Military History

Library and Archives Canada PA-003399

Armoured trucks of the Motor Machine Gun Brigade during the advance from Arras, September 1918.

Measuring the Success of Canada's Wars: The Hundred Days Offensive as a Case Study

by Ryan Goldsworthy

Ryan Goldsworthy is a graduate of both the University of Toronto (Hons BA) and Queen’s University (MA). During his graduate education, he specialized in Canada’s combative role in the First World War. He has worked closely with a senior Royal Ontario Museum curator in the museum’s arms and armour collection. Currently, he is working as an editor of peer-reviewed articles at Queen’s, and he also serves in the position of ‘interpreter and special projects’ at the 48th Highlanders Regimental Museum in Toronto.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

During the final three months of the First World War, the Allies instigated a series of offensives against Germany on the Western Front which would be known as the Hundred Days Offensive. In this offensive, the Canadian Corps served as the spearhead for the British Empire, and effectively inflicted a series of decisive defeats upon the German Army. “Canada’s Hundred Days,” so-called because of Canada’s prominent and substantial role in victory, began on 8 August 1918 with the battle of Amiens, and carried through to the Battle of Mons on the date of the armistice, 11 November 1918. Although Canada was ultimately instrumental in achieving victory, since it defeated parts of 47 German divisions and cracked some of the most seemingly impenetrable German positions, the Canadian Corps suffered enormous losses. The Corps sustained over 45,000 casualties in a mere three months of fighting, which was not only its highest casualty rate of the entire war, but in the subsequent history of the Canadian military.1

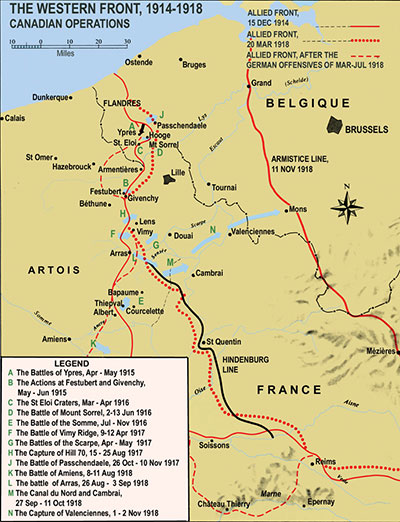

Directorate of History and Heritage

Map of Western Front 1914-1918

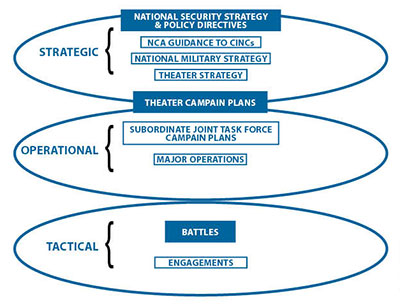

Traditionally, historians of Canada’s involvement in the Hundred Days have erred on the side of presenting the offensive as a highly successful, albeit costly campaign for the Corps. These studies, which have highlighted the success of the Hundred Days, have most often assessed the offensive from the tactical level alone, or the individual battles from the perspective of the Canadian Corps. However, in comprehensively evaluating the success of Canada’s Hundred Days, a three-tiered evaluation of success in the context of 1918 and its aftermath is essential. This is important because each level of war has its own measures of success, and military operations must therefore be analyzed for their successfulness based upon the parameters established at each of these unique levels. These three levels include the tactical, or the individual battles and engagements; the operational, or the theatre campaign plans and major operations; and finally the strategic, or the political direction of war, the national security and policy directives, and the national military strategy.2

US Army FM 9-6

Levels of war

These three basic definitions of the levels of military aims are based upon the model created by the modern Canadian Department of National Defence (DND), but, similar to any model, it is relatively rudimentary, not without its flaws, and should rather be used as a tool in grasping the concepts.

Through analyzing the success of the offensive by placing these three levels in the context of 1918 and its immediate aftermath, the most pressing question is how can ‘success’ be defined or measured. More specifically, who is it that determines what constituted successes in the context of the Hundred Days? To answer these questions of success, and to ultimately assess the offensive, this article will adapt the DND’s ‘levels of war’ model to include the measures of success established or implied by the key individuals of 1918 who occupied each of these three levels, including: Canadian Corps Commander Arthur Currie, Field-Marshal Douglas Haig, and Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden. In this study, these measures of success, and what these individuals were trying to achieve in the offensive, will be ‘fleshed out’ and analyzed. Subsequently, a more accurate evaluation of whether or not Canada’s Hundred Days can be considered a full success will surface. Ultimately, this article will argue that while on the tactical level, and to a lesser extent, the operational level, the offensive was successful, Canada’s Hundred Days was by and large a strategic failure. Moreover, this adapted model can be applied to any modern Canadian military conflict, such as that conducted in Afghanistan or Libya, in an attempt to comprehensively analyze its success.

