support of air and sea embargoes conducted against the Former Republic of Yugoslavia, from control of fighters enforcing the No Fly Zone over Bosnia, to air battle management of air strikes and the Bosnian Air Campaign, from IFOR and SFOR, to an air war with Serbia, AWACS has been a crucial component of NATO political/ military decisions at every step of the way. Moreover, in each instance, the prelude to escalation or to a major shift in NATO’s crisis response efforts was invariably an expansion to NATO AWACS tasking. Such a gradual escalation of NATO AWACS employment throughout the 1990s, both in scope and in intensity, has, in fact, given practical meaning to NATO’s out-of-area concept, making it both a credible and an acceptable NATO doctrine.

NATO file photo

NATO AWACS – Quo Vadis?

Conclusion

NATO AWACS was and is the primary instrument for the Alliance to initiate a tangible response to a given crisis. And, while other NATO assets are vital to such a response, none can match the inherent AWACS capability to respond immediately, or to be “on station” anywhere in the Euro-Atlantic area – and to do so within hours of a tasking. Consequently, with very few exceptions, it can be concluded that, in a given crisis, “no AWACS” very likely means “no out of area” for NATO. But history has also demonstrated that, in the classic “first in, last out” paradigm, once the Alliance commits AWACS, such a tasking very well may endure for years before it is significantly revised or terminated.

Second, since NATO AWACS can fly virtually anywhere in the world, the location of NATO’s next crisis response operation is limited only by one’s imagination. Arguably, this makes any debate about what constitutes “NATO’s backyard” moot at best, but more likely, irrelevant.

Third, notwithstanding the multitude of military tasks that AWACS crews and their sophisticated electronic sensors can undertake, the fundamental conclusion drawn from NATO’s out-of-area activities during the 1990s is that the NATO Airborne Early Warning Force was, and is, primarily, a political instrument, the actions of which represent the pragmatism and collective political will of first 16, then 19, and now 26 sovereign nations. And, because AWACS has always been perceived as a benign, non-threatening weapons system, and has not generally been viewed as a destabilizing force, NATO decision-makers have therefore considered the employment of AWACS from a political perspective, and only secondarily from a military dimension.

Fourth, because NATO AWACS is ostensibly benign and politically safe, it therefore became the de facto keystone for all NATO out-of-area operations in the 1990s, without which many member states, which had opposed this doctrine from the outset, may never have been able to overcome their resistance to this dramatic change in NATO’s approach to collective security.

Fifth, looking ahead to the next decade, crisis management or crisis response operations will not only be one of NATO’s fundamental security tasks, it will likely be the task that preoccupies the Alliance. As a key component of the new NATO Response Force (NRF), NATO AWACS will likely continue its keystone role in out-of-area operations, mainly because it is NATO’s most rapidly deployable capability, and also because the NAEW Force has (with air-to-air refueling) the necessary global reach, upon which future NATO decision-makers will come to depend at the outset of any crisis.

Finally, looking back some 30 years to the fragile beginnings of the NATO AWACS program, any suggestion then that this controversial project might one day blossom into the Alliance’s premier instrument of crisis response would have seemed very remote indeed. That said, it is worth noting that the “politics of compromise,” which initially gave life to NATO AWACS, had the same genetic code that the politics of consensus have today. And so, in the current completely transformed Alliance, and with NATO forces now dispersed across four continents, only time and fortune will really tell whether the paradigm of AWACS diplomacy in the 1990s can be equally and successfully exploited over the longer term in the post 9/11 era. If Arnold Tessmer is still correct, and “...visionaries still man the helm of the North Atlantic Alliance,”41 then it is highly likely that NATO AWACS will continue to play its role effectively as the Alliance keystone for out-of-area operations during the foreseeable future.

![]()

Colonel (ret’d) Patrick M. Dennis, OMM, CD, who holds an MA from the University of Northern Colorado, is a former Aerospace Controller with over 2400 flying hours in NATO and US AWACS. Throughout his career, he accumulated extensive staff and line experience within NATO, and also served as the Canadian Forces Defence Attaché to Israel from 2001 to 2004. He is a graduate of both the United States Joint Forces Staff College, and the NATO Defence College in Rome.

Notes

- Peter Grier, “A Quarter Century of AWACS,” in Air Force Magazine, Vol. 85, No.3, March 2002, p. 3.

