SUPPORT SERVICES

CWM 19710261-0448.

Horses and Chargers of Various Units, by Sir Alfred James Munnings, 1 January 1918.

The Case for Reactivating the Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps (RCAVC)1

by Andrew G. Morrison

Major Andrew G. Morrison, BSc, MVB, CD, is an Army Reserve Intelligence officer currently serving as the Commanding Officer of 725 (Glace Bay) Communication Squadron. He is also an associate veterinarian at Sunnyview Animal Care Centre in Bedford, Nova Scotia.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Up until the end of the First World War, horses and other animals were a common sight on the battlefield, either as chariots of war, or as the backbone of the supply train. By the late-19th and early 20th Centuries, national armed forces (including that of Canada) had added veterinary services to their order of battle in order to ensure these vital animals were protected from disease and treated for injury. But with the advent of mechanised warfare, the majority of service horses were retired - and in some cases (including Canada), the supporting veterinary corps were disbanded. However, as the decades passed, modern warfare changed yet again, with great armour battles based in Europe and Africa becoming far less a feature of combat. At present, 21st Century warfare places a much greater focus upon counter-insurgency campaigns in which the military is not fighting through the objective, but is living with it. The complexity of operations in which insurgents are engaged, not on battlefields, but within living, working societies, requires the development of new tools, as well as the return of some old tools. This article will argue that the use of the modern military veterinarian, whose efforts are focused upon building sustainable agriculture in order to stabilize societies through better public nutrition and increased opportunities for trade, is one such tool that should again be employed by the Canadian Forces.

CWM 19920085-903.

Troops of the Canadian Light Horse advancing from Vimy Ridge, 9 April 1917.

Brief History of the Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps

Prior to 1910, veterinary support to the military forces in Canada was provided by a regimental system. Local veterinary practitioners would hold a commission in a mounted unit, and would leave practice for 10-15 days per year to train with and supervise the regiment’s horses. Only one or two regiments had permanent veterinary officers.2

In 1910, there began a gradual move to replace the Regimental Veterinary Service with the Canadian Army Veterinary Service, which included the Canadian Permanent Army Veterinary Corps (the regulars), and the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps (the reservists).3 By the start of the First World War, this reorganisation had not yet been completed, but sections from Winnipeg and Montréal were sufficiently developed to form the backbone of the Canadian expeditionary veterinary services, referred to as the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps – Canadian Expeditionary Force (CAVC-CEF). During the initial move to England in October 1914, the CAVC supervised the shipping of 7636 horses in 14 ships, with the SS Montezuma carrying the largest number, 973 animals. During the crossing, only 86 horses (less than one percent) were lost.4

In time, two veterinary hospitals were set up in Europe: No. 1 Canadian Veterinary Hospital in Le Havre, France, and No. 2 Canadian Veterinary Hospital in Shornecliffe, England. The latter eventually housed the Canadian Veterinary School and the Instructional School for Farriers. No. 1 Canadian Veterinary Hospital was one of eighteen Imperial Veterinary Hospitals established on the lines of communication, and it supported, not just Canadian equines, but all horses of the Imperial Army.5 At its peak, No. 1 Canadian Veterinary Hospital had stabling for 1364 horses, although at one point, the number of horses under care exceeded 2000.6

In addition to the hospitals, veterinary support extended to the field forces, where 221 officers and sergeants cared for the 23,484 horses of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, as well as other horses of the Imperial forces. Their role was not only to treat minor illnesses, but also to provide supervision and preventative measures to ensure the fitness of the fighting horses. More serious cases were transferred to the veterinary hospitals, and replacements were provided through the remount units. Mobile veterinary sections provided additional services and a link to the veterinary hospitals.7

