MILITARY EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

DND/CFLRS Multimedia Production Centre

Senior Non-Commissioned Members in class.

What Education Should Non Commissioned Members Receive?

by Maxime Rondeau and Lisa Tanguay1

Maxime Rondeau, M.Sc. (political science), and Lisa Tanguay, M.A. (history), have taught at the Non-Commissioned Member Professional Development Division (formerly the Non-Commissioned Member Professional Development Centre) of the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School since 2005. They have each worked on developing training plans for the Centre’s programs and have participated in numerous working groups on the professional development of non-commissioned members.

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Introduction

Non-commissioned members (NCMs) of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), as explained in the first edition of the doctrine manual Duty with Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada (hereinafter referred to as Duty with Honour), are an integral part of the Canadian profession of arms.2 The publication of Duty with Honour was part of an institutional process that has been well documented, particularly in this journal. The catalyst of the process was the Somalia Affair, but the end of the Cold War and Canadians’ changing expectations of their armed forces were also significant factors.3 To respond to those challenges, numerous studies were conducted in the 1990s, which concluded that a reform of military ethos and leadership in the CAF was essential. An in-depth review of the Canadian Forces Professional Development System (CFPDS) was identified as a tool that could facilitate that reform.4 That said, the reflection associated with the review of the CFPDS has largely focused upon the needs of the officer corps.5

As teachers at the Non-Commissioned Member Professional Development Division (NCMPDD) at the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School (CFLRS), we feel that the institutional reflection on NCM professional development (NCM PD) is incomplete, and that is at the root of the substandard implementation of its strategic vision, as evidenced by the ambiguity surrounding the aim of NCM PD and the difficulties related to the operationalization of the educational dimension of NCM PD. We feel that the implementation of this vision would benefit greatly from better coordinated action on the part of the stakeholders and parties involved.6 Consequently, in this article, we propose a vision of the NCMPDD as a forum—both physical and intellectual—for the achievement of unifying projects, which would be beneficial to NCM PD stakeholders and the CAF organization as a whole, especially in a context of increasingly scarce resources.

The first section of this article is a brief overview of the concept of professional development (PD) in the CAF and what it means for NCM PD. The second section examines the causes of the incomplete reflection upon NCM PD. The third section focuses upon the observable consequences of the incomplete reflection and the possible solutions. The last part of this article discusses the unique contribution that the NCMPDD—which was known until very recently as the Non-Commissioned Member Professional Development Centre (NCMPDC ) and was part of the Canadian Forces College—can make to the community of stakeholders and parties interested in NCM PD in the implementation of these solutions.

Professional development and the role of the NCMPDD

The CAF’s effectiveness relies largely upon the quality of its training and education system.7 As such, most CAF members, from the time of their enrolment, take part in an ongoing PD process.8 The Canadian Armed Forces Individual Training and Education System (CFITES) defines this as a “comprehensive, integrated and sequential development process that constitutes a continuous learning environment” and consists of the pillars of training, education, self-development and work experience. Therefore, the aim of PD is to prepare CAF members for the escalating requirements of their careers and ensure adherence to the performance criteria set out in the military employment structure.9

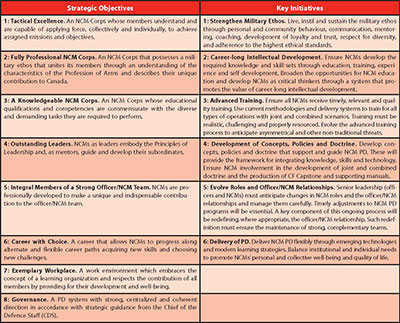

The Canadian Forces Professional Development System Document ~ Version 34

The Canadian Forces Professional Development System (CFPDS).

