Military History

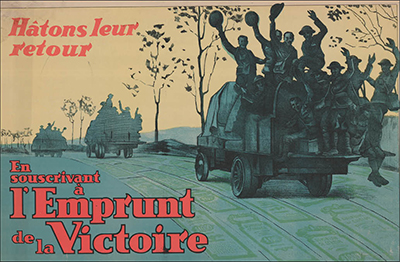

Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-28-590

Recruiting poster

PATRIOTISM AND ALLEGIANCES OF THE 22nd (FRENCH CANADIAN BATTALION, 1914Ė1918

by RaphaŽl Dallaire Ferland

Raphaël Dallaire Ferland is working on his master’s degree in international history at the Institut des hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID) in Geneva, Switzerland. He conducted his research in the Royal 22e Régiment archives in Quebec City under the supervision of Professor Desmond Morton.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

On 27 April 1916, Major Georges P. Vanier, who at the time was in the trenches at St-Éloi with the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion, wrote in his diary: “On my 28th birthday, the newspapers are reporting a revolt in Dublin. Regrettable….” For the Irish, 1916 was the year of the Easter Rising, in which intellectuals encouraged the people to oppose British authority, expressed their fear of conscription, and called for Ireland’s independence. For the 22nd Battalion, 1916 was the year of the Battle of Courcelette. That battle would make the military reputation of the battalion, which was acting “… for the honour of all French Canadians [translation].”1 The nationalisms2 of two peoples who had so much in common would, that year in Europe, take opposite directions: while the Irish rebels were fighting for the right not to go to war as part of the British Empire, the 22nd Battalion was fighting as part of a quest for recognition within that same empire and its colonial army, the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).

This article, which is primarily based on an analysis of war diaries, explores the patriotic sentiment and the allegiances within the 22nd Battalion, the only French-Canadian unit deployed to the front during the First World War. How did the Van Doos (the English nickname for the 22nd Battalion, and later, the Royal 22e Régiment; from the French for 22, “vingt-deux”) feel about their homeland, Canada; their adopted mother country, Britain; their mother country, France; and their French-Canadian nation?

Canada

The town of Saint-Jean, Quebec, was chosen as the training site for the 22nd Battalion in October 1914, but its initial commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Mondelet Gaudet, decided that it was too close to Montreal and the city’s many temptations, so in March 1915, he moved the battalion to Amherst, Nova Scotia.

When they arrived in Amherst, the Van Doos found the streets almost deserted and the shops closed.3 However, that initial coldness between English Canadians and French Canadians did not last. According to Captain Georges Francoeur, it was Amherst’s priest who, hearing of the festive reputation the 22nd Battalion had acquired at Saint-Jean, “… had told the girls and everyone not to come and see the soldiers [translation].”4 Gradually, the Nova Scotians ventured out of their houses and, in the end, all the authors studied praised the hospitality extended by the people of Amherst.5 At the send-off of the Saxonia, which was to take the battalion to England, the mayor delivered a speech praising the French-Canadian soldiers. According to La Presse reporter Claudius Corneloup, “… the city’s brass band played the ‘Marseillaise,’ and our soldiers, touched by that mark of consideration, sang ‘God Save the King.’”6 English Canadians, out of respect, associated French Canadians with France, while French Canadians associated their Anglophone counterparts with the British monarchy. Georges Vanier seems to have been particularly moved by that very Canadian patriotic moment: “The sight was impressive as we drew away to the sound of ‘O Canada’ played by our band. Quietly we left the wharf, the people waving flags, handkerchief [sic] and hats. It was the most ‘living’ moment of our existence so far.”7