At this formative time in its history, the role of the veterinary service as a whole was to reduce animal wastage. During the entire war, the Canadian gross wastage rate (including animals evacuated to hospital, missing, and dead) was 26 percent, where the dead wastage was 9.5 percent. During the war, the Canadian Corps returned 80 percent of injured horses back to the line, where they continued to move soldiers, ammunition, food, water, guns, and so on, into combat.8 In November 1919, the CAVC received the Royal designation, in honour and recognition of its excellent performance during the war, a title that was later extended to the CAVC in 1936.9

The interwar years brought about the mechanization of the Canadian Army, as well as reorganization and rationalization. The result was a smaller RCAVC, whose role was accordingly diminished like that of other units. However, the twilight years of the Corps were characterised by a leadership (including that of the RCAVC itself) which did not foresee a role for the veterinary corps beyond the welfare of the military horse. As a result, on 1 November 1940 the RCAVC was disbanded by a recommendation of the Treasury Board, which was approved by the then-Governor-General, the Earl of Athlone. The annual cost savings achieved was just $10,334.10 The demise of the Corps was lamented by contemporaries in editorials appearing in The Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science;11 in one such editorial, the decision-makers were characterised as suffering from “muddle-headedness.”12

CWM 19710261-0457

Fort Garry's on the March by Sir Alfred James Munnings, 1 January 1918.

The Modern Military Veterinarian

If military veterinarians are no longer looking after the health and welfare of the Regimental horse, then what is their role in modern warfare? The US Army Field Manual 4-02.18, Veterinary Service Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs), specifies three broad functions for the military veterinarian:

- food safety, food security, and quality assurance;

- veterinary medical care; and

- veterinary preventive medicine.13

These three functions are also the core of civilian veterinary medicine. The first function, that of food safety, food security, and quality assurance, does not have much of a public profile, but, in fact, Canada’s food supply is secured and monitored in large part by veterinarians (meat inspectors being the best-known example). Anyone with pets would be familiar with the second function, that of veterinary medical care. The third function, veterinary preventative medicine, prevents disease in animal populations (i.e., via vaccination, proper nutrition, effective breeding, etc.), but is also an important part of the human medical system that identifies and helps prevent transmission of ‘zoonoses’ (diseases that pass from animals to humans).14

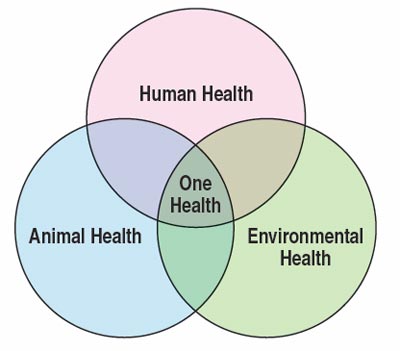

All these veterinary functions also constitute a vital contribution to the “One Health” concept - an emerging field of study which connects veterinary, human and environmental health into a comprehensive, synergistic approach to planetary health. One Health promotes the tenet that the environmental, medical, and veterinary health disciplines must be linked in order to provide a solid foundation for progress.

17 Wing Publishing

Circles of health

It is “…a movement to forge co-equal, all-inclusive collaborations between physicians, veterinarians, and other scientific-health and environmentally-related disciplines,”15 and is supported by government agencies and professional associations worldwide.

The modern military veterinarian can employ the above three functions in support of three broad military roles:

- support to conventionally-deployed forces;

- support to civil authorities; and

- support to operations other than war.

The first role, support to conventionally-deployed forces, can be executed by providing care to military working dogs and other military animals, support to the military medical system by providing veterinary medical intelligence on the ‘zoonoses’ of a particular area of operations, and advice and support to commanders on the safety of local food procurement. Training can be provided to soldiers with respect to safe practices around indigenous animals. This role is largely part of medical care and force protection.