The above figure, taken from the CFITES interim guidance, shows how the CFPDS curriculum is provided through different pillars on an ordered, progressive basis.10 The NCMPDD focuses on the training pillar using topics such as operational planning and education, and the contemporary security environment. CFITES defines education as “the provision of a base of knowledge and intellectual skills upon which information can be correctly interpreted and sound judgment exercised,” and training as “the provision of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required in the performance of specific tasks.”11 In both cases, the issue is learning of varying complexity.

The document containing a detailed analysis of and a roll-out strategy for the NCM Corps 2020 project (hereinafter referred to as NCM 2020) summarizes the essential points of the motivation behind the implementation of NCM PD in 2003, i.e., the creation of a centre of excellence to allow for the implementation of key initiatives to attain specific strategic objectives.12 This centre, which has become the NCMPDD, has, since its creation, provided continuous and sequential learning programs that are common to all senior NCMs and organized according to the responsibilities of each rank.13 In Figure 1, the NCMPDD focuses its efforts upon approximately the top half of the pyramid, which represents Developmental Periods (DPs) 3 to 5.

NCM Corps 2020

The Objectives/Initiatives of NCM 2020.

In accordance with the leadership development framework (LDF), the NCMPDD curriculum participates in the development of the five meta-competencies related to the profession of arms and required by the context in which it is exercised: expertise, cognitive capacities, social capacities, change capacities, and professional ideology.14 The NCMPDD programs thereby ensure that most of the strategic objectives (SOs) that constitute the vision of the NCM corps in 2020 are attained, particularly SO 2, a professional NCM corps; SO 3, a knowledgeable NCM corps; and SO 4, outstanding leaders.15

Although the NCMPDD curriculum is not necessarily all that different from NCM PD offered in past decades, the specificity of its curriculum—and even that of NCM PD as a whole—can be seen in the wider range of topics covered and the significant revamp of its philosophy, and even its aim.16 An indicator of that revamp, in our opinion, is the growing emphasis upon education, acquisition of theoretical knowledge, and development of critical thinking skills, as opposed to instruction, training, and acquisition of specific technical skills. That statement is not meant to support the notion that instructional and training activities are less important in NCM PD. Rather, there is reason to believe that the environment in which the CAF operates requires a modification of the NCM PD vision. It is no coincidence that that modification has occurred at the same time as the integration of the NCM corps into the Canadian profession of arms.

In accordance with that integration, the NCM corps is required to possess abstract theoretical knowledge and to master complex skills.17 As the historian Allan English explains, Duty with Honour states that the fundamental differences between the NCM corps and the officer corps stem from their traditional responsibilities and expertise.18 For example, the officer corps has the authority to command and to decide when force will be used, whereas the NCM corps generally executes specific technical tasks that arise out of the decisions made by the officers.19 However, because of the uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity of the security environment in which the CAF operates, there is increasing overlap in the levels of conflict, and a growing number of responsibilities are being delegated to the junior levels. Consequently, NCMs are now engaged at the operational and strategic levels, and the distinction in terms of responsibilities and professional expertise has morphed into the requirement, for all members of the profession of arms, to demonstrate the critical thinking skills, creativity, and discernment necessary in the security environment of the 21st Century.20 Important from an institutional perspective, the integration of the NCM corps into the profession of arms involves numerous cultural changes, which are still in the process of occurring, and have contributed to the incomplete reflection upon NCM PD.

Origins of the incomplete reflection

In this section, we will examine three elements that we believe constitute the incomplete reflection on NCM PD: the incomplete research on NCM PD, the conceptual problems inherent to the documents that are supposed to guide the development of NCM PD, and, lastly, the ambiguity as to the aim of NCM PD itself. The analysis of those three elements will be used to fuel the discussion in the upcoming sections on the problems with implementing the NCM PD strategic vision and the possible solutions we would like to share with the community of stakeholders and parties interested in NCM PD.

