This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Military History

Canadian War Museum CWM8095

Canadian Gunners in the Mud, Passchendaele 1917, by Alfred Bastien.

Passchendaele – Canada’s Other Vimy Ridge

by Norman S. Leach

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

...I died in Hell (they called it Passchendaele) my wound was slight and I was hobbling back; and then a shell burst slick upon the duckboards; so I fell into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

– Siegfried Sassoon

Introduction

...At last we were under enemy gunfire and I knew now that we had not much further to carry all this weight. We were soaked through with rain and perspiration from the efforts we had been making to get through the clinging mud, so that when we stopped we huddled down in the nearest shell hole and covered ourselves with a groundsheet, hoping for some sort of comfort out of the rain, and partly believed the sheet would also protect us from the rain of shells. I shivered alongside Stephens who was a quiet, kindly and refined lad having his first taste of the front line. Together we huddled in this hole when there was a great thump behind us, but mercifully that shell failed to explode. As the shelling grew worse it was decided we had better move on, so reloading ourselves we pushed through the mud again and amid the din of the bursting shells I called to Stephens, but got no response and just assumed he hadn’t heard me. He was never seen or heard from again. He had not deserted. He had not been captured. One of those shells that fell behind me had burst and Stephens was no more.

– Private John Pritchard Sudbury

Wounded at Passchendaele

26 October 1917.1

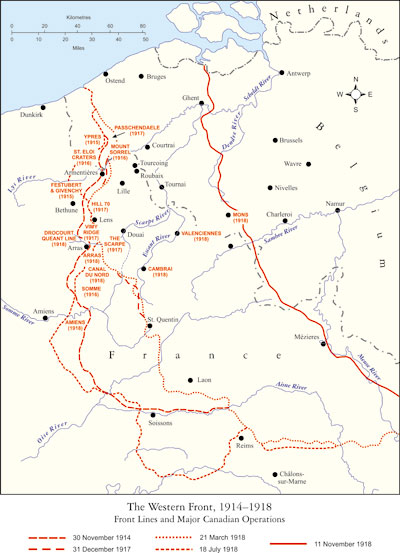

By the spring of 1917, it was clear that the Allies were in trouble on the Western Front. British Admiral Jellicoe had warned the War Cabinet in London that shipping losses caused by German U-Boats were so great that Britain might not be able to continue fighting into 1918. Further, Czarist Russia was teetering on the edge of revolution. If Russia fell, one million additional German troops would be freed to fight on the Western Front. Finally, the recent French offensive on the Chemin des Dames under General Robert Nivelle had lost 200,000 men, resulting in mutinies that threatened the very existence of a French army.

The Allies desperately needed a victory. British Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and French General Philippe Pétain both viewed the war in Europe as a succession of battles that had started with the Somme Offensive in 1916. In attempting to keep pressure upon the Imperial German Army under the command of General Erich Ludendorff, Haig planned for a sweeping breakthrough in Flanders that would result in the Germans being driven back, the submarine bases in Belgium being captured, and the French armies being given a chance to recover their morale.

Haig’s plan pivoted around the Belgian town of Ypres. The only part of Belgium in Allied hands, the Ypres Salient, was open to attack at any time. A ridge, the only high ground in the entire region, ran through Passchendaele, and it was occupied by the German army. With the Germans firmly established upon the high ground, the Allies were vulnerable to constant artillery bombardment.

Haig’s plan was to make a general breakout along the entire front. If the ridge at Passchendaele could be taken and the town itself liberated, the British could turn north and the Belgian coast would be open to them. However, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Haig were both personal and political enemies. Lloyd George did all he could to oppose Haig’s plans in Flanders, suggesting an alternative offensive in Italy. The Prime Minister was convinced that Haig would not be able to break through to Belgium, and Lloyd George would then be left to explain to the citizens of Great Britain why, yet again, their sons were forfeiting their lives to little effect. However, Haig and his supporters eventually won the day, and Lloyd George felt obliged to sanction the plans.

