This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

The War Against Terrorism

Associated Press 810112016

Afghan guerrillas atop a downed Soviet MI-24 helicopter, January 1981.

Jihad versus Global War on Terror (GWOT) – A Total War in the Making?

by Dwayne Lovegrove

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Nearly a decade of attacks made by Islamic terrorist and insurgent organizations against the United States and its allies culminated with the events of 11 September 2001. Having previously called for ‘jihad’ against the ‘Great Satan,’ al Qaeda audaciously delivered its most deadly blows to date with a triple attack against the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and (presumably intended) the White House. In response, the United States has led and sponsored a worldwide campaign of retributive and pre-emptive attacks in various theatres, conducted under the universal title of ‘Global War on Terror,’ popularly termed as ‘GWOT.’ There are increasing signs that the confrontation between Jihad and GWOT is having an impact on the full spectrum of society, with concomitant military, economic, political, technological, legal, religious, social, and psychological ramifications. As world headlines darken with accounts of increasing casualties and expanding brutality, some have suggested that the current conflict between the forces of Islamic fundamentalist extremism and American-sponsored liberal democracy constitutes the possible advent of total war.

The idea that rising global terrorism may constitute ‘World War IV’ is not new, having been first proposed by Alexandre de Marenches, a former head of France’s external intelligence agency, in 1992.1 More recently, support for the ‘World War IV’ moniker has gained popularity, particularly within neo-conservative circles, as the current conflict has progressed and expanded.2 Opponents who argue that the conflict constitutes limited war at best are hindered by the lack of a universally accepted definition of total war.

In this light, I have chosen to use a model that utilizes three categories of distinguishing total war characteristics.3 First, the scope of violence directed against both combatants and civilians will consider the number of casualties, technology and innovation, lethality of weaponry, extremes of methodology, and geographic scale. Next, the mobilization of society will link to such indicators as civilian engagement (including conscription and recruitment), economic and industrial impacts, societal change, and propaganda. Finally, the objectives of the war will refer to the extremity of war aims and objectives, including vital interests and defining ideologies. Given space constraints, I have chosen to limit the task by using al Qaeda to represent the Jihadist movement, and the United States as the focus for the GWOT. A brief review of their respective compositions and policies hopefully will provide a useful starting point.

David Stewart-Smith/Associated Press 8701010459

An Afghan guerrilla sights an American-made Stinger missile, circa November 1987-January 1988.

Background

Enigmatic by design, al Qaeda al-Sulbah (‘The Solid Base’) was founded as ‘Mujahidin al-Arab’ in 1984 to fight the Soviet presence in Afghanistan. It has since created the “World Islamic Front for Jihad against the Jews and the Crusaders” in a bid to establish ideological, political, financial, and military control over a wide range of terrorist and insurgent groups. Seeking to broaden its organization in response to American GWOT successes, al Qaeda has renounced attacks against Shi’ites in a bid to unite anti-American Islamic radical groups, and now purportedly works with criminal organizations in mutually beneficial alliances. The US government also insists that al Qaeda enjoys support from Syria, Iran, and the Hamas government of the Palestinian Authority, as well as the complicity of many other Middle Eastern nations.4

While Osama bin Laden is well-known as the principal architect and leader of al Qaeda, those who comprise the mainstream of the organization are not. Contrary to popular Western perceptions, the majority of Jihadists from the Middle East region are mainstream middle class professionals, often engineers or other university- or college-educated people, and they are married. Most of al Qaeda’s fighters live in the Muslim diaspora, and join the Jihad outside their country of origin. Significantly, most are not recruited, instead normally enlisting through ties of friendship and family.5 Prior to the American-led counterattack, training was conducted in Afghanistan and other globally dispersed camps, where as many as 110,000 fighters were trained between 1989 and 2001 alone.6

Denny Cantrell/Defense Imagery.Mil 080227-N-8157C-225

Shi’a and Sunni Muslims make their way to the Imam Husayn Shrine in Kabala, Iraq, 27 February 2008.

