This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Military History

Canada. Patent and Copyright Office/Library and Archives Canada/PA-030096

Bird’s eye view of McGill College, 1914.

McGill’s Contingent of the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps (COTC) 1912-1968

by Desmond Morton

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Montréal’s McGill University led its Canadian counterparts when it organized its version of a college-based Officer Training Corps (OTC) in September 1912. The innovation came, of course, from the usual source for Canadian military innovations: Great Britain. The COTC would play a significant role in the university, contributing thousands of McGill undergraduates, male and female, to two world wars and to Canada's Cold War defenders. During its post-1945 years, McGill's COTC helped create hundreds of student summer jobs that, for a frugal student, covered tuition and living costs for the ensuing academic year. Like other institutions, the McGill COTC died – a victim of a federal government’s reduced priority for defence, and the sweeping reconsideration of reserve officer provision in the newly-unified Canadian Forces. Despite its role in financing students, in the radical mood of the late 1960s McGill's COTC died virtually unmourned, save by a few who had given it their best years, and others who remembered both comradeship and a patriotic sense of self-sacrifice. Even remembrance of the University's war dead perished until the students themselves revived Remembrance Day at McGill during the 1990s.1

Background

Once Canada had contributed several thousand men to Great Britain's war with the two Boer republics in South Africa, its future as a dutiful auxiliary in Britain's war was virtually determined.2 At the 1908 Imperial Conference, Canada formally committed itself to adopting British tactics, organization, arms, and equipment to guarantee the fullest possible integration of its forces with those of the British Empire. In a brief but significant burst of militarism, influential, wealthy and conservative opinion leaders from across the country formed the Canadian Defence League (CDL) in 1909 to urge citizens to adopt universal military training. As a preliminary, Laurier Liberals persuaded every province but Saskatchewan to compel boys in high school to participate in compulsory cadet training. As Member of Parliament (MP) for King's County in Nova Scotia, Laurier's defence minister, Sir Frederick Borden, persuaded a sympathetic provincial government to compel would-be school teachers, male and female, to qualify in drill and physical training (PT). Male teachers were also required to qualify in marksmanship.

Such policies obviously claimed bipartisan and public approval.3 The Conservatives' military critic, Colonel Sam Hughes, was an outspoken supporter of universal military training although he believed that the combination of training and patriotism would easily suffice to mobilize volunteers in the event of war. Colonel Hughes's brother,James Laughlin Hughes, was Toronto’s inspector of schools. There, his feminist principles had supported equal pay for female and male teachers as well as extending the curriculum to include music and art. The privilege of drill and cadet training would be extended to all high school students, male and female. Such training, the Hughes brothers argued, improved both physique and awareness of the social order. "Boys," James Hughes advised teachers, "…should be trained to make a proper soldier-salute in passing any gentleman to whom a mark of respect is due. In passing a lady," he explained, "the salute should be given in a somewhat slower manner, and the hat should be raised slightly."4

Nor was cadet training rejected by French Canada. From the late 1870s, Quebec's Catholic colleges collected federal subsidies for cadet training. Using Ottawa's money to finance the cheapest imaginable physical training – military drill – troubled no constitutional consciences. If drill inculcated discipline and due subordination, tant mieux! One of Henri Bourassa's chief allies in fostering Canadien nationalism, Captain Armand Lavergne, assured Toronto's Canadian Military Institute that Quebec was staunchly behind juvenile military training. "There is no doubt that compulsory cadet service in the schools or educational houses of our country is most beneficial, as it teaches the young men the lesson of patriotism and citizenship and teaches them to have a sound mind in a sound body."5

War Clouds Looming

McGill's 1912 adventure in military training for its students was no mere ‘knock off’ from Canada's high schools; it was consciously imperial. During the Boer War, an acute shortage of suitable officers had persuaded the British army to look to universities as a source of young men of appropriate breeding and intelligence.6 Officer training corps (OTCs) spread through institutions of higher learning in the 1900s as Britain, guided by Richard Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, began preparing Britain's army for what he anticipated as an approaching European war. British tradition had accepted a small voluntary regular army, officered by sons of the landed aristocracy and the professions. Expansion to the size needed for a European war led Haldane to merge the historic county militia and the Victorian era urban-based volunteers into a potentially huge Territorial Army. OTCs promised partially-trained officers for a partially-trained army. Enrolment was voluntary, and Haldane's Liberal principles ensured that OTC membership implied no compulsion to serve. Like Hughes, Haldane was confident that patriotism would suffice when the moment of decision came.

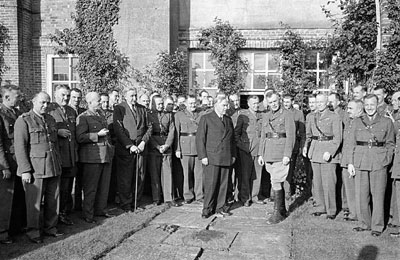

© Bettmann Collection/Corbis/U172299INP

Auckland Geddes aboard the SS Mauretania, 1922.

