Commentary

DND photo IS2013-1007-04 by Sergeant Matthew McGregor

A Canadian Forces CC-177 Globemaster III aircraft is refuelled in the moonlight at the airport in Bamako, Mali, 25 January 2013.

What are the Forces to do?

by Martin Shadwick

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

One of the distressing consequences of the current political, bureaucratic, military, media, academic, and public preoccupation with the swampy vagaries of Canadian defence procurement—both the process as a whole and specific procurement initiatives (most notably, but not exclusively, a new fighter aircraft)—has, arguably, been some loss of collective focus on debating and defining Canada’s defence policy priorities in the post-Afghanistan era. What are the Forces to do in the coming years? What defence priorities will command the broadest possible political and public support? What are the prospects for the profession of arms in Canada? How much are Canadians prepared to pay for their security insurance premium? Where does Canadian defence policy go in particularly tough economic times, and in an unpredictable geo-strategic environment in which the flagship Canadian military activity of the past decade, the operation in Afghanistan, encountered increasingly tepid levels of public support in its later years?

This is not to suggest that Canada’s contemporary armed forces confront a crisis of confidence or crisis of relevance identical to those experienced in the late-1960s and early -1970s during the period of East-West détente, or, to lesser degree, during the early post-Cold War period. The relatively relaxed Canadian approach to security and defence that characterized the détente era, for example, is neither prudent nor politically tenable in the post-9/11 era. That said, there are similarities between the Canadian defence policy-making environment of 2013 and that of the détente era. In the latter, the Trudeau government was less than enamoured with Canada’s commitments to NATO or to United Nations peacekeeping. In 2013, Canada’s diminishing links with NATO have been further eroded by withdrawal from AWACS and AGS, and buffeted by differences over NATO’s potential role in the Arctic. Canada’s participation in United Nations peacekeeping operations has reached a very low ebb. With two traditional pillars of Canadian foreign and defence policy either undermined or unpopular, the Trudeau government (and some military denizens of Ottawa) sought to re-balance Canada’s defence priorities and bolster the perceived relevance of the armed forces by embracing an expanded range of quasi-military (i.e., surveillance and control, internal security) and non-military (i.e., disaster relief, search and rescue) commitments. Might Ottawa be tempted to play the same card today?

Born into an era of détente, the Trudeau government argued that a more benign geo-strategic environment permitted massive reductions in Canadian defence spending, manpower, and equipment—particularly that related to NATO commitments. UN peacekeeping was also de-emphasized in Trudeau’s 1971 white paper. NORAD essentially ‘broke even,’ but seemingly, the only ‘winner’ in the new defence policy was “… the surveillance of our own territory and coastlines, i.e. the protection of our sovereignty,” a priority that included aid of the civil power (particularly topical because of the October crisis of 1970), and a growing array of quasi-military and non-military responsibilities. “Although maintained primarily for purposes of sovereignty and security,” noted the white paper, “the Department of National Defence provides an important reservoir of skills and capabilities which in the past has been drawn upon, and which in the future can be increasingly drawn upon, to contribute to the social and economic development of Canada.” Overseas, the military “can also give further support to foreign policy objectives through increased assistance in economic aid programs. National Defence has capabilities to assist in such fields as engineering and construction, logistics policies, trades and technical training, advisory services, project analysis and air transport.”

DND photo CXC-81-2519

A CF CS2F Tracker flyingover Comox Valley, British Columbia,

21 August 1981.

The white paper positively dripped with references to non-military and quasi-military tasks, including Arctic surveillance, northern development, ice reconnaissance, surveillance of mineral exploration and exploitation projects, coastal and fisheries protection (thereby rescuing the previously doomed Tracker fleet), disaster relief at home and abroad, search and rescue (SAR), internal security, and, more broadly, “the protection of our sovereignty” against challenges which were “mainly non-military in character.” Ottawa also indicated, in other statements, that the proposed Long-Range Patrol Aircraft, the intended successor to the Argus anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft, might emerge with a comparatively modest ASW suite, but a broad spectrum of civilian-oriented remote sensing equipment. Having thus ‘uncorked the non-military and quasi-military bottle,’ Ottawa was soon receiving pitches for a DND-operated fleet of Canadair CL-215 water-bombers, provincial highway construction (military engineers were already labouring on civilian bridge and airfield construction in the North), and, from the academic and scientific communities, the creation of a military-operated logistical and support hub for civilian scientific research in the Arctic. Professor T.C. Willett of Queen’s University added a plethora of potential projects, including participation in the “planning, reconnaissance, and initial development of new community and town projects, particularly in the north and other as yet undeveloped parts of the country,” provision “of all air services for non-commercial public purposes” including “police work, ambulance, [and] rescue;” and the “provision and manning of social development teams to work with the native peoples all over Canada.”