Despite being fragmented by the GWOT, al Qaeda continues to act successfully as a ‘force multiplier’ by providing experts, trainers, and funds to other groups, operating effectively and efficiently through its associates. Principally established in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, Southwest and Southeast Asia, and the former Soviet republics in the Caucasus, al Qaeda is also believed to have cells in approximately 60 countries worldwide. Unlike previous Islamic-based terrorist groups whose attacks were usually localized events with limited national objectives, al Qaeda sponsors and leads a transnational, global insurgency. Credited for the original 1993 attack on the World Trade Center, some of the more notable attacks widely accepted to have had al Qaeda involvement include the 1996 bombing of the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, the 1998 attacks on US embassies in Africa, and the 2000 attack on the USS Cole. Although it has not struck the United States since 2001, numerous other countries have since become victims of significant attacks linked to al Qaeda and its associates. Despite being labelled as ‘terrorists’ by US policymakers, al Qaeda’s demonstrated preference to strike military, economic, and political targets suggests a Maoist-style strategy of guerrilla insurgency conducted on a global scale. Osama bin Laden’s warning to Americans of his intention to “...target the key sectors of your economy until you stop your injustice and aggression...” clearly support this argument.7

Tapping into long-standing Islamic cultural frustrations and humiliations, al Qaeda’s ideology seeks to exploit the perception that the once-proud Muslim culture has become poor and weak, due to centuries of military, economic, and political losses against Western imperialist invaders.8 Akin to the ancient Crusaders, the United States is accused of exerting oppressive hegemonic influence over the Islamic world. Muslims resent American support to the corrupt, repressive, authoritarian Middle Eastern regimes that exploit them, as well as its support to Israel, which occupies Jerusalem, the third-most important holy place for Muslims.

Al Qaeda also seeks to exploit religious differences rooted in the very beginnings of Islam and Christianity. Since Mohammed was both a prophet and a ruler, secularism is foreign to Islam. As such, espousing democracy appears to Islamic fundamentalists to be a direct attack upon the basic tenets of their religion.9 This has allowed al Qaeda to claim that the United States is fighting a religious war, convincing many to “...sincerely believe that the West and primarily the United States represents a mortal danger to Islam... (that) must be converted or destroyed.”10 In his subsequent declaration of war against the United States, Osama bin Laden made jihad an imperative for all good Muslims worldwide:

We – with God’s help – call on every Muslim who believes in God and wishes to be rewarded to comply with God’s order to kill the Americans and plunder their money wherever and whenever they find it. We also call on the Muslim community, leaders, youths and soldiers to launch the raid on Satan’s US troops and the devil’s supporters allying with them and to displace those who are behind them so that they may learn a lesson.11

In an address to the US Congress replete with total war rhetoric, President George W. Bush responded to the 11 September 2001 attacks by declaring war on al Qaeda in return, promising to “...direct every resource at our command – every means of diplomacy, every tool of intelligence, every instrument of law enforcement, every financial influence, and every necessary weapon of war – to the disruption and to the defeat of the global terror network.”12 Military and security operations immediately began at home, while overseas, the United States led multinational military forces, first against Afghanistan, then against Iraq. Responding to President Bush’s call for a “...global campaign of unprecedented scale and complexity” against terrorism, some 136 countries offered a wide range of military assistance, with a total of 27 nations directly contributing troops to one or both theatres of operation.13

Diplomatic efforts to expand and formalize international support for a ‘Global War on Terrorism’ quickly followed. The North American Treaty Organization (NATO) responded immediately, and it continues to participate in the GWOT through the deployment of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, and through Operation Active Endeavour in the Mediterranean. Backed by several United Nations Security Council Resolutions, the United States created numerous international subset partnerships, including the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), the Broader Middle East and North Africa (BMENA) initiative, and the Anti-Terrorism Assistance (ATA) program. As a ‘Group of Eight’ member, even Russia agreed to join in the fight.

Jerry Morrison/Defense Imagery.Mil 080703-F-6655M-003

President George W. Bush, 3 July 2008.

Similarly, the US leads numerous combined military operations, the most significant of which are Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq. As of September 2006, the United States had over 232,000 military personnel deployed in these two venues alone, its largest deployment of troops since the Vietnam War.14 The former figure does not include Special Operations personnel, who are fully engaged worldwide in the complete spectrum of GWOT activities, including Unconventional Warfare and Psychological Operations.15 In January 2007, a ‘surge’ of 21,500 additional personnel in Iraq was added, along with a permanent strength increase in the Army and Marine presence of 92,000.16 Still, with some units beginning their third rotation into Iraq despite having activated the Reserves, there are many who question the US military’s ability to sustain GWOT operations at their pre-surge levels.