Few had been as keen on the OTC movement as a 1912 appointment to McGill's Faculty of Medicine. Dr. Auckland Geddes was a distinguished anatomist, born into a wealthy and prominent family. Despite Geddes’s feeble eyesight, the army had reluctantly accepted him as an infantry officer in the Boer War, although it refused him a regular army commission on the same grounds. Appointed to an Edinburgh hospital after he was demobilized, Geddes promptly formed a Territorial Army medical unit in Scotland, and another, later, in Dublin, after he moved to the main medical school located there. In 1912, he came to McGill to please his Nova Scotia-born wife, and to fill the university’s chair in anatomy.7 Geddes found a congenial audience for his views, and soon became an apostle for the doctrine of universal military training in Canada, a goal already embraced by the CDL. McGill's Principal, William Peterson, was an ardent imperialist, as was the economist and humorist, Stephen Leacock. His dean, Herbert S. Birkett, was an officer in the Militia's medical corps, and McGill's medical historian, Sir Andrew Macphail, was an uncompromising enthusiast for military training for the young. Militarism, he insisted, was part of the spirit of the age. "The school mistress, with her book and spectacles, has had her day in the training of boys; and sensible parents are longing for the drill sergeant carrying in his hand a good cleaning rod or a leather belt with a steel buckle at the end. That is the sovereign remedy for the hooliganism of the town and the loutishness of the country.”8

The CDL and imperial triumphalism inspired Canada's closest brush with militarism. The spread of compulsory cadet training across Canada, backed by a significant campaign for military training for all Canadians, was echoed in Australia, where a similar movement was more successful. The League's version of militarism depended upon a tide of nativism reacting against the Liberal policy of mass European immigration to populate the West. Also, the presence of conscription in most European countries presented a threat to what Geddes, CDL leaders, and probably a majority of Canadians considered as their ‘mother country,’ Great Britain.9 If young men could be compelled to train, Canada must imitate Britain by finding and training military officers and instructors within Canada's growing university system.

A key component of Canada's cadet movement was provided by a philanthropist already well-known to McGill University. Canada's High Commissioner in London, Donald Smith, (Lord Strathcona) had built a fortune from investments in the Canadian Pacific Railway and through the Hudson's Bay Company. He chose the 1909 Imperial Conference to announce a gift of a quarter-million dollars in prizes to encourage physical and military training in Canada. His money was reserved for public schools, but, true to the principles that led him to pave the way for women to study at McGill, he made his awards available to girls as well as boys. In October, 1910, Strathcona doubled his contribution to $500,000. In all provinces but Saskatchewan, agreements were signed with Ministers of Education or, in Quebec, with the Catholic and Protestant school commissions. 10 Robert Borden’s defeat of Sir Wilfrid Laurier's Liberals in 1911 led to the selection of ultimate militarist Colonel Sam Hughes to the Militia Department, and gave the CDL hopes of early success. As minister, Hughes's first priority was a campaign to drive liquor out of "wet canteens" in militia camps, and from officers' messes. His reasons were consciously directed at those concerned with ‘up-building’ the young of Canada. No longer would physical fitness and the healthy military life under canvas be contaminated by booze and boozers.11

Passionately imperialist in ideology, McGill reflected the militarism of its age. In his official history of the university, Stanley Frost reminds us that McGill had provided students with a rifle range as early as 1903. By 1907, the university offered courses in military engineering, taught by British army officers to students in the applied sciences. As with British-based OTCs, such courses led to British and Canadian officers' commissions. In 1912, Captain Charles McKergow, one of McGill’s engineering instructors, was contacted by a Montréal militia staff officer to organize an OTC for McGill students. Principal Peterson warmly approved, and promptly chaired a meeting where 125 young men promised to join if an organization got the go-ahead. After a mass meeting – with speeches from Colonel Crowe, commandant of the Royal Military College at Kingston, and local militia staff officers – 50 undergraduates signed up.12 The Militia Department issued khaki caps, jackets, overcoats, and puttees, and corduroy breeches as well as a Mark II Ross rifle, a bayonet and belt. In the autumn of 1912, McGill's OTC took shape under Captain V.I. Smart of the 5th Royal Highlanders, who taught military engineering at McGill, with two companies, each consisting of 59 all ranks, and they held regular classes and drill sessions. The Joseph House, on the site of McGill's present McLennan Library, became the armoury. Colonel Jeffrey Burland of the Victoria Rifles agreed to become Honourary Colonel, and McGill's Chancellor, Lord Strathcona, donated $100,000 to equip the new COTC headquarters for its military role.13

McGill University's venture in officer training was proudly British in inspiration and affiliation. Young men who enrolled in the new McGill OTC were promised British army commissions as second lieutenants after three years of training, and a full lieutenancy after a fourth year. Ottawa approved a Canadian Officers' Training Corps (COTC), and allowed McGill to claim the first contingent. Laval University, whose students had long officered the local 9th Voltigeurs, followed. Although it had become the home and heart of the Canadian Defence League, Toronto's university begged off the COTC after its managers reckoned the costs. Principal Maurice Hutton of University College, who had proclaimed that it was impossible to have too much militarism but dangerously easy to have too little, had to explain to the press that University of Toronto students did not really have enough time to spare for military training.14 By 1912, Canada was descending into an acute recession. Not even the promise of $500,000 from the Leonard family could persuade Queen's University's managers to get involved. By the spring of 1914, the CDL had collapsed under its perennial factionalism and lack of funds. Paradoxically, Canada's moment of militarism passed only a few months before the Great War began.