In order for any strategic vision to be implemented, a series of obstacles, organizational and otherwise, must be overcome. Therefore, the information (i.e., all the qualitative and quantitative data) that is used to develop that vision, and the procedure for implementing it, are of utmost importance. However, we feel that the information pertaining to NCM PD is incomplete. The paltry amount of research devoted to NCMs—which is not just a CAF issue21—has had consequences on the CAF and NCM PD. Too often, institutional and academic research on the NCM corps is conducted as part of a larger reflection on the education and professionalization of the officer corps.22 As a case in point, NCM Corps 2020 is considered a “companion document” to Officership 2020, and the specific objectives described in Officership 2020 are incorporated into NCM Corps 2020.23 Although there may be logic behind that approach, the outcome is that the intrinsic value of NCM PD and its associated educational needs are rarely a subject of analysis as such. While there has been rather detailed and in-depth institutional reflection on officer education, fewer resources have been allocated to reflecting on the education of NCMs.24 Consequently, the objectives of NCM PD, particularly with regard to professional expertise, are not often enough based upon empirical research, as English recommends.25 In addition, this lack of information has led to a major issue at the operational level as to the organization of NCM PD.

DND photo

Cover image of NCM Corps 2020.

Based upon developments over the last decade, the CFPDS has been reorganized according to the responsibilities of the two corps, but there is still ambiguity as to the level of expertise required by each of the corps.26 For example, the expertise required of NCMs with regard to the general system of war and conflict is not clearly determined in Duty with Honour.27 Although the various levels of expertise required are set out in the Non-Commissioned Members General Specifications (NCMGS), the lack of clarity of some of the described tasks, and the interpretative nature of the LDF, do not provide clear strategic guidance as to the level of professional expertise required by the NCM corps.28 Although the conceptualization of the LDF was integrated into the CAF institutional leadership doctrine, and has been included in the NCMGS and the qualification standard (QS) for Developmental Periods 1 to 5, its ‘operationalization’ has yet to be developed. As we will see in the next section, that has direct consequences with respect to NCM PD. It should be noted that the LDF for officer professional development (OPD) is also incomplete. However, it could be argued that given the culture and structure of OPD, its educational dimension is less problematic than that of NCM PD. At a minimum, it would appear that the implementation of the OPD strategic vision can better adapt to the LDF in its current state. Indeed, that highlights the last element of the incomplete reflection on NCM PD: its aim.

NCM PD currently seems to be pursuing two objectives that are very different, though not necessarily incompatible. On the one hand, as evidenced by the requirements set out in NCM 2020, there is a desire to equip the NCM corps with specific tools, such as stronger ethos, critical thinking skills, communication skills, cultural intelligence, and so on. The logic behind that desire is solid, because it satisfies both the societal imperative and the functional imperative.29 On the other hand, there is a desire to provide PD opportunities to senior NCMs who are destined to be part of a command team.30> The underlying logic also stands to reason, as those NCMs must be able to communicate with the officers on the command team, master the professional jargon, and demonstrate specific skills enabling them to make effective recommendations. Nevertheless, those two objectives, although compatible, contribute to the ambiguity that characterizes NCM PD. In fact, the final result of an NCM’s progression through the NCM PD developmental periods (from basic qualification to the senior appointment program) has still not been clarified. Is the goal for the CPO1s/CWOs who will complete the senior appointment program to obtain a diploma? Would the proposed Professional Military Education Program for NCMs (NCM PMEP), similar to that of the second OPD developmental period (although that component is in a state of flux) but spread out over the five NCM PD developmental periods, support the succession planning process, and thereby help identify future members of the command teams? As long as those types of questions remain unanswered, it will be difficult to optimize implementation of the NCM PD strategic vision, because that could lead to already scarce resources being used unwisely, or for incompatible purposes. The next section addresses the practical consequences of the incomplete reflection on NCM PD.

CFLRS Multimedia Production Centre

Close-up of senior NCMs in class.