Library and Archives Canada PA-002497

Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, February 1918.

Historiography

Much has been written about Canada’s Hundred Days by many highly respected Canadian scholars. Historian Bill Rawling offers perhaps the most succinct summary of the traditional historiography of the Hundred Days, concluding that the battles of the offensive have tended to be looked upon favourably by historians, mainly because of the way they ended – with victory.3 Similarly, Denis Winter contends that the last hundred days of the Great War have always been presented as a “triumphal march towards an inevitable victory.”4 In one of the seminal volumes of Canadian military history, The Military History of Canada,Desmond Morton assessed the offensive as the triumph that the “generals had prayed for.”5 Terry Copp also emphasized the tactical successes and “spectacular gains” of the Canadian Corps in 1918, espousing the popular argument that the Hundred Days determined the final outcome of the war.6 The study which perhaps comes closest to addressing the three levels of war in Canada’s Hundred Days is Shane Schreiber’s Shock Army of the British Empire. He argues that Currie may have been thinking beyond the tactical level, and concludes that Currie and the Corps straddled the “… imaginary and amorphous boundary between the tactical and operational level of war.”7

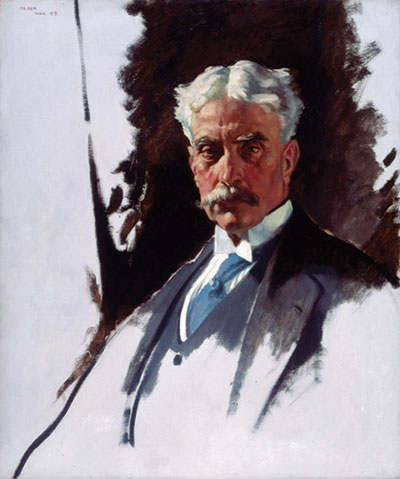

CWM-19710261-0394 painting by Harrington Mann

Lieutenant-General Sir Sam Hughes.

However, the most recent historiography has noted that these victories during the Hundred Days were not always accompanied by flawless logistics and tactics. In Shock Troops, Tim Cook admits that while Canada’s approach during the Hundred Days may have constituted the epitome of war fighting, many of the operations conducted during the campaign may have been “hurriedly and haphazardly planned.”8 In his expanded and even more recent study, The Madman and the Butcher, a comparative analysis of Sir Sam Hughes and Sir Arthur Currie, Cook effectively brings to light the sentiments of some of Currie’s contemporaries who were critical of the offensive’s casualties, and the purpose in engaging in combat from the second-to-last-day of the war.9=

In connection with the misgivings of Cook, and in a divergence from the traditional Hundred Days historiographies, British historian Tim Travers, in How the War was Won, is critical of both the operational and strategic doctrines of Haig and the armies under the British Expeditionary Force during the offensive.10 None of these studies, however, whether critical of the offensive or not, have comprehensively analyzed the success of Canada’s Hundred Days through each of the three levels of war, or through the measures of success established by the key individuals, Arthur Currie, Douglas Haig, and Robert Borden.

Arthur Currie – the Tactical Level

Although General Currie was always aiming to achieve battlefield victory, he gauged this success through various aspects – much more than the typical measures of ground, guns, and prisoners taken. In fact, the Canadian Corps never lost a battle in the final two years of the Great War, and based upon that statistic alone, the Corps was successful at the tactical level. Currie would come to view the last months of 1918 as the most significant achievement of the Canadian nation and the British war effort.11

However, by early-1918, the Canadian Corps was plagued by a state of administrative turmoil and uncertainty. The Canadian government wished to impose a 5th Canadian Division upon the Corps (under the command of the incompetent Garnet Hughes, son of Sir Sam Hughes), the BEF desired a reorganization of the corps both for “political effect”12 and to mirror British organization, and the four established Canadian divisions were not fighting together on the front. British command also aimed to integrate American battalions into the depleted Corps, which Currie predicted would be a complete disaster, and would destroy its “strong feelings of esprit de corps and comradeship.”13 Currie, quite naturally, was opposed to any measure which was not “in the best interests of Canada’s fighting forces.” 14

Library and Archives Canada PA-003287

Canadian transport moves across makeshift bridges constructed in the dry bed of the Canal du Nord.