The Great War

McGill's COTC almost shared its fate. After the Great War began, the War Office cancelled its OTC programs. Its staff officers and instructors were needed for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Across the Atlantic, McGill's contingent was also left in limbo. A surplus of militia officers overflowed the mobilization camp at Valcartier. As the Minister, Sam Hughes, and his acolytes struggled to organize a division-sized contingent of 20,000 out of 35,000 volunteers, officer shortages were hard to foresee. That changed only in 1915-1916, after Sir Robert Borden committed Canada to create an overseas army of a quarter million, and then half a million soldiers out of a peacetime militia of under 60,000 all ranks, and a total population of barely eight million people.

Brown, Horace/Library and Archives Canada/PA-107281

Sam Hughes at the embryonic Camp Valcartier, 13 September 1914.

In 1913, a patriotic donor had sent the McGill battalion 500 pairs of snowshoes. Although McGill's COTC would boast of being the first OTC to manoeuvre in snow, the winter of 1914 saw virtually no snow in Montréal. However, the new Montréal High School, across University Avenue from McGill, built a rifle range that the University's COTC contingent could use. Henry Morgan's department store offered a warehouse on Beaver Hall Hill for the same purpose.15 No longer certain that OTC training would gain them a commission, McGill's cadets drilled, recruited hundreds of fellow students, fired their rifles, and read the war news.

A belated concern for defending Canada itself, perhaps from Germans or even Fenians lurking in the neighbouring republic, inspired an unofficial home guard movement in Montréal and Toronto, based upon unspecified obligations. Some adventurous women decided that it was their duty to learn to shoot. McGill's male undergraduates were easily inspired, or bullied, or shamed into becoming early 20th Century warriors – learning how to ‘slope arms’ or ‘form fours’ in the ranks of the COTC. William Peterson, McGill's principal, was in England when the war began, but leading members of McGill's alumni association, the Graduates' Society – J.C. Kemp. Paul F. Sise, Allan Magee, George McDonald, Gregor Barclay, and Percival Molson – took the initiative by organizing a McGill Provisional Battalion from students, graduates, professors, and even citizens with no university connection. Major Auckland Geddes eagerly accepted the command, until mid-October, when he was summoned to England to become an infantry officer.16> His successor in the McGill battalion was Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Starke of Montréal’s Victoria Rifles. Starke soon made way for Allan A. Magee, an Ontario-trained lawyer and company director, and one of the OTC's original officers.

Geddes had imposed an appropriate rigour upon McGill battalion training. Attendance at drill was made compulsory. Saturdays included a hike over Mount Royal, marching ‘on the double’ through Westmount, and compulsory attendance at drill sessions during the week. The new regime soon eliminated portly old professors and aging business magnates eager to appear patriotic. Exhausted elders were assured that they could better do their duty by applauding from the sidewalks. Only personal illness or family bereavement was an acceptable excuse for skipping drill, and, as if the students had skipped a class, the penalty included a personal appearance before their dean. Frank Adams, the Dean of Practical Science (or engineering), and the Dean of Arts, Professor Walton, were privates in the McGill regiment. On 1 October 1914, the governor general, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, reviewed the unit and urged its organizers to train officers for whatever engineering and medical units, "the Empire's War Lord," Lord Kitchener, might demand. Summoned home to England to perform his military obligations as a ‘Territorial,’ Geddes passed his command to Lieutenant-Colonel Allan A. Magee. After a November visit, the Minister of Militia, now Sir Sam Hughes, attempted to clarify the status of the McGill unit, declaring that the McGill battalion was now a thousand-member, eight-company unit of the COTC. Those who wished to qualify for Canadian commissions were given a deadline to declare their intentions.17

Soon thereafter, the contingent claimed its first casualty. Football player John Abbott, a lieutenant in the OTC, died after a sports accident had been aggravated by acute blood poisoning, attributed to his devotion to military training. A firing party accompanied his interment at Montréal’s Protestant Cemetery.

Whatever its reputation in later years as an organ of radical pacifism, McGill's student-run newspaper, The Daily, was a fervent supporter of the wartime COTC, denouncing "slackers," who failed to enlist, or who skipped drill. McGill, it insisted, had a role in the world. On 3 November 1914, The Daily complained that although 925 men had enrolled in the McGill battalion, its largest parade had assembled a mere 412, "…a poor showing and disheartening to those who are devoting their time to the training of the men."18 A bigger issue was whether the McGill soldiers would ever fight and die. "Is our university to stand idly by," it demanded, "while the future of all her ideas of liberty and progress is determined by the sword? Can she not strike for freedom? Is she important? Does a year, a place, a class, does the future of anyone matter, when all we have and are is at stake?" (The Daily, 1 October 1914) Although Sam Hughes had cautiously reminded onlookers that the COTC itself could not go to war, TheDaily demanded, "… [a] McGill unit of some sort to take its place in the battle line."19

Orpen, William, Sir/Sir William Orpen Collection/Library and Archives Canada/accession no. 1991-76-1

Sir Robert Borden.