Directorate of History and Heritage

Map of Western Front 1914-1918

Once the battalion arrived at the front, wrote Georges Francoeur, there was considerable cooperation between the Van Doos and the rest of the CEF. During an inspection on 2 October, the captain expressed his gratitude for the kind words of the Anglophone 5th Brigade Commander, Brigadier David Watson. Two days later, when the 22nd Battalion relieved the Yorkshire Light Infantry Regiment, “… the officers were as courteous as could be, giving us all the information we needed.”8 All the authors studied offer similar examples of cooperation between French Canadians and English Canadians. Waging war on the same front, where a battalion’s survival depended to some extent upon the rest of its brigade, its division, and its corps, created solidarity between French Canadians and English Canadians.9 The only exception found in this study was a complaint from Major-General R.E.W. Turner, on 21 August 1916, that the Van Doos did not talk much to the 75th (Toronto) Battalion. The problem, which may have been due to the language barrier, was quickly solved after the 22nd’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas-Louis Tremblay, intervened.10 Of course, Tremblay was competitive and was quick to note the blunders of the other battalions,11 but there is nothing to indicate that the same kind of competition did not exist between the Anglophone units, and Tremblay’s zeal can be explained by his awareness that, through his battalion, he was representing an entire ‘race.’ In reality, the friction between divisions (which cooperated less directly than the battalions within the same division) seemed more intense than that between French Canadians and English Canadians. On 23 and 24 June 1916, Tremblay complained about the 1st Division, which had falsely accused the 2nd Division of abandoning the trenches at Mont Sorrel: “Men from the 25th Bn [part of the 2nd Division] have already sent a number of men from the 7th Bn [part of the 1st Division] to the hospital [translation].”

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-002666

Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas-Louis Tremblay

If one can speak of Canadian patriotism among the Van Doos, it mainly took the form of a passive sense of belonging: without exception, the authors examined in this study speak of Canada, not Quebec, as their homeland. Their patriotism was passive in the sense that it rarely motivated them to fight.12 For them, Canada was the land to which they felt attached, where their nostalgia was focused—especially during major holidays. On Christmas Day 1915, Francoeur tried to capture the mood of his platoon: “All of us have left behind in our dear Canada a family we think of often, and on this day we very much wish we could be with them to revive old memories [translation].” Vanier, in a letter to his mother, described a traditional Canadian celebration (“… we sang Canadian songs and ate Canadian dishes”). On New Year’s Day, wrote Francoeur, “… we thought of our beautiful Canada, and we wonder what the New Year has in store for us—a speedy return to our country, or a wooden cross [translation]!”13 He, like all the authors studied, longed to return to his “country,” not to Quebec, where his family was waiting for him.

For French Canadians, Canada represented a dream of comfort, where their ‘near and dear ones’ awaited their return to hearth and home. That dream found expression in the “Ballade des Chaussettes,” a song about socks composed by a French Canadian that, according to Francoeur, was very popular in the trenches:

… Your socks are going to Berlin

We’re taking your Canadian socks

And we know how to wear them

Marching in step, singing “O Canada”

And our blood must go with them … [translation]14

As was considered proper during contacts between citizens of different countries, the Van Doos served as ‘goodwill ambassadors’ in their encounters with Europeans. Some—like Francoeur and his platoon, when they met a Belgian farmer and his two daughters on 10 January 1916—decided to act as ambassadors for Canada: “One was brunette and one was blonde; they spoke French well and we talked for a long time about their country and our Canada [translation].”

Needless to say, all the contributors studied were happy to return to Canada. Arthur J. Lapointe had this to say: “When I woke up this morning, we were nearing Halifax. A soft layer of snow covered the ground all around the city. My heart was bursting with joy as we approached this land that I thought I would never see again [translation].”15

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-000253

Repairing trenches, 22nd Infantry Battalion, July 1916.

Britain

On the other hand, the Van Doos expressed no apparent patriotism or allegiance toward their ‘adopted mother country,’ Britain. Monarchist rhetoric was never used in a motivational speech before a battle, and it seems to have been expressed very rarely in personal diaries. While there might not have been any open hostility toward the Crown, there was no great enthusiasm for it, either. Arthur Lapointe’s indifference upon his arrival in England was typical: “I looked out the window at this country that was unknown to me, but a thick fog cast a melancholy pall over everything before me. What a contrast to our departure from Canada!”16

That feeling of alienation was exacerbated during the soldiers’ ten-day annual leaves. In London, hospitality for the Canadian troops was provided by Protestant organizations where only English was spoken,17 so it is understandable that some of the Van Doos preferred the French capital to the English capital. Some Van Doos also mentioned being constantly watched because it was so unusual for the British to see a Francophone battalion within a colonial army.18 Tremblay tells of how, in Dover, England, he and his brothers-in-arms were stopped, questioned, and followed by British soldiers on motorcycles. In his view: “In Dover, we became suspect because we spoke French.”19

