This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Lessons From The Past

National Portrait Gallery

London NPG P324

A very colourful warrior and military strategist: Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence, by B.E. Leeson.

Political Warfare Is A Double-edged Sword: The Rise And Fall Of The French Counter-insurgency In Algeria

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Although renowned thinkers and strategists, from Sun Tzu to Mao, to Miere de Corvey, T. E. Lawrence, and Vo Nguyen Giap, have theorized about subversive warfare, La Petite Guerre, as Clausewitz and Jomini referred to it, continued to be marginal and limited to a support function until the 20th Century. At that time, it regained prominence, especially among national liberation movements, in the form of psychological warfare and revolutionary guerrilla tactics.

At their expense, the world’s great powers are discovering one-by-one how limited is their military supremacy in the face of this particular form of warfare, which has neither a front nor a battlefield, and whose purpose is to conquer minds, rather than territories. Having been defeated by the Viet Minh, an elusive enemy that employed the concept of Revolutionary Warfare, the French staff headquarters applied the lessons learned in Indochina and decided to mount a counterinsurgency against the Algerian rebellion of 1954. Although this new warfare doctrine helped cut the National Liberation Front (FLN) from its popular base, it proved to be a double-edged sword, in that it led to the politicization of the French army, which would gradually abandon its traditional role.

This article will examine how French counter-revolutionary warfare in Algeria developed, how it was implemented, and what successes it achieved. It will also focus upon how the strategy impacted the traditional practices and structures of the army, with a view to better understanding the reasons that caused the French government to begin dismantling the army in 1959. The objective here is to elaborate upon the notion of a doctrine that became a vérité devenue folle1 [truth run amok], which resulted in the Grande Muette (the army) overextending its responsibilities, establishing for itself a political conscience, and rising against a central national power suspected of trying to betray its initial mission. The purpose of examining this ideologization and its possible role in the failure of the counterinsurgency experiment is also to better grasp the principles and the perverse impacts of a strategy that would play an increasingly important role in conflicts and in international relations during the 21th Century.

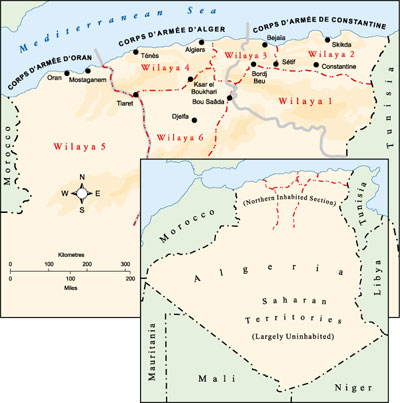

Map by Christopher Johnson

The disposition of the three French corps and the boundaries of the FLN political-military commands during the Algerian War.

Genesis (August 1954-December 1955)

The Hypothesis

Revolutionary warfare is different from traditional warfare, in that, beyond the battle against an enemy’s armed forces, the war effort targets the entire population, whose conquest constitutes a higher aim than taking possession of a territory or dominating a battlefield.2 As in traditional warfare, it is important to know the landscape in order to adapt a strategy to it, although the terrain is of a different kind: “...Revolutionary warfare exploits the political and psychological dimensions of people within a social geography. That is why any use of revolutionary warfare must be subjected to a rigorous political analysis to determine the psychological trends and the meaning of the evolution taking place.”3 Consequently, an army engaged in revolutionary warfare must establish guidelines, a policy framework which will guide its conduct of the battle: “In short, subversive warfare requires that combatants not only be weapon technicians but also, perhaps even more, heads of supporters, crowd leaders, political agitators, unionists, [and] missionaries.”4

In Indochina, the French army found out at its expense the virtues of an art in which its Viet Minh adversary was master. General Giap, the victor at Dien-Bien-Phù, had apparently declared, “The French army was beaten because it did not do enough politicking.”5 Once it had infected the French army, the revolutionary warfare virus would gradually contaminate the intellectual strata of the armed forces. General Lionel Max Chassin was the first to catch it: “The time has come for the army to stop being la Grande Muette; the time has come for the free world to resort to some of its adversary’s methods, if it does not to die a violent death. But one of those methods, and undoubtedly the most important, resides in the ideological role which, behind the Iron Curtain, is relegated to military forces.”6 However, it would be several months before Chassin’s wishes would become reality.

Development and Implementation

After a relatively short incubation period, the Asian Fever spread to the heart of the Algerian guerrillas, the new operational theatre where the French army was fighting the rebellion that began on All-Saints Day in 1954. Thus, the army faced the same challenge it did in Indochina; its numerical superiority was of no use against an enemy who refused close engagement. With the situation worsening, senior political and military leaders recognized that the time had come to employ a psychological weapon.

