This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Military History

CMJ collection

A French Rubis Class SSN, a type that had been given serious consideration by the Canadian Navy.

Sovereignty, Security and the Canadian Nuclear Submarine Program

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

On 5 June 1987, the Brian Mulroney Progressive Conservative government of Canada unveiled to the House of Commons its White Paper on national defence. The document, Challenge and Commitment: A Defence Policy for Canada, was advertised as a plan to rejuvenate the Canadian military, which the Conservatives had long accused former Liberal governments of ignoring and allowing to decline. The White Paper was a comprehensive document, seeking new equipment for all three services for use in both Europe and Canada in an attempt to enhance Canada’s contribution to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), national defence, and Canadian sovereignty. The ‘crown jewel’ of the White Paper, however, was the concept of a three-ocean navy and the planned acquisition of 10 to 12 nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs). This submarine purchase, intended to be the largest acquisition program in the history of the Canadian military, represented a fundamental shift from the Canadian Atlantist alliance-oriented policy toward a program more inclined toward the protection of Canadian territory, and, particularly, the maintenance of national sovereignty.1

The Strategic Background and the Perceived Imperative

The late 1980s were a time of great concern with respect to Canadian Arctic sovereignty. Of most importance to the Canadian government was the status of the North West Passage. The American refusal to acknowledge Canadian control over these waters, along with widespread rumours that both American and Soviet nuclear submarines regularly patrolled the region, had provoked a general fear that a lack of Canadian surveillance, control, and physical presence in its northern waters, might seriously imperil its claims to ownership. The 1987 White Paper was, in large part, a response to that fear. The acquisition of nuclear submarines would provide an attractive remedy to the Canadian defence dilemma, as the SSN was a platform capable of meeting all the government’s sovereignty and defence requirements. In addition to providing the Canadian Navy with a more respectable presence in both the Atlantic and Pacific, the SSN was the only tool capable of extending the navy’s reach into Canada’s ice-covered Arctic waters. Most importantly, by extending its influence north, the Canadian government hoped to demonstrate sovereignty by exerting a previously impossible degree of physical control over the North West Passage. The defence and sovereignty roles that these submarines were expected to play were thus not two separate tasks but part of one consistent mission, that of asserting sovereignty over Arctic waters by demonstrating a measure of real control.

The 1987 White Paper on Defence was a plan to plug the ‘commitment capability gap’ that had arisen between Canada’s commitments to collective defence and national security, and the Canadian Forces’ ability to meet these responsibilities. While the scope of the program was broad, the centrepiece of the document was undoubtedly the focus upon the navy, the Arctic, and the concept of a three-ocean fleet. This focus becomes obvious from even a cursory glance at the White Paper. On the cover of the document is an unusual global Arctic projection map with emphasis placed on the Arctic Ocean and the Canadian North. Throughout the document, every map of Canada (in relation to the rest of the world) continues to make this emphasis. Canada is presented visually by the White Paper as a northern country with obvious sovereignty and security responsibilities in the Arctic.

The SSN was seen as the ideal weapon for the Canadian Navy in 1987, due to its unparalleled mobility and versatility. These boats were capable of travelling under the Arctic icecap, giving them the ability to travel from the Atlantic to the Pacific, through the North West Passage, in just 14 days.2 During wartime, this ability would allow rapid reinforcement between the oceans and would provide Canada with the capability to destroy intruding Soviet submarines within its Artic waters. In peacetime, the SSN would allow Canada to patrol its Arctic, to detect intruders, and to establish a powerful presence in a region where Canadian sovereignty was not recognized by a number of important nations, including the United States.

CMJ collection

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney

Canadian Arctic sovereignty issues had caused anxiety in Ottawa since the region was first transferred to Canadian jurisdiction in 1880. However, by the 1980s, this concern had shifted from control over the land, to control over the water (or ice) surrounding the landmass. The time during which the 1987 White Paper was written had witnessed a dramatic increase in Canadian concern over the North West Passage in terms of both sovereignty and security. The passage, an inter-oceanic waterway running from the Atlantic through the Arctic Archipelago to the Pacific, had been officially claimed as internal Canadian waters by the Mulroney government in 1986 through the charting and application of straight baselines.3 However, without the recognition of foreign governments or a physical presence in the region to support these claims, Canada’s legal position was tenuous at best.