Of all the authors studied, only Vanier—whose mother was Irish and who condemned the Easter Rising—expressed a sense of belonging to Britain. On 5 August 1915, he described Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden’s visit to the East Sandling camp: “… this gathering of Canadian officers [have] come from every part of the Dominion and belong to every walk of life, united in the Mother Country and proclaiming the solidarity of the English peoples.”20 The fact that Vanier made no distinction between the ‘mother country’ and the ‘adopted mother country’ can be attributed to his dual identity as French Canadian and British (the Republic of Ireland had not yet been proclaimed). Of all the authors studied, he is the only one to refer to the imperial troops as his “brothers-in-arms.”21

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/ PA-002777

Major Georges Vanier, circa 1918.

In a diary entry on 2 September 1915, Vanier described a royal inspection as: “… a moving spectacle. The best day of my military life [translation].” He was not the only Van Doo to be impressed by a royal visit.22 However, even though a passive respect for British traditions may have helped the 22nd Battalion enter into the spirit of the CEF, the battalion did not practise those traditions actively. Although Thomas-Louis Tremblay had fought long and hard for the right to send his battalion to cover themselves with glory on the battlefield, he never competed for royal favour. He mentions that, on 14 August 1916, when the 24th and 25th Battalions were vying to obtain a visit from King George V, he “… made no overtures at all; it would have been pointless in any case [translation].”

The relationship between the British Army and the 22nd Battalion seemed to be less tight-knit than that between the English Canadians and the French Canadians. None of the authors studied (except Vanier, as cited earlier) relates such stories of cooperation between the British and the French Canadians. On the contrary, Tremblay reports friction. On 17 July 1916, he writes that at Dickebush, in Flanders, a group of British soldiers mocked some signallers from the 22nd Battalion, saying, “‘Look at the darn Colonials.’ Sgt Lavoie arrested the seven ‘blokes,’ to the section’s great amusement … That Lavoie is a good man and a real ‘Canayen’ [translation].” Similarly, Tremblay wrote in his diary entry for 2-16 January 1918 that a soldier “… punched and knocked down three English policemen in Bailleul because they were insulting the 22nd; he would die for his battalion [translation].” In Tremblay’s view, the honour of his battalion was more important than being polite to the imperialists.

Thus, despite Canadian propaganda efforts, the Van Doos had much stronger patriotic feeling for France than for Britain.

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/ PA-002764

Officers of the 22nd Battalion watering a horse, under the close supervision of a dog.

France

On 13 September 1915, Captain Francoeur wrote: “We are on our way to France, our hearts full of fighting spirit, with the firm resolve to conquer or die. Duty calls us, and we must obey … May God protect France [translation]!”

Francoeur’s brothers in arms wholeheartedly shared his euphoria. Vanier noted in his diary on 14 September 1915: “I am left with an indelible impression of the passage [from England to France]. In France at last … I could not have hoped for more [translation]!” According to his entry for the next day, that enthusiasm was widespread among the members of the 22nd Battalion: “The men … are very uncomfortable in a baggage car … with no seats or lights … they are not complaining; on the contrary, when we pulled out of the station at Le Havre they were singing the ‘Marseillaise’ and ‘O Canada’ [translation].”

But once they were deployed at the front in the French campaign, the Van Doos quickly realized that their idealism was unreciprocated. Many people who lived in the French countryside did not even know French Canadians existed. All of the authors studied mention this culture shock, but Vanier reflected upon it at greater length: “The people hardly understand how we happen to speak French and wear khaki. Very many of the French inhabitants were ignorant of our political existence as a race apart in Canada … We have opened their eyes and their hearts.”23 Francoeur presented himself as an ambassador for Canada, but Vanier positioned the 22nd Battalion as an ambassador of the French-Canadian ‘race.’