The actions taken by the United States reflect the concepts of its new National Security Strategy released in September 2002, popularly known as ‘the Bush Doctrine.’ Essentially, the new doctrine abandoned the concepts of Cold War deterrence in favour of a forward-deployed, pre-emptive strategy against rogue states and terrorist groups. Characterized by a ‘good-versus-evil’ moral justification, the Bush Doctrine espouses the use of regime change to eliminate political oppression, the right to use pre-emptive attack to prevent attacks on the US, and support for the creation of a democratic Palestinian state as the ultimate solution to Middle Eastern discord.17

Supporting the National Security Strategy, the National Strategy for Combating Terrorism provides the overall GWOT plan. Its revised version emphasizes pre-emptive action against terrorists, preventing the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), and ‘draining the swamps’ by eliminating physical, legal, cyber, and financial safe havens for terrorists. As “...the long-term antidote to the ideology of terrorism,” the strategy seeks the “advancement of freedom and human dignity through effective democracy.”18

Defense Imagery.Mil DD-ST-86-06668

Afghan resistance fighters return to a village destroyed by Soviet forces.

With the acknowledgement that “the War on Terror will be a long war,” the revised policy has added the objective of re-establishing and/or strengthening “...an array of domestic and international institutions and enduring partnerships” as were those created to win the Cold War. With the goal of setting and maintaining international standards of accountability, the United States has succeeded in having 12 universal conventions and protocols decreed by United Nations, including obligations on states to improve border controls, to suppress and prevent terrorist financing, recruitment and sanctuaries, and to enhance information sharing and law enforcement cooperation.19

Internally, efforts have been made to enhance interagency cooperation through the creation of such entities as the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Of particular importance is the USA Patriot Act of 2001, which gave government and law enforcement bodies greatly expanded powers for surveillance, investigation, search, and arrest. On the military side, Northern Command (NORTHCOM) was created to coordinate military aspects of homeland security, while the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) was significantly expanded in what the US Government calls its “...largest rearrangement of its global force posture since the end of World War II.”20

Cultural and civil defence aspects have not been overlooked. Aimed at “...fostering intellectual and human capital,” the new policy seeks ways to “...create an expert community of counterterrorism professionals” through the National Security Language Initiative and other such education- and culture-based activities. More significantly, it also seeks to foster a ‘Culture of Preparedness’ for all elements of American society, extending from the federal government down to the private sector and individual citizens.21

As the GWOT has expanded, so have its incumbent liabilities. In particular, victory in Iraq has become a vital US interest, as failure would both provide a safe haven for future terrorist attacks and would represent a victory for terrorism, calling into question American credibility and commitment to the Middle East and world security. US policymakers warn:

...[that] Middle East reformers would never again fully trust American assurances of support for democracy and pluralism in the region – a historic opportunity, central to America’s long-term security, forever lost... If we retreat from Iraq, the terrorists will pursue us and our allies, expanding the fight to the rest of the region and to our own shores.22

The Scope of Violence

With such high stakes, has the conflict reached total war proportions? In terms of the scope of violence involved, an easy measure might be the number of military and civilian casualties, but there are few definitive information sources available. Much of the difficulty lies in the fact that there appear to be three concurrent conflicts ongoing in Iraq. Even when using US military statistics, it is impossible to separate out casualties intentionally caused by Jihadists, as opposed to those inflicted by remaining Baathist supporters or as a result of Sunni-versus-Shia strife.23 Relatively recent (April 2007) US military statistics put casualties in both Iraq and Afghanistan at 3672 killed and 25,941 wounded for US forces alone, and that number has increased significantly in the ensuing 18 months.24 Civilian casualties are even harder to ascertain, with a conservative estimate of over 67,000.25 Some pundits consider these numbers to be far too conservative, citing combined military and civilian casualties as high as 2.2 million.26 Both protagonists have accused the other of deliberately targeting civilians. More than an estimated 4.5 million refugees have fled these two nations, including up to 40 percent of the Iraqi middle class.27

