MILITARY ETHICS

CFJIC 534-IMG0020

Parliament

Ethics, Human Rights, and the Law of Armed Conflict

Louis-Philippe F. Rouillard

Louis-Philippe Rouillard is a graduate of the University of Ottawa (LL.L, LL.M), of the Royal Military College of Canada (BMASc, MA War Studies), and of Peter Pazmany Catholic University (PhD). He has been the Defence Ethics Programme’s Conflict of Interest and Programme Administration Manager since 2008.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Occasionally, there is a view echoed by some ‘operators,’ the ‘real soldiers,’ that the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) does not lend itself to effective application in operations. They view the law devoid of any value in itself. As a result, they act in a manner consistent with the minimal letter of the law, but eschew its spirit. By doing so, their actions might meet the legal requirements to avoid prosecution, but do not fully respect the intent of the law and the values that it encompasses. Sometimes, a given situation does not meet even the minimal requirements. Examples from the last few decades abound, and do not need retelling here. This article will counter that the LOAC is not a ‘stand-alone benchmark’ requiring a minimal ‘pass or fail grade,’ but rather, it is a wider set of law that incorporates the values of professional soldiers and of society-at-large. I will demonstrate this in three parts. First, I will show the link between the LOAC, professionalism, and ethical obligations. Then, I will demonstrate how this translates into firm obligations for service members to conform to legal norms that are applicable at all times, such as international human rights. Finally, I will conclude with a demonstration of the application of ethical values and principles in operations through the prism of the law.

Professionalism, Ethics, and the LOAC

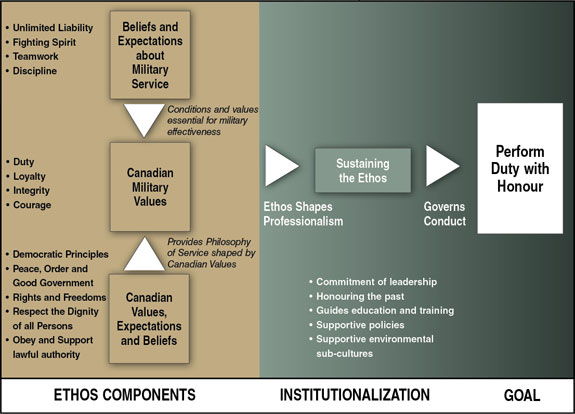

The Canadian Forces (CF) is established under the authority of Parliament through the National Defence Act.1 All its members are subject to the authority of the chain of command, up to and including the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS). 2 Since Canada does not have conscription,3 it is a ‘professional army,’ that is, a volunteer army serving in accordance with terms of service out of which an individual can elect to continue or not, and the institution can decide to re-enrol the individual, or not. This means that an individual member’s constant training gives them a continuous professional development. While the terms of service of the Reserve force is separated by classes of service, the idea of a continuous professional development remains applicable to all service personnel. Duty with Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada affirms that all CF members are professionals by virtue of their Oath of Allegiance. While a debate exists in the academic world as to whether this inclusiveness is warranted, 4 it will suffice for our purposes to adopt Duty with Honour’s criteria, which include acceptance of the concept of unlimited liability, a specialized body of military knowledge and skills, and a set of core values and beliefs found in the military ethos that guides an individual in the performance of their duty.5 This reflects the historical and sociological criteria stated by many theorists regarding the nature of the military profession, including adherence to professional norms.6 These norms are the military ethos, understood as “… the foundation upon which the legitimacy, effectiveness and honour of the Canadian Forces depend,” and of which they consist:

From Duty with Honour – The Profession of Arms in Canada. Canadian Forces Leadership Institute