On 17 September at St-Omer, a French headquarters sent an interpreter to the 22nd Battalion. Obviously, the 22nd sent him back.24 Despite this misunderstanding, the personal diaries examined here do not show indifference on the part of the French toward their North American cousins, but rather a certain ignorance—which, however, did not extend to all of France. Tremblay, writing on 11 March 1916, reported: “We had a visit from a party of ten French officers. They were very interested in our men, who reminded them of their countrymen from Picardy and Normandy [translation].” In the end, the initial surprise turned to a more welcoming attitude, and the marraines—French women who wrote encouraging letters to the Van Doos and who might offer them hospitality during their leaves—made leaves in France more agreeable than those in London, which were constrained by the language barrier.25

In addition to their hospitality, the French impressed the diarists with their military bravery. Vanier wrote, “The French are splendid, their dash and determination are wonderful and I feel like saluting every man and woman I meet from the most gallant and boldest nation in the world … if we had more like them in Canada, we would be a noble, a better race.”26 On 5 December 1915, Tremblay told of a French officer coming to share information about French operations since the beginning of the war: “It made us realize the infinitesimal part we have played on this earth, and the greatness of Joffre and the French Army [translation].” Clearly, Vanier’s and Tremblay’s French-Canadian nationalism accepted the superiority of France and considered that country an example to follow. Indeed, Tremblay followed the example as an individual; he learned on 29 May 1917 that he would be awarded the Légion d’honneur: “That is the very decoration that means the most to me [translation].” As France’s highest honour, it was more important to him than the Victoria Cross, the highest military distinction in the British Army. Vanier’s admiration extended to the French peasant class: “The more I see of it … the more my admiration for the French nation and my faith in the triumph of Latin civilization grow [translation].”27 In his diary entry for 27 March 1918, he explains the reason for his admiration: “Being in contact with these poor people who are fleeing from barbarism … is inspiring; we consider it a great privilege to be able to contribute, even in the smallest measure, to the defeat and expulsion of the savages [translation].” Thus, the idealism about France that had existed before the war grew on the European front when Vanier came into contact with the people of that beloved nation.

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/ PA-000262

In the trenches. 22nd Infantry Battalion, July 1916.

The French Canadians’ patriotic feeling for France, their mother country, seemed to elicit a sense of duty. On 17 September 1915, Vanier wrote in his diary: “Never in my wildest flights of imagination could I have foretold that one day I would march through the country I love so much in order to fight in its defence.” He expressed similar sentiments in a letter to his mother dated 27 January 1916, in which he also referred to the war of 1870 to show that the destinies of France and the 22nd Battalion were interwoven. And that sense of duty was felt not only by officers. On 3 June 1917, Lapointe wrote an account of a mass celebrated at the church in Petit-Servins:

The emotion was palpable among the civilians who attended the military mass, when one of our guys started singing, in a warm and penetrating voice, the hymn “Dieu de clémence, ô Dieu vainqueur, sauvez, sauvez la France.” The battalion then took up the chorus, and, in the midst of the voices that rose powerfully to fill the nave, there was something that sounded like a sob. [translation]

Such devotion for a country other than one’s own had its effect on the people of France. When the Van Doos sang while passing through Bully-Grenay the night before an advance, the villagers came out to meet them, kissed them, and wished them “success against the dirty Boche.” In Captain Henri Chassé’s view: “It was a magnificent and charming spectacle to see old France applaud young France, ready to die for her [translation].”28 The French Canadians were receptive to the gratitude of a people for whom they said they were willing to sacrifice themselves. One can see how such a scene could spark the men’s fighting spirit. When it was announced that they were leaving for Flanders on 10 November 1917, Lapointe wrote: “The good news of our return to France was welcomed with immense joy.” Their patriotic feeling for France seemed to have a salutary effect on the morale of the troops.

The admiration, friendship, and sense of duty that the Van Doos developed for the people of France were a recurring theme in our authors’ writings for the duration of the war, and those feelings were not the result of a momentary burst of enthusiasm generated by the crossing to the mother country. Upon returning to Canada, Lapointe ended his diary with these words: “Despite the horrible nightmares that sometimes disturb my sleep, I can console myself with the thought that I have been useful to my country and have paid my debt of gratitude to old France [translation].”29

