Military History

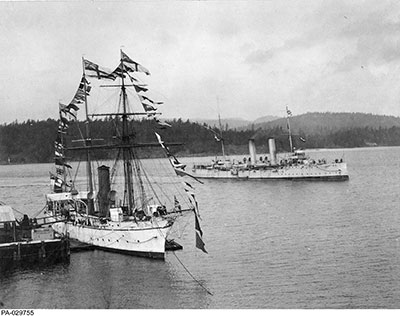

Library and Archives Canada PA-029755

HMCS Shearwater and HMCS Rainbow in 1910.

The Naval Service of Canada and Ocean Science

by Mark Tunnicliffe

Commander (ret’d) Mark Tunnicliffe is currently a Defence Scientist with Defence Research and Development Canada at National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

The Canadian Navy was born joint. Not ‘joint’ in the sense of some affiliation with the army or the air force (which, of course, did not exist at the time), but integrated with the other marine arms of the Government of Canada with which it had a common professional background and national objective – namely, security in the Canadian maritime environment and national sovereignty. The authority for the institution of a Canadian navy was The Naval Service Act, which was assented to on 4 May 1910. That Act established the Department of the Naval Service, which was initially presided over by the Minister of Marine and Fisheries, who retained sole authority and responsibility for its management and operation. In addition to the combat capability traditionally associated with navies, Section Two of the Act declared that: “[The Canadian] ‘naval Service` includes, besides His Majesty’s service in respect of all naval affairs of which by this Act the Minister is given control and management, and also the Fisheries Protection Service, Hydrographic Survey, tidal observations on the coasts of Canada, and wireless telegraph service.”1

The Department, therefore, was initially organized into the five branches specified by the Act: Naval, Fisheries Protection, Tidal and Current Survey, Hydrographic Survey, and Wireless Telegraph.2 Thus comprised, the Department actually commanded a fairly sizable number of ships in addition to the two naval vessels which initially equipped the Naval Branch. Its Fisheries Protection Branch, whose assets had been transferred from the Department of Marine and Fisheries, had antecedents which extended back to the Provincial Marine services in existence well before Confederation, and it was already operating as a quasi-military organization. In 1910, it brought a fleet of eight fisheries cruisers (under the command of Rear Admiral Charles Kingsmill) into the Department of the Naval Service, including the armed CGS Canada, and the “first modern warship to be built in Canada,” CGS Vigilant.3

Library and Archives Canada Acc. No. 1937-179-1

Admiral Sir Charles E. Kingsmill.

The Hydrographic Service, under the direction of the first Canadian Chief Hydrographer, William Stewart, also brought a small fleet of vessels to the Department – some chartered, some borrowed from other departments. Some, however, like CGS Lillooet – “… the first officially designated and constructed vessel in the hydrographic fleet,”4 - were modern purpose-built vessels owned by the Department. Finally, the Tidal and Current Survey Branch conducted operations from the old steamer CGS Gulnare, using her to communicate with its 11 permanent tidal stations. Consequently, when the Department of the Naval Service of Canada was born, it was already provided with a relatively comprehensive fleet of little ships even before the arrival of its first two military units, HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow, some five and six months later respectively.5

The composition of a navy which included a fleet of survey ships was not unusual, and for an institution whose purpose was to provide a “… security for such as pass on the seas upon their lawful occasions,”6 it was particularly appropriate for a nation such as Canada, where uncharted waters and unmapped currents were generally more hazardous to shipping than acts of an enemy. In Great Britain, hydrographic survey was (and remains) a function of the Royal Navy (RN), and, to this day, the RN’s fisheries protection squadron remains its oldest front line unit. It is therefore not surprising that the newborn Naval Service of Canada would copy the structure of its parent. Since these non-military branches of the Service were already well established Canadian institutions in May 1910, their activities tended to attract much of the attention of the Department of the Naval Service in its formative years. The early history of the Naval Service of Canada therefore was dominated by programs of exploration, survey, and research – programs that continued throughout the First World War. Canada’s new navy was very much a technical and scientific organisation, which played a significant role in mapping and surveying the maritime environment of a still-young nation.