The German Fourth Army – which was holding the line at Ypres – was quick to notice the buildup of Allied troops in the area. Colonel Fritz von Lossberg, Ludendorff’s chief strategist, was sent forward as Chief of Staff to get an accurate assessment of the situation in Flanders. Upon arrival, von Lossberg beheld a marshy, low-lying battlefield that required an elaborate system of dikes and canals to keep the land dry enough to farm. In places, the water table was less than a metre below the surface. Playing to the strengths of the region, von Lossberg deliberately abandoned the German front line positions, preferring to solidify his hold upon the Passchendaele ridge itself. This left a large marshy area in front of the ridge through which the Allied forces would have to fight.

Ludendorff knew that the traditional trench defensive system would be useless once the Allies commenced artillery shelling. He ordered the army to reinforce its trenches with defensive lines of concrete pillboxes designed to withstand the largest British artillery shells. Some of the pillboxes simply would provide shelter for troops to wait out the coming attack and then counterattack, while others housed MG-08 machine guns that would provide enfilading fire. The First Battle of Ypres in 1914 and the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915 had consisted of the Germans attacking the Allies. In 1917, however, it would be the Allies who would be attacking a strongly entrenched enemy – one that was ready and waiting for them.

The Prelude: Messines Ridge

In late May 1917, Allied artillery bombarded the German defences on Messines Ridge, located southeast of Ypres. Then, at 0250 hours on 7 June, the shelling abruptly ceased and the German troops hiding in their reinforced bunkers prepared for the inevitable infantry assault. The Germans then moved reinforcements into place in preparation for counterattacking once the Allies had been turned. However, the British had another plan in mind. For months, engineers had been digging under the ridge, and they ultimately planted 19 enormous mines directly beneath the German positions. The Germans knew the work was taking place, but they were unable to locate the exact location of the excavations. Ultimately, instead of the expected infantry assault, 10,000 German troops were killed when the mines, constituting a total of 450,000 kilograms of explosives, were detonated. Subsequently, the British infantry raced up the ridge to find almost no opposition remaining. The Germans tried to counterattack, but had little luck in doing so. The Battle of Messines Ridge had been a complete success for the Allies, and it was considered a good omen of things to come at Passchendaele.

Haig wanted to press home the attacks, believing that the Germans could be defeated and that he would have his first major success in Flanders. Accordingly, he ordered General Sir Herbert Plumer, the Second Army commander, forward. However, Plumer was not the daring type, and he persuaded Haig to hold off until further preparations could be made. It was a grave error. The Germans were still in disarray and a breakthrough could have had been possible. Plumer’s delay allowed the Germans time to recover, and the opportunity slipped away. However, the battle for Messines Ridge did have one important effect. It convinced Prime Minister Lloyd George that Haig’s plan for a breakthrough might just work, and he was strongly encouraged by the victory.

The Battle of Pilckem Ridge

Haig pushed on with his plans for Flanders. The Third Battle of Ypres was to be led by Sir Hubert Gough and his Fifth Army, with 1 Corps of General Plumer’s Second Army on Gough’s right, and a corps of the French First Army led by General François Anthoine to Fifth Army’s left. All told, 12 divisions were committed to the plan. On 18 July, the British artillery opened fire with over 3000 guns raining down in excess of four million shells upon the German positions. Soldiers of the German Fourth Army had seen it all before, and they knew the British were preparing to attack. Any hope of surprise the British might have had thus evaporated.

At 0350 hours on 31 July 1917, British troops charged forward against the German defences. The Battle of Pilckem Ridge had begun. Stretching across an 18-kilometre front, the attacking troops faced a quagmire. The shelling had destroyed creeks and drainage canals just as the worst rains in 30 years started to fall. Allied soldiers struggled arduously through the clinging mud. Machine guns in von Lossberg’s pillboxes fired incessantly on anyone who dared move in No Man’s Land. Ultimately, the Allies were able to make only small gains on the left of the ridge, and the French were held in check to the north. For a mere 2000 yards of ground gained, the allies suffered 32,000 casualties. While the cost of taking Pilckem Ridge had been high, after the war, General Ludendorff would report that it had cost the Germans dearly as well: “...besides the loss of from two to four kilometres along the whole front, it caused us very heavy losses in prisoners and stores, and a heavy expenditure of reserves.”2

The Battle of Langemarck

Haig was now even more convinced that success was within his reach, and he ordered the continual shelling of German positions throughout early August 1917. When the shelling was combined with the torrential rains, the battlefield became a sea of mud pockmarked by millions of shell holes. Broken trees littered the landscape, and each shell churned the ground, exposing bodies of men lost in earlier battle. Weighed down with over 24 kilograms of personal equipment, men who slipped off the wooden duckboards often drowned. Their comrades were ordered not to even attempt a rescue, as a drowning man often pulled his rescuers down with him.