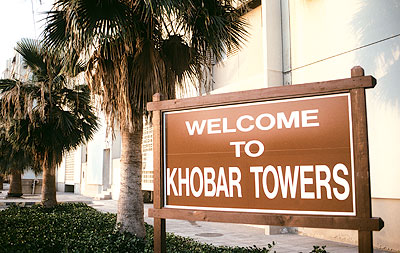

Sean Worrell/Defense Imagery.Mil DF-ST-99-10406

The Khobar Towers complex before…

Sean Worrell/Defense Imagery.Mil DF-ST-99-10408

And after…

The influence of advanced technology and innovation is far clearer, with numerous examples on both sides. The Jihadists have successfully combined elements of advanced technology, globalization, innovation, and Western freedoms to their advantage. While many might consider al Qaeda’s ‘weaponization’ of a hijacked airliner as its most dramatic ‘technical surprise,’ it is not its most significant ‘surprise.’ No longer a ‘weapon of last resort,’ as they were utilized in previous total wars, al Qaeda regularly employs suicide bombers. Although their incidence constitutes less than five percent of terrorist events, they have accounted for roughly half the casualties inflicted upon US and coalition forces.28 Al Qaeda’s primary weapon of choice is the improvised explosive device (IED) in increasingly-sophisticated forms, including remotely-controlled and vehicle-borne variations. In widespread use, their defeat continues to pose a significant technological challenge. Al Qaeda makes extensive use of the Internet for transmitting doctrine, tactics, and procedures to its adherents. More sinister is al Qaeda’s attempts to gain access to and use WMDs, as well as the means for their delivery. Jihadists have conducted experiments with rudimentary chemical weapons teamed with crop spraying aircraft, and are suspected to have recently employed crude chlorine-based weapons in Iraq.29

Yet another technological surprise has materialized with al Qaeda’s development into a ‘leaderless resistance.’ Further exploiting advanced technology, al Qaeda makes extensive use of laptops, satellite telephones, and encrypted communications websites for passing hidden messages. This has allowed the organization to operate through regional bureaus as nodal points in a dispersed, horizontal hierarchy that cannot be defeated simply by eliminating its more prominent leadership figures.30 Other examples of al Qaeda ingenuity can be found in its financial and information operations. Following actions taken by the United States to freeze its financial assets and restrict its ability to raise money, al Qaeda reportedly has resorted to cooperative agreements with criminals and drug smugglers. It has transformed its banking practices so that now it gets much of its money through ‘hawala,’ a system of unregulated, underground banking networks.31 Taking advantage of the Internet, the liberal Western press, and sympathetic media outlets such as Al Jazeera, al Qaeda operates an extensive information campaign to target public opinion, expanding its popular support while simultaneously spreading fear and doubt among its adversaries.

The list of technological innovations being put into widespread use for the first time by the United States is extensive. Perhaps the most dramatic surprise has come with the US military’s proven ‘Time Sensitive Targeting’ capabilities, making it possible to successfully detect, locate, and bomb an individual on the basis of a cellular phone conversation. Other innovations include space-based communications tracking, IED jammers, and the widespread use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to search, to monitor, and even to attack. Millimetre wave, acoustic, and ultra-violet devices are in use for detecting concealed weapons, while biometric facial recognition systems are being employed to identify known terrorists.

To counter al Qaeda’s extensive use of the Internet, the United States has made the first significant, publicly-acknowledged use of cyber-surveillance and warfare. Considerable privacy concerns were expressed when the existence of CARNIVORE, an Internet- based counterterrorism tool, was made public. Official security agencies reportedly also make extensive use of Internet-based surveillance systems for detecting and tracking possible use of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons by monitoring on-line medical records.

Unfortunately, extremes of violence have been employed by both sides in this conflict. Beyond its use of passenger airliners as weapons, al Qaeda has horrified many with the publicized beheading of prisoners, the use of women and children as suicide bombers, and the employment of rudimentary chemical weapons. The GWOT has also employed ‘extreme’ measures, using precision-guided bombs to attack individuals, along with other examples of overwhelming firepower. Tellingly, the largest conventional bomb ever produced, the 21,000 pound GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast bomb (MOAB, nicknamed the ‘Mother Of All Bombs’), was developed for use in Afghanistan. Also seen by many as an extreme methodology is ‘extraordinary rendition,’ where captured prisoners are surreptitiously delivered to third-party countries where torture is reportedly used.32 The abuses that occurred at the Abu Ghraib prison and the prolonged detainment without trial of ‘unconventional prisoners of war’ at Guantanamo Bay have been strongly denounced by many. Perhaps the most significant and yet overlooked aspect in the scope of violence has been the use of women in combat by both sides.