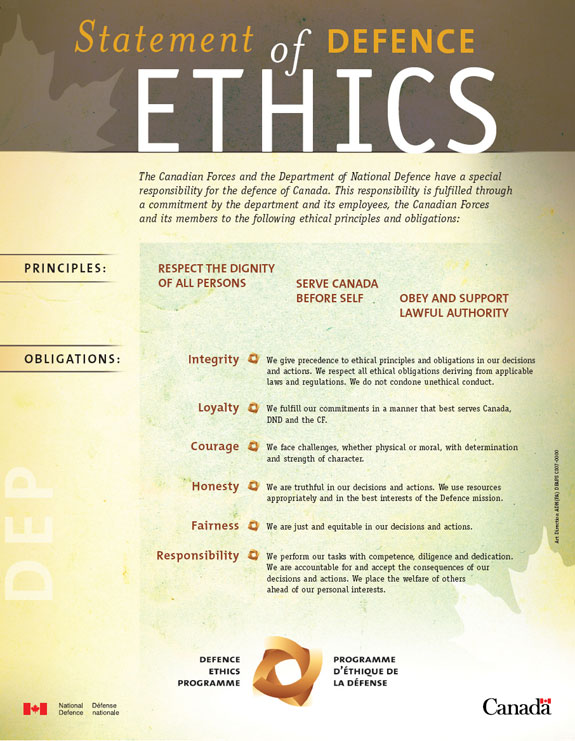

Figure 2-1. The Military Ethos7

This military ethos reflecting national values and beliefs leads to a unique Canadian style of military operations - one in which CF members perform their mission and tasks to the highest professional standards, meeting the expectations of Canadians-at-large.8 This is where the CF differs from many other armed forces. They are not only expected to abide by the military ethos, but also to apply a common set of values it shares with another institution responsible for the national defence of Canada, the Department of National Defence (DND). Established under Article 3 of the National Defence Act, DND exists under the responsibility of the Minister of National Defence, who is vested with power over the management and direction of the CF and all matters relating to national defence.9 Thus, the interaction between the two necessitates a common set of values under which to act. Since DND is composed of civilian public servants who fall under the rules of the Public Service Employment Act,10 they are held to the values of the Public Service (PS) of Canada, as affirmed in the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Service.11 To reconcile the two, the Deputy Minister of DND (DM) and the CDS jointly established the Defence Ethics Programme (DEP) in 1997. The DEP produced a Statement of Defence Ethics,12 which combines both Canadian Military Values and Public Service Values in a set of principles and obligations to which CF members and DND employees must adhere. While the terminology may be different, this alters in no way the fundamental values by which military members must abide in their official duties. For example, if the concept of duty encompasses as much the obligation of responsibility of the Statement of Defence Ethics, the concept of unlimited liability that underlines this obligation for CF members continues to exist. It is only because responsibility does not imply this concept for public servants that the concept of responsibility is accepted as the common shared value of the two institutions. Still, in no way does this abrogate the military values to which serving personnel are expected to conform.

Some past authors argued that military morale and its values have been eroded by the “… transference of civilian values and management techniques to the Forces.”13 However, even proponents of having a different set of values in the 1980s recognised that “… an ethos which resulted in alienation of the Forces from the Canadian public or the civil service is regarded as highly undesirable.”14 There are good reasons for this. The military ethos is composed of, amongst other elements, Canadian values. If it was otherwise, a divide would be created, and the armed forces would be defending Canadian ideals, basing itself upon its own set of values for doing so, and not upon the wider set of beliefs and expectations that the nation’s citizens hold. This is a fundamental aspect of the bond of trust that must exist between all citizens forming civil society, and its citizens in uniform. This trust is a capital, much like money in the bank. Trust is a function of two things: character and competence. Character includes one’s integrity; one’s intent toward and among people. Competence includes one’s capabilities, skills, and generated results.15 Trust equates to confidence. Each time competence or character is tainted by an event, we withdraw some of our capital. When too much is withdrawn, it can result in moral bankruptcy.

This bond of trust between citizens and uniformed citizens impacts upon the ‘social capital’ of a nation, affecting performance, retention, recruiting, and the devolution of resources to the armed forces, further impacting competence and morale. Once in this vicious circle, the bond of trust further dissolves and may take decades to rebuild. An example of this is the ‘military covenant’ between civil society and the military. It originates from the British Army Doctrine Publication 5 entitled ‘Soldiering: the Military Covenant.’16 It is described as the moral basis of the [British] Army’s output. It describes how the unlimited liability makes soldiering unique, and what a soldier should expect for surrendering some civil liberties.17