The second role, support to civil authorities, directly reinforces provincial and federal veterinarians during an emergency. This can be done by operating in regions and conditions where civilian veterinarians cannot, as well as advising commanders during domestic operations that involve livestock (such as rafting of cattle in the New Brunswick floods of May 2008 by CF Engineers)16 [see Figure 2], and assisting authorities during the 2001 outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease in the United Kingdom). Although animal care and welfare may seem unnecessary to military planners, it must be acknowledged that the evacuation of civilians from an area of operations is more easily accomplished if provisions have been made for the care and transport of their animals (whether pets or livestock). For instance, it has been informally estimated that as a result of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, up to 50 percent of the human fatalities could be attributed to people refusing to evacuate without their pets, or returning to the disaster zone in an attempt to rescue their pets.17 A Zogby International poll found that 61 percent of pet owners would refuse to evacuate their homes if they could not take their pets.18 Given that about 56 percent of households in Canada contain at least one cat or dog, that there are an estimated 8.5 million cats and 6 million dogs in Canadian households,19 and that many pets are considered part of the family (even to the point of being regarded as “furry kids”), the human emotions involved can be intense, and therefore should be a factor in planning for domestic operations.

CP photo 7855775 by Andrew Vaughan

Military personnel and local farmers/veterinarians escort cattle across the flood-swollen St. John River, 2 May 2008.

The third role, support to operations other than war, is perhaps the most relevant for Canada, given that Canadian Forces are, and likely will continue to be, deployed to disaster zones (such as Haiti) or to developing, “failed/failing states” (such as Afghanistan, Congo, and Sudan). Canadian Army Counter-Insurgency Operations recognizes that the military may be the only element of power capable of working in such environments.20 The root of much civil strife, though framed in ideological arguments, is generally linked to quality of life. Issues like lack of food, disease, and a poor economy are often the result of agricultural failure. By improving the state of livestock health through emergency, routine, and preventative medicine, and by improving livestock hygiene, the modern military veterinarian can assist in improving food production and in reducing animal and human disease, thereby establishing a base from which to improve the economy through increases in local market activity. When working with non-governmental organisations and government agencies such as the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), separate areas of operations would usually be defined. CIDA would not normally contemplate directly-supported or joint projects with the military. Rather, the likely modus operandi would see the military on the ground first, providing veterinary services during the stabilization period. Later, CIDA could, through their programs, replace and expand upon the military veterinarians’ initial work. The military could provide reconnaissance data to CIDA and ensure a smooth handover.21

All three of the above military roles can be supported by one or more types of military veterinary tasks, as outlined below.

UN Photo by Indian photographer.

UN forces from India assisting a camel in the Sudan.

The Role of Modern Military Veterinarians amongst Canada’s Allies and Other Armed Forces

Given that, historically, the military veterinarian was closely tied to the horse, and that in Canada, the move towards adopting the ‘Iron Horse’ led, in part, to the disbandment of the RCAVC, it is not surprising that similar moves were afoot amongst Canada’s allies and other militaries during the mid-20th Century. Australia and New Zealand disbanded their veterinary corps in 194622 and 194723 respectively.

However, many other armed forces still have active veterinary services, both Regular and Reserve components. Currently, notable allied services include the United States Army Veterinary Corps,24 and the Royal Army Veterinary Corps (UK).25 The 55th International Military Veterinary Medical Symposium, held in 2009 in Marseilles, France, saw the participation of military veterinarians from Austria, Croatia, Slovenia, Morocco, Denmark, the Netherlands, the United States, France, Italy, Germany, Poland, Belgium, Norway, and Finland.26 The 19th annual Asia-Pacific Military Medical Conference held in 2009 in Seoul, South Korea, had a total of 36 military veterinarians participating from Malaysia, Nepal, the Philippines, South Korea, and the United States.27 The United States,28,29 German30, and British31 armies have had veterinary services in Afghanistan, where both the US32 and the UK33 have had members of their veterinary services killed in action. Both International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and NATO have used veterinary programmes in Afghanistan.34,35 Civilian veterinary programs have also started in some parts of Afghanistan.36,37 The Indian Army has had veterinary detachments in the Sudan38 where they worked with Canadian Civil Military Cooperation (CIMIC) Officers.Clearly, in all these cases, the modern military veterinarian has found varied and valuable work to undertake, as these armies do not rely upon the horse.