USN photo/Defense Imagery.Mil 00914-N-0000X-001

The USS Cole in its natural element.

Aladin Abdel Naby/Reuters RTX71G8

Port side of USS Cole after the terrorist attack in the port of Aden.

The Mobilization of Society

In considering the mobilization of society, the central importance of culture in the conflict cannot be understated. Al Qaeda’s centre of gravity is Islam, allowing it to be “...intertwined in the socioeconomic, political and religious fabric of Muslims living in at least 80 countries.”33 Al Qaeda’s religion-based message has gained them widespread support from within the radical elements of the global Islamic community, while muted condemnation from western Islamic communities reflects, at the very least, silent sympathy. Often, actions taken by the GWOT to counter al Qaeda operations only serve to fill the latter’s ranks.

In the United States, appeals to common values are used to keep public support alive, citing “Freedom [as] the non-negotiable demand of human dignity; the birthright of every person – in every civilization.”34 Negative messages, such as ‘Terror Alerts,’ have also kept the civilian sector engaged, along with media coverage of caskets returning home. Patriotic ‘yellow ribbon’ campaigns and ‘Support Our Troops’ bumper stickers, designed to unite citizens and to facilitate recruiting, represent signal civilian engagement reminiscent of pre-Vietnam War America.

To this point, economic indicators have not reached total war proportions, although they are becoming more evident. The partnership between global terrorism and the drug trade undoubtedly has had deleterious effects worldwide. While opium suppliers stand to reap record profits, the destruction of Afghan poppy fields as a secondary GWOT mission directly impacts the prosperity of impoverished farmers, and it serves to generate animosity towards Coalition forces. It is estimated that one-fifth of Islamic Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and charities have been penetrated by al Qaeda, siphoning funds away from legitimate refugee relief efforts.35 The freezing of funds by the United States has had impacts worldwide, as some legitimate companies are undoubtedly affected. Beyond the financial losses, the ‘brain drain’ of educated middle class professionals from Middle Eastern nations to jihad has probably had a similar yet suspected detrimental effect upon the future of those nations.

Peter Andrews/Reuters RTX5XVD

A Canadian soldier from 3 Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (3PPCLI), patrols in a poppy field in the Zharey District, southern Afghanistan, 20 May 2008.

In the United States, President Bush’s promise to use “all elements of national power” is beginning to make itself felt. In terms of defence spending alone, the total 2008 funding request is $623.1 billion; more than double the 2001 US defence budget of $311 billion. Naysayers emphasize that this only represents roughly four percent of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which pales in comparison to that of the Second World War (34.5 percent), or even the Vietnam War (nine percent).36 In response, many critics point to the impending ‘rust out’ of military equipment and the rising cost of veterans’ benefits as just two of the more significant looming costs of the war. As a specific example, there are nearly 42,000 light trucks in Iraq alone that will soon need to be replaced.37

The impact of the war is felt more immediately by the average American citizen. Many believe the cost of living has gone up appreciably, due to rising fuel prices and increased security measures, the burden of which are passed on to consumers. Besides trade, the conflict has had a significant negative impact upon commercial air travel, insurance, and tourism.

The Changes in Society

What may be more significant are the changes in society wrought by the conflict. Ironically, in order to counter al Qaeda’s exploitation of western democratic freedoms, the United States has had to restrict them at home while simultaneously espousing their virtues to the Muslim world. The sweeping powers enshrined in the USA Patriot Act have raised concerns among many citizens about their privacy, rights, and freedoms. The psychological impact of the National Strategy’s ‘Culture of Preparedness’ has also been significant, as the constant barrage of threat warnings has created a culture of fear among many Americans. While suggestions of ‘wrapping one’s house in cellophane’ as protection against chemical attack may seem humorous, the extent of civil defence precautions strongly suggests a nationwide siege mentality. Billions of dollars have been spent on a wide range of domestic defences, including border security, radiation monitoring, biological surveillance, stockpiling vaccines and antibiotics, and protection for critical infrastructure, such as chemical facilities, dams, and nuclear power plants.38

Despite efforts, heightened cultural tensions between Muslims and their various neighbours throughout the world have been inevitable, making Samuel Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’ prediction appear plausible. Cartoons published in a Danish newspaper led to widespread rioting by Muslims, effectively ensuring their continued distribution as a counter-reaction. Public opinion has polarized, with restrictions being placed against headscarves (hijab) in some locations. Multiculturalism has come under critical scrutiny as ‘home-grown’ Islamic terrorists have come to the fore in several western countries, including Canada. The unrest has served to arouse greater public indignation and radicalization on both sides. For many, it has also led to ‘issue fatigue,’ with ever more frequent civil protests being driven by rising costs and increasing casualties.