One answer was to raise a company under Captain Gregor Barclay to form part of Ottawa's 38th Battalion, then in the process of formation under a McGill graduate, Lieutenant-Colonel C.M. Edwards. Volunteers were scarce, as The Daily, for all its patriotic fervour, warned that joining the 38th would end a student's university career with a private's pay and trash his social status.20 A better solution soon suggested itself. British army reservists living in Canada when war broke out had been spared the duty of reporting to their old units if they joined a special unit of the CEF known as the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), named after the governor general's daughter. Given the competing pay scales – a shilling a day for a British private, four times as much ($1.10 a day) for a Canadian – a thousand trained British reservists were easily persuaded to enlist. By December 1914, the PPCLI was in the trenches. By the time Canadians had lost 6000 men to German gas and artillery at Ypres in April 1915, the Patricia's had also suffered formidable losses. What else could an elite unit expect? How could its ranks be filled? University students, already members of a social elite, provided opportune replacements. Members of the COTC across Canada were recruited into university companies, and despatched to fill the ranks of the Patricia's. The second of five such companies came mainly from McGill, as did its commander, Captain Percival Molson. Molson's prestige and that of the Patricia's seems to have overcome the resistance to fighting the war as a private soldier.21 The company joined the Patricias shortly before its epic defensive battle at Hooge in June 1916, and the losses among the Montréalers were heavy.22

Like other universities, McGill's medical faculty organized medical units, among them No. 3 Canadian General Hospital. The Royal Victoria Hospital, a McGill affiliate, recruited most of the nursing sisters. No. 3 General Hospital also attracted the poetic Boer War veteran, Professor John McCrae, previously serving as a unit medical officer.

Sending university students to fill the ranks of the PPCLI was as much a waste of trained manpower as was the PPCLI itself. The raw battalions of the First Contingent badly needed both trained soldiers and highly-motivated leaders. In1915, the CEF organization exploded. By early 1916, the initial 18 battalions at Valcartier had become 270 battalions, each needing 30 or more officers, not to mention the officer needs of artillery batteries, engineer companies, and a score of mounted rifles regiments. One of the new battalions, the 148th, was commanded and organized by Colonel Magee, and recruited essentially through McGill, with a focus for Montréal anglophones. The headquarters were established in the old high school on Peel Street, and a yellow card with a small mirror was posted around the campus." This man is wanted by the 148th Battalion," it declared to whatever face appeared in the mirror. Like most of the new CEF battalions, the 148th was fated to be broken up for reinforcements in England. Its colours and traditions were entrusted to the University. Magee himself returned from the war with a Distinguished Service Order (DSO), joined McGill's Board of Governors in 1939, and served as an advisor to the Minister of National Defence in the 1940s.23

Why Don’t They Come?... CWM 19880262-001, © Canadian War Museum

Two siege artillery batteries were also recruited at McGill – the 7th in 1916, and the 10th in 1917 – on the argument that officers in the heavy artillery had a professional need for McGill's mathematical expertise. Probably the best-known survivor, Sergeant Brooke Claxton, reserved his greatest gifts for the practice of law and politics as Minister of National Defence in the Louis St. Laurent government, and as the founding Chair of the Canada Council. Late in 1918, too late for the war, Ottawa recruited a "university tank battalion," to which McGill contributed 26 officers and 186 non-commissioned members.24

While COTC came chiefly from Arts, Sciences, and Engineering faculties, almost everyone associated with McGill felt compelled to join the war effort. Women who had learned how to drive offered to operate ambulances, and to replace male chauffeurs, so they could enlist. Others studied first aid and qualified for the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). Helen Reid, one of McGill's earliest women graduates, became the central figure in Montréal’s branch of the Canadian Patriotic Family, a charity established to raise funds for soldiers' families – often left destitute while the Militia Department struggled with the paperwork involved in providing them with a separation allowance.25

In all, McGill official historian Stanley Frost reported, over 3000 McGill students and alumni enlisted in the war; of this number, 383, or 12 percent of them, died.26 Despite the OTC, most McGill students began in the ranks. By 1917, the Canadian Corps found most of its officers from its own ranks. Combat experience and demonstrated leadership were more reputable qualifications than a signature by a militia colonel approving a commission for the son of a family friend. Two members of McGill's university community, Captain F.A.C Scrimger, and Private Fred Fisher, earned the Victoria Cross. Colonel John McCrae, dead of pneumonia in 1918, left us Canada's best-known poem, In Flanders Fields.

The war cost Canada about 65,000 young lives, and left as many permanently mutilated in body and mind, not to mention about 30,000 war widows and their orphans. Canada was deeply divided, profoundly in debt, and only partly cured of the belief that protecting Britain's Empire was the country’s first duty. The huge and unexpected cost of the war, as well as its shabby results, deterred most Canadians from embracing collective security under the League of Nations.

VAD Nursing Members…, CWM 19920143-009, © Canadian War Museum

Between the Wars

Despite its limited wartime role in officer production, McGill's COTC was reinstated in 1920 as a source of officers for all three of Canada's post-war armed forces. That year, the Conference of Canadian Universities sat through an earnest lecture from Colonel Magee, who insisted that officers raised from the ranks lacked the social breeding or the intellectual energy to match university students. University-based OTCs, he insisted, must be part of Canada's future. Potential infantry and cavalry officers, he explained, needed the most training. Since arts students had the lightest course load, they were the most suitable candidates. Engineers and doctors were a different case. He made no reference to his fellow lawyers.27

After the war, the ardent militarism that had fuelled the COTC's birth had largely evaporated. Chosen in 1919 to succeed Peterson because of his wartime services to the Empire, Auckland Geddes chose instead to remain in Lloyd George's post-war government, and to become Britain's ambassador to Washington. He was quickly replaced by an even more famous wartime figure, Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, whose prestige as commander of the Canadian Corps compensated for his lack of any academic diploma. Veterans filled McGill classrooms, and Currie brought a commitment to learning and remembering students' names, and a firm sense of his authority when bullied by wealthy members of the McGill Board. He was less successful in persuading post-war governments to honour the wartime pledge of $100,000 to build an armouries and drill hall for the McGill COTC.28