DSC 0068 Indian Army photographer.

Indian Army veterinarians administering aid to a cow.

How Could Canada Use the Military Veterinarian?

Development/Force Protection

Perhaps the greatest value of military veterinarians is their second-order effect of force protection, derived from the first-order effect of development work. Very basic veterinary projects, such as parasite removal, vaccination, improved nutrition, and better breeding can significantly improve animal production among a given local populace. Increased productivity yields more food, better human health, more economic activity, and, ultimately, a greater number of local citizens who experience higher levels of happiness, satisfaction, and perhaps even gratitude. Insurgents are not likely to provide a veterinary service to the community. Therefore, in an insurgency, the military veterinarian provides an essential service that the locals are unlikely to jeopardize. This has the potential to lead to better intelligence, fewer Tier II fighters, and a more stable community that sees value in the military presence. The insurgency then appears unable to look after the needs of the locals, and it loses legitimacy. At a more advanced level, veterinary involvement in Agri-business Development Teams (ADTs)39 can assist in stabilizing and growing the agricultural economic base of society, aiding the supported community to increase its capacity to meet its most basic of psychological needs. Once the security situation has improved, in part due to veterinary activities, the greater civilian veterinary resources of governmental and non-governmental organisations can continue to build upon the foundations established by the military veterinarian.

As a partner in global animal health and security, the military veterinarian also has a role to play in keeping foreign disease out of Canada. Work done overseas in identifying foreign disease, and in the implementation of appropriate decontamination or quarantine procedures, can assist the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in preventing foreign disease outbreaks in Canada that would jeopardize the food upon which our health and economy depends.

Domestic Operations

The potential scope of Canadian military veterinarians in Domestic Operations is vast. The most likely scenario would involve aid to civil powers in response to a natural or man-made disaster. Every disaster will have an animal component, whether pets, livestock, or wildlife. The military veterinarian would be a valued resource in these operations, providing liaison with other government departments on animal issues, and providing service on the ground where civilian resources are unable to operate, or have been exhausted.

The Canadian Veterinary Medical Association has recently established the Canadian Veterinary Reserve (CVR) as a civilian tool for emergencies.40 Initially, the CVR was formed to give the Canadian Food Inspection Agency a surge capacity in the face of a foreign animal disease outbreak on Canadian soil. It has subsequently expanded to a point where it can provide individual and small veterinary team support, both domestically and abroad. Currently, this support is voluntary and it provides only the services of veterinarians, without any equipment. A military veterinary capability could support and even serve as the vanguard for the CVR, due to its faster deployability and to the greater acceptable risk assumed by military personnel. A military veterinary capability would also have its own equipment and could access greater resources through the military supply system. In the case of a Domestic Operation where the military is supporting an evacuation (i.e., floods), military veterinarians can be deployed into the evacuation area to care for and rescue pets and livestock prior to transfer to civilian authorities.

Many animal rescue organisations now provide mobile shelters to assist with disasters, but their access to the disaster area may be restricted for security and mobility reasons. Anecdotally, it has been suggested that there have been instances in which civilian organizations attempting to rescue animals have been mistaken for looters.41 The military veterinarian can serve as the bridge between these civilian organizations that provide the majority of care, and the secured area of operations. The animal rescue world is a highly complex environment incorporating legally mandated SPCAs and humane societies, charitable organisations, emergency measures organisations, well-meaning individuals, and so on; military officers unfamiliar with this world would find it difficult to integrate effectively with these groups. A military veterinarian would be expected to have some mastery of the complexities surrounding animal issues and the associated agencies, including government departments, official and unofficial non-governmental organisations, and well-meaning but sometimes misguided individuals. The military veterinarian could play a valuable role as a commander’s liaison with this dynamic and often emotional environment.