By 16 August, conditions had finally improved enough for the British to continue the attack. Four days of fighting at the Battle of Langemarck saw few gains, but this combat action cost the British heavy casualties. Haig, frustrated by the lack of success, replaced Sir Hubert Gough with General Plumer. Plumer then prepared a plan which concentrated on small gains rather than pushing for one large breakthrough.

Nonetheless, the Germans were also suffering. According to Ludendorff: “The costly August battles imposed a heavy strain on the Western troops. In spite of all the concrete protection they seemed more or less powerless under the enormous weight of the enemy’s artillery. At some points they no longer displayed that firmness which I, in common with the local commanders, had hoped for.”3

The Battle of Menin Road

As it unfolded, Ludendorff did not see any improvement in September:

After a period of profound quiet in the West, which led some to hope that the battle of Flanders was over, another terrific assault was made on our lines on the 10th of September. The third bloody act of the battle had begun. The main force of the attack was directed against the Passchendaele-Gheluvelt line.

The enemy’s onslaught on the 10th was successful, which proved the superiority of the attack over the defence. The power of the attack lay in the artillery, and in the fact that ours did not do enough damage to the hostile infantry as they were assembling, and, above all, at the actual time of the assault.4

The British now had 1295 artillery pieces in place, one for every five yards of the attack front, to fire upon the German positions. And on 20 September 1917, the Battle of Menin Road commenced. Ludendorff later stated: “Obviously the English were trying to gain the high ground between Ypres and the Roulers-Menin line, which affords an extensive view in both directions. These heights were also exceptionally important for us, as they afforded us ground observation posts and a certain amount of cover from hostile view.”5 As it materialized, the British suffered 21,000 casualties in the face of a now semi- permanent German front line that was supported by artillery ranged in upon No Man’s Land. Subsequently, wave upon wave of German counterattacks crashed upon the British positions, but those Allied troops held the 1500 yards they had captured initially.

According to Ludendorff, the British attacks were taking a toll: “Another English attack on the 21st was repulsed but the 26th proved a day of heavy fighting, accompanied by every circumstance that could cause us loss. We might be able to stand the loss of ground, but the reduction of our fighting strength was again all the heavier.”6 The British continued toward the southwestern edge of the salient in an action that would become known as the Battle of Polygon Wood. During the period from 26 September to 3 October, British troops gained an additional 2000 yards of ground in advancing upon both Polygon Wood and Broodseinde. At a cost of an additional 30,000 casualties incurred, the British found themselves directly under Passchendaele Ridge – and German artillery fire. It was now imperative that the ridge be captured quickly.

The Battle of Broodseinde

It was not just the Allies who were suffering. “Once more we were involved in a terrific struggle in the West. October came and with it one of the hardest months of the war. I had not known what joy meant for many a long day,” Ludendorff wrote.7 And lessons were being learned. On 4 October, after two solid months of fighting, the Australians managed to capture Passchendaele Ridge at the Battle of Broodseinde. Ahead of them lay the town of Passchendaele itself. Ludendorff would write after the war, “...that the actions of the Third Battle of Flanders had presented the same set-piece characteristics. The depth of penetration was limited so as to secure immunity from our counter-attacks, and the latter were then broken up by the massed fire of the Artillery. As regards the battle on the 4th of October, again we only came through it with enormous loss.”8

As it happened, Broodseinde proved to be the high point for the Allies in Flanders in early October. On 9 October, their forces were ordered to take the town of Poelkapelle. This battle was a total failure. The troops were exhausted, the mud was proving to be as great an adversary as the Germans, and morale was at an all-time low. Any advances made were soon lost to German counterattacks. By 12 October, the Allies had suffered an additional 13,000 casualties, and the attacks were called off.