Consequences of the incomplete reflection

As teachers at the NCMPDD, we have observed strategic and operational consequences as a result of the incomplete reflection on NCM PD. At the strategic level, the recent publication of various guidance documents has undermined the optimization of NCM PD because of a lack of clear governance. At the operational level, the revision cycle of the documents that guide the development of NCM PD is impeding its implementation, particularly with regard to developing and updating the NCMPDD curriculum.

Strategic consequences

The modernization of CFITES opened the door to the NCM PD update and the formulation of new strategic guidance. Some of that guidance applies to the entire NCM corps, while other parts seem to apply to senior NCMs who are destined to participate in the succession planning process. Among the documents that are for all NCMs, the distribution of the NCM PD Modernization Plan, and the publication entitled Maintaining the Track: Benchmarking NCM Corps 2020 Progress (hereinafter referred to as Maintaining the Track) shed light upon the importance of assessing the attainment of the strategic objectives put forth in NCM 2020. On one hand, according to the NCM PD Modernization Plan, the NCM 2020 objectives have not yet been completely achieved, and the result is a growing gap between NCM PD and the need to develop the judgment and critical thinking skills required of NCMs in the contemporary operating environment.31 Similarly, the plan concludes that that NCM PD does not provide enough educational opportunities that foster the development of judgment and critical thinking skills.32 On the other hand, the authors of Maintaining the Track feel that progress has been made towards achieving the vision set out in NCM 2020, although much remains to be done, particularly to determine and describe NCMs’ educational requirements.33 We are sceptical of the claim that the gap is widening between NCM PD and the development of NCMs’ critical thinking skills; we have witnessed the gradual alignment of the programs given by the NCMPDD on the strategic objectives set out in NCM 2020. That said, we do acknowledge that some ambiguity remains as to the educational requirements for the NCM corps.

The conclusions drawn from those two documents are interesting, but they provide little information on the concrete accomplishment of the NCM 2020 strategic objectives. Despite its relevance, the study conducted by the Maintaining the Track team is qualitative and indicates the participants’ opinions but cannot be generalized to the NCM corps as a whole. The authors do not deny that; they acknowledge that even though the start-up phase indicated in the NCM 2020 detailed implementation plan ended in 2008, no formal assessment has been conducted thus far to determine the extent of the progress made to date.34

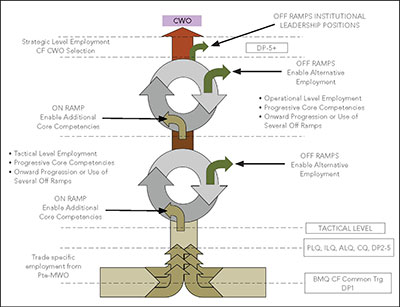

Beyond Transformation ~ The CPO1-CWO Strategic Employment Model

The Progressive Model.

Despite the absence of a formal and quantitative assessment, new strategic guidance, more specific to NCMs who are destined to participate in the succession planning process, has been added to that of the NCM 2020 vision. Beyond Transformation: The CPO1/CWO Strategic Employment Model (hereinafter referred to as The Strategic Employment Model) proposes to introduce a “Progressive Model for CPO1/CWO professional development from a graduated, flexible, and comprehensive perspective.”35

The document entitled Competencies Expected of Senior Appointments – The Strategic Chief36 (hereinafter referred to as The Strategic Chief) suggests a list of attributes which are required for the roles and responsibilities of CPO1s/CWOs who have obtained a senior appointment. Those publications provide valuable strategic guidance, but do not specify its integration into the current NCM PD scheme or the impact upon the achievement of the NCM 2020 vision.37 Moreover, the organizations responsible for PD delivery are given significant leeway:

As a recognized profession, the CAF has the ability to develop its own professional curriculum, standards and certification. Centres of excellence such as CMP, DLI, NCMPDC and CFC must develop specific education to better train NCMs to think critically and gain a more broad-based understanding of the strategic environment. These must not simply be modifications to Officer Curriculum, but rather focused, exclusive and tailored towards NCMs, while supportive of the Progressive Model.38