DND SU2007-0281-05a

HMCS Niobe at Daybreak, by Peter Rindlisbacher.

Research, Survey, and Exploration under the Department of the Naval Service

The challenge to Canada’s maritime sovereignty in its early years stemmed, not so much from direct foreign intervention, but rather in defining and charting its boundaries (particularly in the Arctic), and in demonstrating competence in executing domestic authority and responsibility for safe navigation and commerce in its internal waterways and adjacent seas. Consequently, the activities of the Naval Service of Canada in its early years with respect to pursuing this mandate were marked by considerable interest from Parliament and the public. This interest was often expressed in the provision of additional generally ‘state-of-the-art’ ships and equipment, that is, with the exception of the Naval Branch, which, as has been well documented elsewhere, was almost immediately left to languish.

Survey and Exploration

The Royal Navy’s hydrographic service had initially looked after much of Canada’s maritime survey requirements, albeit subsidized by the Dominion government. However, the demands of inshore navigation on the Great Lakes (facilitated by the development of steamships), and stimulated both by U.S. surveys in their portion of the Lakes and by the traffic occasioned by increased immigration, prompted the Dominion government in 1883 to obtain the services of Staff Commander Boulton from the RN to commence a survey of the waters of Georgian Bay.7 With this initiative, a national hydrographic survey capability was born, managed within the Department of Marine and Fisheries. Other similar work was also being undertaken by hydrographic units established by the Department of Public Works and by the Department of Railways and Canals, as part of its development operations. In 1904, however, all these operations were consolidated in the Canadian Hydrographic Survey, then being directed by Boulton’s former assistant, William Stewart. It was a timely consolidation, because in that same year, the RN, as part of its consolidation of the British fleet to home waters, withdrew its hydrographic support to the ‘colonies.’ It did so with the ‘parting shot’ that the current coastal surveys and charts for colonial waters were now quite inadequate for modern inshore navigation. The new hydrographic service would have its work cut out for it.

By the time the Canadian Hydrographic Survey was transferred to the navy in 1910, it was executing seven survey programs. In addition to the work on the Great Lakes, the requirements for the east and west coasts, inland waters and Hudson Bay were also being addressed. It was the latter survey program that got the Naval Service of Canada almost immediately involved in Arctic exploration. Britain, which had conducted much (but not all) of the initial exploration of the high Arctic, had transferred its claims to sovereignty in the area to Canada in 1880, but the young Dominion had done little to assert these inherited rights. Indeed, much of the exploration of the north-west Arctic to this point had been conducted by Norwegians, notably Roald Amundsen and Otto Sverdrup. Fortunately, Norway did not press any claims to the area, based upon their exploration, and, in 1903, the Canadian Government purchased Sverdrup’s charts in an attempt to assert Dominion sovereignty over the entire Arctic Archipelago.

Hudson Bay

Sovereignty was not the only issue driving northern maritime development. With increased immigration to the west and concomitant commercial traffic to the new settlements established there, developers were looking for shorter rail routes to handle the expanding western grain trade. One option that appeared attractive was a rail route to Hudson’s Bay – if the issues of ice and inadequate hydrographic and tidal surveys in that area could be solved. Initial investigations into these challenges had been taken in the 1880s by the Department of Marine and Fisheries on three expeditions intended to investigate the impact of ice upon the navigation season. While voyages of exploration and sovereignty claim were continued by the Department of Marine and Fisheries after the inauguration of the Naval Service, meeting the demands for safe navigation in Hudson’s Bay now fell under the new department’s mandate. Shipping required not only accurate charts and surveys of the approaches to potential railheads, but also a thorough understanding of local tidal and current conditions. Additionally, navigation in the high arctic created a wrinkle for ships piloted solely with the aid of magnetic compasses: the need to cope with the rapid changes of magnetic declination in the region.