Ultimately, Currie, with the aid of the Overseas Ministry, which afforded him the autonomy and support to achieve his goals,15 prevailed against all of these proposed changes, and kept the Canadian Corps fighting together for the entire offensive, which kept both its proven formations and its esprit de corps intact. Currie insisted that there was a direct correlation between tactical efficiency and unit organization, and organizational changes could just as easily impede rather than improve battlefield success.16 Currie’s view is supported by Desmond Morton, who contends that because of the tactics and circumstances of 1918, Currie’s insistence upon maintaining the structure of the Corps probably made his formation much more powerful in the series of offensive battles which filled the last three months of the war.17 The Corps benefited greatly from Currie’s efforts to keep it together, fighting together, and working together, and he ensured that divisions and brigades learned from each others’ successes and failures.18

Currie was also able to keep the Corps relatively independent from British command, and he instilled a sense of a national Canadian identity within it, to the point where, regardless of whether or not its personnel were British-born, the war “turned them into Canadians.”19 Tim Cook rendered his verdict upon Currie’s decisions on organization as having been “clearly right” and important to achieving success ‘at the sharp end.’20 Therefore, Currie’s measures of success, which included the maintenance of the formations, identity, and strength of the Canadian Corps, were all achieved.

CWM-19710261-0539 painting by Sir William Newenham Montague Orpen

Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie.

The next measure of military success from Currie’s perspective was the maintenance and aggrandizement of reputations. Although he was consistently focused upon perfecting the fighting capabilities of the Corps in 1918, he was also “highly cognizant” of how he and his men would be remembered in the annals of history, preparing for both the war on the ground, and the ensuing war of reputations.21 In terms of espousing the success of the Canadian Corps, Currie believed that it was the pre-eminent fighting force on the Western Front and he would not shy away from promoting this belief to anyone who would listen.21 These proclamations from Currie only strengthened the increasingly held opinion on the Western Front that the Canadian Corps was one of the most professional, reliable, and hard-hitting formations in France; its victories spoke for themselves. They became to be perceived as the ‘shock troops’ of the British Empire, and were inevitably, regardless of fatigue and previous sacrifices rendered, called upon to spearhead the Hundred Days. Although Currie achieved the heightening of the reputation of the Corps, many soldiers lamented the role, willing to trade their reputation for a reprieve in the reserve.23

Library and Archives Canada PA-003145

Canadian infantry advance under fire towards the Drocourt-Quéant Line, a heavily fortified series of German trenches.

By as early as late-1918, Currie was smarting from his belief that the British press and General Headquarters (GHQ) had downplayed the success of the Corps in the Hundred Days, and that the US propaganda machine was promoting an exaggerated account of the American role in the offensive. He responded to these issues with the creation of the Canadian War Narrative Section (CWNS) in December 1918. This historical section was established to maintain a sense of Canadian control on how the Hundred Days would be documented in print and presented to the public.24 Tim Cook argues that the report of the CWNS was not only an important step in recording and presenting the due credit of the Canadian Corps, but also in restoring Currie’s damaged reputation, which had been battered by Sam Hughes and his supporters in Parliament, who were enthusiastically accusing Currie of wasting Canadian lives and dubbing him a ‘butcher,’ and by some of his own soldiers, many of whom bought into the representation of Currie as a “butcher.”25

This element of casualty rates relates to the third, and arguably the most important measure of success for Currie at the tactical level – limiting casualties on the field. Arguably, Currie’s reputation as a butcher is unsubstantiated. His agony over casualty rates, his conscious attempts to minimize these numbers in battle, and the comparison of Canadian Corps casualty rates to the other formations on the Western Front indicate that Currie was as successful as possible in achieving his aims. Currie emotionally recorded that the most challenging element of his capacity was signing “the death warrant for a lot of splendid Canadian lives.”26 He was forced to accept the trade of the casualties for victory; it was the grim reality of war, and it was his role in it. This is perhaps best captured through his realistic statement: “You cannot meet and defeat in battle one-quarter of the German Army without suffering casualties.”27

Currie’s application of lessons learned28 from past offensives in an effort to abate casualties are quite clearly evident in the Corps’ casualty rates compared to other forces on the Western Front during the Hundred Days. For instance, in comparison with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during the Hundred Days period, the inexperienced Americans suffered an average of 2170 casualties per German Division defeated, while the Canadians accrued 975 per division defeated; the Americans advanced 34 miles and captured 16,000 prisoners, while the Canadians advanced 86 miles and captured 31,537 prisoners.29 Despite the fact that the AEF was six times the size of the Canadian Corps, Currie outstripped the AEF on every single tactical level. These numbers not only speak to the Canadian Corps’ greater experience and effectiveness on the battlefield compared to the Americans, but also to Currie’s efforts and consequent accomplishment to achieve great tactical success while minimizing casualties.