Arctic Sovereignty

Currently, very few veterinarians work in remote parts of Canada, especially the North. Army veterinarians could use these regions for training exercises, achieving realistic training by running triage facilities and quick impact projects (i.e. vaccine clinics) while providing service to currently under-serviced communities. Adding veterinarians to Arctic sovereignty missions would add extra legitimacy to Canada’s presence and additional services to its citizens in the North. A recent exercise, Operation Nunalivut 10, worked with the Danish forces’ SIRIUS Dog Sledge team. The team was there to conduct a familiarization patrol around CFS Alert.42 With a force of military veterinarians, the Canadian Forces might, in future, consider the use of service dog teams in the North, in conjunction with the snowmobiles and ATVs currently used by Rangers and other forces.

Research

Although this would admittedly be beyond the likely scope of the Canadian Forces, military veterinarians can serve as important partners in military research. Research into biological defence - a component of Chemical, Biological, Radiological-Nuclear, and Explosives (CBRNE) - can be directly supported by military veterinarians, as many biological agents are of animal origin (i.e. anthrax).43 The US Navy Marine Mammal program not only trains marine mammals for service, but conducts important research with respect to their health, as well as methods of protecting them from the effects of military equipment.44

Service Animals

Several federal government departments have active working dog programs, including the RCMP Police Dog Service and the Customs and Border Services Agency, whose dogs detect narcotics, firearms, currency, and agricultural products. The Canadian Forces also has working animals, including the Military Police Working Dog Trial.45 In both Bosnia and Afghanistan, pack mules and donkeys have been used by the CF where access by vehicles was difficult.

CP 4610561 by James McCarten

Canadian soldier Corporal Scott King returns from grazing Hughes, the two-year-old donkey pet of Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan, 2 April 2008.

Goats have been used by CIMIC teams in Afghanistan as reparation for damage and injury caused by CF actions. The CF contracts civilian companies46,47,48, to provide explosive detection dogs in Afghanistan,49 which led to a Safety Digest notice after a soldier was bitten.50

DND photo AR2007-B076-0020 by Corporal Pop.

CIMIC operator Captain Kent MacRae, a reservist with the Prince Edward Island Regiment, escorts a goat to an Afghan family.

The Bottom Line

To deny the intensity of human emotion where animals are concerned, because the object of the emotion is an animal rather than another person, is both naïve and unrealistic. Not having a plan to cope with the animals located in an area of operations can make it more difficult than necessary to assist the local populace. There are also situations in which only military or specially-trained veterinarians could operate, such as security and CBRNE environments. Decontamination of animals is likely to be necessary when civilians are being decontaminated. Veterinary expertise could be useful for the biological portion of CBRNE, given that many of the agents involved are of animal origin.

In these operations, civilian veterinary involvement must, of necessity, be limited, especially in the initial phases of disaster operations, and over the longer term in areas with security problems. A military veterinarian can be part of reconnaissance teams and the Canadian Forces’ Disaster Assistance Relief Team (DART), and can undertake regular rotations through theatres of operation.

Some military responsibilities in these areas would include gaining support of the local population for the mission, mitigating some of the root economic causes of the conflict, and enhancing domestic services, such as water and food supplies. The military veterinarian provides a bridge until the security situation permits civilian veterinarians to resume or establish their practice.

By working with the communities within an area of operations, providing basic training for local veterinarians and farmers, and facilitating the delivery of supplies such as vaccinations and de-worming products, the military veterinarian can start programs aimed at the well-being of agricultural livestock that will increase the productivity of local herds and flocks. The improvement in overall conditions of the people and through them, the society itself, can assist the military commander in shortening the period between the commencement of military operations and the handover of a secure area of operations to civilian authorities. Many of the projects spearheaded by military veterinarians can be relatively inexpensive and short-term, but can also provide lasting benefits, even after the operational forces depart. Handover to reputable NGOs or agencies, such as CIDA, would bolster long-term sustainability.

The Reactivation of the RCAVC: What Would It Look Like?