The Canadian Forces has adopted a similar concept to that of the military covenant, but calls it a ‘social contract.’ Both are understood as a ‘moral commitment.18 As a result, under the terms of the Oath of Allegiance, a CF member can expect fair and respectful treatment, for which society expects an output, including sending its uniformed citizens in harm’s way in order to support government policies. Serving personnel have a reasonable expectation that this will be done with due care and attention.19 If one is injured, one expects to be cared for by the society that required this sacrifice. Yet, commentators speak of an unravelling of that moral commitment20 and a disconnect between the military and society.21 In the same breath, it is argued that Western societies do not like the use of force, as it is by nature antithetical to their liberal outlook, and that if they must enter a fight, their armed forces do so in a manner that reflects their own core liberal values,22 which question the legitimacy of the use of force.23 Furthermore, these societies have become more intolerant of casualties, especially when perceived as being unnecessary due to misguided foreign policies.24

A proposed answer to this new framework is that society’s expectations have increased and are now on par with its education, 25 making its own judgement on the use of public resources. This includes prudence and legitimacy prior to entering conflicts, and expectations that the conduct of military personnel in a conflict will conform to society’s values. Such values must form part of the armed forces’ values, and the military cannot depart from them or the social contract would be nullified. The application of these values for armed forces therefore becomes military ethics: the right and wrong actions of an armed force, and its very real consequences upon human lives.26

In the past, societies have expected its military to behave with honour, but nonetheless, have often ‘turned a blind eye’ to less-than-honourable behaviour.27 But societal expectations have grown; hence military ethics, a species of the genus of professional ethics.28 As with any other professional ethics, one criterion for its existence is that it answers to a specific conceptual framework, including a legal and regulatory cadre. For military ethics, this legal framework is formed by the LOAC. Yet, ethics concerns itself, not with the legality of an action, but with the notion of knowing whether this action is morally right or wrong. Since law is not concerned with the right or wrong of an action, but solely with its legality, how does one reconcile the two?

DND Photo

Statement of Defence Ethics

Military Ethics, the LOAC, and Human Rights

The LOAC is not a new concept. The customary approach to law taken through religious text, 29 has underlined the morality – or ethics – to apply to battlefield situations, even in ancient times.30 Throughout history, a tradition of ‘Just War’ evolved, comprised of two sets of principles: one governing the resort to armed force (jus ad bellum), and the second governing conduct in hostilities (jus in bello).31 While a tradition and not a law, based upon the attempts of philosophers to describe its provisions, it has shaped much of Western military doctrine.32 Therefore, following the precepts of the Just War tradition, and adapting to the formal legal context of the post-Second World War, the use of armed force is now more under scrutiny than ever – both for entrance into a given conflict, and for conduct during hostilities.

This flows from the consequences of the Second World War, but also in a large part from its preparatory phase, preceding the entrance of the United States into the conflict. The then-President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, had announced in his Annual Message to Congress on 6 January 1941, his concept of “Four Freedoms”: freedom of speech and expression everywhere in the world; freedom to worship God in his own way everywhere in the world; freedom from want, meaning economic security and healthy peacetime life for all inhabitants everywhere in the world; and freedom from fear, translating into world-wide reduction of armaments so that no nation should be capable of physical aggression.33 This statement of an implied act of support for the United Kingdom clearly demonstrates a policy that the Americans intended to pursue. It did not remain as a message to Americans. On 10 August, 1941, Roosevelt met with Prime Minister Winston Churchill off the coast of Newfoundland. From their ‘meeting at sea’ emerged, on 12 August 1941, the Atlantic Charter, which became, for all intents and purposes, the policy statement of the entrance into war of the United States.

Its clear statement of alliance of the Anglo-Saxon world is undeniably made against “aggression” and the “Hitlerite Government of Germany,” calling “… after the final destruction of Nazi tyranny (…) assurance that all men in all lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want” and that respect for “the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live.”34 This might seem a simple declaration, but as American historian and lawyer Elizabeth Borgwardt has declared, when you state a moral principle, you are stuck with it. And here, the Atlantic Charter affirmed the rights as they apply, not to States, but also to “peoples,” and to “all men in all the lands.”

