DIVERSITY

Credit: Canadian Forces Recruiting Group (CFRG) IMG_1324

Recruiting poster

Diversity Recruiting: It’s Time to Tip the Balance

by Chantal Fraser

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Lieutenant-Colonel (ret’d) Chantal Fraser, CD, MBA, served for 28 years in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF). In her last position as Senior Staff Officer Plans at the Canadian Defence Academy, she managed the CAF Aboriginal Programs, and worked closely with the Directorate of Human Rights and Diversity, and the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group, on topics related to Recruiting, Employment Equity, Personnel Generation, and Retention.

“Base your expectations not on what has happened in the past, but rather on what you desire for the future.”

~ Ralph Marston

Introduction

The Canadian military has a rich history with respect to diversity. English and French speaking Canadians and Aboriginal peoples have served in or with the Canadian military throughout our history. Black Canadians first served in the War of 1812. Women first served in uniform as nurses during the Northwest Rebellion in 1885. Chinese and Japanese Canadians have served since the early-1900s. Canadian Sikhs served in the First World War. Canada was one of the first nations to open all military occupations to women, along with Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway. The dress regulations have been adjusted to accommodate cultural and religious differences. For example, Aboriginal members may wear braids, and Muslim women may wear a hijab. Aboriginal peoples, women, and visible minority Canadian Armed Forces members have achieved the highest ranks: General Officer/Flag Officer and Chief Warrant/Petty Officer First Class.

For the last decade, the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group (CFRG) has met or exceeded the majority of the Strategic Intake Plan goals (recruiting goals set by occupation and environment).1 CFRG still has difficulty recruiting for some occupations, such as Pharmacist. Thousands of people apply to join the CAF each year, and many go away disappointed.

![female junior officer [foreground]](images/25-FRASER-image02.jpg)

Credit: CFRG op_m_17f

Female junior officer [foreground]

With our impressive history and the current level of interest in serving in the military, does it really matter if the CAF reflects Canadian population? Given the projected Canadian demographics,2 I contend that it does. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the face of Canada continues to change, and so must the CAF as it moves into the future and represents the face of the Canadian public it defends.

Canadian Demographics

Canada has an increasingly diverse population and work force. In 2009, women constituted more than half the available labour pool.3 In 2008, 62 percent of undergraduate degrees and 54 percent of graduate degrees were granted to women.4 These numbers are expected to continue to rise. Statistics Canada projects that by 2031, three out of ten young Canadians will be members of a visible minority group, less than two-thirds of Canadians will belong to a Christian religion, and 30 percent of our population will have a mother tongue other than English or French.5 Statistic Canada Census reports from 2001, 2006, and 2011 also show a downward trend of Canadians speaking English (56.9 percent) and French (21.3 percent) as their mother tongue.6 Those considered to be visible minorities have a higher propensity to complete post-secondary education in part due to the importance placed upon education by their families. The majority of the visible minority populations are concentrated in our three biggest cities, Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. Statistics Canada projects that by 2031, the Aboriginal population will be between 4 - 5.3 percent of the population, and that the average age of Aboriginal peoples will continue to be several years younger than that of the non-Aboriginal population.7 The percentage of Aboriginal peoples completing post-secondary education is growing, but is still significantly lower than that of the non-Aboriginal population.8 This is in part due to the lower percentage of Aboriginal peoples who complete high school. A large percentage of Aboriginal Canadians live in or near urban centres.

Credit: CFRG op_m_02f

Hercules pilot

What is Diversity?

The terms Diversity and Employment Equity (EE) are sometimes used interchangeably and often incorrectly. Diversity is much more inclusive than EE referring “… to people from a variety of backgrounds, origins, and cultures, who share different views, ideas, experiences and perspectives. Diversity includes: Age, Beliefs, Culture, Ethnicity, Life experiences, Skills and abilities.”9

Employment Equity means appropriate representation of designated groups at all areas and levels of an institution.10 The Employment Equity Act states “designated groups” (DGs) means women, aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities.11 “Members of visible minorities” means persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race, or non-white in colour.12 The CAF does actively not recruit persons with disabilities due to the bona fide occupation requirement of Universality of Service. However, CAF members who become disabled and continue to meet the Universality of Service requirements are welcome to remain in uniform. The CAF EE goals are: 25.1 percent for women, 11.8 percent for visible minorities, and 3.4 percent for Aboriginal peoples.

In 2011, Rear-Admiral Smith, then the Chief of Military Personnel (CMP), stated: “The capacity of any group is greatly enhanced when it enjoys a diversity of contributions in terms of expertise and experience. Furthermore, to remain credible in a democratic society, both DND and CF must enjoy the support and the confidence of the Canadian public. A major factor of that support involves how representative it is of the population. Thus, its composition must reflect the gender and ethno-cultural composition of Canadian society.”13 If the CAF wants to remain credible, it is important to make a concerted effort to increase the number of women, visible minorities, and Aboriginal members in the CAF.

Realistic Goals?