What also characterised the Corps under Currie was a determination to use the maximum allotment of material in the hope that it would save lives and win objectives.30 During the Hundred Days, Currie would refuse to engage without proper logistical support, as well as artillery support. At Cambrai, for instance, Currie insisted upon delaying combat until he had acquired adequate logistical support, undoubtedly sparing hundreds or thousands of Canadian lives.31 Bill Rawling, although sceptical that heavy artillery saved more lives, argues that by at least attempting heavy, strategic bombardments, Currie showed that he did not consider massive casualties to be a necessary price for victory.32 Shane Schreiber notes more forcefully that Currie ensured that during the offensive, the Corps “… paid the price of victory in shells, not in life.”33

In sum, Arthur Currie’s determinants of success included the upholding of the strength, unity, and organization of the Canadian Corps, advocating and ensuring the reputations and honours bestowed upon the Corps, and limiting casualties through planning, learning from mistakes, and through the generous expenditure of war material. In each of these tactical aspects, Currie was successful.

Library and Archives Canada PA-003277

French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (fourth from left) in discussion with Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (fourth from right).

Douglas Haig – the Operational Level

By August 1918, neither the French nor the Americans were ready to commit to a long campaign, due to exhaustion and inexperience respectively, and it fell upon the BEF and its ‘colonial’ soldiers to spearhead the offensive. Field-Marshal Douglas Haig’s self-proclaimed albeit vague operational measure of success during the offensive was “… the defeat of the enemy by the combined Allied Armies [which] must always be regarded as the primary object...”34 The Allied offensive was launched as a response to the German’s Spring Offensive in March, and the Canadian and Australian Corps were meant to spearhead an assault by the Fourth Army with the objective of easing the pressure on the lateral line at Amiens. Historian Ian Brown has argued that Amiens was seen as a “complete operational success,” ushering in for the first time mobility on the Western Front, where Haig was then able to successfully shift the axis of the BEF’s thrust following the blow.35 Furthermore, the deep penetration of the Hindenburg Line in September precipitated Haig’s hoped for withdrawal of the enemy along the whole of the front, and all gains of the German Spring Offensive had effectively been reclaimed.36 Therefore, based upon the terms of Haig’s desired objectives at Amiens and the Hindenburg Line, and upon his overall objective in the Hundred Days, the first phases of the offensive were an operational success.

Library and Archives Canada PA-003280

Belts of barbed wire protecting the Hindenburg Line.

During the offensive, Haig and the BEF developed a new material-heavy operational offensive doctrine,37 and in October 1918 alone, the British expended 2,000,000 artillery shells, carried out in such a “… coordinated and skilful manner that it is not certain that any defensive positions could have withstood them.”38 Prior to the offensive, however, the British General Staff proposed that the new munitions programs would not be ready until June 1919. This, however, was contrary to Haig’s operational goal of an autumn 1918 victory and his material-heavy operational doctrine, and so, flush with success, he ignored the GHQ, stressed the need to continue, and ultimately forced the Germans to accept an armistice in lockstep with his desired timetable in November.39 Haig was successful in putting an end to the war in 1918 and in refusing to stall for the new munitions programs. Although at times at great expense of life was required, Haig’s operational objectives for the Hundred Days were achieved.

Where the operational level of the Hundred Days was arguably a failure, or at least flawed, was in managing and limiting casualty rates. Throughout the war, British command was often wasteful in attempting to achieve its objectives. This trend was continued into the beginning of the battle of Amiens, when, following the spectacular gains of the first day of combat, the hope of a significant breakthrough began rapidly to dissolve, and both Haig and Fourth Army Commander Henry Rawlinson refused to stop pressing forward. The second day at Amiens revealed confusion in the Allied command, which exacerbated the losses to the infantry, who were ordered forward with inadequate artillery and armoured support.40 To continue operations under such conditions would only result in staggering casualties, but battle was sustained for another costly two days, followed by several days more of intermittent fighting. In fact, the combat at Amiens did not let up until Currie and the Australian Corps Commander, John Monash, appealed to Haig to stop before their respective corps were “pounded to pieces.”41 Haig declared that his eventual stoppage at Amiens was because of his responsibility to his “government and fellow citizens in handling the British forces,”42 making it clear that he had at least begun to measure operational success with the management of casualties.

However, because of the Canadian Corps’ role as the spearhead, a role which Haig had assigned to the Canadians, and despite the great efforts made to abate casualties by Arthur Currie, the heavy losses continued for the relatively small 100,000-strong Canadian force throughout the offensive.43 The Allied command had not experienced breakthroughs and movements like this in the entire war, and thus elected to continue on with little preparation, less rest, and sometimes ignorance with respect to the human costs incurred ‘at the sharp end.’ These factors were the consequences of Haig’s operational doctrine in the offensive, which held that “… if we allow the enemy a period of quiet, he will recover and the ‘wearing out process’ must be [our strategy]” adding that “the enemy’s troops must be suffering more than ours...feeling that this is the beginning of the end for them.”44 Clearly, Haig was committed to the operational goal of a ‘short-term’ defeat of Germany.