It is important to remember that the United States was not yet officially part of the hostilities, but already the Atlantic Charter established the moral justification for supporting the United Kingdom. This justification was not intended for States to enjoy prestige, or to dominate, as classical realism would desire it relative to international relations’ theory. Rather, it was a statement to provide collective security and personal enjoyment within this prospective system. Through a liberal approach, it was building the argument as to the justness of the entrance into war when the time would come, answering to the jus ad bellum principle of the Just War tradition.

The question, then, is not the legality and/or morality of entrance into a conflict, since this has been answered, but the conduct of the hostilities under jus in bello. Its accepted benchmark is the LOAC, and it provides a set of rules as to the manner in which one may cause harm to physical integrity, including the arbitrary denial of the right to life, as well as harm to property, both private and public. Its whole premise rests upon the principle of humanity, and this is enacted by something seen as “a triumvirate equation under which military necessity is framed by the prohibition of unnecessary suffering during the proportionate application of military force, in an effort to ‘humanize’ a reality,”35 raising the concept of humanity as grounds for a fight. The Atlantic Charter provided for a statement of political rights as core values of the reason why the war would be fought, a vision of individuals in a new system of collective security as opposed to the previous one composed solely of the interests of states and emphasising the application of these principles domestically as much as internationally. All these elements “continue to inform our conception of the term ’human rights.’”36 The Allies defined its war in terms of humanity; a fight for human rights. The Axis did not. Therefore, the Allies gained the higher moral ground from which to operate.

At its roots, the principle of humanity rests precisely upon the very first right of “all men in all lands”: the right to life. The status of “men,” understood as “persons” in the Just War tradition, is woven into the LOAC in the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, the latter of whom pose no threat.37 Yet, as opposed to international human rights where the right to life cannot be arbitrarily denied, 38 the LOAC does provide for arbitrary deprivation of this right. This applies to combatants and non-combatants alike through the criteria of proportionality, whereby an attack on combatants that is deemed a military necessity becomes justifiable if it provides for economy of force, even if collateral damage in terms of non-combatants is expected. The criteria of proportionality, demands that the military advantage gained from the attack is superior to the expected non-combatant casualties. With respect to the realities of combat where miscalculation occurs and/or collateral damages are much greater than anticipated, these are not at issue: it is the expectations prior to an attack being executed that matter. As long as non-combatants were not directly targeted and the expectation of proportionality was respected, it is permissible to deny arbitrarily non-combatants of their right to life.39

Here is where the professional soldier must think beyond the narrow confines of the LOAC, even though he is trained precisely in its application in the course of his professional activities. A professional soldier must remember that, while subjected to the LOAC, the professional also remains an agent of the State, and must continue to apply international human rights laws, which are not suspended from their application during an armed conflict, with the exception of the provisions that are permitted to be suspended under customary and treaty law, and that have been clearly stated as being suspended.

For Canadian Forces members deployed abroad, the LOAC certainly applies, but so does the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It clearly states that certain rights continue to apply, even in times of public emergencies threatening the existence of the nation. Among these, the right to life is paramount. Some positivists argue that the Covenant only applies to “…State Party to the present Covenant [and thereby has them] undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant.”40 Their interpretation of this sentence is that both conditions must be in force for the provision of the Covenant to be applicable.41 In true–but-debunked Alberto Gonzalez fashion,42 this interpretation conveniently ignores previous decisions by the United Nations Human Rights Committee, which is the international body responsible for the implementation of the Covenant, clarifying this sentence and affirming: “… a State party must respect and ensure the rights laid down in the Covenant to anyone within the power or effective control of that State party, even if not situated within the territory of the State party.” Further, that the International Court of Justice in its advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territories recognized that the jurisdiction of States is primarily territorial, but concluded that the Covenant extends to “… acts done by a State in the exercise of its jurisdiction outside of its own territory.”43

DND Photo

Duty with Honour cover

The International Court of Justice’s decisions are binding for states having accepted its jurisdiction. As a result, one is to accept the concept that the Covenant is indeed binding on States, even outside their territory, where they have anyone within their power or under their effective control – even if not situated within the territory of the state at concern.44 This includes counter-insurgency operations after an invasion, and when operating by invitation of a State. Since there is an interdependence between the LOAC and international human rights law, a State’s agent member of its armed forces must abide by the provisions set by international instruments, such as the Covenant, and apply non-derogable human rights at all times, subject only to the specialised law that is the LOAC. It is a general principle of law that the specialised law will take precedence over the general law, but that otherwise the general law continues to apply. Therefore, the right to life cannot be arbitrarily denied to an individual by an agent of a state under international human rights law, unless superseded by a specialised law. The LOAC permits this, but only under the constraints of its over-arching principle of humanity.