Between the autumn of 1954 and late-1955, the French army gradually adapted, then structured, revolutionary warfare. During that first phase, the doctrine went from being an experimental weapon, to the official status of being the Seventh Weapon. In March 1955, an agency for psychological action was established and given the name Bureau régional d’action psychologique [Regional Office for Psychological Action], which later became simply known as the Bureau psychologique.7 In July 1955, an Order from the commanding officer in Algeria formalized the psychological action organization throughout the 10th Algerian Military Region. The October 1955 Order respecting the psychological warfare officially defined psychological warfare as, “ [the] systematic implementation of various measures and means designed to influence the opinion, feelings, attitude and behaviour of declared enemies (military and civilian population) in a way that is favourable to the plans and objectives set out by the government and the command.”9 For the first time, psychology is officially classified as a combat weapon, making 1955 a pivotal year for France in the adoption of revolutionary warfare.10

The Web of Parallel Hierarchies

In 1956, following passage of the law granting special powers to the armed forces and the implementation of parallel hierarchies, an operational mechanism was established for counter-insurgency warfare that resembled in every way a true cobweb, whose net covered the entire Algerian territory. This ensured that the population was straddled, and that the enemy guerrillas became militarily and psychologically isolated.

The most important among the institutions that formed the parallel hierarchies was, no doubt, the Sections administratives spéciales (SAS) [Special Administrative Sections]. Singlehandedly, the SAS and the Sections administratives urbaines (SAU) [Urban Administrative Sections] were able to establish a new administrative zone, which, without eliminating the traditional districts, encompassed the latter. The SAS and the SAU constituted vital tools in revolutionary warfare, as they ensured the control and pacification, if not the indoctrination, of the population. To this end, they substituted themselves for the local authorities, carrying out functions in various areas, such as economic management, education, health, and government, with one SAS officer exercising all those responsibilities in each sector.11 The SAS network enabled the psychological services to keep close contact with the civilian population, and to spread their propaganda quite readily. Additionally, cooperation and psychological contact were maintained through other civilian organizations set up around isolated or neighbourhood leaders, who were under the auspices of the army. In the final analysis, the army, and, through it, the psychological war agencies, became present in the daily life of most of a population that gradually fell from under the influence of the FLN and the National Liberation Army.12

The Propaganda

In early 1956, the Bureau psychologique of the 10th Military Region decided to redefine and clarify its objectives. In an April Order, it established the following three-part mission: 1) maintain high morale among the units and protect them against the impacts of any enemy; 2) carry out a coherent psychological action with the Muslim populations in the operational areas; and 3) carry out a “shock” action against the rebels.13 Additionally, the territorial infrastructure associated with the psychological action was strengthened by the creation of revolutionary warfare tactical units known as compagnies légères de haut-parleurs et de tracts (CHPT), i.e. Light Companies armed with loud speakers and flyers. From July 1956, more effort was geared toward the development of propaganda targeted against the Muslim population already under French control. This propaganda had three dimensions: “A purely circumstantial dimension, a repetitive or overwhelming dimension,” perhaps “..[to] galvanize the Muslim population by giving them reasons to be enthusiastic that they could share with the French in Algeria and in the metropolis.”14 It was also intended to raise distrust among “neutral” Muslims toward the FLN, through messages such as: “Fellaghas are grasshoppers: everywhere they go, they leave nothing behind ...their trail is only littered with ruins, mourning, tears, starvation and misery.”15 It should be noted that this propaganda also targeted the rebel who was being tempted to renounce his support for the FLN cause. Finally, in order to incite the interest of neutral Muslims and to promote enemy exhaustion, the propaganda underlined the confidence that France placed in victory. For example, a psychological guidance note called for the use of the theme Certainty, Firmness, and Will.16 These same themes were concurrently being applied on the ground, in daily propaganda efforts.

le Bled

The loudspeakers of a mobile CHPT unit in action, circa 1957.

The Peak (January 1957-August 1958)

During the central period between January 1957 and August 1958, revolutionary warfare experienced a series of resounding successes, and it became an enabler in the emancipation and the political engagement of the army, whose increasing power in the face of a weakening regime led it to search for a rationale for its initial mission, namely, to keep Algeria within France.

The Recapture of the Kasbah: Triumph of Revolutionary Warfare

In January 1957, in order to crush the insurgent uprising in the Casbah in Algiers, the government granted full powers to General Jacques Massu, giving the army the power for which supporters of revolutionary warfare were clamouring. As noted by historians Field and Hudnut, “From that day, and until General De Gaulle firmly established the foundations for his powers, there were two governments in France.”17 Thus, this was a major turning point in the conflict.

Generals Lacoste, Salan and Massu drew up a battle plan and decided to launch the recapture of the Kasbah on 27 January 1957. In ten months, the army won the Battle of Algiers by methods based largely upon the parallel hierarchies, and upon revolutionary warfare, namely: intelligence acquired by any means, turnaround and manipulation of clandestine supporters, and management and control of the population.18 The regional Bureau provided General Massu with all the propaganda in written forms (pamphlets or leaflets) and spoken forms (loud speakers and movie theatre announcements), thereby playing a prominent role in thawing the situation in the Kasbah, and in breaking up the general strike. At the same time, territorial units, composed from 22,800 armed citizens, were established. Placed under the authority of a Colonel Thomazo, these units proved to be a valuable tactical tool of psychological warfare, with respect to information gathering, for propaganda dissemination, and for controlling the population.