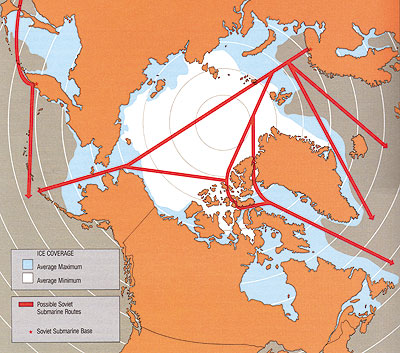

To exacerbate matters, recent developments in military technology were beginning to give Arctic waters a more important strategic significance. The greatest fear from the region came from cruise-missile-firing Soviet submarines. From firing positions in the Lawrence Sea or the Davis Strait, Soviet missiles with a range of up to 5000 kilometres had the ability to reach an alarming number of North American cities.4 By 1987, the USSR possessed 80 SSNs and 62 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) capable of firing cruise missiles. It was feared that these submarines, the majority of which were already stationed on the Kola Peninsula in the Russian Arctic, firing cruise missiles far more difficult to detect than the traditional intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), could provide the Soviets with a devastating first-strike capability.5 In addition to providing firing positions, it was feared that the Canadian Arctic could also serve as a convenient route by which Soviet submarines could bypass the Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom (GIUK) gap to the east, where NATO had always prepared to meet any Soviet submarine breakout into the Atlantic convoy lanes.6

Challenge and Commitment – A Defence Policy for Canada

At the time of the 1987 White Paper, there was a concern that Soviet nuclear submarines could reach both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by transiting under the Arctic icecap.

In addition to its increasing strategic importance, Canadian Arctic waters were also increasing in economic value.7 Recent gas and oil discoveries, and the growing profitability of a number of mines in the Arctic Archipelago gave many the impression that the north might soon realize its potential as a source of great wealth.8 The American tanker Manhattan had demonstrated the possibility of using the North West Passage as a route by which the eastern US seaboard could be supplied with Alaskan oil, while the 1985 voyage of the US coastguard icebreaker Polar Sea had made it abundantly clear that the United States did not recognize Canadian claims to this potentially vital sea route.

United States Navy (USN) activities were not limited to single icebreaker transits, and they were increasing throughout the 1980s. In 1985 USN Vice-Admiral DeMers told Congress that at least “...one or more United States submarines every year” was travelling to the North Pole.9 In 1987, the USN published photos for the first time of American submarines at the North Pole and announced the construction of at least 17 new submarines designed specifically for under-ice operations.10 Meanwhile, Canadian sovereignty over these increasingly important waters rested upon little more than proclamations made by politicians in Ottawa. Its de jure control was disputed by its superpower neighbour and its de facto control was confined to rare overflights by patrol aircraft (from 16 flights in 1985 to 20 in 1986), the utility of which were limited.11 Without an underwater presence to monitor American activity and defend against potential Soviet attacks, Canada could not claim the exercise of supreme authority within the confines of its territory, a central requirement to any definition of sovereignty. In the words of political scientist John McGee: “The meaning for Canadians [was] simple. Either we take on a reasonable share of patrolling the Arctic or we shall be deemed, in terms of realpolitik, to have ceded sovereignty to the Americans.”12 The primary purpose of the proposed SSNs was to remedy this situation; to bring a Canadian military presence into the region to monitor, defend, and control Canadian waters in the hope of preserving Canadian sovereignty.

CMJ collection

The vastness of Canada’s north becomes obvious through this Central Europe overlay of the territory.