If a final doubt existed as to the application of human rights during armed conflicts, one only needs to read the International Court of Justice decision in its Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 45 to which such recognition is fully adhered. Furthermore, applications of the concepts of human rights law are recognised through international criminal law. Canada has accepted the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court and that of the Rome Statute, and rendered opposable to its agents by means of the Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes Act46. For Canada, the Act recognises three types of crimes under international law for which its agents might be prosecuted: genocide; crime against humanity; and war crimes.

The final element that allows for the interaction of the LOAC with international human rights law is the LOAC itself. Through the Marten’s Clause in the Hague Convention of 1899, which was slightly modified in the Hague Convention of 1907, and reprised in another modified form in the Geneva Conventions of 1949, it states: “Parties to the conflict shall remain bound to fulfil by virtue of the principles of the law of nations, as they result from the usages established among civilized peoples, from the laws of humanity and the dictates of the public conscience.” While there remains a debate as to whether this is to be interpreted liberally or restrictively, the statement links the LOAC with the precepts of public conscience – therefore, of morally acceptable conduct. As a result, it is clear that personnel must know the requirement to apply the norms contained in such law. Training pertaining to the LOAC is provided in most armed forces, but very little is said of human rights obligations. Yet, this is important. As explained above, entrance in an operational theatre is, for liberal democracies, most often justified on the very premise that armed forces are sent to stop gross and widespread violations of human rights and to guarantee the future exercise of these very human rights though the establishment and support of a democratic government. In short, the justification is provided on a moral – not solely a legal basis. When carried out within the collective security system, this provides political and legal legitimacy, as well as a moral justification for the use of force and the possibility of arbitrary denial of the right to life, and other infringements of physical integrity and of personal or public property, in accordance with applicable legal norms under the LOAC.

For military members to comprehend their obligations under international human rights law is to comprehend something more: the moral justification for their deployment in the first place. This creates the moral context framing the thinking of deployed personnel, and it represents a framework for the mission. Instead of a political statement issued stating the political goal of the use of armed forces, it becomes the moral and legal basis upon which their role in the deployment rests. This, in turn, ensures the alignment of the moral and legal goals in all actions and decisions taken on the ground. Framed in this perspective, international human rights law becomes the overall frame of operations, and the LOAC the operative legal basis within the bounds of which armed forces are to conduct themselves in the attainment of the larger objective of guaranteeing the exercise of human rights. This provides the moral guidance under which all operations are conducted.

Grossman book cover On Killing

If decisions made in operations contradict the stated aim of bringing a larger enjoyment of human rights, or if the methods proposed to bring this enjoyment contradict human rights, the stated political goal is dissonant with public conscience and/or the decisions taken in the attainment of these goals are dissonant with the public conscience. The link between this understanding and unethical behaviour cannot be overstated. If a conflict is framed in a manner that does not include human rights, the thought process of military planners will also be framed through another prism that will influence decisions with diminished consideration for the norms applicable to conduct, and may lead to unethical conduct.

Grossman book cover On Combat

The Importance of the Ethical climate and its Setting by Those with Vested Authority

The reasons why acts of unnecessary violence are committed in an armed conflict are more or less broadly understood. Some reasons are general in nature. David Grossman, in his books, On Killing, and On Combat, claims that one percent to two percent of society’s members are sociopaths or psychopaths of varying degrees. It stands to reason that some may be drawn toward the military. Yet, soldiers are not permitted to stray from a unit’s mission and go on a personal rampage. We can deduce that authority and discipline work to constrain such tendencies.