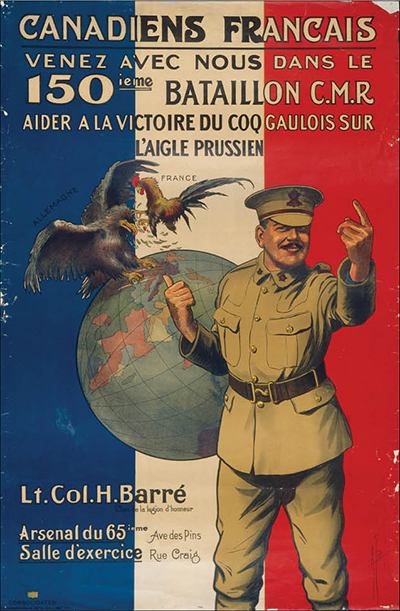

: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-28-789

Recruiting poster

French Canada

As mentioned earlier, although the Van Doos saw Canada as their native land, the French-Canadian nation was the one for which they were fighting. At the time of his departure from Amherst on 21 May 1915, Tremblay placed that idea in its historical context: “We can no longer see the beautiful land of Canada, and we are more determined than ever to prove that the French-Canadian blood flows just as purely and warmly in our veins as it did in those of our ancestors [translation].” Although Francoeur was occasionally an exception to the rule when he spoke of fighting for Canada, he expressed his patriotism toward French Canada more strongly: “If we soon have the opportunity to show all of our allies what a French-Canadian regiment can do in a bayonet charge, we are ready and we are only waiting for the order to advance. Then every country will know our worth [translation].”30 The 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion, by making the people it represented a part of its name, had given the Van Doos something meaningful for which to fight. Tremblay also wanted the members of the battalion to share his point of view:

I am confident that the French Canadians will defend all their trenches with fierce vigour and will hold on at any price, even the price of death. Let us not forget that we represent an entire race and that many things—the very honour of French Canada—depend upon the manner in which we conduct ourselves. Our ancestors bequeathed to us a brave and glorious past that we must respect and equal. Let us uphold our beautiful old traditions.31 [translation]

That was what Tremblay considered to be his mandate as commanding officer of the 22nd Battalion.32

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/ PA-002045

22nd Battalion resting in a shell hole on their way to the front line, September 1917.

And he felt that he had fulfilled that mandate with the victory at Courcelette. Before the battle, a war council had been held at the division headquarters. The lieutenant-colonel had had to argue for “… the honour of leading his battalion at Courcelette. He got his way [translation].”33 Just before launching the decisive attack, he rode along the trench on horseback and delivered this speech to his troops:

We are about to attack a village called Courcelette. We will take that village, and once we have taken it, we will hold it to the last man. This is our first big attack. It must succeed, for the honour of all the French Canadians whom we represent in France [translation].”34

The final moments before an attack were no time to give a political lecture; the only objective was to rouse the troops’ fighting spirit. Tremblay chose to speak of French-Canadian honour because he believed that the idea could galvanize his men, and that his pride in his ‘nationality’ would strike a chord with them. The 22nd Battalion was not obliged to lead the attack on Courcelette; the commanding officer fought for the opportunity because he believed that the benefits would outweigh the sacrifice of human lives.35

Although this French-Canadian patriotism involved a sense of duty and pride at participating in the major issues facing the Western world, Tremblay saw it as more than just a matter of personal satisfaction. Clearly, recognition was also important to him. That explains his indignation on 18 September in response to the lack of interest shown by his superior, the Commander of the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, Brigadier Archibald Cameron “Batty Mac” Macdonell, to the events at Courcelette, as well as his obvious appreciation of the generals’ compliments and the ovations from the other CEF troops. Tremblay wrote that he felt very ill less than 24 hours after being relieved at Courcelette—on 23 September, he was evacuated for treatment of his hemorrhoids, and he did not return to the front for five months. One wonders at the strength that enabled him to take part in the battle, which he led from in front rather than staying in the rear, away from the bullets. Tremblay and Vanier, who were both convalescing at the same time, were keen to read about the exploits of the 22nd Battalion in the French and British newspapers. Tremblay mentions the Times of London (21 and 25 September), the Manchester Guardian, the Mirror, the Standard and the Daily Mail, among others: “Their version of the attack is not quite accurate … The important thing is that the battalion is mentioned in the English newspapers as a unit that distinguished itself at the front [translation].”36

Courtesy of NCC, Governor General of Canada, portrait of Georges P. Vanier by Charles Fraser Comfort, 1967

The Right Honourable Georges Philias Vanier became Governor General of Canada at the end of a distinguished career as a soldier and diplomat.