This first major victory enshrined the revolutionary warfare doctrine and facilitated its maturity. For a second cadre of theorists, among them Colonels Trinquier, Godard, and Argoud, this war was no longer limited to applying a technique, as its political objective had become centralized and the Battle of Algiers offered the opportunity to experiment and to improve this new concept. According to Colonels Godard and Argoud, an effective fight against rebel terrorism should not exclude using counter-terrorism to create a psychological ‘shock.’19 For Colonel Argoud, who was stationed in Algiers as General Massu’s chief of staff, “The army must primarily seek to rally the population, to gain its confidence. It is the political dimension of the issue, and it is essential.”20. The modern warfare intelligentsia would then focus upon the question of a political mission for the armed forces. This view was based upon the certainty that the battle was being fought in order to keep Algeria within France. This certainty was then reaffirmed in the unequivocal themes of a proposal by the 10th Region Headquarters to the Regional Office: “France will remain in Algeria; Algeria will remain French; the government will not negotiate with the rebels; the declaration of intent of the Council’s Chair (January 1957) will be applied.”21

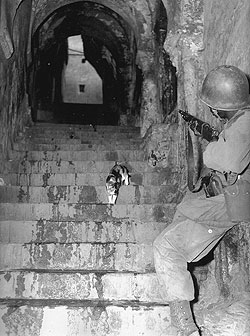

Archives militaires de France

Patrolling in the Kasbah, Battle of Algiers, 1957.

The Creation of the 5th Bureau and the Provisional Instruction TTA 117

In the aftermath of the Battle of Algiers, the French counter-insurgency war acquired further momentum through the creation of the 5th Bureau d’action psychologique,” established to accord the Seventh Weapon its proper importance within revolutionary warfare.”22 This new body was extended throughout the psycho-military infrastructure of the 10th Military Region: first, to the regional command, where, in the meantime, a new position of deputy chief of staff was created to complement the head of psychological action. It was also implemented in the army corps, where the psychological work was the responsibility of the 3rd Bureau, and, finally, in the various zones and operational areas. What should be particularly noted about the creation of the 5th Bureau is the significant extension of the army’s span of influence and control, since the new Bureau possessed, as of 1 August 1957, not only responsibility for all missions related to war and to psychological action, but also responsibility for morale, for information, and for civil and administrative matters, as well as for social services, and even the chaplain services. This “generalization” of its mission meant that the new body would have to become a true “Jack-of-all-trades” for the command.”23

This growing influence of the psychological weapon was, however, making civilian authorities uneasy, due to fear that it would lead to excesses in the long term. They therefore made every effort to limit as much as possible the scope of the 5th Bureau, as evidenced by the Bourgès Maunoury government’s adoption of the Instruction provisoire sur l’emploi de l’arme psychologique [Provisional Instruction on the Use of the Psychological Weapon], widely known simply as TTA 117.24 On the surface, the Instruction satisfied the wishes expressed by supporters of the revolutionary warfare by establishing a legal basis for the Seventh Weapon at the highest level. In reality, the civilian authorities were trying to underline the need for cooperation between the army and the government, where the latter necessarily prevailed.

In spite of its desire to regain the upper hand, the government had to recognize that revolutionary warfare had already made the army a true “State within a State”: “Throughout the land, departments’ borders became the same as those of an area controlled by a division, and district’s limits [became] aligned with those of a regiment’s sectors.”25 Moreover, the management priority of the population (education, social assistance, government) and psychological action (control of the media, information, propaganda) resulted in the delegation of the most extensive responsibilities to the armed forces, responsibilities normally assumed by the civilian authorities. In short, this military state held, so to speak, all the prerogatives of a civilian state, with one exception, that of making political decisions and developing an ideological line, on the strength of its parallel hierarchies. Gradually, this symbolic step will be taken with the establishment of what subject matter authorities K. Koonings and D. Kruijt called a “political army.”26

The Ideology of Integration, and ‘The Crossing of the Rubicon’

Having demanded from successive governments since 1956 that they be provided with a clear direction, and when they were offered nothing but vague and changing objectives, the army decided, in late-1957, to establish its own political doctrine: the ideology of Integration, born of revolutionary warfare. Opaque at first, it then crystallized upon the French Algerian theme, and its mission was based upon three fundamental objectives: to preserve French sovereignty, to extend full civil equality to Muslims, and to promote social and economic progress. The army was confident that such a program would enable it to counter both the FLN’s separatist aspirations and the civil authorities’ failure to act. For military leaders, emboldened by the absolute weapon that, to them, revolutionary war represented, Algeria became a personal issue that they expressed through that ideology. The objective sought by integration satisfied the need for the armed forces to establish a clear and straight-forward direction, something politicians had been unable to do.