Moreover, the NCM PD Modernization Plan gave rise to the development of an NCM PMEP, still in the draft phase and inspired by the officer professional military education system. The NCM PMEP is partially aligned with the content of the NCMPDD programs and could influence NCM PD as a whole. However, in its current state, we do not know whether it is intended for the NCM corps as a whole, or just the senior NCMs selected to be members of a command team. In addition, one of the only manifestations of the NCM PMEP consists of the integration of some of its elements into the NCMGS. Therefore, it appears that the aim of the NCM PMEP has yet to be determined, in spite of the difficulties in finding common ground between the parties involved.

In sum, the CFITES modernization and the NCM PD update preceded the publication of strategic guidance documents without establishing a clear system of governance in order to determine the priority of strategic guidance. Moreover, all those directives influence the mandate and the activities of the NCMPDD without necessarily taking its operational realities into account.

DND photo

Cover image of Beyond Transformation.

Operational consequences

The development of the NCMPDD’s curriculum is part of the cycle of revision of a series of documents from the Canadian Defence Academy (CDA): the NCMGS, the QS, and training plans (TPs). However, the frequent and substantial revision of those documents do not seem to fit into a holistic and systematic scheme that takes the operational realities of the NCM PD delivery organizations and other interested parties into account. Also, the absence of a holistic system of development and the tempo at which those documents are revised undermine the delivery of NCM PD. Until very recently, the NCMPDD was responsible for the TPs, and therefore, in charge of carrying out the changes made in the NCMGS and the QS. The Division is supposed to take back that responsibility once the transition to CFLRS has been finalized. Notwithstanding questions of reorganization, the tempo of revision of the above-mentioned documents is difficult to maintain with the current resources. The NCMPDD has managed to qualify the required number of candidates in a year without making the changes imposed by the cycle of revision and development of the NCMGS, the QS, and the TPs. In addition, since the 2011 revision cycle, the documents that guide the development of NCM PD have been submitted to the interpretation of the LDF before it has even been ‘operationalized’ by CDA. Consequently, a multitude of questions regarding the practical application of the LDF in the development of curriculum have remained unanswered, thereby contributing to undermining NCM PD delivery. We believe that the curriculum revision and development cycles, like the development of strategic guidance, would benefit from greater coordination between the NCM PD stakeholders if they were anchored in the operational realities of the PD delivery organizations.

When considered individually, these strategic and operational issues do not threaten the quality of NCM PD in the short term. In this sense, the NCMPDD is fulfilling its mandate, as it is able to provide high-quality PD, based upon the NCM 2020 vision. However, at the strategic level, the absence of coordination among the various strategic guidance, along with the organizational problems regarding curriculum development, is preventing the optimization of that vision. A coordinated effort between the NCM PD stakeholders, and the centralization of the reflection on NCM PD and its delivery, could be contemplated as solutions. Cooperation among NCM PD stakeholders would facilitate the achievement of the new guidance set out in documents such as The Strategic Chief, and The Strategic Employment Model. The next section broaches the role that the NCMPDD could play in fully achieving the NCM 2020 vision.

An NCM PD centre of excellence

An opinion expressed by one of the respondents of the Maintaining the Track study was that the NCMPDD “is not equivalent in terms of status and credibility to the other CF colleges or US Army academies for NCOs.”39 Admittedly, a rallying point must be established to ensure the development of NCM PD’s strategic vision and governance. We believe that the NCMPDD can serve to centralize institutional reflection on NCM PD. Its contribution could be made at various levels. In addition to being a PD delivery organization, it can participate in developing the NCM PD strategic vision and produce empirical research on NCMs, thereby offering solutions to overcome the different operational and strategic problems.