Consequently, the Department of the Naval Service dispatched Commander Miles of the Hydrographic Survey with the experienced Newfoundland ice pilot, S.W. Bartlett, to conduct a preliminary investigation of Hudson’s Bay. Their objective was to determine the impact of ice upon the navigation season, and, in particular, to make a determination between Churchill and Port Nelson as the optimal port terminus for the proposed western railhead. Using the ice-breaking steamer Stanley loaned from the Department of Marine and Fisheries to act as a mother ship for a small schooner and survey boats, Miles conducted an initial survey during the summer of 1910. The results were sufficiently encouraging that the Department of the Naval Service sent the team back again the following year, this time with the support of the icebreaker Minto and two survey schooners, Chrissie Thomey and Burleigh, which were purchased for the purpose. The team deployed three parties that conducted detailed surveys of Port Nelson and Churchill and surveyed the magnetic declination changes in Hudson Bay. This work continued for the next two years, and this effort was augmented in 1913 by an additional asset.

Library and Archives Canada PA-045204

Hydrographic Survey Schooner (HSS) Chrissie C. Thorney on the Nelson River, Manitoba, circa 1910.

That asset was the steamer CGS Acadia, built at Newcastle-on-Tyne, Great Britain, to Canadian specifications, and it had arrived in Halifax in July of that year. Commanded by Captain F. Anderson of the Hydrographic Branch, she was quickly put to work, and by the middle of August, she was anchored off Port Nelson in Hudson Bay. This 12 knot, 1700 tonne ship was purpose-built for the task, and was specially strengthened for navigation in ice, “… proving to be a first-class sea boat [that] gave a very good account of herself in any ice encountered.”8 Her special construction was soon put to the test by heavy weather that autumn, and it was not long before she became involved in the rescue of 28 seamen from the steamer Allete,an event eagerly tracked by the Canadian public, that was fed daily details of the event via the ship’s wireless - the first electronic equipment to be fitted in any Canadian survey vessel.

By the beginning of the First World War, the Hydrographic Branch had effectively assumed responsibility for survey work in Canadian waters from the Royal Navy (RN), and was conducting a vigorous program of work with a ‘cutting edge’ fleet of vessels – many of them quite new. CGS Lillooet, supplemented by the new schooner Naden, was charting the British Columbia coastline; CGS Bayfield and La Canadienne the Great Lakes; CGS Cartier, the Lower St. Lawrence River; and CGS Acadia, the Atlantic Ocean and Hudson Bay. Unfortunately, the Chrissie Thomey had, by 1913, become a permanent fixture of the Hudson Bay shoreline. Being too badly damaged by the ice, she was beached and converted into a shore-bound base ship.

Library and Archives Canada PA-048309

CGS Cartier and SS Sable Island resting anchor in Harrington Harbour, Quebec, probably during the inter-war years.

The Canadian Arctic Expedition: 1913 – 1916

By the turn of the century, stimulated to some extent by American enquiries into the sovereignty of parts of the Arctic Archipelago, the Dominion began extending its interest in Canada’s maritime frontier to the north as well. This concern was the impetus for the legendary expeditions by Captain J. E. Bernier in his wooden ship CGS Arctic under the sponsorship of the Department of Marine and Fisheries. Conducted from 1904 and into the 1920s, with the primary objective of formally cementing Canada’s claims of sovereignty in the eastern high arctic, these expeditions were crowned by Bernier’s claim, made on Dominion Day 1909, of the entire Arctic Archipelago for Canada, which he commemorated with a tablet placed on Melville Island. Unfortunately, this was about as far west as he was able to force his little ship.

Since, as noted earlier, exploration of much of the north-western portion of that archipelago had been accomplished by the Norwegians, Canada’s claim to that area was potentially open to question. Consequently, when, in 1913, the Canadian explorer and ethnologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson proposed to the Canadian Government that he lead an expedition to explore the western high arctic, the government enthusiastically responded with support and funds. While a number of departments backed the mission, the Department of the Naval Service was selected to lead it, and the Department placed Stefansson in charge.