Despite Colonel Magee's stirring challenge, like most of Canada's armed forces between the world wars, COTC contingents struggled with apathy and ridicule. Most militia commissions carried little prestige, the training was repetitious and boring – and it had to be cheap. COTC members drilled in McGill basements, or at Mount Bruno, and spent their summers in tents at Farnham or at Mount Bruno. One interwar member, Ben Mendelsohn, remembered joining in 1934, on his father's advice that Germany would provoke another war and it would be good to know something about the army. In May 1939, Mendelsohn found himself a job, quit McGill and the COTC, and added his name to the reserve of officers as a lieutenant.29 On 10 September 1939, the day Canada declared war, the McGill contingent boasted only 39 members.

Let’s Go...CANADA!, CWM 19890094-006, © Canadian War Museum

The Second World War

By most standards, Canada was significantly less prepared for the Second World War than it had been for the First World War. Its chief asset was a set of precedents, and the thousands of middle-aged veterans who had shared them. Principal Douglas, an American, resigned on the eve of war, and the leadership offered by Principal Peterson in 1914 was missing. By 12 September 1939, McGill's contingent boasted just 85 members. Colonel A.A. Magee took over as acting commanding officer and promptly summoned ex-CEF officers and RMC ex-cadets to plan training courses for instructors. Establishment strength was set, as in 1914, at a thousand cadets, plus 150 more from the Macdonald College campus on Montréal’s West Island, where McGill had located its faculties of Agriculture, Education, and Home Economics. Construction of Currie Hall, McGill's long-awaited gymnasium and drill hall, began that autumn. Magee's efforts led to a machine-gun course being delivered by Montréal’s Royal Canadian Hussars in their own armoury. The CO of the Hussars, Colonel W.C. Nicholson, boasted that 30 veterans had switched business suits for old trousers and sweat shirts to relearn old skills. "It does your heart good to see them," he told The Montreal Herald. "They are bubbling over with enthusiasm and anxious to get right down to business. It is remarkable how quickly they pick it up after such a long lay-off from machine gunnery."30 Montréal alderman J. Alex Edmison announced that Queen's University graduates could form a platoon of the McGill COTC if enough of them volunteered.31

By October, enrolment had reached 700, consisting of 395 graduates and 305 undergraduates. The official strength was limited to the 1914 figure of a thousand, with a further contingent of 150 members from Macdonald College. By the end of 1939, total strength had climbed to 1175 members as the grim reality of the war slowly captured minds. On 13 September, for example, the McGill football team interrupted practice to allow some members to perform military drill. By 26 September, the entire team had agreed to drill. In November, the Graduate Society spent $1,200 to give the somewhat ragged university band new uniforms, a white shirt and trousers, a red cape and hat, "…smart but not gaudy and serviceable in all kinds of weather," the Society assured its members, and then urged band members to join the COTC en masse. The band accepted the uniforms, but politely refused to enlist.32 On 4 November, the COTC was a conspicuous presence at Molson Stadium when McGill footballers defeated their counterparts from Queen's University. At the end of the game, the COTC formed up on the field and marched past, and a distinguished former McGill professor, Major-General A.G.L. McNaughton, designated to command Canadian soldiers overseas, took the salute. In November, the Montreal Star reported that 400 McGill cadets, including a hundred from the Macdonald campus, "…had been knocked almost dizzy by camouflage and tear gas" during a tactical exercise organized by the Royal Canadian Dragoons near their barracks at St-Jean. A platoon of Dragoons, hidden in a forest, demonstrated field craft skills to astonished journalists and COTC cadets. 33

Yousuf Karsh/Library and Archives Canada/PA-034104

General A.G.L. McNaughton, General Officer Commanding of the 1st Canadian Division, 1939.

From the outset, the COTC at campuses across Canada were expected to train officers, not just recruits. Colonel Magee's message in 1920, that officers from the ranks lacked the social polish or intellectual energy for their role, had apparently been accepted at Militia Headquarters. To provide facilities, McGill had used Principal Currie's death in 1933 to find funds for a badly-overdue armoury and gymnasium, as well as for a functional memorial to the university's war dead. Construction began in the autumn of 1939. As a war economy replaced the Depression, the estimated cost of the structure, $280,000, had risen to $294,000. Lady Strathcona had contributed $100,000 for the building, and McGill's Graduates Society had committed $175,000. As costs soared, the alumni discreetly boosted their gift to $189,000 to cover the over-run. For their part, the contractors pledged to hurry completion. Once finished, Currie Hall provided the biggest armoury drill floor in Montréal. The first year of the war ended with day and evening reviews of the COTC by McGill's new principal, Dr. Cyril James. Colonel Magee commanded both the day and evening contingents, and the contractors laid rough planks as a hurried substitute for the eventual flooring.