Solutions to operational problems

First, we believe that the expertise acquired thus far by the NCMPDD can help NCM PD stakeholders solve operational problems. The NCMPDD’s expertise is wide-ranging. As the main NCM PD delivery vehicle, the Division and its diverse personnel (mentors, NCMs, civilian personnel) possess in-depth knowledge of the professional and operational realities of NCMs that is indispensable to the implementation of any NCM PD program. The Division also boasts expertise with respect to distance and in-class PD: various in-class and online teaching methods have been developed and improved since 2003. The NCMPDD personnel have been trained to provide high-quality instruction, and the lessons learned since 2003 are an important component of the Division’s corporate memory. The Division could thereby participate in systematizing a development process according to the experience acquired during the various phases of development and revision conducted thus far.

It would be beneficial for the institution to further build upon that expertise and allow greater flexibility to PD delivery establishments like the NCMPDD. The NCMGS are currently made up of a set of tasks identified under headings such as leadership. The level of precision of those tasks is such that it goes against the philosophy set out in the NCMGS standard, which aims to grant flexibility to the subject-matter experts working in PD organizations. Rather than formulating tasks using action verbs and specific conceptual notions (for example, “sustain the whole-of-government approach”), it would be indicated to give more latitude to PD delivery establishments, so that they could choose, on the one hand, the right learning taxonomy (the science of classification – Ed.), and, on the other hand, the appropriate concepts in accordance with the overarching topics selected by the establishment. That approach would ensure coherence in the taxonomic progression throughout the developmental periods and a continuous update of the concepts taught. In our opinion, it would be beneficial to give greater flexibility with regard to the guidance given in the documents that guide the development of NCM PD, while devoting more effort to the organization of the strategic vision concerning, for example, the aim of PD and the precedence of the strategic guidance. Moreover, the Division’s operational expertise could be extended at the strategic level.

Solutions to strategic problems

The NCMPDD leadership and teaching personnel have been delivering NCM PD since 2003, and they pore over NCM PD strategic guidance documents on a daily basis. We believe that the Division would be well placed to participate in the development of strategic guidance if it acquired, in addition to its operational expertise, institutional (i.e., academic) expertise on the NCM corps as a whole. That expertise could be acquired by developing research programs with the aim of collecting empirical data on the NCM corps and, more specifically, on senior NCMs.

Given the pool of candidates that it qualifies every year, and the diversity of its personnel, the NCMPDD would be the perfect choice to become a centre of research devoted to NCMs as a professional corps. Because of the number of candidates it qualifies annually, the Division could poll NCMs as a professional corps and conduct empirical research on each rank in order to better define the responsibilities and educational needs of every PD phase. Collecting empirical data would give rise to better familiarity in the CAF with the specific needs of the institution and its main NCM education organizations. Different platforms could be used to poll NCMs on a large scale during the distance learning phase of the programs, and the discussions of the study groups conducted during the in-house phase could serve to analyze more specific problems. That would help identify the educational requirements of the NCM corps and prevent a duplication of the officer education system. The NCMPDD could thereby participate in developing an education system just for NCMs that is based upon empirical data. Naturally, this institutional research would be conducted while taking into account the crucial link between the NCM corps and the officer corps, and the need to harmonize their respective PD systems to some extent. The NCMPDD’s previous affiliation with the Canadian Forces College is bound to facilitate the link between the NCM PD and OPD curriculums.

However, acquiring that expertise depends upon the interaction of NCMs with their instructors and teachers. Therefore, the quality of the relationship—virtual for the distance portion, and face-to-face for the in-class portion—is of utmost importance in an environment where collecting empirical data is an objective. We therefore believe that the establishment of a genuine centre of excellence goes hand-in-hand with the maintenance of courses offered in class and the interaction of candidates with qualified teachers and subject-matter experts. On that topic, for example, we feel that the abolition of the in-house course for CPO2s/MWOs should be reconsidered.