Library and Archives Canada PA-003247

Canadian troops, viewed by German POWs, advancing towards Cambrai, September 1918.

Given the surrender and collapse of Russia in 1917, coupled with the mutinous state of the French Army, there was arguably a significant lack of political desire among the Allies to continue the war past 1918. Furthermore, if Germany had been allowed time to recover, then their ‘ Class of 1920’ would have added 450,000 new men by October (plus 70,000 ‘patched-up’ wounded per month), and 100 German divisions would be made available following a simple shortening of their line to the Meuse. The War Office expected that, by virtue of a combination of these changes to German forces on the front, by spring 1919, the Germans would have over a million fresh troops ready for action.45 There was also a lot of Allied intelligence reports which suggested that Germany still posed a formidable resistance and the capability for a counter-attack.46 Haig thus assessed correctly that Germany had to be defeated as quickly as possible, or another period of attrition could possibly commence. In a certain sense, Haig was arguably saving lives in the long-term by bringing an end to the war in the short-term.

From Haig’s perspective, Canadian casualties in the offensive were less of a political liability to him than British casualties. As Schreiber bluntly contends, Canadian casualties did not represent the same political threat to Haig’s continued career as commander of the BEF, because Haig answered to British voters through David Lloyd-George, and not to Canadian voters through Robert Borden, and he concludes that “… in the stark terms of political capital, Canadian lives were, for Haig, cheaper than British lives.”47 However, the importance of the Canadian Corps to Haig is not to be understated. Haig was unofficially warned by the British War Cabinet that if he did not achieve success with manageable losses on the Hindenburg Line, his position as commander-in-chief would be in jeopardy.48 The reality was that with each British casualty, domestic political pressure mounted in Britain for Haig’s removal. Haig relied heavily upon the Canadian Corps in the final push for victory, not simply because Canadian casualties were politically less ‘costly’ for him, but because the Corps was arguably the only combat formation on the Western Front capable of consistently delivering battlefield victory. Thus, although Haig used the Corps as the spearhead to achieve his operational objectives, often at great expense, he valued them as a resource “not to be squandered.”49

As a cursory notice, the Hundred Days was arguably proven to have been a success through the reality of the ultimate continuance of Haig’s military career. Simply, the ultimate lack of action by Haig’s superiors against him indicates that the operations in the final hundred days of the war (both by the measure of casualty rates and in battlefield victories) were being viewed by Haig’s superiors as successful. Through these ends, both in preserving his military career while facing substantial warnings, and in the unleashing of his shock troops to seize victory and ultimately end the war, Haig’s command was a success. Ultimately, while at the operational level the Hundred Days was a costly and arguably an unsustainable affair in the longer-term, Haig and the BEF were able to achieve, and ultimately sustain, their operational objectives by bringing the war to an end in 1918 through relentless pursuit and material-heavy doctrine, by preventing the creation of another attritional stalemate, and by arguably saving lives in the short-term.

Library and Archives Canada, Sir William Orpen Collection, acc. No. 1991-76-1

Sir Robert Borden, Prime Minister of Canada.

Robert Borden – the Strategic Level

Political historian John English has perhaps best captured the controversial legacy of Sir Robert Borden, telling us that: “[Borden was] author of disunity yet creator of independence, an expression of Canadian commitment but the deliverer of the young to the slaughter.”50

First, where Borden can be credited as having been successful in the offensive was in his attempts to advocate for Canada’s place in international affairs, its role in the British Empire, and also, in fostering a sense of Canadian nationhood. Ultimately, through his efforts in advocating a place for Canada in the peace negotiations at Versailles and at the League of Nations, Borden ensured that Canada’s sacrifices during the Hundred Days would not go unnoticed or unrewarded in the postwar world. It was Canada’s great military contributions in the war, arguably the most significant of which occurred in the final hundred days (what David Lloyd George called “enormous sacrifices”51), which gave Borden the credence and justification in lobbying for Canada’s autonomy and more independent role in the postwar period. In this, Frederic Soward, a soldier in the Canadian Corps and eventual historian, wrote with conviction: “It was Canadian blood which purchased the title deeds to Canadian autonomy in foreign affairs.”52 With respect to Borden’s role, former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney wrote that Borden was the “father of Canadian sovereignty,”53 and Desmond Morton and Jack Granatstein have even contended that the First World War, for Canada, was a successful war of independence.54 By all these accounts, Borden was successful.