The white paper did not prescribe a constabulary military—indeed, it declared an intention “to maintain within feasible limits a general purpose combat capability”—but its apparent zeal for non-military and quasi-military roles helped to fuel concerns that Canada’s armed forces were headed for constabulary status. This, in turn, prompted a debate over the nature of Canadian military professionalism. Colin S. Gray, writing in a 1973 Wellesley Paper, opined that a “military traditionalist sees the domestic orientation of [the white paper] as a temporary fad, dangerous to the national security, and/or as the possible harbinger of the ultimate demise of the military profession.” A modernist shares the traditionalist’s assumption that Canada needs armed forces, but “perceives that the armed forces must not merely be more obviously relevant to Canada’s needs than they have been in the recent past, but—still more important perhaps—they must be seen to be more relevant.” “Our modernist,” notes Gray, “has sought and found an impressive array of new or re-emphasized roles,” thereby demonstrating “how inventive a bureaucracy can be when it feels challenged to come up with something that is politically palatable.” Gray also noted, correctly, that “the armed forces would seem to be realizing, slowly, that there are really not that many tasks they can undertake in their efforts to assist the civil authorities without poaching on the preserves of civilian agencies” (or, one might add for contemporary consumption, the private sector). DND also came to realize that over-selling quasi-military and non-military roles could erode the case for a credible military capacity. Help, however, was at hand.

In 1975, the Trudeau government’s Defence Structure Review restored NATO to its pre-eminent position in Canadian defence policy and rescued the Canadian Forces from both the financial wilderness and the risk of “constabularization.” The product of a less benign strategic environment and entreaties from allies, the DSR heralded a major increase in defence spending, and a massive rebuilding of Canada’s military capabilities. Some of this funding trickled into the quasi-military and non-military sphere (i.e., additional SAR helicopters), but it was telling that the LRPA—the Aurora—emerged as the world’s foremost ASW aircraft and never did receive its civilian remote sensing suite. Similarly, DND’s interest in the Arctic quickly waned.

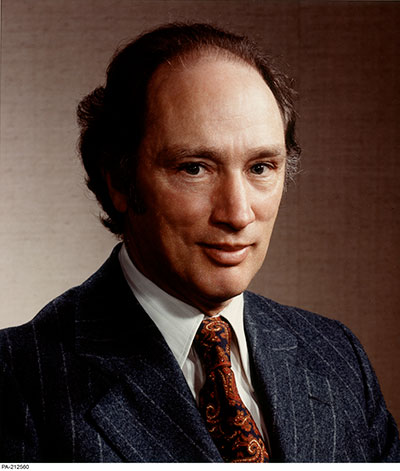

Library and Archives Canada PA-212560

The Right Honourable Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada.

Other than the normal platitudes about the need for inter-departmental cooperation and the relevance of the armed forces to such tasks as disaster relief, the white papers or major policy statements of 1987, 1994, 2005, and 2008 have, for the most part, devoted comparatively modest attention to non-military and quasi-military tasks. There have, however, been some interesting twists and turns. The Mulroney government’s 1987 white paper, for example, differed from its 1971 predecessor in viewing sovereignty protection through a holistic military, quasi-military and non-military lens. A manifestation of this approach was the plan to re-engine and update the Tracker, but the project was cancelled in the budget of April 1989 and the air force’s coastal patrol mandate summarily transferred to the private sector. The decision was attributed to financial pressures and the “non-military” role of the Tracker—others pointed to the political ideology behind alternative service delivery, industry lobbying and the need to remove a key rationale for the retention of CFB Summerside—but the net result was the loss of almost all of the air force’s fisheries patrol mandate. Barely 15 months later, the government again reversed course by announcing that the air force would re-enter the coastal patrol business, initially with a trio of recycled Challengers. The volte face, which left the private sector as the major provider, was consistent with the government’s slim 1992 statement on defence, a document rich in references to non-military and quasi-military tasks. Did this document reflect a sincere belief in the importance of new, post-Cold War paradigms of security, or did it reflect a bureaucratic and military survival strategy at a time when the post-Cold War future of the Canadian Forces was particularly uncertain?

The Chretien white paper of 1994 stoutly defended the need for a “multi-purpose, combat-capable” defence establishment, and rejected a constabulary model based upon non-military and quasi-military roles: “Over the past 80 years, more than 100,000 Canadians have died, fighting alongside our allies for common values. For us now to leave combat roles to others would mean abandoning this commitment to help defend commonly accepted principles of state behaviour. In short, by opting for a constabulary force—that is, one not designed to make a genuine contribution in combat—we would be sending a very clear message about the depth of our commitment to our allies and our values, one that would betray our history and diminish our future.” Such a ringing (if underfunded?) declaration was absent from Martin’s International Policy Statement of 2005, but its post-9/11 attention to homeland defence appeared to offer some potential, if ill-defined, synergies between assorted military, quasi-military and non-military tasks. On the international stage, the same could potentially be said of its treatment of the three-block war doctrine. The Harper government’s Canada First Defence Strategy of 2008 was similarly sparse in its discussion of non-military and quasi-military tasks, but several—including disaster relief—appeared on its list of the six “core missions” of the Canadian Forces.