The object of the expedition, which was divided into northern and southern components, was to determine if a new continent existed north of Alaska, and to conduct scientific observations on wildlife and current drift. The Department purchased the 247 tonne auxiliary brigantine Karluk, which Stefansson had previously obtained for $10,000, assigning the veteran Captain R.A. Bartlett to command her.9 Two smaller vessels, Mary Sachs and Alaska, were also obtained to support the southern portion of the expedition in its exploration of the western arctic mainland. Unfortunately, Karluk, a former US fishing supply ship, although reinforced for operation in the ice periphery, was poorly suited to the task of deep penetration into arctic ice. Indeed, her 150 horsepower “coffee pot of an engine” was, in the opinion of her engineer, quite inadequate for ice navigation.10

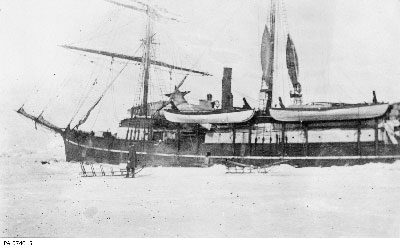

G.H. Wilkins/Library and Archives Canada PA-074045

HMCS Karluk drifting, October 1913.

Consequently, it was not long after she set sail from Nome, Alaska in July 1913 that Karluk became stuck in the ice and while Stefansson and some members of the northern party were off the ship on an extended hunting trip, Karluk, with the remaining members of the crew, was carried off westward. Finding her gone, Stefansson`s group was forced to hike back to Cape Smythe, near Barrow. By January 1914, Karluk had drifted far westward into the East Siberian Sea. By the 10th of January, she was so badly holed that Captain Bartlett had the men evacuated with supplies onto a camp on the drifting ice. In the best traditions of the new Service, Bartlett stayed with his charge, but the ship proved to be irreparable. The next day, to the tune of Chopin`s funeral march playing on Bartlett`s wind-up phonograph, and, ``… with the blue ensign at the main topmast head, the Karluk disappeared, going down in 38 fathoms of water ... 60 miles North by East of Herald Island.”11 Four of the party attempted to make Alaska on foot but were never seen again. When it was decided to attempt to trek to Wrangel Island, 60 miles to the south, an advance party of another four individuals set out to lead the way, but they also got lost, and were eventually found dead on Heard Island many years later. The remainder, led by Captain Bartlett, did reach Wrangel Island and set up camp there. At this point, Bartlett, with an Inuk companion, completed the remaining 110-mile trip over the ice to Siberia, and from there, shipped back to Alaska from whence a rescue expedition was mounted. Eventually, the stranded party was rescued in September 1914 by a trading ship and a US Coast Guard cutter.12

G.H. Wilkins/Library and Archives Canada PA-074048

Pilot house aboard the HMCS Karluk, August 1913.

This setback was not fatal to the expedition, however, and Stefansson, who had returned over ice to Alaska, purchased another ship, North Star, and continued his exploration. Over the next two years, it would take him north along the coast of Banks Island and still further north to Prince Patrick Island, where he discovered a cairn left by the McClintock expedition of 1853. Yet, even further north, he discovered a new coastline, the southern shore of the Queen Elizabeth Islands, which had not been previously charted. His travels, which involved buying several more small vessels for support, were largely undertaken by sled over land and ice, and were generally supplied by living off the land. While he was no doubt a very controversial character, Stefansson was a hardy and competent explorer and, aside from an engineer in one his schooners who had suffered a heart attack, no more members of the expedition were lost. He remained in the Arctic until 1918, discovering a number of new islands in the western Arctic and demonstrating that it was quite feasible for non-native people to survive there indefinitely if they adopted the Inuit lifestyle. His degree of competence, or perhaps nonchalance, is no doubt illustrated by the quote often ascribed to him: “Adventure is a sign of incompetence.”