A reactivated Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps, structured within the Army Reserve, would not have to be a large or expensive program. It could be completely ‘scalable’ to available resources, giving flexibility to changing operational environments. The foundation of the Corps would be established veterinarians and registered veterinary technicians (RVTs) subsequently trained as Army Reserve soldiers. Recruiting would be restricted to those already qualified and licensed in a province of Canada. Both these professions have training, certification, and regulatory systems in place. The training bill would be limited to basic soldier skills and the professional ‘delta’ between the civilian and military veterinarian. This could be contracted to our allies’ existing programs, as well as domestic programs from other government departments (i.e., Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and Department of Agriculture courses) and Emergency Measures Organisations. CFIA already runs a foreign disease course, and is involved with the CVR in developing the all-hazards training piloted in Ottawa in March 2010.

Establishing the RCAVC within the Army Reserve would be beneficial for many reasons. The veterinarians’ clinical and surgical skills could be maintained through private practice, eliminating the need for hospital infrastructure. Veterinarians and registered veterinary technicians would maintain their provincial licenses through mandated continuation training, reducing the training bill. In return, the military could provide compensation through pay and benefits, which would be cheaper than designing, building, and delivering the training itself. As noted earlier, several of Canada’s allies already possess strong veterinary corps. Their training programs, doctrine, and TTPs could be adapted to Canadian needs.

The number of veterinarians and RVTs needed would be a function of government and military policy. As this topic has not been the subject of discussion for some time, there is no formal policy to which reference can currently be made. For the sake of this discussion, the Army’s Managed Readiness Plan (MRP)51 could be used as the basis of the planning assumptions. For example, the MRP calls for up to two Army Task Forces to be deployed at any one time. The minimum veterinary capability would be a veterinary detachment: one veterinarian and two RVTs. Using a five-to-one ratio for force generation, one Task Force could be sustained with six veterinarians and twelve RVTs. Thus, with two Task Forces in the MRP, the RCAVC would need a minimum establishment of twelve veterinarians and twenty-four RVTs. This is a relatively modest structure compared to the current US Army Veterinary Corps of 2700 members.52

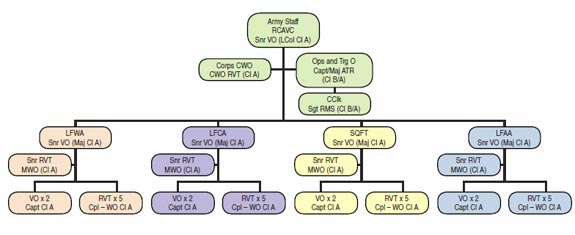

17 Wing Publishing Winnipeg.

RCVAC Organization Chart

Given that the Army is divided into four Land Force Areas, the 36 positions previously identified could be organized into four veterinary sections of three veterinarians and six RVTs each, one for each Land Force Area Headquarters. Support would come from within the LFA Headquarters. The sections could be organised under an Area Veterinary Officer, or as part of the Area Surgeon Branch. If the role is to be limited to humanitarian missions, the veterinary section could be housed in the Area G9 (Influence Activities) branch.

A small Corps Headquarters consisting of a Senior Veterinary Officer (Corps Commander), a Senior RVT (Corps Sergeant Major), an operations and training officer, and a clerk would complete the unit of 40 soldiers. The operations and training officer and the clerk should be full-time positions.

From this small unit, the Canadian Forces would gain the capability to better support the Government of Canada’s objectives across the country and around the world, through the advancement of animal health in some of the most needy and insecure areas of the globe, in addition to adding another level of protection around the soldier.

Alternatively, veterinary capability could be based within the Canadian Forces Health Service, but the structure should be similar, possibly organized around the JTF surgeons. Given that veterinarians are primarily deployed to land operations, all veterinarians and RVTs should wear the Army uniform, maintain Army standards, and be attached to Army formations.