The new focus upon Arctic defence and sovereignty represented a fundamental shift from the primarily alliance-oriented naval strategy under which the Canadian Navy had always operated. Previously, Canada had been little concerned with submarines. In 1987, the navy had only three Oberon Class boats that were rapidly approaching obsolescence, and the role of Canada’s navy throughout its history had been one of escort, resupply, and anti-submarine warfare. To this end, during the latter half of the 20th Century, Canada had focused its efforts largely upon a surface fleet of frigates and destroyers that were ideally suited to these tasks. The acquisition of a large fleet of SSNs was thus totally out of character for the Canadian Navy. This radical shift in hardware can only be explained by a radical shift in objectives. It was unlikely that the SSNs were intended primarily for antisubmarine warfare in the Atlantic and Pacific since an adherence to Canada’s traditional surface fleet program could have accomplished this more efficiently for less money and less political turmoil. The SSNs must have been intended primarily for use in the only region that demanded this radical shift in mentality and hardware, the Arctic.

CMJ collection

HMCS Ojibwa, the first of three Oberon Class submarines in Canadian naval service.

Sovereignty Implications

The notion of sovereignty is a nebulous one. However, at its core is the concept of control over a given space. Sovereignty, as defined by the Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs is: “...[the] prevention of trespass, the provision of services and the enforcement of national and international law within (Canadian) territory, waters and airspace.”13 To be sovereign, a nation must thus to be able to “...administer and control its territories and, when necessary, defend its territorial integrity through the effective application of force.”14 Canada’s objective in acquiring an ability to operate under the Artic icecap was to claim this ability; to intercept any Soviet submarines operating within Canadian territory, and to monitor the boats its allies deployed within its territorial waters. Without this capability, Ottawa could not contend to control its northern waters, and its possession of sovereignty, in both a legal and practical sense, would be limited. Even the simple possession of SSNs, regardless of whether they were deployed to the Arctic on a continual basis, would provide a degree of deterrence against trespass, since, unlike an icebreaker, they provided, not a visible presence but a perceived presence. Vice-Admiral James Woods put it succinctly when he said: “...the nice thing about nuclear subs is that you can do what the British did in the Falklands... say they are there.”15

During the course of the debate over the acquisition of the SSNs, a number of alternatives were proposed that were intended to offer Canada the ability to monitor or guard its Arctic waters without the excessive cost of nuclear submarines. The idea of an underwater sonar network was presented as such an alternative, as was the concept of defending the north by mining the Arctic passageway in wartime.16 However, the idea of a Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) – style sonar system was dismissed as offering monitoring without enforcement, felt equitable to buying an alarm system but not hiring a policeman. The idea of mines was rejected – not only because they would prove both expensive and unworkable but also because they, like the underwater sonar system, would not provide Canada with what it needed most, a physical presence exercising authority over its territorial waters.17 Without that physical presence, there would be no deterrent to trespassers, Canadian sovereignty would be disregarded, and the Soviet Union would, in the words of Conservative MP Marc Ferland, “...keep laughing at us as they are doing right now.”18

In addition to guarding the region against its enemies, the SSN program was designed to safeguard it against Canada’s friends. While the greatest threat to Canadian security came from the USSR, the “...greatest threat to Canadian sovereignty in [the] Arctic [was] the U.S.”19 A concern raised by the Special Joint Committee on Canada’s International Relations was that, in the event that Canada wanted to take action against an intruder in its Arctic waters, it would have to call upon American submarines for assistance. With under-ice-capable boats of its own, Canada would strengthen its claims to sovereignty by allowing the Canadian Navy to act independently of the US Navy. Equally important, the mere presence of Canadian submarines in the north would force the United States to share information regarding its submarine movements in the area.20 According to NATO’s underwater management scheme, a Canadian submarine presence in the Arctic region would require the USN to notify Canada of any and all submarine movements in order to avoid a possible misidentification.21 Thus, the mere ability to send submarines to the Arctic would, with regard to the Americans and British at least, have offered Canada a far better understanding of what was transpiring in their North.

CMJ Collection

Perrin Beatty as Minister of National Defence.