At the same time as the army was acting, the national political entity, the 4th Republic, was on its deathbed: 15 April 1958 witnessed the fall of the Gaillard government, followed a week later by violent protests in Algiers in support of a French Algeria. The bell tolled for a dying regime, and the army, which became emancipated as a result of its political engagement, would administer the final blow by giving its support to General De Gaulle’s ascension to power, “...to implement the doctrine of revolutionary warfare.”27 The man considered by the French military to be their man would later prove to be the one to kill their political ambitions.

Archives militaires de France

General Jacques Massu

Neutralizing the Seventh Weapon (1959)

General De Gaulle’s Call to Order

From the moment he assumed power, De Gaulle was determined to subdue the army, which had become too outspoken and too intellectual for his liking. He was clear on the issue, and did not mince his words: “The army must realize that its role is purely technical. It is there to follow orders... The army is a tool. Get it? A tool!”28 Well aware of the potential of the psychological weapon, General De Gaulle also recognized the risk of ideologization it implied. He had therefore come to his decision long ago and on this he would not budge. He would save the army from all political aspirations.

From the fall of 1958, the army was ordered to renounce any political involvement. In the ensuing months, the President undertook a genuine purge within the French army, in order to rid it of any revolutionary tumour. To once again distinguish between civilian and military responsibilities, De Gaulle replaced Salan with two men: Paul Delouvrier was named the General Delegate, and General Maurice Challe, Salan’s deputy, was named Joint Supreme Commander. General Jouhaud became the Chief of the Air Staff, and many other generals and colonels were given positions in the Paris metropolis or in Germany. By the end of December, of all the senior leaders associated with the concept of Revolutionary Warfare and the Integration ideology, only General Massu and Colonel Godard remained, and only because they had been readily forgotten at the time.

The Challe Plan: A Reduced Role for the Psychological Weapon

Immediately after this cleansing exercise, De Gaulle undertook to significantly redefine the French army’s strategy by giving precedence to traditional warfare. He admitted that his objective was to obtain quick victories and to negotiate from a position of strength with the FLN. In reality, “De Gaulle had less evident motives to re-launch military activity: refocusing the military attention from politics to operations, and a resounding military success would enable the army to easily accept political concessions, their honour having been preserved.”29

In that vein, General Challe was asked to develop a battle plan that would refocus upon the good old traditional methods of warfare. The Challe Plan, however, retained an extensive number of the features of revolutionary warfare, particularly, the tactical aspects: to establish control of a territory, and to infiltrate enemy structures. The plan also called for the use of propaganda, disinformation, and intelligence, as in the past. The objective remained to bring the entire population under the control of the army, first, by tightening the borders, and second, by obtaining the engagement and cooperation of the Muslim masses. In particular, the new headquarters employed the psychological action methods developed by the 5th Bureau, which had been spared by the December purge. In fact, the 5th Bureau would remain a “nest” for the supporters of revolutionary warfare, as can be seen gleaned from the following excerpt from an article published in France’s Armed Forces Journal:

We have the responsibility to inform and to convince our bosses, our colleagues and our subordinates. If the army is not willing to understand that it needs to change its concepts and methods, it is heading toward failure in the immediate term and to its own demise in the near future, like an organization that is unable to change in a transformational environment. At this moment, we do not have the right to remain passive and indifferent. Moreover, each of us is “engaged,” whether we want to [be] or not.”30

As such, supporters of the Seventh Weapon expressed their disapproval of its gradual marginalization. In an article published in the May 1959 issue of Revue de Défense nationale, entitled “Considérations militaires sur la guerre d’Algérie,” [Military Reflections about the Algerian War] Jean Merye argued that without true psychological warfare, the new strategy employed by General Challe was irreversibly defective, and it had no change of success in the long term term.31 Colonel Antoine Argoud was of the view that the Challe Plan flowed from a faulty analysis of the issue, which placed emphasis upon the recapture of territory at the expense of the conquest of populations. In a book he will eventually publish in 1974 entitled, La décadence, l’imposture et la tragédie, he wrote: “General Challe knows revolutionary warfare only through books.”32

CMJ collection

Colonel Yves Godard

The Noose Tightens

In July 1959, a new Instruction appropriately entitled, Instruction sur les fondements, buts et limites de l’action psychologique [Instruction on the Foundations, Goals and Limits of Psychological Action] marked another step in the neutralization of the Seventh Weapon.33 The notion of psychological action had replaced that of psychological warfare, and it was now limited to boosting the soldier’s morale and to strengthening his will to fight. The themes espoused by this initiative were love of freedom, respect of people and their rights, preservation of the national identity, as well as promotion of fraternity and team spirit within the armed forces themselves. The Instruction also limited the responsibility of the army in psychological action by establishing a close collaboration between the political and military hierarchies. At the end of it all, the idea was to curtail significantly the political autonomy of the psychological weapon and to reduce its potential by reducing its role to that of a simple morale boosting enabler, as it had been before 1955.