Conclusion

The notion that the military veterinarian became obsolete with the service horse is erroneous. Militaries around the globe have retained their military veterinary units, which are currently providing valuable service.53 The Canadian Forces would benefit greatly from a renewed RCAVC, both at home and abroad, supporting combat, development, disaster, and other operations. With the Canadian Forces’ current and future operations to be focused upon failed and failing states - where the foundation of the economies of at least some of these is agriculture - not reinstating the RCAVC might be considered short-sighted. Every conflict involves people, and all civilizations rely upon animals for food, work, and companionship.

The Canadian Forces exists in an era where inter-state conflict is limited, but intra-state conflict is more common. The nature of these conflicts will often call for intervention lasting years or even generations. One cannot effectively repair a failing state without helping to provide the means for that state to feed itself and generate livelihoods for its people. That fact alone justifies the presence of the military veterinarian in modern conflict.

The RCAVC was forged during one of the most brutal wars in history, and acquitted itself admirably. It is time to reactivate the Corps, and provide the opportunity for it to serve once again.

DND

The RCAVC Crest

NOTES

-

Many thanks to Dr. Gordon Dittberner, Prof. Tim Ogilvie, Dr Bill Brown, and all the others who reviewed the drafts of this paper. Also I am grateful to my wife, Dr Jennifer Morawiecki, for her editing.

-

Cecil French, A History of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps in the Great World War 1914-1919 (Guelph: Crest Books, 1999), p. 1.

-

“Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps,” in The Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 5, No. 4(1941), pp. 92-93.

-

“Canadian Army Veterinary Corps,” in The Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science, Vol. 7, No. 10 (1943), p. 290.

-

Headquarters, Department of the Army, FM 4-02.18 Veterinary Service - Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (Washington, 2004), pp. 1-1 and 1-2.

-

Fogelman et al, “The Role of Veterinary Public Health and Preventive Medicine during Mobilization and Deployment,”in Military Preventive Medicine: Mobilization and Deployment, Volume 1 (Washington DC, TMM Publications, 2003),Chapter 30 passim.

-

One Health Initiative will unite human and veterinary medicine. http://www.onehealthinitiative.com (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

140 cows rescued from flood. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/new-brunswick/story/2008/05/03/cow-rescue.html (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Email from Dr Heather Case, American Veterinary Association, 4 May 2010.

-

Emergency plans ensure pets aren’t left behind. http://www.zogby.com/soundbites/ReadClips.cfm?ID=14961 (accessed 16 October 2010).

-

Terri Perrin, “The Business of Urban Animals Survey: The Facts and Statistics on Companion Animals in Canada,” in The Canadian Veterinary Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 48-52.

-

Canada, Department of National Defence, B-GL-323-004/FP-003 Counter-Insurgency Operations (Director of Army Doctrine, 2008-12-13), p. 513, para 2.

-

Personal communication Jean McCardle, Canadian International Development Agency, Feb 2010

-

Ian M. Parsonson, Vets at War: A History of the Australian Army Veterinary Corps 1909-1946 (Canberra: Army History Unit, Department of Defence, 2005), p. 163

-

New Zealand’s Corps badges, 1911 to present. http://www.diggerhistory.info/pages-badges/nz-corps3.htm (accessed 16 October 2010).

-

US Army Veterinary Service. http://www.veterinaryservice.army.mil (accessed 16 October 2010).

-

Royal Army Veterinary Corps. http://www.army.mod.uk/army-medical-services/5320.aspx (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Report of the 55th International Military Veterinary Symposium. http://www.cimm-icmm.org/page/anglais/rapportcongresvetoANG2009.php (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Military veterinarians meet in South Korea, France. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jul09/090715o.asp (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Patricia Rodriguez, “Veterinarian Ryan K. Miller Helps Heal Afghanistan,” in Veterinary Practice News, Vol. 22, No.10, p. 55. <http:www.virtualonlineeditions.com/article/Veterinarian Ryan K. Miller Helps Heal Afghanistan/499524/47170/article.html> (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Army vets wage unconventional campaign abroad. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jun06/060615g_pf.asp (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Marjan, The Lion of Kabul, Afghanistan Kabul Zoo euthanized. http://animom.tripod.com/kabulzoo.html (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Army vet turns ‘Herriot of Helmand.’ http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/DefenceNews/PeopleInDefence/