From then on, the battalion’s pride crystallized around the Battle of Courcelette, which became the model to be emulated. When he returned from sick leave on 14 February 1917, Tremblay reaffirmed his mandate: “As I retake command of my battalion, I am full of confidence in the future, realizing … more than ever my weighty responsibilities, determined to ensure that the glory of Courcelette did not fade [translation].” (Coincidentally, the complete motto of the Royal 22e Régiment today is “Je me souviens du passé, j’ai confiance en le futur.” [I remember the past; I have confidence in the future.”]) On 14 August 1917, Lapointe reported a speech Tremblay delivered before the Battle of Hill 70, and added his own comment that shows the influence the commanding officer had on the morale of his troops:

“Tomorrow, you will fight as you fought at Courcelette and at Vimy, and back home our people will be proud of you.” Our commanding officer is not very eloquent, but all the soldiers of the 22nd know his legendary bravery, and every word he speaks has great significance for us [translation].37

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/ PA-004284

Brigadier-General Thomas-Louis Tremblay, later in the war.

In the same vein, after his return from sick leave, Tremblay began to speak of the “old originals,” the veterans of Courcelette, whom he used as an example for the new recruits. During his absence, under the acting command of Major Arthur Edouard Dubuc, discipline had slackened, particularly after the arrival of 220 new officers and men in September 1916, and 380 in October 1916 to replace those lost at Courcelette and in the Regina Trench. The reinforcements arrived so quickly that there had not been time to instil in them the esprit de corps of the “old originals,” a spirit that had been cultivated since the beginning of training back in Saint-Jean a year earlier. As renowned Canadian historian Desmond Morton has noted, seven Canadian soldiers executed by firing squad during the First World War were French-Canadian, and five belonged to the 22nd Battalion—an over-representation. Jean-Pierre Gagnon points out that all of the executions were carried out on the recommendation of a single commanding officer: Thomas-Louis Tremblay. To restore the discipline that had been eroded during his five months of convalescence, and to preserve the hard-earned reputation paid for by the blood of the men who had died in combat, Tremblay took the drastic step of executing deserters and criminals.38 It is important to realize that the consequences of a defeat for the 22nd Battalion on the European front would have been very serious, given the experimental nature of the first Francophone battalion. Perhaps there would not be as many French-Canadian units, and bilingualism would not be so widespread in the Canadian Forces today if the 22nd Battalion had brought shame to the French-Canadian nation. In any case, the executions and his insistence upon leading his battalion to the front39 demonstrate that Tremblay’s nationalism went beyond mere thought and speech: he followed through—sometimes radically—with decisions and concrete actions.

In 1917, the Van Doos’ nationalism was expressed primarily in reaction to the news from home of French-Canadian protests against conscription, which culminated in riots in Quebec City in 1918. Clearly, the soldiers of the 22nd were not ignorant of the Canadian political situation. On 7 February 1917, Lapointe wrote: “I know people back in Canada … who will spit with contempt when they think of us, and will repeat … that we have no reason to risk our lives for France and England. However, if those countries had been left to fend for themselves, what would have happened?” Without claiming that the 22nd Battalion had come to save France and Britain by itself, Lapointe was aware that its presence compensated for the indifference of Francophone Quebeckers back home to the situation in Europe. On 27 November 1917, Tremblay related his hostile altercation with Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, over disgraceful articles about the 22nd Battalion that had appeared in the British newspapers. The rest of the entry in his war diary countered Beaverbrook’s criticism, praised the 22nd Battalion, and admitted that English Canada would like more French Canadians to enlist. But, above all, it asserted that “… right now, the 22nd is saving Quebec’s reputation.” Tremblay’s traditional mandate had expanded: now, in addition to representing the French-Canadian nation, the 22nd Battalion would have to compensate for Quebec’s feeble contribution to the Allied war effort. On 5 August 1918, as was his habit, Tremblay protested to his general concerning the fact that the 22nd was to be relegated to a secondary role during an attack at Amiens. He ended by admitting: “Perhaps the practical situation at home is the cause of my disappointment [translation]!” Four months earlier, during an anti-conscription riot on 1 April, four Quebec civilians had been killed by troops from Ontario.