Minister of National Defence Perrin Beatty knew that Canada’s case for sovereignty directly contravened the American position of the North West Passage as an international strait, and, when writing the White Paper, he had the American threat in mind. In the summer of 1987, he wrote:

In addition to deterrence and defence, the new thrust of exploration of the seabed and competition for resources that may be found in the Arctic could lead to disputes about sovereignty over maritime supremacy and rights of passage. While these are unlikely to be settled by gunboat diplomacy, Canada would be in a much stronger position to press her claims if she possessed adequate capabilities to establish surveillance and presence in the contested waters.22

In 1931, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) had ruled that it was the exercise of authority within a territory that was the principal consideration when dealing with matters of sovereignty. This control even superceded prior claims to discovery or contiguity.23 In 1985, during the passage of the Polar Sea through contested waters, an international tribunal would have undoubtedly found Canada’s claim to Arctic waters as historic internal waters “...indifferently pursued and inconsistently expressed,” which would have seriously damaged the Canadian legal position.24 During another boundary dispute in the Gulf of Maine, which went before the ICJ from 1981 to 1984, the Canadian lawyers emphasized events in recent (the previous decade) history, while the United States focused upon historical occupation. In the event of a similar case over the North West Passage, an idea officially endorsed by the Canadian government in 1985, the presence of even a few Canadian submarines in the region would have gone a long way toward establishing a precedent of Canadian control and occupation.25 Thus while ‘gunboat diplomacy’ may not have been a solution in the strictest sense, it was intended to provide Canada with a vital legal precedent when and if Canada was ever forced to prove its occupation of its northern waters,

The SSN purchase was not meant to accomplish this goal of asserting Canadian control independently; it was merely the keystone in a larger attempt to bring a Canadian presence to the Arctic. In addition to the nuclear submarines, Beatty had asked for an underwater sonar detection system, five forward operations sites for air defence fighters (at Rankin, Inuvik, Yellowknife, Iqualit, and Kuajjuaq), a new headquarters and more equipment for the Canadian Rangers, a new High Arctic training centre at Nanisivik, new reconnaissance aircraft, a northern-terrain vehicle fleet, and a Polar Class 8 icebreaker.26 Thus, the defence of Arctic sovereignty was a serious concern that the Conservative government had pledged itself to addressing by bringing a Canadian military presence into the Arctic to ensure Canadian security while safeguarding Canadian sovereignty.

The ideas of sovereignty and security were brought together in the White Paper in a unique way. In the 1971 Defence White Paper, the Trudeau government had focused sovereignty concerns upon non-military threats, such as pollution.27 Unlike the approach taken by the Liberals in the 1970s, the Conservative government of Mulroney saw sovereignty and security as being intimately connected. For Beatty and the Conservatives, enhancing security in the North would bring about a corresponding increase in national sovereignty. The program laid out in the White Paper was meant not only to ensure that Canada was secure from Soviet missile firing submarines but also to make sure that it was Canada and not the United States that was doing the securing. If the Canadian government had been strictly concerned with security, the most efficient path to follow would have been to allow the USN to continue to operate in the Arctic while devoting Canadian resources to areas where, historically, they have been applied more effectively.

wikimedia.org

The Northwest Passage and its approach corridors.

However, in 1987, the Canadian government’s chief concern was not Soviet attack; it was of being considered an international ‘freeloader.’ In 1986, only a year before the White Paper, the Department of National Defence (DND) admitted that there was no reason to believe that Soviet submarines regularly trespassed in Canadian Arctic waters.28 Because of the confined nature of the North West Passage, the difficulty inherent in surfacing and communicating through ice, and the relative ease of guarding the exit choke points (Lancaster and Smith Sounds and Davis Strait), it was considered unlikely that the USSR would send its boats through Canadian territory unless it became absolutely necessary. As for cruise missile launches, there were, in fact, relatively few good launch sites that could not be easily guarded. More to the point, the USSR could have devastated North America and Western Europe easily with Sea Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs) without Soviet SSBNs ever having to leave their home waters in the Barents Sea. In a strictly military sense, SSNs and cruise missiles were neither NATO’s nor Canada’s highest security priority.29

While the threat of a Soviet attack from the Arctic was very real, in 1987, this threat was insufficient to warrant the funds that the Canadian government planned to spend upon northern defence, since what danger did exist was already being countered largely by American SSNs.30 In fact, if war did break out, American maritime strategy called for a full submarine offensive into the Barents Sea, meaning that unless the Canadian Navy was willing to participate in this forward maritime strategy, which was seen as destabilizing and highly unpopular in Canada, Canadian SSNs would have little to do.