But authority does not prevail at all times. Yale’s Milgram Experiments have clearly shown the propensity of persons put in position of authority to become brutal even without the influence of outside pressures, apart from boredom - even in a fictional context.47 And sub-culture can be a factor. Some psychologists contend that humans are ‘herd animals;’ that in groups, the individual “… is submerged in group acts” in which they have little investment, creating a ‘group mind.’ In plain language, peer pressure is intense.48 In the case of ‘specialist units,’ it is argued that “… externally directed aggressive behaviour, which enjoyed a maximum of group approval, tended to relieve the individual of any feeling of vulnerability.”49

The issue, then, resides in knowing what preventative measures can be implemented.

This can be couched in theoretical terms: for example utilitarianism, focused upon achieving good consequences from a conflict; or by adopting the deontological approach of Kant, by which it is one’s individual duty to ensure ethical conduct in an armed conflict.50

But there is a more practical method, namely, the instillation of the highest moral standards and indoctrination through applied ethics. In Canada, this is the approach taken, adopting a values-based programme of indoctrination. This correlates with proposed theories, such as that of Jim Frederick in his book, Black Hearts, and to the four factors leading to unethical conduct, as subscribed to by Brigadier-General H.R. McMaster51: namely, ignorance, uncertainty, fear, and combat trauma. The premise that the environment influences the risk of unethical conduct is subscribed to by both authors, and it is also the belief of this author that together they form a large portion of the factors contributing to a permissible context. To inoculate soldiers against potential unethical conduct, McMaster proposes a concerted effort in four areas: applied ethics or values-based instructions; training that replicates as closely as possible situations that soldiers are likely to encounter; education with respect to the culture and historical experience of the people among whom a conflict is being waged; and, lastly; leadership that strives to set the example, to keep soldiers informed, and to manage combat stress.52

There is no doubt that training will help reduce fear and combat trauma, while education will address ignorance. However, uncertainty is not entirely covered, in and of itself. Certainly, keeping soldiers informed reduces uncertainty. And yet, it is perhaps not only the uncertainty in the conflict that is so much at play, but also uncertainty with respect to the reasons of a given mission, and the commitment of personnel that have a part to play.

As the Atlantic Charter and its insertion in the moral and legal continuum framed the conflict it addressed, certainty as to the moral foundations of a conflict has its part to play, and it transcends the concept of humanity found in the Just War tradition. And this humanity is transposed, not only in dealings with the general population and with enemy forces, but also in the humanity required of a state’s own armed forces.

One of the responsibilities of persons vested with authority is to preserve their troops. This includes preserving the individuals forming a given unit; the preservation of their humanity.

As previously written,53 and admittedly without empirical data, there is a contention that whether justified or not under jus ad bellum and jus in bello, the act of killing damages one’s humanity.54 In order to protect against this, it is the responsibility of leaders to act in a manner that guides personnel, even in the most dire situations, taking a proactive stance, and enacting orders that acknowledge the context in which they must act, and that clearly state the constraints imposed by a values-based ethical system.

It is not a coincidence that many unethical acts during operations were committed because orders were unclear. It is the imprecision of commands issued that frequently resulted in unethical actions at the tactical level that undermined the strategic objectives of a mission.55 Therefore, above all else, the primary element that must be in place to prevent unethical behaviour is to create the proper ethical climate. A leader in command will show commitment to the ethics of waging warfare within a framework of reference that will truly circumscribe the operations he or she commands in terms of its effects upon supporting and enabling the exercise of human rights, fully respecting the legal obligations of the LOAC but further reinforcing the applicability of its jus ad bellum and jus in bello principles, and thereby protecting his or her subordinate’s humanity. He or she will demonstrate fortitude and courage, even in the most difficult situations, to enforce the values for which the armed forces are committed to the fight, thereby preserving the mission and preserving the personnel deployed. By doing this, such a leader will have created and will maintain the ethical command climate that will guide the mission.

DND photo IS 2011-1013-20

A soldier hands food to Afghan children

Conclusion

This article is solely a proposal to reframe legal-ethical thinking when looking at applied ethics in operations, and in regard of the applicable body of law as a framework that must be coherent with its primary objective and its means of implementation. It has also intended to propose a method by which to achieve this implementation through the existing international legal system, including the collective security system, the LOAC and international human rights.

An incoherent mission contradicting this aim will create uncertainty and a faulty ethical command climate, wherein mission success means acquiring a piece of ground or destroying enemy forces, but does not met the concerns of the political and strategic aims of the use of force.