It appeared that the 5th Bureau, the last bastion of revolutionary warfare, was spared by these measures. Its offensive and global role was even underlined in the psychological action plan for the months of November, December, and January. This document read in part: “Whatever forms our psychological action takes, whatever the methods used, they will be efficient if only all levels are aware of these two fundamental facts: 1) psychological action must be offensive, 2) psychological action must reach the individual through his morally and sociologically-defined environment (French of European stock, Arab, Kabyle, Muslim, Israelite).”34 However, this paradox is easily explained: If the 5th Bureau was asked by higher command to operate full speed and to contribute as efficiently as possible to the war effort, it was because senior leaders had decided to conclude the bothersome Algerian conflict, and come out of it with the best image possible under the circumstances.

Archives militaires de France

The barricades in Algiers, 25-27 January 1960.

From the Crisis to the Dismantling of the Revolutionary Warfare

Revolutionaries on the Barricades

On 16 September 1959, De Gaulle clarified his position by proposing self-determination, including the possibility of secession for Algeria. This constituted, in reality, the rejection of Integration and its supporters. As noted by scholars Doise and Vaïsse, “The statement by the Head of State marks the end of illusions and the beginning of the break-up between the Army for Algeria and the political power [...].”35 It is in this tense environment, where revolutionary warfare was once again rearing its head that the Barricades Affair occurred; an incident that would end the reprieve granted to the 5th Bureau.

In early 1960, the last group of Revolutionary Warfare proponents undertook decisive action. For a week, from 24 January to 1 February, a cadre of officers erected barricades on the streets of Algiers, with the help of French Algerian militants, in order to put pressure upon the government and to sway the authorities. Among officers supporting revolutionary warfare who took part in the Week of the Barricades, many, such as Colonel Jean Gardes, head of the 5th Bureau, as well as Colonel Argoud, occupied important positions in the army for Algeria, and did not hesitate to put their military careers at risk in order to defend a cause they felt was being threatened. Their action was also proof that they were willing to break the bond that had tied them to General De Gaulle since 13 May 1958. “It is from the barricades that advocates of revolutionary warfare tried to refute May 13, as they publicly and convincingly suggested overthrowing the De Gaulle government.”36

De Gaulle, who would not allow some “excited individuals” to dictate his policy or to question his sovereignty, quickly regained control of the situation. On 29 January, he delivered a televised speech while wearing his uniform, and ordered members of the armed forces to fall into line: “I am speaking to the army, who is winning in Algeria through brilliant efforts. Some of its elements however are ready to believe that the war is their war and not France’s, that they are entitled to have a policy that is not France’s. Let me say this to all our soldiers: “Your mission is neither equivocal nor does it require an interpretation.”37 Speaking to “isolated elements” that were conducting “their” war, according to “their” policy, De Gaulle was well aware that they were supporters of both Revolutionary Warfare and Integration. As historian Anthony Clayton later wrote, “De Gaulle rightly considered the incident an excess of the school of Revolutionary Warfare.”38 Now that this school has proved to all that it was a nest of factious revolutionaries, the general would seek to quickly destroy it. A significant number of its members would, however, be involved in events that would take place in April 1961.

Archives militaires de France

General Charles De Gaulle in Algeria.

The Disbandment of the 5th Bureau, the Conversion of the Seventh Weapon, and the Disappearance of Revolutionary Warfare

The 5th Bureau’s fate was played out at the barricades. “De Gaulle knew where the enemy was hiding in the army’s ranks. After the barricades, he could deal with it more efficiently.”39 He immediately decided upon a purging. Beginning in early February, events would happen very quickly. On the 1st of the month, the Head of State obtained the rendition of the Algiers insurgents; on the 2nd, an Act promulgated by the legislature which gave him the power to issue Orders and facilitated the purge; on the 3rd, the main leaders of Revolutionary Warfare knew what the purge entailed: Colonel Godard, Chief of the Security Services, was relieved of his duties, Colonel Argoud, chief of staff for the army corps, and Lieutenant-Colonels Broizat and Gardes, former heads of the 5th Bureau, were recalled. Finally, on the 5th of February, De Gaulle shuffled his Cabinet and got rid of Soustelle and Cornut-Gentil, both supporters of a French Algeria. After that, De Gaulle only had to deal with the main bastion of the concept of Revolutionary Warfare, that is, the 5th Bureau that, even without its main leaders, remained for the President the true culprit. It was ironic, therefore, that even as the 5th Bureau was being condemned, the first French atomic bomb exploded in the Algerian Sahara on 13 February 1960, providing the army with a weapon that was more psychological and more revolutionary than Revolutionary Warfare, namely, nuclear dissuasion.