Photo by Jan Curtis, from www.geo.mtu.edu

Despite the White Paper’s assertion that a Canadian submarine force would be a valuable addition to NATO, and despite the DND contention that Canada’s allies welcomed the acquisition,31 some sections of the American navy and government were “appalled” at what they saw as Canadian military interference aimed only at resolving a Canadian-American sovereignty dispute.32 During a 1987 trip to Washington to secure the transfer of American nuclear technology from Britain to Canada, as was required by the 1958 US Arms Control Export Act, Perrin Beatty and his associates were told in no uncertain terms by the U.S. Defence Department and submarine service officials that a Canadian nuclear submarine program was unnecessary and even unwelcome.33

The Canadian SSNs were not meant primarily as a contribution to NATO, nor were they a response to purely security concerns. Rather, the program was designed to allay the fear of Canada becoming a “dependent.”34 The Defence Update 1988-89 states: “...[that] to be a truly independent nation we must shoulder the responsibilities that come with independence by contributing more fully to our own defence. If we are to be truly sovereign, we cannot ‘contract out’ the defence of Canada.”35 It was this notion, that “Canada [must] play a responsible role in the defence of Canada” that is frequently emphasized in DND publications and statements until the 1990s and the ‘death’ of the 1987 White Paper.36 Perrin Beatty recognized that Canada did not need nuclear submarines purely for security, which was already provided by the Americans. However, to delegate the responsibility for Canada’s security to the USN would have placed Canada in a position of complete dependence unbefitting a sovereign state.

What Might Have Been

The acquisition of the SSNs would have done more than support Canadian claims to the Arctic. It would have allowed Canada to claim that it was contributing its fair share in NATO. It would have provided Canada with a degree of credibility that two decades of neglect had eroded. In Perrin Beatty’s words: “We can be judged sovereign to the degree to which, in the context of alliance and collective defence, we can contribute to our own national security.”37 Canadian SSNs, coupled with Canadian Navy frigates and destroyers (either built or under construction), would have given Canada a balanced fleet.38 In 1987, Canadian admirals were already talking in terms of future independent Canadian task forces that would have given Canada something to ‘bring to the table’ when dealing with its NATO allies.39 This move to “hoist Canada into the world of naval big league” was an attempt to pull back from the abyss of irrelevancy in NATO, and to prove that Canada was an independent nation with the ability to control its own waters, its own territory, and participate on an equal footing with its allies.40

CMJ collection

A British Trafalgar Class submarine, a follow-on to the Swiftsure Class of SSNs that was also being considered for Canadian acquisition.

The Canadian nuclear submarine program, and most of the programs outlined in the White Paper were, however, never undertaken. By January 1989, Perrin Beatty had left DND and had been replaced as Minister by Bill McKnight. And, by May 1988, when the cabinet failed to meet to discuss the SSN contract, the plan was essentially if not officially dead.41 This cancellation was due to a combination of factors, including a serious budget squeeze and the rapid decline and collapse of the Soviet Union.42

The Cold War was dying, as was public desire to spend upwards of $C10 billion on a defence project. The public rationale for the White Paper program was based upon the notion that the Soviet Union was an implacable “...ideological, political, and economic adversary whose explicit long-term aim [was] to mould the world in its own image.”43 The imagery and language of the White Paper was designed to convey the impression of imminent peril, and, once that threat began to melt away, so did public support for Cold War projects. The decline in public support for the SSN acquisition paralleled the decline in East-West tensions. In June 1987, 50 percent of Canadians backed the purchase (with 37 percent opposed).44 A little more than a year later, opposition had increased to 60 percent.45 By 1989, 71 percent were against the purchase, as most Canadians polled expressed a belief that a Soviet attack was highly unlikely.46