Such a faulty ethical climate creates a permissible context. Embarking upon such a flawed-structure mission will not only leave a state with armed forces diminished through casualties, but will destroy the very humanity which its armed forces are supposed to protect and help enforce. In such interventions, the best one can expect is an “… honourable end to hostilities;” a signature phrasing that usually means failure to attain mission success.

DND photo IS 2011-1017-05. Photo by Sergeant Matthew McGregor

A Commander introduces himself to men from a local village in Panjwa'i District

Even when there is convergence between the framing of the goals and the values underlying them, the means of implementation of these goals must respect the LOAC, in a larger form, as accepted by the public conscience. The means must be aligned with the goals, and must therefore respect our values within the confines of the proper ethical command climate.

Whether at home or abroad, uniformed citizens are vested with great responsibility through the devolution of trust by their government and their fellow citizens. Their values, as indoctrinated to reflect those of our society, must be their first guidance, and it must be reflected in their application of legal norms.

NOTES

- National Defence Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. N-5. at Article 14.

- Ibid. at Article 18.

- Even under the Emergencies Act, R.S. C. 1985, c. 22 (4th Supplement).

- See A. English, Professionalism and the Military - Past, Present, and Future: A Canadian Perspective, paper prepared for the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, May 2002, accessed 4 March 2011 at: <http://www.cfc.forces.gc.ca/JCSPDL/Readings/21_e.pdf> confronting the notions of Huntington, Jarowitz, and Abrahamson with the historical development of professions and the changing nature of the sociological concepts of the military profession.

- Duty with Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada, (Kingston, ON: Canadian Defence Academy, 2009), p. 10.

- S. Fitch, “Military Professionalism, National Security and Democracy: Lessons from the Latin American Experience,” in Pacific Focus, Vol. IV, No. 2 (Fall 1989), p. 101.

- Duty with Honour, Note 5, at p. 34.

- Ibid.

- National Defence Act, Note 1, at Article 3.

- Public Service Employment Act, R.S.C 2003, c. 22, ss., pp. 12-13.

- Values and Ethics Code for the Public Service, at: <http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pubs_pol/hrpubs/tb_851/vec-cve-eng.asp>, accessed 25 January 2011.

- The three ethical principles are: respect the dignity of all persons; serve Canada before self; and obey and support lawful authority. Its six ethical obligations are: Integrity, Loyalty, Courage, Honesty, Fairness and Responsibility. Available at; < http://www.dep-ped.forces.gc.ca/dep-ped/about-ausujet/stmt-enc-eng.aspx>, accessed 25 January 2011.

- P. Kasurak, “Civilianization and the Military Ethos: Civil-military Relations in Canada,” in Canadian Public Administration, 25.1 (1982), p. 108.

- Ibid.

- G. Huackabee, “The Politicizing of Military Law- Fruit of the Poisonous Tree,” in Gonzalez Law Review 45 (2009-2010), p. 611, citing Stephen M.R Covey, The Speed of Trust, 2006, p. 30.

- Christianne Tipping, “Understanding the Military Covenant,” in The RUSI Journal, 153. 3 (2011), pp. 12-15 at p. 12.

- Ibid.

- Duty with Honour, Note 5, p. 44.

- Giampiero Giacomello, “In Harm’s Way: Why and When a Modern Democracy Risks the Lives of Its Uniformed Citizens,” in European Security, 16. 2 (2007), pp. 163-182.

- H. McCartney, “The Military Covenant and the Civil–military Contract in Britain,” in International Affairs 86: 2 (2010), pp. 411–428 at p. 411.

- Ibid. at p. 421, citing Hew Strachan, “Liberalism and conscription: 1789–1919,” in Hew Strachan, (ed.), The British Army: Manpower and Society into the Twenty-first Century ( London: Frank Cass, 2000), p. 13.

- Ibid. at p. 414, citing Lawrence Freedman, The Transformation of Strategic Affairs (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2006), p. 41.

- Ibid., p. 419.