During the Great War, unlike Britain, Canada actually had nationally defined war aims. Borden established Canada’s these aims relatively early in the war, aims which were rooted in legal moralism and aimed to punish the German “military aristocracy.” By 1918, shortly before the Hundred Days Offensive, Borden had elevated his aims in the context of the other Allies, contending that Britain was “… disinterested in reaching a decision to its duty,” while Canada was ready to fight, “… [to] the last cause as we understand it, for every reasonable safeguard against German aggression and for peace of the world.”55 In a very similar vein, during the summer of 1918, Borden resolutely proclaimed, “… the [war] must be settled now and Germany must learn her lesson once and for all.”56 Although Germany was defeated in 1918, and to this end Borden succeeded, it would be the character of Borden’s war aims and policies that dictated the extremely high sacrifice which would be paid by the Canadians in Flanders.

Despite the fact that Borden believed the war could continue for another costly two years,57 his position to “fight it out to the end,” regardless of the costs, never wavered. Simultaneously, Borden does not appear to have consulted with either Haig or Supreme Allied Commander Ferdinand Foch on their strategies for the offensive, which adhered to the “relentless pursuit” doctrine. In fact, Borden only learned of the offensive once the Canadian Corps was already engaged in combat at Amiens.58 Borden would therefore base the national strategies of war on his incorrect assumptions on the remaining duration and commitment to the war. Robert Craig Brown, perhaps the most detailed biographer of Borden, has suggested that Borden was perhaps “too earnest” and “too committed” to winning the war to see, as other Allied leaders had, the long-term consequences for Canada in the total defeat of Germany.59

In early September 1918, in one of his speeches, Borden stated: “The duty of a Prime Minister is to centre his effort upon that which chiefly concerns the welfare of his country.”60 Therefore, it is clear that the accountability to and responsibility for Canadian lives overseas was one of Borden’s primary concerns. However, despite Borden’s warning to Lloyd George not to repeat the costs of Passchendaele,61 Canadian casualty rates only worsened during the Hundred Days, and yet Borden never exerted any serious political pressure upon either the Overseas Ministry or the commanders on the front to curtail these numbers (unlike the British War Cabinet’s warnings to Haig).

Library and Archives Canada PA-003286

Canadians advancing through the rubble of Cambrai, October 1918.

Furthermore, the total size of the Canadian force, and also the method by which it was kept up to strength, was ultimately the responsibility of Borden and his colleagues; Borden continued to order enlistments and conscripts to the front in 1918 regardless of the weight of the casualties.62 Contextually, although conscription had been introduced approximately a year before the Hundred Days began, all those conscripted did not reach the front until at least when the offensive had begun, and thus, all the ‘conscript casualties’ occurred entirely during the offensive. Borden’s conscription policy, as argued by Jack Granatstein, was instrumental in supplying men to the ‘sharp end’ during the Hundred Days, and in allowing the Corps to function with great effectiveness and efficiency.63 Indeed, in this way, conscription was tactically and operationally a success. However, the more men were forced into service, the more they were placed into harm’s way, and the more the national war efforts became divided, particularly between French and English Canada. Even outside French Canada, as the casualties mounted during the conscription period of the war, the previously marginalized pacifist and anti-war movements in Canada began to find wider acceptance and substantial growth in the number of participants.64

If the blame for casualty rates rests somewhere, the burden rests largely at the highest level of policy – policy which was ultimately responsible for how many individuals would be sent overseas. In sum, although the nature of the tactical and operational doctrines during the Hundred Days may have engendered higher casualties, Currie, and, to a lesser extent Haig, had at least exerted efforts to reduce those casualties, while Borden, despite his concerns over the enormous amount of Canadian losses and his accountability to the welfare of the Canadian people, did not impose enough pressure or use any leverage to try and abate them.

Library and Archives Canada PA-002746

Sir Robert Borden and Sir Arthur Currie take the salute at an end-of-war parade.

Finally, the most rudimentary measure of success for a Prime Minister, and something that one is consistently attempting to achieve, is election or re-election. Robert Craig Brown has noted that by 1917, Borden was anxious to avoid any action which would excite party controversy.65 Borden’s loyalty to his party was also explicitly evident during the offensive itself, where he recalled several political concerns in his memoirs which consumed his mind during the period.66 Although Borden retired from politics in 1920, because of “overstrain and illness,”67 the Canadian federal election of 1921, (the first following the Great War), was ultimately a disaster for the Conservatives.68 The cyclical ebb and flow of party politics is almost inevitable, but the fortunes of the Conservative party were invariably afflicted by the repercussions of their wartime decisions in the immediate postwar period. Several historians have suggested that the historic defeat in the 1921 election can be attributed, not only to the divisive conscription crisis, but also to the huge losses (monetarily and in casualties) sustained in the final months of war; losses which were still fresh in the Canadian consciousness, and a factor in the nation’s slumping economy in 1921.69 Thus, in terms of preserving the strength of the Conservative Party and promoting a re-election for his successor, Borden failed in these aims.