Domestically, the Conservative government had a substantial deficit to battle, and, in the end, the most powerful opponents were not from outside the government, but from within it. Rebuilding the military was considered simply unaffordable. Following the 1988 election, the government’s priorities changed, and fighting the deficit became the decisive issue.47 After their re-election in 1988, the Tories slashed 38 percent out of the defence budget and allowed defence spending to fall each year as a budget percentage.48

It was this rush to collect a ‘peace dividend’ that ultimately killed the submarine acquisition plan and most of the White Paper. Only two years after the White Paper was first presented, Defence Minister McKnight stated that the task of defending Canada’s under-ice sovereignty would be left to the United States and Britain respectively, explaining: “...[that] there [were] better ways of defending northern sovereignty but unfortunately we cannot afford those ways.”49 As such, the Canadian government effectively contracted out the defence of its Arctic sovereignty to a neigh-bouring power that did not recognize its claim to it. For Canada, the price of Arctic sovereignty had, once again, proven too high.

DND photo HS2007-G025-006

A Canadian Victoria Class submarine (HMCS Corner Brook) during a summer 2007 deployment to Canadian Arctic waters.

Conclusion

The idea of a Canadian SSN fleet died on a balance sheet, and with it, the White Paper’s attempt to extend Canadian control over the North West Passage. And it was that control that the Canadian government had sought when it decided to alter radically its maritime strategy and to pursue nuclear submarines. A departure from the previous Liberal understanding of defence, the 1987 White Paper functioned under the assumption that a state’s sovereignty was directly related to its ability to defend itself from foreign attack in wartime while controlling its national territory and providing for its own safety in peacetime. It was with this logic that Perrin Beatty decided that a Canadian SSN fleet would be the ideal solution for asserting Canada’s sovereignty. It was considered necessary that, for the purposes of Canadian sovereignty and self-respect, it be Canadian forces providing for the defence of Canadian waters. To allow the USN to continue to provide Arctic security invariably would weaken Canada’s claims to its northern waters and would be incompatible with the responsibilities of Canada as an independent nation. The issue was not simply a matter of security but whether Canada would have the tools to provide that security. For, according to Perrin Beatty, a nation that contracts out the defence of its own territory is not sovereign, but a protectorate.50

![]()

Adam Lajeunesse holds a Masters degree in history from the University of Calgary. His theses examined Canadian-American relations in the Canadian Arctic throughout the Cold War period, and he will be commencing a PhD program this autumn.

Notes

- The Canadian Submarine Acquisition Project: A Report on the Standing Committee on National Defence, Second Report, Issue 41 (Tuesday, 16 August 1988), p. 1.

- A similar transit would take 28 days through the Panama Canal and two months around Tierra del Fuego; House of Commons, Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence of the Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs [hereafter referred to as Proceedings], evidence presented by Rear-Admiral Anderson, Section 24:29.

- A step building upon the actions of the Trudeau government in 1970, which established a 100 nautical mile Pollution Prevention Zone and a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone.

- F.W. Crickard, “Nuclear-Fueled Submarines: The Strategic Rationale,” in Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Winter 1987), p. 19.

- Proceedings, evidence presented by Rear-Admiral Anderson, Section 24:28.

- Canada: Department of National Defence, Challenge and Commitment: A Defence Policy for Canada (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1987), p. 11.

- Indeed, Canadian participation in the defence of its seabed was considered by some to be more important than the defence of its airspace, since the seabed contained infinitely more riches to be defended; John Honderich, Arctic Imperative: Is Canada losing its North? (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), pp. 55-6.

- Tony German, The Sea is at Our Gates: The History of the Canadian Navy (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), p. 318.

- John Harbran, “Yankee Sub, Go Home,” US Naval Proceedings, Vol. 114, (August, 1988), p. 88.

- Ibid.