Propaganda has clearly played a key role in the conflict. Either through the shocking use of airliners as weapons, or through a ‘Shock and Awe’ campaign of massive bombing, both sides have sought to score psychological blows. According to al Qaeda, President Bush is “...the Pharaoh of this day and age,” leader of “...the gang of criminals in the White House... the biggest butchers in history.”39 Urging attacks against Americans, Osama bin Laden has accused the United States of making “a clear declaration of war on God, his messenger, and Muslims.”40 Similarly, President Bush has sought the moral high ground, telling Americans, “...[that] we are in a conflict between good and evil, and America will call evil by its name.”41 American neo-conservatives have demonized Jihadists as ‘Islamofascists,’ and playing cards depicting Iraqi leadership figures have been used to promote a ‘dead or alive’ campaign.

Mahmoud Raouf Mahmoud/Reuters RTR21014

A man grieves at the site of a bomb attack in Baghdad, 25 August 2008, which killed 25 people.

The Objectives of War

When considering the stated objectives of war, one finds the strongest evidence of total war in the making. Above all else, the conflict is a war of ideas, a crucial struggle for the hearts and minds of Muslims worldwide in what some have termed “...the battle for strategic influence.”42 The ideological confrontation between democracy and Islam threatens to be a zero-sum struggle between secularism and fundamentalism, as both are diametrically opposed to each other, and there is little or no apparent middle ground available. As a result, the vital interests of parties are at stake. Al Qaeda’s demands to “purge the holy lands of infidels” in order to create an idealist’s caliphate represent the antithesis of Western liberal democratic freedoms and values. Discrediting this concept is part of official US policy.43 The United States has little choice, as even its harshest critics admit that changing its Middle Eastern policy or removing US troops will not make al Qaeda go away.44

In terms of ultimatums, there are plenty to go around, since both sides have given their prospective allies ‘all or nothing’ choices. President Bush warned, “...[that] every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”45 For his part, Osama bin Laden decreed,

[that] the one who stays behind and fails to join the Mujahidin when jihad becomes an individual duty commits a cardinal sin... the most pressing duty after faith is repelling the aggressor enemy. This means that the nation should devote its resources, sons, and money to fight the infidels and drive them out of its land.46

In a statement reminiscent of the Second World War demand for ‘unconditional surrender,’ President Bush replied: “Against such an enemy, there’s only one effective response: We never back down, never give in and never accept anything less than complete victory.”47

To be expected, there is no consensus among analysts whether the current conflict portends total war. While dissenters discount the GWOT as something that “bears more resemblance to a protracted hunt,” or “muscular police work,”48 almost all agree that the situation represents a significant threat to America’s national well-being. In terms of ideology alone, there is sufficient evidence to argue that a total war currently exists, with two diametrically opposed dogmas facing off in an ‘all or nothing’ contest. Despite recognizing that both the source and resolution of the conflict lie in cultural issues, both sides continue to pursue a solution through mostly violent means, with neither side willing to budge amidst dire predictions should they fail.

The mobilization of each respective society is still limited, but growing. Although both leaders have publicly declared their intentions to use all available resources, economic and civilian sectors are not yet fully engaged in or impacted by the war. However, both sides recognize that the ‘hearts and minds’ of their home audience represent their respective centres of gravity; therefore, greater engagement of the civilian sector is likely. The repercussions of another major attack in North America could easily tip the balance towards greater economic and social mobilization, especially if it involves WMDs.