DND photo IS2012-2003-144 by Master Corporal Marc-Andre Gaudreault

A Royal Canadian Air Force CP-140 Aurora aircraft from 14 Wing Greenwood, Nova Scotia, lands at Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, 23 July 2012.

Five years after the release of its Canada First Defence Strategy, might the Harper government ponder increased attention to non-military and quasi-military tasks? The answer is potentially complex. In the early Trudeau years, non-military and quasi-military tasks represented a lifeline of relevance at a time when NATO’s perceived utility had been reduced by détente and peacekeeping’s cachet had been eroded by Egypt’s expulsion of the United Nations Emergency Force in 1967. Today’s decision-making environment is different. Indeed, the Canadian Forces have been astonishingly busy—across the full spectrum of military, quasi-military and non-military operations, both at home and abroad—since the end of the Cold War. Canadians may not always agree with the tasks and missions assigned to their armed forces, but no one can argue that military personnel have been simply sitting around since the demise of the Soviet Union. That said, public support for latter-day Afghanistans is, to say the least, muted, the prospects for future peacekeeping, peace-enforcement, human security, and Responsibility to Protect missions remains unpredictable (as does, in some cases, Canada’s acceptability as a contributor), and NATO’s utility as a makeweight on the list of Canadian defence commitments remains suspect. It is also salient to note that public opinion polling continues to show very high levels of support for such non-military and quasi-military tasks as Arctic and coastal surveillance, disaster relief, and search and rescue.

Therein rest some problems. The Harper government has made much of its interest—a highly commendable interest—in Arctic sovereignty and security, but its plans for an expanded military presence in the north have been alarmingly descoped and repeatedly delayed. Previous governments, meanwhile, have made it difficult to move forward with an enhanced military role in such flagship areas as fisheries protection and search and rescue. The Mulroney government privatized the vast bulk of the air force’s fisheries surveillance role (the trio of recycled Challengers did not last long) and the Chretien government privatized the maintenance of the Cormorant search and rescue helicopters. Ousting private contractors, even when there are compelling reasons of broader national interest, is not for the faint of heart (and may, in any event, conflict with the Harper’s government’s political ideologies).The search and rescue picture will become even messier if maintenance of the proposed fixed-wing search and rescue aircraft is privatized—and a complete loss to DND if search and rescue as a whole is ever privatized. Even capital projects that can holistically supplement their core military raison d’etre with secondary or tertiary quasi-military and non-military capabilities are at risk. The utility of the Joint Support Ship for such roles as disaster relief, or as a pollution control headquarters ship, continues to decline in the face of fiscal constraint.

DND photo IS2006-7002-01a by Master Corporal Kevin Paul.

A CH-149 Cormorant on a SAR training mission.

Should the Harper government opt to revitalize the non-military and quasi-military roles of the Canadian Forces, it must choose carefully and holistically, and not undermine the fundamental military raison d’etre of the Canadian Forces. Excessive or ill-considered non-military and quasi-military responsibilities would threaten the core combat capabilities, the military professionalism, and the military ethos of the Canadian Forces, promote the undesirable ‘civilianization’ of the military, generate unrealistic public expectations, and invite jurisdictional and cost-effectiveness disputes with other government departments, as well as the private sector. A purely constabulary military establishment is not the type of military establishment that Canada requires in an era of disturbing geo-strategic uncertainty.

That said, non-military and quasi-military tasks, if selected with care, and with a holistic, finely-honed grasp of the broader national interest, can enhance military professionalism, and contribute, directly, or at least indirectly, to the preservation of the core combat capabilities of the Canadian Forces. To those who would reduce, jettison, transfer or privatize the non-military and quasi-military tasks of the Canadian Forces—or fail to re-acquire elements of some previous tasks—one could argue that such measures would: (a) be inconsistent with new definitions and paradigms of security, sovereignty and service to the state, both post-Cold War and post-9/11; (b) erode the nation’s already much diminished stock of multi-purpose, combat-relevant assets, capabilities, and expertise; (c) forego potentially attractive, and cost-effective, synergies between the military, quasi-military, and non-military responsibilities of the Canadian Forces; (d) eliminate demanding and challenging tasks that enhance, rather than diminish, military professionalism and the military ethos; (e) inflict significant damage upon military morale and the military’s self-image; (f) contribute, in a grim irony, to the undesirable ‘civilianization’ of the armed forces by fostering new and deeper linkages between military and civilian (i.e., contractor) personnel; and (f) contribute to the isolation of the Canadian Forces from the Canadian public.

It is right and proper to ask if a military institution can survive if it performs too many non-military and quasi-military tasks, but it is equally right and proper to ask if a military institution can survive if it eschews—or is forced by alternative service delivery-addicted and lobbyist-influenced governments to eschew—such tasks. Too often in Canada have we pondered the former while ignoring the latter.

Martin Shadwick teaches Canadian defence policy at York University. He is a former editor of Canadian Defence Quarterly.