- Exercise Norploy ‘86 saw the dispatch of two Canadian Navy vessels to Davis Strait, Baffin Bay, Lancaster Sound, and Barrow Strait to show the flag. However, their presence lasted only two months and they could not penetrate farther than the ice line.

- John E. McGee, “Call to the Arctic,” in US Naval Proceedings, Vol. 114, (March, 1988), p. 90.

- The Canadian Submarine Acquisition Project: A Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence, Second Report (Tuesday, 2 February 1988), Section 17:14.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Harbran, p. 88.

- The White Paper did plan an underwater listening system. However, it was designed to operate in tandem with the SSNs rather than independent of them.

- Proceedings, evidence provided by Mr. Blackburn, Section 25:33.

- Proceedings, evidence provided by Mr. Ferland, Section 25:26.

- Joe Clark quoted in: The Globe and Mail, 29 April 1987, p. A5.

- The Wednesday Report: Canada’s Aerospace and Defence Weekly, at <http://twr.mobrien.com/articles/historical/historical-2004-3.htm>.

- Rob Huebert, “Canadian Arctic Maritime Sovereignty – The Return to Canada’s Third Ocean,” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer 2007), p. 14.

- Perrin Beatty, “A Defence Policy for Canada,” in Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 1, (Summer 1987), p. 8.

- Shelagh Grant, Sovereignty or Security? (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1988), p. 315, Note 31.

- Library of Parliament: Political and Social Affairs Division, Canadian Defence Policy Backgrounder (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1988), p. 20.

- Ibid.

- It was also at this time the DEW line was being taken over by Canadian forces and refurbished to create the Northern Warning System; Canada, Department of National Defence, Defence Update 1988-89 (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1988), pp. 10-13.

- Canada: Department of National Defence, Defence in the 70’s (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1971) pp. 1-8.

- Proceedings, evidence presented by Vice-Admiral Brodeur, Section 1:37.

- Matwin S Davis, “Le Mieux est L’Ennemi du Bien,” in Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Fall 1988), p. 54.

- R.B. Byers, “An Independent Maritime Strategy for Canada,” in Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Summer 1988), p. 28.

- Britain and France welcomed the decision because it was from one of them that Canada would buy its submarines; Proceedings, evidence presented by Mr. Manson, Section 24:44.

- Julie H. Ferguson, Through a Canadian Periscope (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1995), pp. 313-14. Byers, p., 28.

- Ferguson, p. 315.

- Perrin Beatty: Canada, House of Commons, Debates, (5 June 1987), p. 6777.

- Canada: Department of National Defence, Defence Update 1988-89 (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1988), p. 1.

- Canada: Department of National Defence, Defence ‘86 –’90 (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1987).

- Bruce Johnson, “Three-Ocean Strategy: Right for Canada, Right for NATO,” in Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Winter 1988), p. 38.

- Challenge and Commitment, p. 52

- Proceedings, evidence presented by Minister of National Defence Beatty, Section 25:26.

- Toronto Star, 6 June 1987, p. 1.

- The plan was officially terminated in April 1989.

- The program’s proponents promoted it on the understanding that the Soviet threat would remain the same, and even increase over the next 20 years. Proceedings, evidence presented by Rear-Admiral Anderson, Section 24:8.

- Challenge and Commitment, p. 5.

- Ottawa Citizen, “50% Back Subs,” 22 June 1987, p. A4.

- John Manthorpe, “Poll says no to Nuclear-Powered Subs,” in Ottawa Citizen, 26 May 1988, p. A4.

- Toronto Star, “Torpedo the Subs for Budget Fairness,” 25 April 1989, p. A18. Doug Ward, “Canadians Disbelieve Soviet Threat Poll Finds,” in Vancouver Sun, 22 April 1988, p. A8.

- Perrin Beatty, 30 March 2006, Re: Nuclear Submarines. [e-mail to Dr. David Bercuson.]

- Defence Update ‘86 – ‘90.

- Vancouver Sun, “Canada to Turn to U.S. after Subs Sunk,” 28 April 1989, p. A9.

- Perrin Beatty, The Globe and Mail, 20 July 1987, p. A8.