CWM 19710261-0056 by Alfred Bastien, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum

‘Over the Top,’ the 22nd Canadian Infantry Battalion at Neuville-Vitasse on the heavily-fortified Drocourt-Quéant Line, August 1918.

Conclusion

The presence of the Van Doos on the Western Front ultimately shattered Quebec’s isolation from and indifference to major international issues. From the time they landed in France, the French Canadians were not fighting for the survival of their people, but were attempting to achieve glory by contributing to the Allied war effort. Tremblay, Vanier, Lapointe, Francoeur, and some of their brothers-in-arms openly affirmed their patriotism and their national allegiances. This study has documented a break with French Canada’s “nationalism of resistance”—which was expressed primarily through anti-conscription sentiment—and a shift to “participatory nationalism,” as revealed in the war diaries [and letters-Ed.] of members of the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion. In the midst of the turmoil caused by the exaggerated and sometimes imperialistic nationalisms that were among the causes of the Great War, this “participatory nationalism,” which recognized the superiority of France, was distinguished by the fact that it aspired to fulfilment and recognition, rather than dominance.

Canada. Department of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/ PA-003778

The 22nd Canadian Infantry Battalion crossing the Rhine River at Bonn, December 1918.

NOTES

-

At least, that was the vision of his commanding officer, Thomas-Louis Tremblay, as expressed in a speech to his troops just before the Battle of Courcelette. Thomas-Louis Tremblay and Marcelle Cinq-Mars, (eds.), Journal de guerre (1915–1918) [War diary, 1915–1918] (Quebec City: Athéna Éditions (Collection Histoire militaire) and Royal 22e Régiment Museum, 2006), 15 September 1916 entry.

-

The term ‘nationalism’ is used in this article to refer to the sense of honour and duty toward French Canada. Thinkers who promoted the idea of a French-Canadian nation (i.e., Abbé Lionel Groulx) were not prominent in the public sphere at the time. Authors of the time, and more specifically, the authors of the war diaries and letters examined here, expressed nationalism more in terms of pride and patriotism.

-

Joseph Chaballe, Histoire du 22e bataillon canadien-français, Tome I : 1914–1919 [History of the 22nd French Canadian Battalion, Volume I: 1914–1919] (Montreal: Éditions Chanteclerc, 1952), p. 42.

-

Account preserved in Les archives audio de la Première Guerre mondiale [First World War Audio Archive]: Georges Francoeur, at <http://www.veterans.gc.ca>, accessed 11 August 2011.

-

Tremblay, 20 May 1915: “Our men and our officers freely admit that our stay in Amherst was more pleasant than our stay in the province of Quebec [translation].”

-

Claudius Corneloup, “L’Épopée du vingt-deuxième” [The epic of the 22nd],” La Presse (Montreal), 1919, p. 17.

-

A/R22eR, FPA69, Georges-Ulric Francoeur, Journal de guerre, 1915–1916 [War diary, 1915–1916], 4 October 1915.

-

After Courcelette, Corneloup (p. 61) wrote, “Quietly but genuinely moved, the men of the 22nd and the 25th, the first French and the second English, no longer wanted to be separated [translation].”

-

On 21 August, Tremblay wrote, “I gave instructions accordingly. The result was quite amusing. A soldier who did not swear told his little story in about three minutes; the one who swore a blue streak took about six minutes. Some ‘Six-Bits’ [nickname of the 75th] are splitting their sides tonight [translation].”

-

In particular, see the entry for 14 May 1916 on the laxity of the 20th Battalion concerning the repair of a parapet, or the entry of 6 June 1916 on the carelessness of the 12th York Battalion of Infantry concerning reconnaissance missions.

-

However, it is worth mentioning two exceptions to this trend. Both are from Francoeur’s diary. On 5 October 1915, he wrote that the Boche “… would have their hands full if we are ever ordered to advance; they will find out what young Canadians can do [translation].” On 24 October, during a mass at the church in Locre, Captain Doyon, the battalion chaplain and member of a church that was anxious to preserve the established political order, explained to the troops, “… if we must die, let our death serve the Homeland [translation].”