Centre of excellence, NCM school

Lastly, the NCMPDD’s credibility is also suffering from the absence of a clear identity and a sense of belonging. Since its creation in 2003, the NCMPDD has operated as part of a number of different organizations such as the Canadian Forces Learning and Development Centre, the Canadian Forces College, and, more recently, CFLRS. Without commenting on the NCMPDD’s affiliation with any one of those organizations, it is clear that such a frequent change of administration is symptomatic of a lack of identity that has likely resulted in the reflection on the education of NCMs being incomplete.

In conclusion, the NCMPDD’s identity could be strengthened if its mandate were expanded to include ensuring the centralization and governance of institutional reflection on NCM PD. If the Division participated in the development of concepts, strategic guidance, and research with respect to NCM PD, the NCMPDD would be in a position to become a genuine centre of excellence, and, in the long term, a leadership school able to acquire institutional expertise on NCMs as a professional corps.

Awareness of the roles and responsibilities of NCMs, and recognition of their integration in the profession of arms would be enhanced. Considered as the guardians of the NCM corps and co-managers of the profession of arms, CPO1s/CWOs could, through the NCMPDD, provide governance of a NCM PD system “with strong, centralized and coherent direction in accordance with strategic guidance from the Armed Forces Council.”40

We believe that by investing the necessary resources to centralize institutional reflection and empirical research in the NCMPDD, it would be possible to optimize the achievement of the NCM 2020 vision, while offering concrete solutions to problems that are currently undermining the effectiveness of the NCM PD system. Centralizing institutional reflection and research in the NCMPDD would facilitate the sharing of information and the acquisition of institutional expertise on the NCM corps, while strengthening, in practice, the learning organization concept and the governance of NCM PD.

RMC Saint-Jean Multimedia website

Aerial view of Royal Military College Saint-Jean which includes the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School.

NOTES

-

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Mélanie Paquette to the reflection that is at the root of this article, and to thank her for her comments on the current version. We would also like to thank Jean-François Marcoux and André Séguin for their comments.

-

Canadian Defence Academy – Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, Duty with Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada, (Kingston, ON: Department of National Defence, 2009).

-

See Bernd Horn, “An Absence of Honour: Somalia – The Spark that Started the Transformation of the Canadian Forces Officer Corps,” Allister MacIntyre and Karen D. Davis (Eds.), (Kingston, ON: Canadian Defence Academy Press, 2006), pp. 245–280, Dimensions of Military Leadership.

-

See the reports of the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to Somalia, Minister Young’s report and the reports of the Monitoring Committee on Change in the Department of National Defence.

-

See the 1995 report of the Officer Development Review Board, also known as the Morton Report, and the 1998 report presented to the RMC Board of Governors by the Withers’ Study Group entitled Balanced Excellence: Leading Canada’s Armed Forces in the New Millennium. The “Debrief the Leaders” project (officers), presented in 2001 by the Special Advisor to the CDS on PD, also provides a good idea of the resources and the reflection devoted to officer professional development.

-

These stakeholders include certain work cells of the Canadian Defence Academy, the Canadian Forces College, the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School, the Chief Force Development, and so on.

-

For a discussion of the concepts of education and training in a military context, see Kenneth Lawson, “The Concepts of Training and Education in a Military Context,” Michael D. Stephens (Ed.), (New York, St Martin’s Press, 1989), pp. 1–12, The Educating of Armies.

-

For a more in-depth discussion, see Ronald G. Haycock, “The Labours of the Athena and the Muses,” Gregory C. Kennedy and Keith Neilson (Eds.), (New York, Præger, 2002), pp. 167–196, Military Education: Past, Present, and Future; as well as Douglas L. Bland, Backbone of the Army: Non-Commissioned Officers in the Future Army, (Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999).

-

Canadian Forces Individual Training and Education System, Glossary (A-P9-050-000/PT-Z01).

-

Canadian Forces Individual Training and Education System, Interim Guidance.

-

Canadian Forces Individual Training and Education System, Glossary (A-P9-050-000/PT-Z01).