The southern division of the expedition, led by Doctor R. Anderson and supported by the schooners Alaska and Mary Sachs, pursued a variety of other objectives over the same three-year period. These included a survey of the western mainland coast, and the southern portion of some of the islands of the western archipelago, geological investigations (primarily prospecting for copper ore), Inuit ethnology and language, arctic zoology and botany, tidal measurements, magnetic survey, and meteorological observations. The division’s activities concluded in August 1916 with such an extensive collection of specimens and samples that it had to be distributed internationally for analysis.

Despite its less-than-promising beginning, the Canadian Arctic expedition of 1913 – 1916 achieved all the objectives assigned to it, and, in so doing, it reinforced Canadian claims of sovereignty in the western arctic. In particular, the efforts of Captain `Bob` Bartlett to rescue his crew established a standard of endurance, leadership, competence, and courage that captured the attention of Parliament and the Canadian public.13 Scientific investigation under these circumstances could indeed demand of Canadians much the same qualities of character, endurance, and courage that the Canadian Corps was now drawing upon at the Western Front.

The Canadian Fisheries Expedition 1914 – 1915

The Department took rather less notice of another initiative in ocean research it sponsored during the same time frame, but one which ultimately would have a more direct benefit to the operations of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) in the next war. The science of biological oceanography and its practical value to the fisheries had been established in Europe by the expeditions of Doctor Johan Hjort, Director of Fisheries for Norway, and Sir John Murray of Great Britain. One of their investigations, conducted in the Norwegian fisheries research vessel Michael Sars, took them off the coast of Newfoundland in 1910, where nominal similarities in the ocean conditions to those in Norwegian waters were noted. Since the Norwegians had successfully exploited information on ocean characteristics to develop new fisheries, the president of the Biological Board of Canada persuaded Doctor Hjort to conduct a similar investigation off the east coast of Canada to determine if similar benefits to the Canadian fisheries could be identified. As the Board lacked the resources to support the work itself, it enlisted the support of the Deputy Minister for the Department of the Naval Service to underwrite it. The intent was to make physical, chemical, hydrographical, and biological surveys of the Atlantic coastal and Gulf of St Lawrence waters to determine the optimal conditions for further development of the Canadian fisheries. The Deputy Minister of the period, George Desbarats, agreed, and the Department of the Naval Service underwrote the costs.

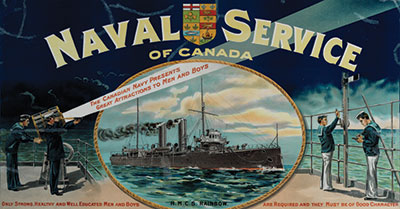

Canadian War Museum 19940001-980

Recruiting (Navy) poster, circa 1910.

Following some preliminary work in 1914, Hjort determined that there were a number of commercially viable herring populations which might be differentiated as a result of the impact of the ocean environment on their breeding cycles. Consequently, he proposed a program of biological and oceanographic observations, focussed upon the Gulf of St Lawrence and the waters off the Scotian Shelf. Two cruises in each location were planned – one in the spring of 1915 during spawning season, and the second in late-summer to note the migration of the resulting herring young. The Atlantic cruises were conducted by the Naval Service’s hydrographic ship CGS Acadia, while the Gulf investigations were conducted from the Marine and Fisheries vessel Princess. Neither vessel was particularly well-equipped for this type of work, so Hjort had to bring with him some basic instrumentation from Norway, including Nansen bottles (for collecting sea water samples) and reversing thermometers. These were lowered to selected depths on 4mm wire operated from hand winches equipped with a meter wheel for noting the package depth. Biological samples were collected using a variety of plankton nets developed for the purpose by the Norwegians. These were some of the first relatively-extensive physical oceanographic measurements of Canadian coastal waters to be collected and subsequently analysed.