On 15 February, the axe finally fell. De Gaulle took the official and irreversible decision to disband the 5th Bureau. A Directive issued the same day by the Ministry of the Armed Forces made the decision effective. General Demetz, the new chief of staff, wrote: “I would like to inform you that the organizations known as the 5th Bureau, which specialize in psychological action, will cease to exist upon receipt of this Ministerial Directive.”40 In addition, the official document stated that the 5th Bureau’s functions would be redistributed and added to those of various headquarters organizations. The dismembering of the 5th Bureau provided the opportunity to understand the immense power that had been obtained by this organization, and the extent of its influence within the armed forces. It would also be made clear why the political power, unable to deal with it, had waited so long before deciding to dismantle it. Through the Revolutionary Warfare years, the 5th Bureau had become the true ‘brain’ of the armed forces, in spite of efforts made to limit its autonomy (the 1957 Instruction), and action (the 1959 Instruction), providing guidance, coordination, and monitoring to the military.

After Revolutionary Warfare

With the dismantling of the 5th Bureau, Revolutionary Warfare as a concept no longer existed within the French army; nonetheless, a remnant of psychological action could still be found in a shattered form, no longer the purview of a single organization, but a shared responsibility among various services. The new decentralized system that emerged from April 1960 evolved around a Centre d’information générale et de problèmes humains [Centre for General Information and Human Issues]. It dealt with government information agencies and services, such as the Bureau Presse-Information [Media-Information Office]. From its inception, the new system, an obedient instrument following the will of the government, would support the policy of self-determination; it then helped prepare the ground for the Evian agreements and the independence of Algeria.

Revolutionary Warfare, along with the last of its supporters, went underground and became the fierce opposition to the politics of desertion in Algeria. The most hardened revolutionary warriors, notably Salan and Zeller, as well as Lacheroy and Argoud, would attempt the ill-advised April 1961 putsch, and then would join the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS) [the Secret Army Organization]. Their desperate actions could be viewed as the final manifestations of Revolutionary Warfare. Very quickly however, they were stopped by the political power that arrested them and brought them to justice. It would however take the final elimination of the last of those warriors, Colonel Argoud, on 25 February 1963, to seal the fate of Revolutionary Warfare that had been born six years earlier within the French army.

Archives militaires de France

Generals Salan, Challe, Zeller, and Jouhaud during the putsch of April 1961.

Conclusion

What lessons can be drawn from the Revolutionary Warfare experiment the French army conducted in Algeria? How can one explain its failure in spite of its contribution to the fight against the Algerian insurgency? Could it be that Revolutionary Warfare, as one could be tempted to instinctively conclude, was not made for a counter-insurgency force? As journalist Jean Planchais wrote, “How could this army, like its adversaries, live like ‘fish in the water’? From the outset, the system was impeded by not realizing that not all waters are good for all fishes. Everything after that was unreal. ...No psychology in the world, real or fake, could counter in the long run political and geographical facts that were impossible to change. A revolutionary war could only be a national war.”41 For the Pakistani writer, journalist, and anti-war activist Eqbal Ahmed, there is no doubt that western counter-rebellion theorists’ perception of Revolutionary Warfare is too mechanical, too removed from any concrete reality, and therefore not aligned with Revolutionary Warfare doctrine. “To them, the people represent a political object, a means rather than an end, a mass easy to mould and manipulate, whose behaviour... is more important than its feelings and its judgements. Focusing only on the operational advantages, counter-revolutionary analysis of the theory and the application of revolution tends to be superficial and doctrinal.”42

Yet, logic demands that the fighting occurs on the same battlefield as the enemy. In 1961, in an attempt to draw lessons from the French revolutionary war in which he was involved both as a theorist and a highly decorated practitioner, Colonel Roger Trinquier concluded in his famous book, entitled, La guerre moderne [Modern Warfare] the following: “In modern warfare... it is absolutely necessary to employ all the weapons our adversaries are using; not doing so will be absurd. We lost the Indochina war partly because we hesitated in taking the measures required or we took them too late.”43 More recently, observers of the global war on terrorism noted that the western coalition’s approach, which was primarily focused upon conventional effort, flowed from a false analysis of the psychological nature of the enemy fight, which gave the latter free reins on the information, public opinion, and the virtual mass communication front.44

It could also be argued that by definition, a counter-insurgency army, whose goal is to maintain the status quo, could not adopt Revolutionary Warfare as its method. It is, however, important to distinguish between Revolutionary Warfare and Revolutionary Ideology. Although early theorists and practitioners of this type of conflict, such as Lénine or Mao, were revolutionaries, other types of ideologies could espouse Revolutionary Warfare in order to achieve goals other than revolution per se. On this point, Raoul Girardet notes, “We could very well think of all forms of subversive war fought in the name of a purely national ideology, of liberal democracy or even of an ideal inspired by fascism.”45 In this regard, it is not a contradiction to think of Revolutionary Warfare as a method to be used in support of a counter-revolutionary war.