Seemingly having little to lose, al Qaeda has proclaimed its willingness to continue the conflict until it is resolved in its favour. However, many analysts believe that the United States is rapidly approaching a crisis point, as current US troop levels in Afghanistan and Iraq are unsustainable in the long term. Even if all other Western nations were to make significant military contributions, it is unlikely that their combined contributions could match the deployed strength and effectiveness of the US military. Given the incipient ‘burn out’ of its troops, the United States may soon have little choice but to increase its engagement by reinstituting limited Selective Service, not only to sustain its current war effort, but to expand it enough to achieve its extensive policy objectives. The alternative would mean withdrawing a large portion of its forces for reconstitution, effectively surrendering some areas to a Vietnam-style fate.

Similarly, after five years of heavy use, entire fleets of military equipment are approaching ‘rust out’ and will soon have to be replaced. Fulfilling its equipment needs may draw the US closer to the mobilization of its defence industries. Imposing a considerable financial burden even for the United States, this will likely require an even greater portion of the GDP, along with a commensurate increase in borrowing and national debt, all of which can be expected to have undeniable impacts upon the nation’s economic health. Thus, in terms of mobilization, the United States is rapidly approaching a decision point that may lead the nation toward a total war footing.

Defense Imagery.Mil DD-ST-88-09407

An Afghan Mujahideen demonstrates the positioning of a hand-held surface-to-air missile.

Conclusion

While the scope of violence has yet to approach that of traditional total war, it is considerable and widespread enough to produce psychological and societal effects of a ‘nearly worldwide’ scope. Should al Qaeda gain access to and use WMDs, massive civilian casualties are likely to be forthcoming. Even without WMDs, another significant attack in the United States would likely ignite a major popular backlash against Muslims, perhaps globally. The irresistible demand for retribution could push the United States government toward even greater mobilization and extremes of response. Of note, US government officials have never ruled out the use of nuclear weapons. As actions exacerbate reactions, the conflict is likely to expand, both in scale and savagery.

In the end, does it really matter whether we consider this war to be ‘total’ in nature? Total war is often characterized by a gradual radicalization and abandonment of restraints. Thus, while only some total war indicators may be present currently, the possibility exists that the conflict may grow to possess all of its terrible characteristics. In contrast, resolution of this conflict will likely require a ‘total’ response that may result in lasting political, economic, and social changes to both the Muslim nations and the larger ‘Western’ world. The outcome remains to be seen.

![]()

Major Dwayne Lovegrove, a pilot, is currently Task Force Commander of Operation Gladius, Canada’s contribution to the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) in the Golan Heights. A veteran of several deployments to the Middle East, he was recently employed in the International Plans directorate of the Strategic Joint Staff in Ottawa, while simultaneously completing a Master’s degree in War Studies at the Royal Military College of Canada.

Notes

- Alexandre de Marenches and David Andelman, The Fourth World War: Diplomacy and Espionage in the Age of Terrorism (New York: William Morrow, 1992).

- Examples include Norman Podhoretz, “World War IV: How It Started, What It Means, and Why We Have to Win,” in Commentary, September 2004, pp. 17-54, and Andrew Bacevich, “The Real World War IV,” in Wilson Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Winter 2005), pp. 36-62.

- The three-point model being used is derived from that proposed by William R. Hawkins, “Imposing Peace: Total vs. Limited Wars, and the Need to Put Boots on the Ground,” in Parameters, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Summer 2000), pp. 72-82.

- George Weigel, “Just War and Iraq Wars,” in First Things: The Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, April 2007, p. 16.

- Scott Atran, “Global Network Terrorism: Sacred Values and Radicalization; Comparative Anatomy and Evolution,” Briefing to the National Security Council, White House, Washington DC, 28 April 2006, pp. 40-42.

- Rohan Gunaratna, Inside Al Qaeda: Global Network of Terror (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 7.

- Osama bin Laden, audiotape broadcast on Al Jazeera, 6 October 2002, as cited in Gunaratna, p. xvii.

- Bernard Lewis, “What Went Wrong?” in The Atlantic Monthly, January 2002, pp. 43-45.

- Bernard Lewis, “Islam and Liberal Democracy: A Historical Overview,” in Journal of Democracy, Vol. 7, No. 2 (1996), pp. 52-63.

- Thomas H. Johnson and James A. Russell, “A Hard Day’s Night? The United States and the Global War on Terrorism,” in Comparative Strategy, Vol. 24, No. 2 (April – June 2005), pp. 136-137.

- Declaration of war by Osama bin Laden, as cited by Gunaratna, p. 1.

- President George W. Bush, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People,” United States Capitol (Washington DC: White House Press Secretary, 20 September 2001).