-

Chief of the Defence Staff, The Canadian Forces Non-Commissioned Member in the 21st Century: Detailed Analysis and Strategy for Launching Implementation (NCM Corps 2020), (Ottawa, 2002). [In particular, see pp. I-26, I-41, and I-42.]

-

In order to avoid a debate over nomenclature and for the purposes of this article, we consider individuals in the rank of PO1/WO to CPO1/CWO as being senior NCMs. See DAOD 5031-8 and the most recent NCMGS for the distribution in the Developmental Periods.

-

The Canadian Forces Professional Development System Document, pp. 15–16 and 20–21.

-

Chief of the Defence Staff, The Canadian Forces Non-Commissioned Member in the 21st Century: Detailed Analysis and Strategy for Launching Implementation (NCM Corps 2020), (Ottawa, 2002), p. I-29.

-

For example, in the mid-1980s, the senior NCO course also covered topics such as communication, management, and military leadership.

-

Allan English, The Senior NCO Corps and Professionalism: Where Do We Stand?, prepared for the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, 2005, p. 46.

-

See Guiseppe Caforio, “Trends and Evolution in the Military Profession,” Guiseppe Caforio (Ed.), (New York, Routledge, 2007), pp. 217–237, Social Science and the Military: An Interdisciplinary Overview.

-

For example, see Yves Tremblay et al., L’éducation et les militaires canadiens, (Montréal, Éditions Athéna, 2004).

-

Canadian Defence Academy, The Canadian Forces Professional Development System Document, Version 27, 11 March 2010, p. 8

-

A good example is the “Debrief the Leaders” project. Initially, the project was supposed to have an “officer” component and an “NCM” component. Only the “officer” component was published.

-

To understand the genesis of the concept of meta-competencies in the CAF, see Robert W. Walker, The Professional Development Framework: Generating Effectiveness in Canadian Forces Leadership, (Kingston, ON: Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, 2006). The concept has been repeated in a number of official publications, including Leading the Institution.

-

As discussed previously in this article, the societal imperative refers to the legitimacy of the CAF and the compatibility between the values of the institution with those of the parent society, Canadian society. The functional imperative refers to the organization’s ability to effectively conduct its missions. In both cases, NCM PD can be seen as a way to satisfy both imperatives.

-

For more on this subject, see the memorandum of February 2012 by the CF CWO, CPO1 Cléroux, entitled Competencies Expected of Senior Appointments – The Strategic Chief. Also of interest is “The Command Team: A Key Enabler” by CWO Stéphane Guy, published in the Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 2010, pp. 57–60, as well as “The Role of the Chief Warrant Officer within Operational Art” by CWO Kevin West, published in the Canadian Air Force Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2010, pp. 48–59. Also, a more critical perspective is available in the discussion on the command team in “The Command Team: A Valuable Evolution or Doctrinal Danger?” by Alan Okros, published in the Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2012, pp. 15–22.

-

Individual Training and Education Modernization Strategic Guidance – Annex B: Modernization of NCM Professional Development, p. B-1.

-

Directorate of Learning and Innovation, Maintaining the Track: Benchmarking NCM Corps 2020 Progress, (Kingston, ON: Canadian Defence Academy, 2011), pp. 4–5.

-

[Translation] “Although the 2008 deadline for the execution of the five-year “start-up” included in the NCM Corps 2020 detailed implementation plan has passed, no assessment has been conducted to determine the specific progress made,” Maintaining the Track, p. 9.

-

Chief of Force Development, Beyond Transformation: The CPO1/CWO Strategic Employment Model, (Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 2011), p. 29.

-

CPO1 Cléroux (CF CWO), Competencies Expected of Senior Appointments – The Strategic Chief, February 2012.

-

Beyond Transformation acknowledges that it is necessary to review the General Specifications (GS).

-

Beyond Transformation, p. 34. Please read “NCMPDD” in place of “NCMPDC .”