The issue is not, therefore, whether a counter-insurgency army could adopt Revolutionary Warfare, but how such an adoption would inevitably lead to the politicization of the mission. The political parameter is fundamental, for, as Mao Tse Tung, one of the fathers of Revolutionary Warfare explained, “A guerilla that has no political objective must fail.”46 If a counter-revolutionary army wants to control physically, but also and especially psychologically – which is more important in tje long term –, it must promote a political theme that is firmly established.47 That is the political dimension of Revolutionary Warfare, whatever its form: “The success of an anti-subversive war remains closely dependent on (or at least inseparable from) setting a public policy for rallying taking control of the population.”48 The political dimension is vital for gaining the population’s confidence, for influencing it, and for removing it from the enemy’s influence.

An anti-subversive war based upon Revolutionary Warfare rules, however, raises no doubt as to the sensitive issue of the politicization of the military – an unavoidable consequence of the establishment and promotion of an ideology. Persistently preaching something eventually leads to believing in it. Through politicization, the military seeks to have a say in the mission given to it by political authorities. A revolutionary force does not have this problem, since both political and military dimensions are meshed, but in the case of a democratic power involved in anti-subversive war, the issue could lead to a confrontation between the ideologized force and the legal authority, and it could result in a political crisis, such as the one France experienced from 1958 to 1961 during the Algerian war. As political scientist Maurice Duverger wrote: “An army which is prepared for subversive war... could not remain isolated from the nation, outside the politics... psychological warfare involves a political activity, a near-permanent intervention in the nation’s life.”49 This is a crucial dimension of Revolutionary Warfare.

CMJ collection

Poster for the highly rated 1966 film, The Battle of Algiers, written and directed by the Italian, Gillo Pontecorvo.

Beyond its limitations, the pioneering experience of the French military offers some lessons for today’s Fourth Generation warfare (4GW).50 History, which does not reproduce itself perpetually, does, however, repeat itself uncannily. At the dawn of the 21st Century, nations are engaged in an unusual war as they fight global terrorism. Governments, secret services, and military staff are faced with a huge challenge: fight a war with no front, no boundaries, and no identifiable enemy. The great powers are bitterly finding out to what extent their conventional and nuclear forces have little effect upon this elusive and determined enemy. They must adapt their fighting methods by being present on all fronts and by combining modern technology with old military tactics. To aggression and psychological harassment – a form of which is terrorism – they must learn again how to respond by psychological measures. This war, where intelligence and ingenuity trump the power of weapons, does have some advantages. It also entails some risks, which, hopefully, this study of the French experiment can help avoid.

![]()

Doctor Pierre C. Pahlavi is a Professor in the Department of Defence Studies, and Deputy Director in the Department of Military Planning and Operations at the Canadian Forces College, Toronto.

Notes

- Jean Planchais, Une histoire politique de l’Armée (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967), p. 321.

- François Géré, “Généalogie de la guerre révolutionnaire”, in La Guerre psychologique (Paris: Bibliothèque stratégique Collection, Economica, 1997), p. 15-45.

- General Beauffre, La guerre révolutionnaire. Les formes nouvelles de la guerre (Paris: Fayard, 1972), p. 50.

- Beauffre, p. 90

- Raoul Girardet, Problèmes militaires et stratégiques contemporains (Paris: Dalloz, 1989), p. 90.

- General L.M. Chassin, “Du rôle idéologique de l’Armée.”in Revue militaire d’information, No. 240, (October 1954), p. 13.

- Service historique de l’Armée de terre (SHAT). Military Archives, 1H 2403. Paris, March 1st 1955, Secretary of State for the Armed Forces “Land” – Cabinet, Morale Section. Note pour le 1er bureau de l’EMA – Objet : Création d’un organisme d’action psychologique. Signed by Colonel Drion on behalf of Army General Blanc, Army Chief of Staff.

- SHAT, 1H 2403 – Directive pour l’action psychologique sur le territoire de la Xe région militaire. Algiers, 27 July 1955 – General Lorillot.

- SHAT, 1H 2408 – Directive sur la guerre psychologique, Ministry of National Defence and the Armed Forces, Armed Forces Headquarters, Psychology Office. October 4, 1955. Signed by Koenig, Minister of National Defence and the Armed Forces.

- It became an all-purpose weapon in that it served both tactical and strategic purposes: “...tactical when it targets enemy units at the contact with the population behind the frontlines; ...strategic when it targets all enemy forces against one’s territory”; SHAT, 1H 2408.

- An example is provided in Alexander Zervoudakis, “A Case of Successful Pacification,” in Martin Alexander and J.F.V. Keiger, France and the Algerian War. Strategy, Operations and Diplomacy (London: Frank Cass, 2002), pp. 54-64.

- Paul Rich and Richard Stubbs, The Counter-Insurgent State. Guerilla Warfare and State Building in the Twentieth Century (New York: MacMillan Press, 1997), pp. 103-107.

- SHAT, 1H 2408 – Directive d’action psychologique. Algiers, April 1956. 10th Military Region, Psychology Office.