National Archives PA-002084

The Canadians

Haig knew that the 100,000 casualties the Allies had suffered in this campaign would be wasted if Passchendaele itself was not captured. He took some solace from the fact that the high ground above Ypres was now in Allied hands, and that if they could push past Passchendaele, the way to the Belgian coast would be open. Haig decided that the British, Australian, and New Zealand troops upon whom he had relied so far could do no more. Thus, he turned to the Canadians. He knew that the troops of the Canadian Corps had well earned their reputation as an elite force ready to take on the toughest jobs. With successes at Vimy Ridge and the Battle of Hill 70 behind them, Haig ordered two divisions of the corps to Passchendaele.

Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, the former Victoria businessman and militia officer who had succeeded General Sir Julian Byng as commander of the Canadian Corps, strongly objected. He felt that his men had not yet recovered enough for a new, pivotal battle. However, the British High Command insisted that Passchendaele was worth the effort, and Haig personally convinced Currie to accept the tasking. That said, Currie did wring a number of concessions out of Haig. Knowing that advance preparation, best exemplified by the plans that had been scrupulously laid down for the attack at Vimy, had led to the recent successes of the Canadian Corps, Currie insisted that there would be no attack on Passchendaele until he personally felt the men were ready. He also demanded that the Canadians be allowed to leave the salient once the battle was over. Sir Arthur was determined that Canadian lives would not be spent in both attacking and then subsequently defending Passchendaele.

Preparations

You will not be called upon to advance until everything has been done that can be done to clear the way for you. After that it is up to you.

– Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie to his infantry9

The Ypres Salient was in utter disarray. William John McLellan, who was a student at the University of Alberta when he enlisted in 1916, described the Passchendaele battlefield as “...simply miles and miles of shell holes – all filled with water and the whole ground so water-logged that you go down over your knees every step and you have to keep moving or I guess you would go out of sight. To say its muddy is putting it mild. (sic) By a long ways. Besides that it rains practically every day & every hour. You get wet and stay wet all the time your (sic) in the forward area...”10

And it was not just the mud. The Canadians still faced the reinforced concrete pillboxes. As Major Robert Massie of the Canadian Artillery wrote: “These pill-boxes vary in size, some being 8 by 10 feet inside, some bigger. There would be 12 to 18 inches or 2 feet of concrete on the sides which are exposed to our shell fire, and from 2 to 5 inches on the top, the whole reinforced with steel work. It is a small target for a heavy gun to hit. An 18-pounder shell or a 4” or 5” Howitzer shell just bounces off it, on account of the construction of the shell and the solidity of the object which it hits. I would be very doubtful whether the 6 inch guns would smash up the pill-box or not.”11

Currie personally inspected the battlefield and predicted that the Canadians would be successful, but that it would cost 16,000 casualties. He also demanded that if the Canadians were to fight at all, it would be with Plumer’s Second Army, and not with Gough, whom he personally did not like and also distrusted. Currie then ordered his officers to prepare to take Passchendaele.

Robert Massie later reported his impressions of his first visit to the battlefield. “The first day I went in, the mud was 6 inches deep everywhere, and in most places half way up to my knees. It would dry up sometimes, but would always rain afterwards and be worse than ever. The surrounding country was literally shot to pieces, looking like a field after trees and stumps have been pulled out, except that the holes are as deep as 10 feet and filled with water. The lips of one shell hole practically touch the lips of another, so that horses and mules could not go across the area. The first lot would get across, but half a dozen following would soon turn the whole thing into a mass of water and mud so that the animals could not make it at all.”12

General Currie knew that if the Canadians were to be successful at all, men, munitions, and equipment would all have to be moved to the front line quickly and efficiently. Therefore, the first tasks were to rebuild the decimated transport system and to drain the swamps around the town. Major-General (later Sir David) Watson, the 4th Division commander, later wrote as he watched the preparations:

Our engineers at once started to lay our French Railways, guns were brought well forward, dumps of ammunition and supplies established, dressing stations located, and proper jumping off positions for the infantry were dug and prepared. Night and day the work progressed under most trying and difficult situations...13

Other individuals voiced other trepidations. Robert Massie was concerned with respect to the safety of the guns. “The infantry also had to go forward, and their advance was assisted by constructing duck-walks, that is, the short duck boards that are put in the trenches to form a footing for the infantry; they put them two boards wide for several miles out to form paths for the infantry; but the artillery was obliged to stick to the roads.”14 And effective communications had become an obsession for Currie and his staff. They found that telephone wires that were normally buried three feet down were being blown up as German artillery shells ploughed into the soft earth. Currie therefore ordered the wires be buried to a depth of six feet. Where laying wires was impossible, runners hand-delivered messages to and from the front lines. Units were even issued carrier pigeons in case the runners could not get through.