The work was evidently not particularly popular with the navy. The Department of the Naval Service noted the deployment of Acadia in May, and again in August 1915, rather briefly in its annual report14 - with the effort seemingly viewed as somewhat of an interruption of the ‘real’ hydrographic survey work that Acadia was normally tasked to pursue. The final report of the expedition,15 which was eventually produced under the imprimatur of the Department of the Naval Service of Canada in 1919, comprised six papers on biological oceanography, and two on the physical oceanography of the area. The report proved to be the foundational work for the science of oceanography in Canada, and the portion on physical oceanography was characterised as “… the treatise on hydrodynamics, which occupied a prominent part of the report, has for 50 years continued to be valued as a text. Further, the methods of investigation introduced into Canadian oceanography were to be adopted by Canadians in the years that followed.”16 However, the Department itself did not appear to be particularly impressed, as distribution of this foundational document was apparently fairly limited.17 Nevertheless, the RCN would find itself rather more interested in the subject of the thermal structure of Canadian coastal waters some 30 years later.

Conclusion

With the National Defence Act of 1922, the Department of the Naval Service ceased to exist, along with the RCN`s direct association with its other marine branches, The Hydrographic, Tidal, Fisheries Protection, and Wireless Branches were transferred back to the Department of Marine and Fisheries, while the Naval Branch joined the new Department of National Defence. With the nation thoroughly tired of war, the Navy now entered a period of severe retrenchment and budget cuts, with no mandate or interest in research and survey work.

That work continued, however, with the Department of Marine and Fisheries picking up the development of the nascent science of oceanography in Canada, driven, as it had been before, by the demands of the resource industries – primarily the fisheries. A physicist (and reserve army officer) H.B. Hachey, operating out of the Marine Biological Station at St. Andrews in New Brunswick, continued the investigations into the physical oceanography of Canada’s east coast that had been initiated by the earlier Fisheries Expedition. Extensive measurements were made of currents and sea temperatures in the Strait of Belle Isle, Cabot Strait, and the coastal waters of Newfoundland as part of a 1923 international survey conducted under the auspices of the North American Council on Fisheries Investigations. Additional work was conducted in the 1920s and 1930s in the Bay of Fundy area to determine the possible impact upon the fisheries of tidal power station development, again under bi-national sponsorship. Furthermore, a series of fisheries research expeditions were mounted to Hudson Bay between 1929 and 1931.

On the west coast, studies were conducted by biologists to examine the impact of the Fraser River discharge into the Strait of Georgia on marine fauna distribution and the influence of seasonal variation in water characteristics on fish populations. The physical and chemical aspects of this work were pursued by John. P. Tully, a chemist, at the biological station at Nanaimo, British Columbia, in 1931. Tully instigated a number of projects, including the first survey of the offshore oceanography of the waters around Vancouver Island with the aid of the RCN’s old battle class trawler, HMCS Armentières, from 1935 to 1938.

Library and Archives Canada PA-115560

HMCS Armentieres off Esquimalt, British Columbia, 9 December 1940.

While the involvement of the RCN in ocean science during the inter-war years was relatively small, the relationships established with marine scientists would be important to its technical development late in the Second World War, and also during the immediate post-war years. As explored elsewhere,18 the capabilities and infrastructure developed on both coasts by Hachey and Tully, and the data bases collected and established on the physical oceanography of the Canadian coastal waters, inaugurated by the Fisheries Expedition, and expanded upon by these individuals, would be key to understanding the performance and limitations of ASDIC (sonar) during the Second World War.

The exploration and survey work sponsored by the Naval Service of Canada under the auspices of its Hydrographic Branch played a significant role in exploring the boundaries of a rapidly expanding nation, and in establishing and demonstrating sovereignty over its high arctic frontier. Not surprisingly, there is little discussion of the activities of the Naval Branch in the unclassified annual reports of the Naval Service to Parliament during the war – the details were classified. Consequently, these reports focussed upon the activities of the Hydrographic Branch, and particularly, upon the dramatic exploits of Stefannsson’s Arctic expedition which excited the imagination of the Canadian public. For the Naval Service of Canada, the First World War was very much a ‘home game.’