- SHAT, 1H 2403. Objet : renforcement des moyens de l’action psychologique pour l’Algérie et création de trois unités tactiques de guerre psychologique. Secretary of State for the Armed Forces “Land,” Army Headquarters, Cabinet, Psychology and Morale Section, 23 June 1956.

- SHAT, 1H 1117.

- SHAT, 1H 2408. Objet : Directives d’action psychologique – Note d’orientation 6 – 10th Military Region, Psychology Office Headquarters, Brigadier-General Tabouis, Chief of the Regional Psychological Action Office, on behalf of Army General Lorillot, Commanding Officer of the 10th Military Region, Superior Commander of the Joint Staff.

- Joseph Field and Thomas C. Hudnut, L’Algérie, de Gaulle et l’Armée (Paris: Arthaud, 1975), p. 36.

- General Paul Aussaresses, The Battle of the Casbah. Terrorism and Counter-terrorism in Algeria (New York: Enigma Books, 2002).

- They were on the other hand against using torture. See Guy Perville, “Quinze ans d’historiographie de la Guerre d’Algérie”, Annuaires de l’Afrique du Nord (Paris, Éditions du CNRS, 1976).

- Quoted in Planchais, p. 337.

- SHAT, 1H 2409. Schéma de causerie. Headquarters, Psychology Office, Action on the troops, February 1957.

- SHAT, 1H 2403. Secretary of State for the Armed Forces “Land,, Headquarters of the 1st Bureau. Objet : Création de 5e Bureau – Paris, 19 July 1957. Army General Lorillot, Army Chief of Staff.

- Planchais, p. 333.

- SHAT, 1h 2409. Ministry of National Defence and the Armed Forces. Instruction provisoire sur l’emploi de l’arme psychologique. Army General Ely, Chief of the Army General Staff, 29 July 1957, p. 77.

- Philippe Fouquet-Lapar, Histoire de l’Armée française. Paris: PUF, “Que-sais-je ?” Collection, 1986, p. 101.

- K. Koonings and D. Kruijt, Political Armies. The Military and Nation Building in the Age of Democracy (London and New York: Z Books, 2002).

- Anthony Clayton, Histoire de l’Armée française en Afrique – 1830-62 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1994), p. 225.

- Jean Doise and Maurice Vaïsse, Diplomatie et outil militaire 1871-1969 (Paris, Imprimerie nationale, Politique étrangère de la France Collection, 1987), p. 462.

- Clayton, p. 508.

- SHAT, 1H 2522 – Revue des Forces armées no 33. Excerpt selected by the Headquarters of the 5th Bureau in January 1959 to be distributed among officer and used as discussion theme.

- Jean Merye. “Considérations militaires sur la guerre d’Algérie”. Revue de Défense Nationale, Year 15, May 1959, p. 814.

- Antoine Argoud. La Décadence, l’Imposture et la Tragédie (Paris, Fayard, 1974). Quoted in Vaïsse, p. 463.

- SHAT, 1H 2410. Ministry of the Armed Forces, the Minister. Paris, July 28, 1959. Instruction – Objet : Fondements, buts et limites de l’action psychologique. Signed by P. Guillaumat , 5 pages.

- SHAT, 1H 2410. Algiers, November 7, 1959. Commander in Chief of the Forces in Algeria, Joint Headquarters, 5th Bureau. Plan d’action psychologique pour les mois de novembre, décembre et janvier.

- Doise and Vaisse, p. 464.

- Field and Hudnut, p. 132.

- Quoted in Doise and Vaisse, p. 466.

- Clayton, p. 228.

- Field and Hudnut, p. 148.

- SHAT, 1H 2403, Paris, 15 February 1960, Ministry of the Armed Forces “Land”, Army Headquarters, 1st Bureau, on behalf of the Minister and by delegation, General Demetz, Army Chief of Staff. Objet : dissolution des 5es Bureaux.

- Planchais, pp. 338-339

- Eqbal Ahmed, “Guerre révolutionnaire et contre-insurrection”, in Gérard Chaliand, Stratégies de la guérilla – Anthologie historique de la longue marche à nos jours. Paris, Gallimard, Idées Collection, 1984, p. 244.

- Roger Trinquier, La guerre moderne. Paris: La Table Ronde, 1961, p. 187.

- John Mackinlay, Defeating Complex Insurgency: Beyond Iraq and Afghanistan. London: The Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, 2005; Bard O’Neill, Insurgency and Terrorism (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005).

- Girardet, p. 94

- Quoted in Field and Hudnut, p. 43.

- Eric Wolf, Peasant Wars in the Twentieth Century (New York: Harper Torchbook, 1969), p. 244. Also see US Army Staff College, Counter Revolutionary Warfare and out of Area Operations Handbook, Army Staff College, 1985, p. 16.

- Girardet, p. 113.

- Field and Hudnut, p. 42.

- See Colonel Thomas X. Hammes, The Sling and the Stone. On War in the 21st Century (St-Paul, MN: Zenith Press, 2004).

The barricades in Algiers, 25-27 January 1960.