CWM 19710261-0813, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum

The Return to Mons, by Inglis Sheldon Williams

Ultimately, the strategic level of Canada’s Hundred Days was not a complete failure. Robert Borden successfully advocated a more independent place for Canada in the world, and a more substantial role in its foreign affairs. He accomplished his goal of the defeat of Germany through victory in the First World War, and he was able to supply and support the Canadian Corps with fresh recruits during its most dire hour. However, his aggressive and overly-committed war policies led to a massive increase in Canadian casualties during the Hundred Days, and these casualties were met with no strategic effort or pressure to curtail them – unlike the efforts of Currie, and, to a lesser extent, Haig. Although conscription was tactically and operationally advantageous, conscription increased the likelihood of casualties and contributed to the shattering of national unity, and it hardened anti-war movements both inside and outside Quebec. Finally, the Conservative Party was virtually decimated in the immediate postwar period. By these standards, from Borden’s perspective, the strategic level of Canada’s Hundred Days, was largely a failure.

Conclusions

While Canada experienced a virtual ‘baptism by fire’ during the Great War, and subsequently earned a much more autonomous and independent place in the postwar world, the sacrifices made by the young nation were steep – none steeper than in the final three months of the war. The Hundred Days Offensive ultimately resulted in the successful conclusion of the war, and the Canadian Corps, as the spearhead, was arguably the largest single contributor to the successes of the offensive. Success in war, however, according to the standards of the military and of politics, must be gauged through three levels: tactical, operational, and strategic. Battles and campaigns are rarely completely successful, and while many military engagements may find success at one or more of the three levels of war, they may also simultaneously fail in others.

CWM 19710261-0085

Canadians Passing in Front of the Arc de Triomphe, Paris, during the great victory parade. Painting by Lieutenant Alfred Bastien.

Significantly, however, the methodology of the three levels is imperfect, and amongst the three, there is a reasonable amount of blurring and appropriation of issues and interests of the same concern, and also a degree of imprecision in neatly categorizing each level within its own boundaries. Historian Richard Swain has even noted that the labels of “strategic, operational and tactical levels in war are merely artificial intellectual constructs created by academics to fashion neat boundaries that actual practitioners of war cannot be concerned with and may not perceive.”70 However, the methodology of using levels, despite its shortcomings, serves as an apt tool in comprehensively assessing the success or failure of war.

Analyzing the comprehensive success of Canadian Forces operations has only become increasingly relevant in the 21st Century, particularly with consideration to the recently completed missions in Afghanistan and in Libya. In fact, in November 2011, Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared that the Canadian military mission in Libya was a “great military success.”71 The major question which remains after the Prime Minister’s comments is: what is the definition of and the criterion for a “great military success?” Applying the “levels of war” model used in this article to modern Canadian conflicts would require a simple interchange of the relevant key individuals of the era and the measures of success established by these individuals. In the case of the 2011 Canadian military intervention in Libya, for instance, the measures of success established by individuals such as Prime Minister Stephen Harper, NATO Secretary General Anders Rasmussen, and Lieutenant-General Charles Bouchard would aptly fit the assessment of this conflict. With these facts in mind, and with consideration to the difficulty in defining the term “great military success,” this model is perhaps a useful method for clarifying the term and in ultimately gauging the success or failure of any given modern military endeavour.

DND photo by Sergeant Ronald Duchesne.

Lieutenant-General (ret’d) Charlie Bouchard with Governor General David Johnston after General Bouchard was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada, 28 September 2012.

Ultimately, in terms of the conclusive offensive of the First World War from the perspective of the Canadian Corps, reviewing the measures of success, aims, and objectives established by Arthur Currie, Douglas Haig, and Robert Borden, at each of the three levels, reveals that while on the tactical, and, to a lesser extent, the operational level, Canada’s Hundred Days was successful. However, it was largely, but not completely, a strategic failure. By analyzing contemporaneous Canadian conflicts with the same model applied here to the Hundred Days, with consideration to key individuals at each level, a much fuller and accurate evaluation of whether or not success has been achieved may surface.

I would also like to offer an acknowledgement to RMC/Queen’s scholar and professor Allan English, who has given me great support and guidance during the process of writing this article.