Today, the navies of many nations retain responsibilities for maritime survey and hydrographic work similar to those responsibilities initially assigned to the Naval Service of Canada in 1910. In Canada, it has proven more useful to split the maritime sovereignty functions of defence and survey/exploration between DND and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). Collaboration between these departments (or their predecessors) has waxed and waned with the nature and intensity of the challenges facing the nation. Today, with increasing international and national interest in the Arctic, the navy, and Canada’s science-based institutions, are being increasingly called upon to support the nation’s interests and sovereignty claims to the region. Not surprisingly, therefore, cooperation between the two, and consequently, the role of DND in supporting arctic marine science and hydrography is increasing.

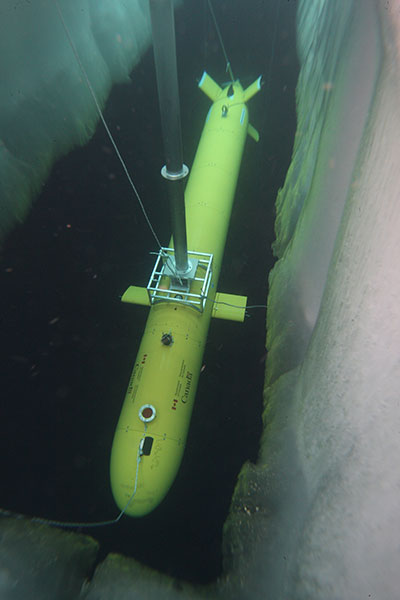

Photo by Gina Millar, ISE Control Systems Engineer, ISE Ltd.

NRCAN Arctic Explorer Yamoria over the ice.

Photo (ati unclos 2010_0394s) courtesy of James Ferguson, ISE Ltd.

Another view of Yamoria in suspension during Project Cornerstone.

This has been illustrated recently in the support provided by DND’s research arm, Defence R&D Canada (DRDC) to the combined National Resources Canada (NRCan,), DFO, DRDC project that used autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to conduct under ice surveys of the ocean floor north of Borden Island in Canada’s western arctic. In two surveys conducted in 2010 and 2011 respectively, Project Cornerstone19 used two Explorer AUVs that travelled over 1000 kilometres under the ice while conducting surveys of Canada’s extended arctic continental shelf in support of Canada’s claims for extended arctic sovereignty under the terms of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Surveying Canada’s maritime boundaries is still a work in progress and it probably will be for a long time to come. The conduct of marine science and survey in waters we claim our own is very much a statement of national sovereignty. Consequently, the interest of DND and the RCN in ocean science will also continue in both a lead and supporting role – just as it did when the navy was created 100 years ago.

Photo (OTT_10_6247) courtesy of James Ferguson, ISE Ltd.

Yamoria’s happy crew at project completion.

NOTES

- Text of the Naval Service Act as Passed in 1910, 9-10 Edw VII, c. 43 as reprinted in App V to G.N.Tucker, The Naval Service of Canada, Its official history, Volume 1: Origins and Early Years, (Ottawa, King`s Printer, 1952), pp. 377 – 385.

-

As reported in the introduction to Report of the Department of the Naval Service for the Fiscal Year ended March 31 1911 – Sessional Paper No 38, (Ottawa, King’s Printer, 1911). p. 7. The Life Saving Service would be added in 1914.

-

At least as characterized in T.E. Appleton, Usque ad Mare: A History of the Canadian Coast Guard and Marine Services, (Department of Transport, Ottawa, 1968), p. 80. The 396 tonne Vigilant was built by Polson Iron Works Ltd, Toronto, in 1904 and was armed with four small quick firing guns.