Should McGill's COTC provide academic specialists to different branches of the army? Magee organized the 1939 COTC in eight companies, creating distinct platoons and sections for those seeking commissions in the infantry, artillery, engineering, medical corps, surveying, the air force, and even cavalry and armoured car units. The artillery cadets moved to the Craig Street armoury, where a militia artillery regiment could demonstrate its equipment and skills.34 The Joint Air Training Plan, better known now as the BCATP, invited McGill to offer faculty and students specializing in mathematics and physics to train future navigators. Half the volunteers came from the COTC, half had not served, but all were honours graduates in mathematics and physics.35

By June 1940, Great War precedents were superseded by apprehensions with respect to Britain's imminent defeat. Most people added Blitzkrieg to their vocabulary. William Lyon Mackenzie King, the Liberal Prime Minister, telephoned President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and, as confirmed by a press release from Ogdensburg, New York, on 17 August 1940, shifted Canada from British protection to a nervous dependence upon the American empire. A National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) established conscription for home defence. If young French Canadians could be forced to serve, so could healthy male McGill undergraduates, unless they were busy learning skills useful to the war effort. The COTC ceased to be optional. The McGill band was now required to join. Currie Hall was delivered, none too soon, complete with a Memorial Hall, where, relatives of dead students were assured, McGill's war dead would never be forgotten. The toll of another war soon grew. Male students could stay in university only if they trained with the COTC, and followed approved courses. Forty conscientious objectors protested and, at the insistence of McGill’s Board of Governors, faced threats of expulsion. Two obdurate students were suspended. When the NRMA eventually conceded the possibility of alternative service, the two were cautiously reinstated.36

By the end of the Second World War, under Lieutenant-Colonel J.M. Morris, McGill’s COTC claimed to have trained 7000 in its ranks, of whom 5568 had volunteered for service overseas. Of that number, 298 died or were killed (more with the RCAF than with the army), and 627 were decorated for their services.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-142430

The Right Honourable W.L. Mackenzie King and General A.G.L, McNaughton with officers of the 1st Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, 26 August 1941.

The Cold War

The post-war ‘victory’ era was short-lived. Ottawa demobilized as fully as it could, and McGill took over the former RCAF base at St-Jean to accommodate a flood of returning veterans in professional programs. Canada returned to virtually the same military organization as in 1939 – a modest regular force of sailors, soldiers, and airmen, as well as volunteer reserve sailors in ‘stone frigates’ across Canada, a semi-trained, largely unequipped reserve army, and an auxiliary air force organized and equipped to do whatever the regulars needed them to do. Wartime officer training programs lapsed. In 1946, a modestly revised COTC and separate University Naval Training Divisions (UNTD) for the navy, and an air force University Reserve Training Program (URTP) suggested that almost all officers for both regular and reserve forces would be university graduates. Members would get most of their training in two successive four-month summer camps provided by their respective service or branch. During the academic term, would-be officers would spend an evening a week at drill and attending lectures.

McGill's wartime COTC was formally disbanded in 1946. All serving officers and candidates were struck off strength; stores and equipment were returned. The reformed COTC would serve only the army. McGill's peacetime COTC cadre permitted a lieutenant-colonel and his second-in-command, three majors as instructors, and a captain, posted from the army's Active Force, as the Resident Staff Officer (RSO). The other services provided comparable staff support for their cadet contingents.

Enrolment for the new COTC began late in the summer of 1946. Two hundred applied, but, thanks to strict branch quotas, only 101 cadets were accepted. The Medical Corps had 17 cadets, the infantry only 11 and five chose the signals profession. Two-thirds of those enrolled were war veterans. In a decision particularly damaging to McGill and other Quebec and Maritime universities, Ottawa insisted that, as well as the ability to manage both the university's academic requirements and up to 40 hours of military training per term, the educational prerequisite would be senior matriculation, as provided by the provinces west of the Ottawa River.

Cadets also had to demonstrate ‘Good Fellowship,’ presumably through a McGill COTC Officer's Mess, created in Currie Hall during the war as a vital element of officer training. The mess continued in peacetime. Former and future COTC officers could join what was, in effect, a campus-based drinking club. So could university officials who joined the 3946-XO Association, managed by Major E.L. Greenwood.

The activities, management, and annual general meetings of the McGill Officers' Mess dominate the contingent's post-war archives. A thick correspondence records the reluctance of the Department of National Defence (DND) to reimburse McGill for the space allocated to the COTC mess. Peter Rehak, a distinguished McGill-educated journalist, owes his place in McGill's COTC archives to a photo during a mess dinner, described as, "…just before Rehak fell off his chair." The mess, inconceivable in the days of Sir Sam Hughes and a more puritanical era, had been unthinkable before the war. Now it became a core feature of military life at McGill, complete with cocktail parties, mess dinners, and an annual regimental ball. In return, and with some reluctance, DND rented the premises in Currie Hall from the university.37 COTC members were reminded that King’s Regulations forbade guests from paying for their own drinks. A host must meet the expenses of those he invited to the premises. If the mess was loaned to another organization, COTC members were strictly excluded. Although a ladies committee was thanked for refurbishing the mess and its furnishings, it remained an all-male club until the 1950s when first the RCAF, and then the other services, cautiously accepted women in their commissioned ranks. The mess in the Currie Gymnasium also housed a military library, where COTC cadets could borrow pamphlets and military texts on their parade nights.