~Ryan Goldsworthy

-

JL Granatstein, “Conscription in the Great War,” in Canada and the First World War, David Mackenzie (ed.), (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), p. 73.

-

Howard Coombs, “In the Wake of the Paradigm Shift: The Canadian Forces College and the Operational Level of War (1987-1995),”in the Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 11, No.2., at http://www.journal.dnd.ca/vol10/no2/05-coombs-eng.asp , accessed 11 November 2010.

-

Bill Rawling, “A Resource not to be Squandered”:The Canadian Corps on the 1918 Battlefield,” in Defining Victory: 1918, Chief of Army’s History Conference, Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey (eds.) (Canberra: Army History Unit, 1999), p. 11.

-

Denis Winter, Haig’s Command: A Reassessment (London: Penguin Group, 1991), p. 211.

-

Desmond Morton, Military History of Canada (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1985), p. 163.

-

Terry Copp, “The Military Effort 1914-1918,” in Canada and the First World War, David Mackenzie (ed.) (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), p. 56.

-

Shane Schreiber, Shock Army of the British Empire: The Canadian Corps in the Last 100 Days of the Great War (St. Catherines, ON: Vanwell Publishing, 1997), pp. 2-4.

-

Tim Cook, Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting in the Great War 1917-1918 (Toronto: Penguin Group, 2008), p. 498.

-

Tim Cook, The Madman and the Butcher: The Sensational Wars of Sam Hughes and General Arthur Currie (Toronto: Penguin Group, 2010).

-

Tim Travers, How the War was Won: Command and Technology in the British Army on the Western Front: 1917-1918 (London: Routledge, 1992).

-

Mark Osborne Humphries (ed.), Sir Arthur Currie: Diaries, Letters, and Reports to the Ministry 1917-1933 (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2008), p. 28.

-

A.M.J Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), p. 100.

-

For a comprehensive analysis of the Overseas Ministry’s contribution to Currie and the Hundred Days, see Desmond Morton, A Peculiar Kind of Politics: Canada’s Overseas Ministry in the First World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), pp. 155-179.

-

Desmond Morton, “Junior but Sovereign Allies: The Transformation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918,”in Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, No. 8 (October 1979), p. 64.

-

Tim Cook, Clio’s Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2006), pp. 27, 29.

-

Cook, Clio’s Warriors: Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars, p. 34.

-

Robert J. Sharpe, The Last Day, the Last Hour: The Currie Libel Trial (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), p. 26.

-

For some examples of Currie’s dedication to learning from past mistakes, see: John Swettenham, To Seize the Victory: The Canadian Corps in World War I (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1965),216; and Cook, Madman and the Butcher, 256.

-

EKG Sixsmith, Douglas Haig (London: LBS Publishers, 1976), p. 107.

-

Ian Malcolm Brown, British Logistics on the Western Front 1914-1919 (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1998), p. 197.

-

Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Command on the Western Front: The Military Career of Henry Rawlinson, 1914-1918 (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1992), p. 350.

-

Gerard J. De Groot, Douglas Haig 1861-1928 (Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 1988), p. 387.

-

John English, “Political Leadership in the First World War,” in Canada and the First World War, David Mackenzie (ed.), (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), p. 78.

-

Martin Thornton, Sir Robert Borden: Canada (London: Haus Publishing, 2010), p. 59.

-

Desmond Morton and J.L. Granatstein, Marching to Armageddon.(Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1989).

-

Robert Craig Brown, “Sir Robert Borden, The Great War and Anglo-Canadian relations,” in Character and Circumstance: Essays in Honour of Donald Grant Creighton, John S. Moir (ed.), (Toronto: Macmillan, 1970), p. 204.

-

Robert Borden, Robert Laird Borden: His Memoirs II (Toronto: Macmillan, 1938), p. 854.

-

Thomas Socknat, Witness against War: Pacifism in Canada, 1900-1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987).

-

Frederic Soward,. Robert Borden and Canada’s External Policy 1911-1920 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1941),p. 81.

-

The Conservative party was ultimately disbanded in 1942, before being reformed. See: Terrence Crowley and Rae Murphy, The Essentials of Canadian History: Canada Since 1867 (New York: Research and Education Association, 1993), pp. 55-56.

-

For instance, see John English, Robert Borden: His Life and World (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1977); J.M Beck, Pendulum of Power: Canada’s Federal Elections (Scarborough, ON: Prentice Hall of Canada, 1968), pp. 150-168; and Cowley and Murphy, p. 35.

-

The Canadian Press, “Harper hails Libya mission as ‘great military success,’” In The Globe and Mail, 24 November 2011.