This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Book Reviews

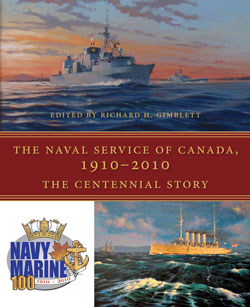

THE NAVAL SERVICE OF CANADA 1910-2010: THE CENTENNIAL STORY

Reviewed by Jurgen Duewel

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

THE NAVAL SERVICE OF CANADA 1910-2010: THE CENTENNIAL STORY

Richard H. Gimblett (Ed.)

Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2009

230 pages, $ 39.95

ISBN: 978-1-55488-470-4

Reviewed by: Jurgen Duewel

Richard H. Gimblett, PhD, is a retired naval officer and the Navy Command Historian. In compiling this book, Gimblett has combined the contributions of 13 well- known and respected naval historians to help tell the history of the Canadian Navy. This handsome book not only does a fine job of telling the Canadian Navy's story, but, thanks to large number of photographs, paintings, and colour plates, it illustrates a colourful history, and it is a wonderful overall tribute to the navy's 100th anniversary.

The book is divided into chapters covering important periods in the history of the navy, as well as speculation with respect to its future. Along with the expected chapters dealing with war and peace, readers will be pleasantly surprised to find some unexpected gems. For example, the often neglected topic of maritime research and development is well written by Harold Merklinger, a former defence scientist at the Defence Research Establishment Atlantic (DREA). Merklinger shines a light on some of the unique Canadian contributions to naval warfare – including such marvels as the hydrofoil, the Canadian Anti-Acoustic Torpedo Decoy (CAAT), the Variable Depth Sonar (VDS), the Bear Trap and the Helo Hauldown system, as well as the ubiquitous trackball. Another pleasant addition to the book is the chapter covering naval art of the Second World War by Pat Jessup. This chapter depicts other dimensions of life in the navy during that time, and it serves as a reminder of some the more poignant aspects and experiences of men and women at war.

The book's first chapter describes the events leading up to the creation of the Naval Service by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier on 4 May 1910. As Roger Sarty writes, in 1906 Great Britain launched HMS Dreadnought, the revolutionary battleship that made all other warships preceding it obsolete. The problem for Great Britain was that, suddenly, new naval powers, and specifically Germany, were now much closer to parity in numbers of battleships. The Dreadnought scare of 1909 (fear of German parity by 1912), compelled Great Britain to inform her colonies that they could no longer count upon Britain to look after their maritime defence, as she was pulling back her naval forces closer to home to deal with the emerging German threat. Great Britain also expected her wealthier former colonies, such as Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, to either build their own ships or to provide funding for Great Britain's shipbuilding efforts. Although Laurier had decided that Canada should build its own navy, the Leader of the Opposition (and soon to be Prime Minster), Robert Borden, did not agree, and he preferred to transfer funds to Great Britain instead. Unfortunately, when he came to power, he did neither – the result being that Canada, and consequently her navy, were wholly unprepared for the First World War. Thus the Canadian Navy’s contribution to the war effort at sea was unsurprisingly minimal, and, at times, even comical. For example, we are told of how the province of British Columbia purchased two submarines for the navy, and of how even a private citizen got involved through the donation of an armoured yacht. At one of the lower points of the war for the service, the only ship that had an opportunity to attack an enemy submarine in Canadian waters, HMCS Hochelaga, instead decided to ‘turn tail’ rather than engage the foe.

After the Armistice, things did not look promising for our young navy. Parliamentary debates subjected its performance to public scorn, and even managed to pin some of the blame for the Halifax Explosion of 6 December 1917 on the navy. Bill Rawling does a good job of explaining how the heroic efforts of Commodores Hose and Nelles kept the navy a live, relevant, and coherent force during the interwar years by keeping it in the public eye and by concentrating upon fisheries patrols and search and rescue. The navy also was able to demonstrate its usefulness as an instrument of government policy when it rescued some Canadians trapped by a civil war that had erupted in El Salvador.

The book covers the Second World War in two chapters. Donald Graves does a commendable job of describing the overall campaign and detailing the navy's involvement at Dieppe and the Normandy landings, while Marc Milner covers Canada's part in the Battle of the Atlantic. Milner pulls no punches in his section, detailing how an exhausted, underequipped and over-committed navy had to be withdrawn from mid-ocean convoys from December 1942 until the fall of 1943 in order to re-calibrate itself. However, by the end of the war, Canada's navy had destroyed 33 U-Boats and had forged a viable role for itself.

Although the period from 1945 to 1960 constituted, in many ways, the halcyon days of the Canadian Navy – having on strength two aircraft carriers, two cruisers, and over 30 destroyers and frigates – there were ‘some cracks in the foundation.’ Morale problems resulted in a number of ‘mutinies,’ or, more accurately, as Isabel Campbell describes them, "…work stoppages." Nevertheless, they were serious enough to cause a commission of inquiry led by Admiral Rollo Mainguy. However, in her chapter, Campbell treated these incidents as mere ‘tempests in a teapot,’ and, I believe, missed the mark somewhat by questioning the value of Mainguy's report. The navy's divisional system was born at this time, a system of which the navy is deservedly proud, and which has stood the test of time. The divisional system has not only prevented the navy from suffering any further ‘incidents,’ it has been instrumental in helping to avoid the leadership problems that surfaced in the other branches of the Canadian Forces (CF).

Richard Mayne characterizes his chapter, which chronicles the navy in the 1960s, as the years of crisis. He could have also referred to it as ‘the big reality check.’ The question at the time was whether the navy should remain a largely Anti- Submarine Warfare (ASW) fleet, or expand to become a more balanced ‘general purpose’ fleet. It soon became apparent that the navy's aspirations for a 43-ship fleet, including an aircraft carrier, were not fiscally viable. Mayne goes on to explain that although the navy fought a valiant fight, led by Admirals Rayner and Landymore, against cost cutting and Unification, it was a battle the navy was doomed to lose. Nevertheless, despite the political battles raging in Ottawa throughout the 1970s, the navy continued to do its job at sea, which, in the words of Admiral O'Brien, was "…to find Russian submarines." Ironically, it was at the end of the Cold War, which coincided with the arrival of the new Halifax Class frigates, that the navy became truly a ‘general purpose’ fleet. This was demonstrated by its participation in both Gulf Wars, the War in Iraq, and the continuing campaign against terrorism. The new millennium and the ‘post-9/11’ world in particular would witness Canadian frigates patrolling the Straits of Hormuz, carrying out non-compliant boardings and anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, anti-drug patrols in the Caribbean, and exercising in the increasingly important and ice-free Canadian Arctic.

I believe James Boutilier summed up the future for the Canadian Navy best when he wrote: "The world of 2025 will require a global naval presence more than ever before, whether to combat illegal fishing, the illegal movement of people, and disaster relief…”

Laurier was correct in 1910, and he still is right today. "Canada needs a Navy." Doctor Gimblett has done an admirable job of reinforcing that point, writing a book that should be on the list of everyone who has an interest Canada's history and her navy.

![]()