Summer training paid COTC members the equivalent of a second lieutenant's salary for three months.38 Added to 16 paid days during the winter, it was enough for a frugal student to meet tuition and living costs for the ensuing academic year. Two years of training qualified a cadet for the lowest officer rank. After the Cold War began, and Canada kept a front-line brigade in Europe, a select few cadets spent a third year overseas with a unit of their chosen branch, sharing more realistic manoeuvres, and seeing the sights of Western Europe. Another preoccupation of the post-1945 McGill COTC was rescuing its regimental funds from DND, which had swallowed them in the 1946 reorganization, and then paid part of the sum to the university to maintain war memorials on McGill's two campuses. The balance of the accumulated funds ($41,560.00 in 1949) was held as a trust fund, "…to be expended in the interests or for the benefit of the McGill University Contingent, COTC or its successors."39

The prolonged Cold War provided a rationale for the COTC and its counterparts, but staff officers had no trouble detecting apathy and indifference to the minutiae of internal administration, and such activities as a sports program organized for Montréal’s reserve units. A baseball team ‘proved a hard sell’ to a unit whose members were scattered across Canada during the warmer months. A rifle team proved rather more competitive. While the strength of the three services' cadet contingents varied, the venerable COTC was, by no means, the largest of the three. In 1956, for example, group photos reveal 48 COTC cadets, 49 members of the University Naval Training Division (UNTD), and 135 officers and flight cadets in Wing Commander C.D. Solin's University Reserve Training Program .40

Disbandment in 1968

On 1 May 1968, all university-based officer training programs ceased across Canada. Lieutenant-Colonel W.E. Haviland, the last commanding officer of the McGill COTC, insisted that the decision had nothing to do with the controversial government program to unify the three armed forces, but it was an economy that Unification made easier for all three of them. Nor was it due, as some contemporaries would allege, to Pierre Elliott Trudeau, whose selection as both Liberal Party leader and prime minister came a month after the decision was taken. No doubt, of course, that the decision had his assent. What is a little astonishing for a program that helped many students finance their university experience was the absence of dissent or even interest. In its last appearance in Old McGill, the graduating students' yearbook, the COTC mustered four officers, a sergeant-clerk, and only eight cadets. The McGill URTP squadron also displayed four officers and 18 cadets – one, a smiling young woman upon whose bosom a handsome young man in the back row has placed a possessive hand.41 Cadets from McGill's Naval Training Division did not even make an appearance.42

CFJIC photo 288-IMG0006

Second Lieutenant Ray Hache, COTC, watches a member of 4 Field Workshop, RCEME, repair a motor, June 1960.

The need for economy was a major argument for unifying the three Canadian services. Coming together reminded the three formerly independent services that university-based officer training had not given great value for the money. Staff and facilities needed to maintain scores of contingents across Canada and to provide specialized summer courses at virtually every service or branch training facility. The 1960s were a time of student radicalism and political dissent north and south of the 48th Parallel, and many American universities had disbanded their reserve officer training contingents or ROTCs to remove a target for campus militants. The 1912 militarism which had brought the COTC to life at McGill was as faded a memory as the 1915 demand from the McGill Daily that Ottawa hurry up and give students a way to offer up their lives for King and Empire. Those who mourned the closing of the officers' mess would hardly stage a demonstration at McGill's Roddick Gates. On 3 February 1968, 68 COTC veterans met at the mess in the Currie Gymnasium, including four ‘originals’ from 1912, as well as Brigadier J.A. De la Lanne, commissioned from the ranks in the First World War, and the winner of a Military Cross and Bar. De la Lanne had become a successful chartered accountant and had served as the Canadian Army's Vice-Adjutant-General in the Second World War.43 After 56 years in being, the McGill COTC was history. The Memorial Hall was soon forgotten, and, because the ground had heaved under the Memorial doors, it became inaccessible. Despite the solemn rhetoric of remembrance, or even the COTC Volunteer Memorial Fund, McGill's administration felt little pressure to pay for repairs. Whatever the rhetoric of 1940, the university had even allowed Remembrance Day to lapse until students themselves organized a service in 1994.44

CFJIC photo 288-IMG0036

Second Lieutenant Merchant, COTC, serving in Europe with 1st Battalion, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment of Canada), leads a patrol past a German windmill, July 1960.

![]()

One of Canada’s most distinguished historians, Desmond Morton, OC, CD, FRSC, went to McGill in 1994 as founding director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada. The author of forty books on Canada's military, political, and industrial relations history, he is currently Major Hiram Mills Professor of History Emeritus at McGill and a Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Toronto.

Notes

- This article began life as a presidential lecture to the James McGill Society, an organization devoted to preserving McGill's history. I cheerfully acknowledge the assistance of Gordon Burr and the staff of McGill's Archives, and of a number of former COTC members, and, most particularly, the support of the university's historians, Dr. Stanley Brice Frost and Dr. Peter McNally.

- On this development, see R.A. Preston, Canada and "Imperial Defence" (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967); and Norman Penlington, Canada and Imperialism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965).

- .On the cadet movement, see Desmond Morton, "The Cadet Movement in the Moment of Canadian Militarism, 1900-1914," in Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol. XIII, No. 2, pp. 56-62.

- James L. Hughes, "Drill in Schools," in The Canadian School Journal, Vol. I, No. 7, December, 1877, p. 112.

- Armand Lavergne, "National Defence as Viewed by French Canadians," in Proceedings of the Canadian Military Institute, 1909-10, (19 November 1910), p. 99.