-

O.M. Meehan, “The Canadian Hydrographic Service: From the time of its inception in 1883 to the end of the Second World War”, (W. Glover and D. Gray [Eds.]), The Northern Mariner/Le Marin du Nord, Vol XIV, No.1 (January 2004), pp 1 – 158. Lillooet, built in Esquimalt by the British Columbia Marine Railway Company in 1908, was joined by a near-sister ship, the 522 tonne steamer C.G.S Cartier, which arrived at Québec 6 May 1910, from her builders in Great Britain, two days after the birth of the Navy.

-

The Wireless Telegraph branch did not have any dedicated ships but they did operate some nine wireless stations on the West Coast and thirteen on the East Coast and noted the existence of ten Marine and Fisheries steamers equipped with wireless transmitters which were available for message relay as required. These stations would prove to be a very useful asset in the world war to come.

-

The wreck of the SS Asia in Georgian Bay 14 September 1882, with a heavy loss of life, created the necessary stimulus. The RN, under Lieutenant H.W. Bayfield, RN, had surveyed the deep waters of the Great Lakes during the early 19th Century but the inshore waters (which were typically considered unsafe for navigation by sailing vessels) had not been adequately considered. Once steam vessels started using the more shallow waters, a new requirement for charts for inshore waters emerged.

-

Report of the Department of the Naval Service for the Fiscal Year ended March 31 1914 – Sessional Paper No 38, (Ottawa, King’s Printer, 1915).

-

The nephew of S.W Bartlett who had served with the Hudson`s Bay survey. Both Newfoundlanders were veterans of arctic navigation, having supported one of Peary`s expeditions. Appleton, p. 258. Karluk is an Aleut word for fish.

-

The reaction of the crew to the state of the ship is described in some detail in R.J. Diubaldo, Stefansson and the Canadian Arctic; (Montreal and Kingston, McGill-Queen’s Press, 1999).

-

From Captain Bartlett`s diary as quoted in Report of the Department of the Naval Service for the Fiscal Year ended March 31 1915 – Sessional Paper No 38, (Ottawa, King’s Printer, 1915). Herald Island lies just to the east of Wrangel Island north of Siberia.

-

Of the 17 who made it to Wrangel Island, 14 lived. Based upon their extended stay on the otherwise-uninhabited island north of allied Russia, Stefansson wanted to claim the island for Canada – which prudently declined the honour. In 1921, he planned another expedition to the island to claim it for Britain – which resulted in an international incident, and the death of most of the participants.

-

The progress of the expedition was reported annually in much more detail than the activities of the rest of the Department in most of its reports in the 1913 – 1919 time frame. A summary report is provided in Report of the Department of the Naval Service for the Fiscal Year ended March 31 191 – Sessional Paper No 38, (Ottawa, King’s Printer, 191). pp.36 – 40 and appendices

-

in Report of the Department of the Naval Service for the Fiscal Year ended March 31 1916 – Sessional Paper No 38, (Ottawa, King’s Printer, 1916), p. x

-

Department of the Naval Service, “Canadian Fisheries Expedition, 1914 – 1915: Investigations in the Gulf of St Lawrence and Atlantic Waters of Canada, under the direction of Dr Johan Hjort, Head of the Expedition, Director of Fisheries for Norway,” (Ottawa, J De Labroquerie Taché, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1919).

-

H.B. Hachey, ``History of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada``, (Ottawa, Fisheries Research Board of Canada Manuscript Report (Biological) No 843, 1965), p. 292

-

A. C. Hardy. `Dr Johan Hjort: 1869 – 1948`, Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society, Vol. 7, No. 19 (November, 1950), pp. 167-181. Hardy notes that Hjort’s “… series of reports on those [Canadian] waters were issued in a government 'blue book' with an absurdly small circulation; it is among the rarest and most prized of publications that an oceanographer can possess.”

-

Mark Tunnicliffe, “Ocean Acoustics in World War II – Dawn of a New Science in Canada,” in The Journal of Ocean Technology, Vol. 5, Special Issue 1, pp 1-12. (2010)

-

http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geography-boundary/boundary/continental-shelf/autonomous-underwater-vehicles/3879 consulted 13 March 2012, is a useful Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) summary of the project.