- United States, Department of State, Patterns of Global Terrorism 2001 (Washington DC: Department of State, May 2002), p. xii.

- United States Department of Defense, Defense Manpower Data Center. Statistical Information Analysis Division (SIAD), “DoD Military Personnel and Casualty Statistics,” Chart depicting “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country – September 30, 2006.”

- US Special Operations Command (US SOCOM), Global War on Terror (GWOT)/Regional War on Terror (RWOT), Operations and Maintenance, Defense Wide Budget Activity 01, FY 2007 Supplemental Request.

- Amy Belasco, CRS Report for Congress: The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11, Congressional Research Service, Updated 14 March 2007, pp. 35-36.

- Podhoretz, pp. 25-34.

- United States, Department of State, National Strategy for Combating Terrorism, The White House (Washington DC: Department of State, September 2006), pp. 1, 9.

- Ibid, p. 19.

- Ibid, p. 20.

- Ibid, p. 21.

- United States National Security Council, “National Strategy for Victory in Iraq,” The White House (Washington DC: National Security Council, 30 November 2005), p. 6.

- Weigel, p. 15.

- United States, Department of Defense, Defense Manpower Data Center, Statistical Information Analysis Division (SIAD), “DoD Military Personnel and Casualty Statistics,” Chart depicting “Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom Casualty Summaries by State, as of April 14, 2007.”

- Michael White, “Iraq Coalition Casualty Count,” in iCasualties, accessed on 14 April 2007, at <http://www.icasualties.org.>

- Accredited to Professor Marc Herold of the University of New Hampshire. See <http://www.unknownnews.net/casualties.html.>

- July 2006 figures produced by the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, as cited by David Randall and Emily Goslen, “62,006 – The Number Killed in the War on Terror,” in The Independent, published 10 September 2006.

- Atran, p. 5.

- Kirk Semple, “Chlorine Attack in Iraq Kills 20,” in New York Times, 6 April 2007.

- Atran, p. 43.

- Gunaratna, p. xli.

- Dana Priest, “Jet Is an Open Secret in Terror War,” in Washington Post, 27 December 2004, p. A01.

- Gunaratna, p. 14.

- United States, Department of State, National Security Strategy for the United States of America, The White House (Washington DC: Department of State, September 2002), p. vi.

- Gunaratna, p. 17.

- United States, Department of Defense, Fiscal Year 2008 Global War On Terror Request, The Pentagon (Washington DC: Department of Defense, February 2007), pp. 1-2.

- Ron Scherer, “How US Is Deferring War Costs,” in Christian Science Monitor, 16 January 2007, p.1.

- United States, Department of State, 9/11 Five Years Later: Successes and Challenges, The White House (Washington DC: Department of State, September 2006), pp. 9-13.

- Gunaratna, p. xlvii.

- Osama bin Laden, “Text of Fatwa Urging Jihad Against Americans,” as cited in Christopher Blanchard, CRS Report for Congress: Al Qaeda: Statements and Evolving Ideology, Congressional Research Service, updated 24 January 2007, p. 4.

- President George W Bush, “President Bush Delivers Graduation Speech at West Point,” White House Press Release (Washington, DC: Office of the Press Secretary, 1 June 2002).

- Lieutenant-Colonel Susan L. Gough, “The Evolution of Strategic Influence,” USAWC Strategy Research Project, US Army War College, 7 April 2003.

- “Success in this ideological struggle demands that we explain more effectively our values, ideals, policies, and actions internationally and support moderate voices willing to confront extremists and discredit radicals.” United States, Department of State, 9/11 Five Years Later: Successes and Challenges, p. 21.

- Jessica Stern, Terror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants Kill (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003), p. 296.

- President George W. Bush, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People,” White House Press Release (Washington DC: Office of the Press Secretary, 20 September 2001).

- Osama bin Laden, “Jihad against Jews and Crusaders,” in al-Quds al-Arabi, London, 23 February 1998, p. 3.

- President George W. Bush, “President Discusses War on Terror at National Endowment for Democracy,” Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center (Washington DC: Office of the Press Secretary, 6 October 2005).

- Colin S. Gray, “Maintaining Effective Deterrence,” (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2003), p. 5, as cited in Jeffrey Record, Bounding the Global War on Terrorism (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2003), pp. 2-6.