- This origin is claimed by Colonel A.A .Magee in his Address to the Conference of Canadian Universities at Quebec, 18 May 1920, pp. 1-2.

- On Geddes, see Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) XXI, p. 693; and Stanley B. Frost, McGill University: For the Advancement of Learning, Vol. II, pp. 99, 109.

- Andrew Macphail, "Theory and Practice," in University Magazine, XII, October 1913, p. 196.

- On the formation of the Canadian Defence League, see Morton, "The Cadet Movement," pp. 62-63 and following pages.

- Ibid., pp. 62-63. The donation helped inspire the formation of the CDL in Toronto. See its periodical: Canadian Defence, Vol. III, No. 7, January 1912.

- See Desmond Morton, A Military History of Canada (Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 2007), 5th Edition, pp. 126-127. Laurier's defence minister, his cousin, Sir Frederick, urged Hughes' selection despite the prime minister's deep misgivings. Under the Liberals, Hughes had been promoted to colonel and had powerfully influenced the selection of the Ross Rifle, a fact the Liberals enthusiastically exploited when its many defects became apparent.

- McGill Daily, 2 October 1939, p. 1. <

- Old McGill, Vol. XVII, 1914, p. 194.

- Hutton interview, in Toronto Globe, 12 December 1913.

- McGill Daily, 10 January 1915.

- An early and painful fall from his horse left Geddes no alternative to staff duties at BEF headquarters. By the end of 1916, David Lloyd George had placed him in charge of Britain's national service system, after insisting that he serve as a newly-elected MP, not as a medical doctor. He used his position to prioritize the labour needs of war industries, and to deplore the heavy casualties imposed by the British Army's generals. He remained part of the government until McGill's Board of Governors chose him as a successor to an exhausted Principal Peterson. Geddes insisted upon remaining in Lloyd George's Cabinet, and became British ambassador in Washington. (Oxford DNB, Vol. XXI, p. 693.)

- McGill Daily, 4 November 1914. Hughes' announcement led to a modest controversy, inspired by the pro-Liberal Montreal Herald. At the time, the traditional 50-man militia company, up to eight to a peacetime battalion, had been replaced by the British with battalions of four double-sized companies. Each organization required a distinct drillbook. The original CEF had reorganized twice, even before it left Valcartier. Had McGill been given the right or wrong drillbooks? The Herald hoped for a scandal. McGill's leaders refused to play.

- McGill Daily, 6 November 1914.

- Ibid., 1 October 1914.

- Ibid., 4 February 1915.

- Molson was not just the scion of the prominent brewing family. He had also been an outstanding athlete and student during his McGill years. Killed by a German artillery shell in 1917, he left McGill $75,000 to construct the badly-needed football stadium that still bears his name. See Frost, McGill, Vol. II, p. 103

- They were recalled by Maurice Pope, a McGill-trained engineer, serving overseas with the CEF. See M.A. Pope, Soldiers and Politicians: The Memoirs of Lt. Gen. Maurice A. Pope CB, MC, (Toronto, 1962).

- On Magee, see The Canadian Who's Who, Vol. XI, 1957, p. 688; and Obituary, McGill News, Fall 1961, p. 21.

- Frost, McGill, Vol. II, p. 99.

- On Reid and family issues, see Morton, Fight or Pay: Soldiers' Families in the Great War (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004).

- Frost, McGill, Vol. II, p. 101.

- See Lieutenant-Colonel A.A. Magee, "Address to the Conference of Canadian Universities at Quebec City," 18 May 1920, pp. 1-10.

- See Frost, McGill, Vol. II, p. 123. By the time Ottawa had issued a clear refusal, other funds collected by the university for a gymnasium had been spent, and the advent of the Depression spelled an end to such a project, until the death of sir Arthur Currie at the end of 1933 raised the need for an appropriate memorial.(Frost, Ibid., Vol. II, p. 223.)

- Mendelsohn's account was provided by Wes Cross of the McGill Archives from the McGill Remembers website.

- Montreal Herald, 27 September 1939.

- As announced by Ibid., 21 September 1939.

- McGill News, Autumn 1939. Embarrassed to admit the band's refusal to conform to McGill's alumni's wishes, the editor cheerfully predicted: “…[that] it is expected that within a year or so, it will be accepted."

- Montreal Star, 23 November 1939.

- McGill Daily, 9 November 1939.

- Ibid., 19 December 1939.

- Frost, McGill, Vol. II, p. 219.

- The negotiations provide a constant theme to the Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of the Mess Committee. See McGill Archives, COTC, 1 March 1947 and 14 October 1947.

- Judge Keith Ham remembered earning $165 a month in the early 1950s as a cadet in the Royal Canadian Artillery. He travelled to Shilo, the RCA School, by delivering a new car from Oshawa or Windsor to its new owner in the west.

- COTC Annual General Meeting, 21 March 1949, Page 2. (According to Colonel J.M. Morris, the former commanding officer, the funds had been contributed by members transferring their pay to the contingent during the early years of the Second World War, when the contingent was penniless, to help create a COTC Volunteer Memorial Trust as a contribution to a memorial hall in the Currie Gymnasium.)

- Old McGill, 1956, pp. 113, 370, and 374.

- Ibid., 1968, p. 285.

- See complete Old McGill, 1968.

- McGill News, Vol. XLIX, No. 2, March 1968.

- An early service of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada was to provide a piper from the Black Watch after students had made a request for assistance.