ArmyVetTurnsherriotOfHelmand.htm (accessed 16 October 2010). -

US Army veterinarian killed in action. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jul06/060715c.asp (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Army dog handler killed in Afghanistan named. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/afghanistan/2461765/Army-dog-handler-killed-in-Afghanistan-named.html (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Afghan veterinarian, civil affairs team helps ranchers. http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=49561 (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

ISAF Provides veterinary care to nomadic tribes. http://www.nato.int/isaf/docu/pressreleases/2008/10-october/pr081031-577.html (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Afghan veterinary association finds its way. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/nov07/071115c_pf.asp (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

US Veterinarians help jump-start Afghan animal health clinic. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/mar06/060315a_pf.asp (accessed 16 October 2010).

-

Center for Army Lessons Learned, “Agribusiness Development Teams in Afghanistan Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures Handbook,” No. 10-10, November 2009. http://uscac.army.mil/cac2/call/docs/10-10/10-10.pdf (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Canadian Veterinary Medical Association and Canadian Food Inspection Agency Establishing Veterinary Reserve. http://www.canadianveterinarians.net/Documents/Resources/Files/508 news-releaseCVR E.pdf (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Personal communication from Dr. Ben Weinberger, a veterinarian who volunteered in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, March 2010.

-

Dog gone it! The Maple Leaf, 28 April 2010, Vol. 13, No. 14, p. 1. http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/commun/mlfe/vol 13/vol13 14/1314 full.pdf (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Veterinarians needed to develop comprehensive animal protection, decontamination plans. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jul05/050701m.asp (accessed 3 January 2012.

-

US Navy’s Marine Mammal Program. http://www.spawar.navy.mil/sandiego/technology/mammals/veterinary.html (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Briefing note for CFD, Military Police Working Dog (MPWD) Trial, Major D.N. Boot, 17 March 2008.

-

Canadian military seeks more bomb-sniffing dogs for Afghan mission. http:///www.capebretonpost.com/Living/World/2010-01-05/article-777188/Canadian-military-seeks-more-bomb-sniffing-dogs-for-Afghan-mission?1 (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Bomb-sniffing dogs a key part of Afghan military team. http://www.canada.com/story print.html?id=2367240&sponsor (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Canadian soldier hurt in bomb blast in Afghanistan. http://www.cbc.ca/world/story/2007/03/20/soldier-injured.html (accessed 3 January 2012).

-

Kelly J. Maguire, VCSi Statement of Capabilities and Experience (rev 1.6), (Las Vegas: Vigilant Canine Services International, n.d.), p. 13.

-

K-9 Canines Aren’t Pets. http://www.vcds-vcemd.forces.gc.ca/dsafeg-dsg/pi/sd-dsg/1-07/article-11-eng.asp. (accessed 16 October 2010).

-

Lieutenant-General J.H.P.M Carron, Managing the Army’s Readiness, 3350-1 (CLS) 25 November 2005, para 5.

-

http://www.veterinaryservice.army.mil (accessed 16 October 2010).

-

Modern media allows a look at these activities. The following links from YouTube demonstrate modern military veterinarians at work. (all accessed 17 October 2010).

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4hknYckzBpo&feature=related - US Army Ethiopian Medical-Veterinary Civic Action Program

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPwkgujJs_A&feature=related - Royal Army Veterinary Corp in Afghanistan - RAVC heroes RAVC explosive detection dog in Afghanistan

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lvByV95dUAo&feature=related - US Army VETCAP in Uganda

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RRE0NGfPWCo&feature=related - US Army VETCAP in Djibouti

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aLfkxP8xVvo - Afghan VETCAP

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sN_NZIkg8uc - Agri-Business Development Team Conducts Training VETCAP