-

Georges Francoeur, Journal de guerre, 31 December 1915. This opinion was echoed elsewhere—for example, in Francoeur, Journal de guerre, 26 December 1915 and 17 January 1916; and Georges Vanier, letter to his mother, 23 May 1915.

-

Quoted in Francoeur, Journal de guerre, date unknown, 1916. Given the prevalence of trench foot, one can understand why the fantasy of the comforts of home was expressed in a song celebrating dry socks.

-

A.J. Lapointe, Souvenirs d’un soldat du Québec: 22ème Bataillon, 1917–18 [Memories of a Quebec soldier: 22nd Battalion, 1917–18](4th edition) (Drummondville, QC: Les Éditions du Castor, 1944), 6 February 1919.

-

Corneloup, p. 65: “His character, his sentiment, his race, his very religion barred him from entry; and even if he dared to try his luck, the French Canadian would be met with shrugs and pity [translation]!”

-

Ibid.., p. 33: “Belonging to another race … this battalion … seemed lost in the midst of this formidable army raised by England … no battalion … was more watched or more criticized [translation].”

-

On 27 October, concerning the visit of King George V, King Albert of Belgium, Maréchal Ferdinand Foch and General Joseph Joffre, Francoeur wrote: “We were so surprised to see them and we were so busy watching them pass by that I wonder whether we presented arms. I don’t think so [translation].”

-

Robert Speaight, Georges P. Vanier : Soldat, diplomate, gouverneur general [Georges P. Vanier: Soldier, diplomate, governor general](Montreal: Éditions Fides, 1972), p. 40.

-

Tremblay maintained this opinion despite his amazement when he (a single man) discovered that his marraine, of whom he had had such high expectations, was a fat old lady! For more on French hospitality, see Vanier, letter to his mother, 14 September 1915; and Vanier, Journal de guerre, 15 September 1915 and 17 November 1915. For another mention of French ignorance, this time not in the countryside, but in Paris, see Francoeur, Journal de guerre, 14 March 1916.

-

Georges Vanier, letter to his mother, 30 September 1915. See also his diary entry for 16 September 1915.

-

Lapointe,14 August 1917; Henri Chassé, quoted in Speaight, p. 66.

-

Georges-Ulric Francoeur, Journal de guerre, 20 December 1915.

-

At the time of his appointment on 26 February 1916, he reiterated this mandate: “I am perhaps the youngest Bn commanding officer at the front. My battalion represents an entire race; it is a heavy responsibility. Nonetheless, I have confidence in myself and I feel that my men respect me. My acts will be guided by our inspiring motto, ‘Je me souviens’ [translation].”

-

On 18 September, Tremblay wrote, “Unfortunately, the proportion of men killed is large, perhaps 40%. We have paid dearly for our success; our consolation is that those sacrifices were not made in vain, that one day our nationality will benefit from them [translation].”

-

Tremblay, Journal de guerre, 27 September 1916. See also Vanier, Journal de guerre, 21 September 1916; letter to his mother, same day; and letter to his mother, 24 September 1916.

-

The diary of the 22nd Battalion continues the account of Tremblay’s speech: “Tonight the eyes of French-Canada are turned towards us, and I expect every man to do his duty, and more than his duty, that the hopes of those who have put their trust in us may not be disappointed.” Appendix M to August War Diary, p. X, August 1917.

-

Desmond Morton, The Supreme Penalty: Canadian Deaths by Firing Squad in the First World War, quoted in Jean-Pierre Gagnon, Le 22e bataillon (canadien-français) 1914–1919 [The 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion, 1914–1919] (Quebec City: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1986), p. 279. Gagnon discusses the issue on pages 279–308.

-

In addition to Courcelette, Tremblay pushed to be allowed to lead his battalion at the front of the attack on Vimy Ridge, but the brigadier-general wanted to give other battalions a chance to distinguish themselves as the 22nd had at Courcelette (see Journal de guerre, 27 March 1917). On 1 July 1917, Tremblay writes that despite his promotion to brigadier-general, he continued to exercise his influence in the effort to have “his” battalion lead a mission at Lens.