- Ibid., citing Christopher Dandeker, “Recruiting the All-Volunteer Force: Continuity and Change in the British Army, 1963–2008,” in Stuart A. Cohen, (ed.), The New Citizen Armies: Israel’s Armed Forces in Comparative Perspective (London: Routledge, forthcoming 2010).

- Erakovich, "A Normative Approach to Ethics Training in Central and Eastern Europe", International Journal of Public Administration 29, (2006): 1229–1257 at 1231.

- Reed R. Bonadonna, “Doing Military Ethics with War Literature,” in Journal of Military Ethics, 7: 3 (2008), pp. 231- 242, at p. 231.

- Sara Mackmin, “Why Do Professional Soldiers Commit Acts of Personal Violence that Contravene the Law of Armed Conflict?”, in Defence Studies, 7.1 (2007), pp. 65–89, at p. 66.

- Martin L. Cook and Henrik Syse, “What Should We Mean by 'Military Ethics’?”, in Journal of Military Ethics, 9.2 (2010), pp. 119-122, at p. 119.

- Michael J. Broyde, “Battlefield Ethics in the Jewish Tradition,” in American Society International Law Proceedings 95, (2001), pp. 82-99 at p. 94 and p. 95, comparing the Bible to the Sifri, one of the oldest of the midrashic source books of Jewish law.

- Ibid., at p. 93.

- Jeff McMahan, “The Ethics of Killing in War,” in Ethics 114 (2004), pp. 693–733, at p. 714.

- T. Ruys, “Licence to Kill? State-Sponsored Assassination under International Law,” in Military Law & Law War Review 13 (2005), pp. 1-50, at p. 23.

- Elizabeth Borgwartz, “When You State a Moral Principle, You Are Stuck With It,” in Virginia Journal of International Law 46 (2005-2006), pp. 501-562, atp. 517.

- The Atlantic Charter, 14 August 1941.

- Solon Solomon, “Targeted Killings and the Soldier’s Right to Life,” in International Law Student Association Journal of International & Comparative Law (2007), pp. 99-120 at 105-106.

- Borgwartz, Note 33, at p. 506.

- McMahan, Note 31, at p. 695.

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 19 December 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, Can. T.S. 1976 No. 47, 6 I.L.M. 368, entered into force 23 March 1976, accession by Canada 19 May 1976, at Article 6, especially 6(2).

- Solomon, Note37, p. 104.

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 19 December 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, Can. T.S. 1976 No. 47, 6 I.L.M. 368, at Article 2.

- “Reply of the Government of the United States of America to the Report of the Five UNHCR Special Rapporteurs on Detainees in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba,” in International Legal Material 45 (2006), pp. 742-767, at p. 743.

- See Louis-Philippe F. Rouillard, “Misinterpreting the Prohibition of Torture under International Law: The Office of Legal Counsel Memorandum,” in AmericanUniversity International Law Review, 21 1 (2005), pp. 9-42.

- Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 31 (2004), CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13, Para. 10, and the International Court of Justice, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 2004 (9 July 2004).

- Commission on Human Rights, Situation of Detainees at Guantánamo Bay, E/CN.4/2006/120, 27 February 2006, Sixty-second Session, Items 10 and 11 of the provisional agenda, at p. 6, Para 11.

- Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 31 (2004), CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13, para. 10 and the International Court of Justice, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 2004 (9 July 2004).

- Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes Act, R.S.C. 2000, c. 24.

- S. Mackmin, Note 27, p. 81.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- H.R. McMaster, “Remaining True to Our Values - Reflections on Military Ethics in Trying Times,” in Journal of Military Ethics 9.3, (2010), pp. 183-194, at p. 187and p. 188.

- Ibid., at pp. 187-188: ignorance, uncertainty, fear, and combat trauma.

- Ibid., at p. 188.

- Rouillard, Note 44 at Chapter 13.

- S. French, “Sergeant Davis's Stern Charge: The Obligation of Officers to Preserve the Humanity of Their Troops,” in Journal of Military Ethics 8.2 (2009), pp. 116-126 at p. p. 118.

- McMaster, Note 52 at p. 189.

DND photo AR2011-0504-021 by Master Cor poral Dan Shouinard

CO Health Services Unit (HSU) (left) greets the DComd Kandahar Regional Medical Hospital (KRMH), at CAMP HERO