Artillery barrages were to be used to cut the barbed wire that protected German defences, with artillery observers using wireless sets to call in attack coordinates. At Vimy, the Canadian staff had surprised all and sundry by giving each individual soldier a map so that they knew exactly what their specific objectives were, and when they were supposed to be there. Currie would continue this practice at Passchendaele. To further assist the infantry, and mirroring the preparations made for the Vimy attack, the engineers built replica German pillboxes and trenches so the Canadians could practise the upcoming assault over and over again.

Everyone located in the forward areas was under constant enemy observation and bombardment. Even as pioneer units built new roads and bridges for the infantry, German tactical bomber aircraft dropped explosives upon these men and their handiwork. Altogether, 1500 Canadians would be killed in the preparatory phase alone for the battle.

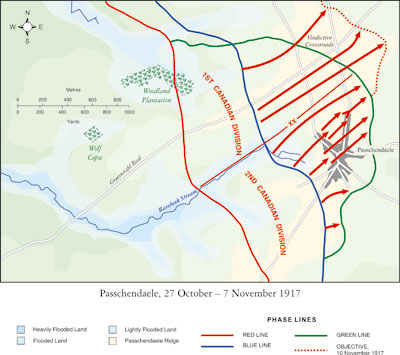

The Plan

A few days prior to the attack on Passchendaele, General Watson heard Haig say: “The Canadian Corps would be the determining factor, for the date of the operation, as ours was the big effort, all the others being subsidiary to our main operation of the capture of Bellevue Spur, Crest Farm, and Passchendaele itself.”15 Sir Arthur Currie had laid out a simple and straightforward plan to take Passchendaele. The Canadians would attack in a series of coordinated operations, each with a limited objective, until the village itself and a defensible position upon the Passchendaele ridge had been gained. The overall goal was to drive a thin wedge into the German positions.

Currie’s initial goal became identified as the Red Line on Canadian maps, the first of several coloured lines used to mark battle objectives. The Canadians would attack in two columns around the Ravebeek Swamp. If they were to make their goal of advancing 1200 metres to Friesland on the edge of the swamp, 3rd Division would have to overcome a series of pillboxes at Bellevue Spur. The principal objective for the 4th Division was Decline Wood and the Ypres-Roulers Railway line, which lay only 600 metres away.

In a preparatory bombardment, conducted between 21 October and 25 October, 587 field guns shelled German positions. Rolling barrages moved across No Man’s Land – temporarily stopping but then only to start once again. The Germans, crouching in their pillboxes and dugouts, could not tell when the actual assault was to begin. Unlike what had occurred in the past, this time, the element of surprise would be on the side of the Canadians.

Even as the tensions mounted, the Canadian officers and men were ready. Robert Massie spoke for many of the Canadians: “Passchendaele probably appealed to all of us more than any other action this year on account of the difficulties that existed in connection with it, and because of the fact that other troops had failed to take it.”16

National Archives PA-002162

The Battle of Passchendaele

At precisely 0540 hours on 26 October 1917, Canadian heavy machine guns opened fire. Two minutes later, every gun in the Canadian batteries was simultaneously firing. Press reports later revealed that the opening barrage could be heard in London. And the rolling barrage made its first trip across No Man’s Land. Mortars bombarded pillboxes, and barbed wire was blown out of the way. The barrage was not like those at Vimy, where a single curtain of shells had fallen onto the battlefield. At Passchendaele, seven distinct lines of bombardment were utilized. In all 20,000 Canadian foot soldiers crawled out of dugouts and trenches, advancing under a mist that quickly turned to rain. The rolling barrage provided some protection, but it moved so quickly and was so complex that it permitted German gunners to target the advancing Canadians. Robert Massie later recalled:

...The 3rd and 4th Divisions had to attack over low ground, called marsh bottom on the maps, prior to reaching the higher ground on the other side which was named Bellevue Heights, on which there were a number of pill-boxes. It rained that night, so that in the morning the going was extremely difficult. The barrage opened fairly well on time, and after the light got stronger, about half past eight or nine o’clock, I could see the infantry going forward fairly well up with the barrage, but the going was so difficult that the men could not keep pace with the lifts of the barrage-I think it was 50 yards every four minutes; ordinarily, on dry ground, we had 100 yards every two or three minutes.17

