This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

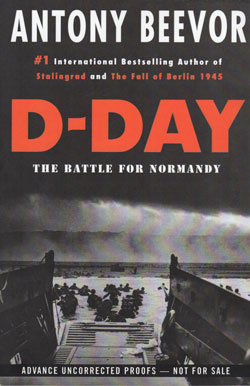

D DAY: THE BATTLE FOR NORMANDY

Reviewed by Mike Goodspeed

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

D DAY: THE BATTLE FOR NORMANDY

by Antony Beevor

New York: Viking USA, 2009

608 pages, $41.00

ISBN – 10:0670021199

ISBN – 13:978-0670021192

Reviewed by Mike Goodspeed

There is certainly no dearth of good accounts of D Day or the Battle for Normandy. So when asked to write a review of Antony Beevor’s D Day: The Battle for Normandy, I was more than a little skeptical. Surely this ground had been intensively ploughed over by John Keegan, Max Hastings, our own Mark Zuehlke, and scores of others. Moreover, was there really a new dimension to the Normandy campaign that had not already been carefully examined? I was pleased to discover that Beevor has successfully created a companion piece that is not only highly readable, but valuable for its insight and understanding of this critical period of history.

Perhaps the most persuasive reason for reading this book is that Beevor has an inimitable flair for simultaneously capturing both the spirit of men at war and the larger strategic and operational situation within which they find themselves. Beevor changes his focal length repeatedly – from the individual experience of the shock of battle to the broader disposition of the campaign. He is not the world’s best-selling military historian by accident, and, in D Day, Beevor again displays his distinctive technique of personalizing his subject, all the while effortlessly maintaining his eye on the campaign’s larger context. Beevor mesmerizes the reader with intriguing detail, and, at the same time, provides a readily understood overview of the cut and thrust of the big picture.

Recommending this book in the first instance on the basis of Beevor’s style might seem a touch superficial in a professional journal but his technique not only speaks to the character of the intended audience, it also indicates something about his implied purpose in writing the book. Much of Beevor’s work reflects a concern with simplifying and synthesizing the experience of massive battles in order to gain an appreciation of the complete spectrum of a particular campaign. In this book, Beevor strives to demonstrate not only the grand design of the fight for Normandy, but also the quality and character of the individual soldiers and leaders. By giving the analysis of the campaign an intensely personalized focus, Beevor addresses himself to several groups: the professional historian, the serious student of military art, and the average reader who is looking for an entertaining and informative diversion. He describes the experiences of generals, junior leaders, soldiers, and civilians living on the battlefield, and he is successful because his writing is unadorned and succinct; and, his unobtrusive commentary smoothly bridges one narrative line with the next.

Much of the detail Beevor uses to tell his story is fresh, as he has drawn upon the resources of more than 30 archives, and gone to considerable effort to capture the experiences of previously unpublished sources. His wide-ranging use of original reference material gives the book an absorbing and vivid storyline, and because of this, Beevor’s D Day has become immensely popular. Its current popularity makes it no less instructive to the professional soldier, for Beevor does not sacrifice hard analysis for lavish description. Instead, his approach to military history is a graphic one that leads the reader to his own conclusions. Beevor carefully frames his opinions and judgments within his narrative, and, in doing so, he has given his book a more appealing flavour than many more conventional academic histories.

The title, D Day: The Battle for Normandy is something of a misnomer. Beevor concentrates most of the book not on the events of the day of the invasion itself, but upon the entire Normandy campaign; and in the last quarter of the book, he sweeps the reader along to the Liberation of Paris. Although the title may be misleading, this is a story that focuses almost exclusively upon the clash of arms. There is virtually nothing mentioned of the political manoeuvring preceding the invasion, or the Herculean staff planning efforts that made the battle for Normandy possible. Given the quality of the elements that Beevor has addressed, it is a shame that he chose not to examine these other crucial aspects in greater detail.

In terms of what is new or innovative in this book, two themes set Beevor apart from other successful works on the subject. The first is that he has closely examined the effects the campaign had upon the French population. In this he has portrayed the civilian population of Normandy as being one of the principal actors in the struggle. Beevor graphically illustrates the suffering that the French endured – for example, on the actual day of the invasion, there were more civilian casualties in the towns and villages adjacent to the beaches than the Americans endured on their ill-fated and bloody seizure of Omaha Beach. By peppering his account with the agonies and misfortunes suffered by the French, as well as judiciously inserting revealing asides on General Charles de Gaulle’s difficult personality, Beevor subtly suggests that the long-term effects of the Normandy campaign played a major role in France’s self-imposed isolation during much of the Cold War.

The second distinctive theme that Beevor introduces in this book is that the Normandy campaign was one punctuated by the brutal and illegal killing of prisoners on both sides. Beevor is certainly no apologist for German atrocities, and he does not intimate that there was some kind of moral equivalence shared between the Allies and the Germans. In fact, he is unsparing in his description of reprisals and slaughters inflicted upon the civil population, largely by SS units. But Beevor suggests, at least obliquely, that the nature of high-intensity, high-stakes battle does not always follow the rules of war.

In this book, Beevor repeatedly depicts the struggle for Normandy as being at least as savage, bloody, and pivotal as any major battle on the Eastern Front. On more than one occasion, he appraises the intensity of the fighting by examining casualty rates, and finding that, on a divisional basis, the fighting in Northwest France was probably more intense than that on the Eastern Front. What Beevor does not comment upon directly, but it jumps off the page, is the period’s grim acceptance of mass casualties. Unlike our own era, where societies are buffered by their armies and where professional soldiers fight limited wars, the battle for Normandy was an existential fight – with both sides understanding that whoever lost the campaign would not only lose the war, but forfeit the basis of their social and political order.

An element of D Day that begs mentioning is that Beevor is a brilliant caricaturist. His book is worth reading almost on this basis alone. In just a few quick phrases, Beevor captures the essence of a personality: Eisenhower smoking four packs of cigarettes the day before the invasion; Montgomery energetic and vain, insisting that everything had gone precisely as he had planned; Kluge railing at his headquarters; or an untested battalion commander trying desperately to energize frightened troops. On every page, Beevor brings to life the personalities and the atmosphere of the campaign.

From a Canadian perspective, Beevor generously gives credit where it was due. He has high praise for the quality of Canada’s junior officers, the Canadian Army’s abilities, and its dogged toughness. He is only slightly more reserved in his enthusiasm for our most senior officers – although he puts the blame squarely on Montgomery for not closing the Falaise Gap. In an interesting aside, Beevor shares the civilian Canadian’s obsession with trying to define our national character. He comes to the conclusion that we had British traditions and an American disposition, and, perhaps on this point, he misses the mark. Defining character is an elusive undertaking; but anyone who has ever served in the Canadian Forces has never had a problem understanding the differences between Canadian and American temperaments.

There are many excellent features of this book. It is balanced, well-researched, well-written, and, in its unique way, it is a penetrating examination of the fight for Northwest France. It is as good a study of the campaign as has been written.

![]()

Lieutenant-Colonel Michael J. Goodspeed, an officer in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), is currently Deputy Chief of Staff for Learning Support at the Canadian Defence Academy in Kingston.