- Final Communiqué, DPC in Ministerial Session, 10-11 June 1976, Para. 9.

- Arnold Lee Tessmer, Politics of Compromise: NATO and AWACS (Washington: National Defense University Press, 1988), p. 90.

- Ibid., p. xiii.

- One of NATO’s original 18 aircraft was severely damaged on take-off at Aktion, Greece, 14 July 1996.

- Franco Veltri, “AFSOUTH, 1951-2004: Over Fifty Years Working for Peace and Stability,” 2004, at <http://www.afsouth.nato.int/archives/history.htm>.

- Major Phil Riley (CF), “In the Shadow of the Storm: A Collection of Writings by Canadian Air Weapons Controllers from NAB Geilenkirchen from the Time of Iraq’s Invasion of Kuwait To the End of the Gulf War Aug 90 – Mar 91,” compiled by Captain Bev Ellaschuk (CF), January 1992.

- Ibid., Captain Jim McLean (CF).

- Ibid., Major Marsh Simpson (CF).

- Ibid., Captain Perry Paul (CF).

- Ibid., Major Bill Veenhof (CF).

- “The Alliance’s New Strategic Concept”, 1991, Para 41, at <http://www.nato.int/docu/comm/49-95/c911107a.htm>.

- General John R. Galvin, “From Immediate Defence Towards Long Term Stability,” in NATO Review, Vol. 39, No. 6, Dec. 1991, pp. 14-18.

- UN Security Council, Resolution (SCR) 713, at <http://www.un.org/ Docs/scres/1991/scres91.htm>.

- UN SCR 743, at <http://www.un.org/documents/sc/res/1992/ scres92.htm>.

- Final Communiqué Ministerial Meeting, Oslo, 4 June 1992, Para 11, at <http://www.nato.int/docu/comm/49-95/c920604a.htm>.

- UN SCR 757, dated 30 May 1992.

- Statement on NATO Maritime Operations, Ministerial Session, Helsinki, 10 July 1992, at <http://www.nato.int/docu/comm/49-95/ c920710a.htm>.

- UN SCR 781, dated 9 October 1992.

- The team was led by E-3A Operations Wing Commander Colonel Csaba Hezsely (CF), who, quite fortuitously, was fluent in Hungarian.

- UN SCR 787, dated 16 November 1992.

- UN SCR 816, dated 31 March 1993, at <http://www.un.org/Docs/scres/1993/scres93.htm>.

- UN SCR 819, dated 16 April 1993.

- UN SCR 824, dated 06 May 1993.

- UN SCR 836, dated 04 June 1993.

- Operation Deny Flight, AFSOUTH Fact Sheets, 18 July 2003, at <http://www.afsouth.nato.int/operations/DenyFlight/ DenyFlightFactSheet.htm>.

- Craig Covault, “AWACS, Command Chain Key to NATO Shootdown,” in Aviation Week & Space Technology, Vol. 140, No. 10, 7 March 1994, p. 25.

- Michael O. Beale, Bombs Over Bosnia: The Role of Airpower in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, June 1996).

- Ryan C. Hendrickson, “Crossing the Rubicon”, in NATO Review, Issue 3, August 2005.

- Beale.

- Derek Chollet and Bennett Freeman, “The Secret History of Dayton: U.S. Diplomacy and the Bosnia Peace Process 1995,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 171, 21 November 2005.

- Hendrickson.

- Ibid.

- “NATO’s Role in Relation to the Conflict in Kosovo,” in NATO Historical Overview, 15 July 1999, at <http://www.nato.int/kosovo/history.htm>.

- Dr Joel Hayward, “NATO’s War in the Balkans: A Preliminary Analysis,” in New Zealand Army Journal, No. 21, July 1999, pp. 1-17.

- Veltri.

- “The Alliance’s Strategic Concept,” 23 April 1999, Para 10, at <http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/1999/p99-065e.htm>.

- Ibid., Para 24.

- Diego A. Ruiz Palmer, “The Enduring Influence of Operations on NATO’s Transformation,” in NATO Review, Winter 2006.

- Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, NATO Secretary General, “Global NATO: Overdue or Overstretch?” in Security & Defence Agenda, 6 November 2006, Brussels.

- Tessmer, p. 157.