Massie then continued: “I could see the barrage on our left going further ahead of those men, and it was quite impossible for them to keep up. You could hardly distinguish them; if they had not been moving you could not tell them from the ground. I don’t believe they had been going ten minutes before they were all soaked and covered with mud, head to foot.”18 The 3rd Division crept ahead crater to crater. They quickly found that mortars and rifle grenades could be used, with great effect, against the pillboxes on the Bellevue Spur. Lewis gun teams were called up when the fighting was particularly heavy, and soon, the Canadians were established upon the Red Line east and north of Passchendaele itself.

The 4th Division made it even farther. Being required to advance a shorter distance, they actually pushed through to the next objective temporarily – the Blue Line. However, the Germans responded on 27 October with heavy counterattacks that ultimately drove the Canadians out of the newly captured Decline Wood. Then, during the night of 27-28 October, the Canadians retook Decline Wood after intense hand-to-hand combat, often conducted at the point of bayonets. The 3rd Division had also run into trouble advancing north of the Ravebeek Swamp. Intense enemy artillery bombardments caused a temporary retreat to their original positions until reserves came up to assist in the advance. Over the next two days, the Canadians dug in to hold onto their gains. Seven battalions, each with an average battle strength of 600 men, lost a total of 2481 men in combat. Private Richard Mercer summed up the fighting as follows: “Passchendaele was just a terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible place. We used to walk along these wooden duckboards – something like ladders laid on the ground. The Germans would concentrate on these things. If a man was hit and wounded and fell off he could easily drown in the mud and never be seen again. You just did not want [to] go off the duckboards.”19

It was no easier on the enemy. Ludendorff would later claim: “The horror of the shell-hole area of Verdun was surpassed. It was no longer life at all. It was mere unspeakable suffering. And through this world of mud the attackers dragged themselves, slowly, but steadily, and in dense masses. Caught in the advanced zone by our hail of fire they often collapsed, and the lonely man in the shell-hole breathed again. Then the mass came on again. Rifle and machine-gun jammed with the mud. Man fought against man, and only too often the mass was successful.”20

|

|

National Archives PA-002367

On 30 October, the Canadians turned their attention back toward the full Blue Line objectives. “...the actual final assault on Passchendaele [will be] strongly defended at Meetcheele on the Bellevue Spur. At the Vapour Farm House, the 1st Division is to join hands with the 2nd British Army Corps in order to push forward northeast, while the 2nd Division takes over for the assault on the town.”21

This time, the preliminary artillery bombardment would commence at 0550 hours, with 420 guns firing for effect. The gunners purposely aimed for the pillboxes, but this time they did not attempt to score direct hits. It had been determined that if shells landed just in front of the pillboxes, they could be knocked off their foundations. Attacking infantry would then mop up the enemy as they scrambled from the ruined structures.

Currie’s strategy of taking and then holding small gains was working. Together with two British divisions, the Canadians moved toward the village of Passchendaele. Under the cover of a driving rainstorm, they quickly reached the outskirts of the now-ruined municipality. For five days, often immersed up to their waists in mud and under intense German artillery fire, these troops held on, waiting for relief. And by the time the 1st and 2nd Divisions relieved these embattled troops, 80 percent of the 3rd and 4th Divisions had become casualties.

National Archives PA-002058

Canadian soldiers with German POWs after the battle.

Passchendaele – At Last

By 6 November, the Canadians were prepared to advance upon the Green Line. The final objective was to capture the high ground north of the town and to secure positions on the eastern side of Passchendaele Ridge. Again, according to Major Robert Massie: “The third attack ... was the day when the First and Second Divisions took Passchendaele itself. On this occasion, the attack went off the most smoothly of any of the three. They had fair ground to go over, and especially those that went into Passchendaele itself had pretty fair going, and the objectives were reached on time.”22

After early hand-to-hand fighting, the 2nd Division easily occupied Passchendaele just three hours after commencement of the attack at 0600 hours. The 1st Division, however, found itself in some trouble when one company of the 3rd Battalion became cut off and was stranded in a bog. When this situation eventually righted itself, the 1st Division continued toward its objectives. Well-camouflaged tunnels at Moseelmarkt provided an opportunity for the enemy to counterattack, but they were fended off by the Canadians. By the end of the day, the Canadian Corps was firmly in control of both Passchendaele and the ridge.

The final Canadian action at Passchendaele commenced at 0605 hours on 10 November 1917. Sir Arthur Currie used the opportunity to make adjustments to the line, strengthening his defensive positions. Robert Massie summed up the thoughts of many participating Canadians as follows: “What those men did at Passchendaele was beyond praise. There was no protection in that land. They could not get into the trenches which were full of mud, and you would see two or three of them huddled together during the night, lying on ground that was pure mud, without protection of any kind, and then going forward the next morning and cleaning up their job.”23

We were given the almost impossible to do, and did it.

– Lieutenant-Colonel Agar Adamson24

Conclusion

The Canadians had done the impossible. After just 14 days of combat, they had driven the German army out of Passchendaele and off the ridge. There was almost nothing left of the village to hold. Altogether, the Canadian Corps had fired a total of 1,453,056 shells, containing 40,908 tons of high explosive. Aerial photography verified approximately one million shell holes in a one square mile area. The human cost was even greater. Casualties on the British side totalled over 310,000, including approximately 36,500 Australians and 3596 New Zealanders. German casualties totalled 260,000 troops.

For the Canadians, Currie’s words were prophetic. He had told Haig it would cost Canada 16,000 casualties to take Passchendaele – and, in truth, the final total was 15,654, many of whom were killed. One thousand Canadian bodies were never recovered, trapped forever in the mud of Flanders. Nine Canadians won the Victoria Cross during the battles for Passchendaele. While the human cost had been terrible: “Nevertheless, the competence, confidence, and maturity began in 1915 at Ypres a short distance away, and at Vimy Ridge earlier that spring, again confirmed the reputation of the Canadian Corps as the finest fighting formation on the Western Front.” So wrote esteemed Professor of History Doctor Ronald Haycock at the Royal Military College of Canada for The Oxford Companion to Canadian History in 2004.

Haig proved to be true to his word. By 14 November 1917, the Canadians had been returned to the relative quiet of the Vimy sector. They had not been asked to hold what it had cost them so much to take. However, by March 1918, all the gains made by Canada at Passchendaele would be lost in the German spring offensive known as Operation Michael.

General Sir David Watson praised the Canadian effort: “It need hardly be a matter of surprise that the Canadians by this time had the reputation of being the best shock troops in the Allied Armies. They had been pitted against the select guards and shock troops of Germany and the Canadian superiority was proven beyond question. They had the physique, the stamina, the initiative, the confidence between officers and men (so frequently of equal standing in civilian life) and happened to have the opportunity.”25

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was even clearer when it came to the Canadians: “Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line they prepared for the worst.”26

![]()

Calgary historian Norman Leach was engaged to ensure the historical accuracy of Passchendaele, the feature length film produced and directed by Paul Gross. Leach is a graduate of the University of Manitoba and has written four books on Canadian Military history, the latest being Passchendaele: Canada’s Triumph and Tragedy on the Fields of Flanders.

Notes

- <www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/canada-europa/brussels/passchendaele/letters-en.asp>

- <www.firstworldwar.com/source/ypres3_ludendorff.htm>

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- <www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/canada-europa/brussels/passchendaele/battle-en.asp>

- Ibid.

- The Empire Club of Canada Speeches 1917-1918. Toronto: The Empire Club of Canada pp. 86-96, Speaker: Robert Massie, Officer, Canadian Artillery, 17 January 1918.

- Ibid.

- Records of the Great War, Vol. V, Charles F. Horne (ed.), National Alumni 1923

- Massie speech, 17 January 1918.

- Horne

- Massie speech, 17 January 1918.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- <www.scottish.parliament.uk/business/officialReports/meetingsParliament/or-07/sor0131-02.htm>

- <www.firstworldwar.com/source/ypres3_ludendorff.htm>

- <www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/canada-europa/brussels/passchendaele/battle-en.asp>

- Massie speech, 17 January 1918

- Ibid.

- <www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/canada-europa/brussels/passchendaele/battle-en.asp>

- Horne

- <www.vac-acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=history/firstwar/canada/Canada8>