According to the on-line Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a goal is the end toward which effort is directed. This is not to be confused with a target, which is a fixed number or percentage of minority group members or women needed to meet the requirements of affirmative action.14

|

Women |

Aboriginal Peoples |

Visible Minorities |

Person with Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

CF EE Goals |

||||

25.1% |

3.4% |

11.8% |

N/A |

|

CF EE Representation Rates |

||||

By Component |

||||

Regular Force |

14.1% |

2.2% |

4.4% |

1.2% |

Primary Reserve |

16.6% |

2.1% |

6.6% |

1.2% |

Regular Force + Pres |

14.8% |

2.2% |

5.1% |

1.2% |

By DEU |

||||

Navy |

18.3% |

2.2% |

4.9% |

1.2% |

Army |

12.5% |

2.3% |

5.4% |

1.3% |

Air Force |

18.9% |

1.9% |

4.4% |

1.0% |

CF Enrolments |

||||

FY 11/12 | ||||

Regular Force |

13.6% |

3.5% |

6.7% |

1.0% |

Primary Reserve |

13.5% |

4.1% |

7.9% |

0.6% |

FY 10/11 |

||||

Regular Force |

12.7% |

3.3% |

6.2% |

1.0% |

Primary Reserve |

19.3% |

1.0% |

4.7% |

0.5% |

CF EE Goals and Statistics

(as of June 2013)

While the percentages of serving CAF Designated Group (DG) members is substantially lower than the current EE goals, we must not forget that significant progress has been made since the DGs were first measured and reported upon in 2003. In addition, while something must be done to reverse the recent trend of recruiting a smaller percentage of women, let us not forget that the number of women in the CAF is almost ten-fold what it was 50 years ago.

The Directorate of Human Rights and Diversity (DHRD) calculates the CAF EE goals, utilizing a Workforce Analysis (WFA) Methodology that was developed in 2004 and approved by Human Resources and Skills Development Canada and Treasury Board. The Canadian Human Rights Commission, as the CF’s EE auditor, reviews and endorses the EE goals. While writing this article, I was informed that the WFA Methodology is acknowledged to be flawed by both internal and external stakeholders, and that it is under review. A Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (DGMPRA) research project is underway to propose a new improved measure of the Military Factor Effect and a new WFA Methodology that can be used to set future CAF EE goals. That being said, I still believe that the current goals are reasonable and achievable, and, quite frankly, low, considering the actual availability in the work force of women, visible minorities, and Aboriginal peoples. While the number of DG members in occupations similar to those in the CAF has been lower than the overall availability of DG members in the work force, those numbers are increasing, and will continue to increase, given changing Canadian demographics.

For example, when the propensity for women to join the military was studied over 10 years ago; it was measured at 20 percent.15 In 2007, 40 percent of the subset of the Canadian population interested in joining the CAF were women.16 The same report identified that the subset of the Canadian population interested in joining the CAF included 10 percent Aboriginal peoples, 31 percent visible minorities, and only 59 percent white Canadians.17 I believe that other factors are responsible for the lower recruiting numbers of DG members. As an example, in the RCMP, which is arguably another non-traditional militant career, women form 20.4 percent of the regular members.18

A 2011 report indicated that 51 percent of Chinese-Canadian youth considered a career in the military as a last resort. However, 34 percent disagreed with this view.19 The report identified three methods of influencing the Chinese-Canadian population opinion of military careers: meeting Chinese-Canadian veterans who had achieved success after their military career; seeing Chinese-Canadian CAF members, particularly senior ranking individuals, in recruitment efforts; and communicating in Mandarin and/or Cantonese.20

A 2012 report on the propensity for Asian- (not including Chinese) and Arab-Canadian youth identified that the military was seen as a career of last resort (40 percent). However, an equal proportion (41 percent) disagreed with this view.21 The same research identified that this group reported that they were more likely to consider a military career (21 percent) than the general public youth (13 percent).22 The research brought forward three challenges facing the recruitment of this group: parents and the community are unwilling to recommend a military career; the perception that it is easier and more prestigious to achieve professional success through civilian universities; and only one percent identifies the military as a preferred career, likely due to the lack of successful examples from within their community.23

The reality is that the face of Canada is changing, and it is time to take focused positive action towards increasing diversity.

Credit: DND photo IS2006-1140

Female doctor taking blood pressure

One factor that should be remembered when analyzing the current CAF EE and diversity statistics is that statistical information regarding gender and first official language are tracked in the Human Resources Management System. At any given time, a report can be pulled to determine those statistics. However, the disclosure of whether a person is a visible minority, Aboriginal, or a person with disabilities is gathered through the voluntary completion of Parts B of the Self-Identification Census (or the Self-ID census), which was initiated in 2001. I know that some visible minority and Aboriginal people are not self-identifying, due to a desire to be recognized by their own merits. They do not want to receive additional opportunities based solely upon their ethnicity. They do not seem to realize that self-identifying does not affect a person’s career, as the information is kept strictly confidential. The data generated through the Self-ID census is only used for statistical purposes.24 A complete census would help project a more accurate picture of CAF demographics, which may increase the likelihood of DG members enrolling in the military.

It is conceivable that there are more Aboriginal and visible minority members than are currently being accounted for. I only self-identified as Métis near the end of my career, as the form did not ‘get on my radar’ until then. Serving Aboriginal NCMs want to know, “where are the Aboriginal officers?”25 I encourage any serving members who have yet to self-identify to do so.

Those who are interested in playing a more active role in diversity recruiting should look into the newly revamped CFRG “Recruiter for a Day” program. CAF members, who are also in at least one of the Designated Groups, will have the opportunity to register to participate in recruiting initiatives across Canada. Having more women, visible minorities, and Aboriginal CAF members in uniform appearing in public will help combat the widespread misperception that the military is only for Caucasian males.

The CAF has stated that it intends to make efforts to meet the EE goals. As of the autumn of 2011, CFRG reported upon the success of achieving the Strategic Intake Plan, which is tied to finding sufficient qualified candidates for each occupation and for the Aboriginal Special Measure programs. CFRG also reported on the overall number of DG members recruited, but this information was not accorded nearly the same importance as meeting the overall goals by occupation. CFRG, like most organizations, has a history of paying attention to the things that are measured. DHRD sets CAF EE goals by occupation and DG. Given that there is still quite a gap between the EE goals and the percentage of DG members currently serving, if the CAF is serious about increasing the diversity of our military, CFRG should be directed to exceed the current EE plan recruitment goals and should report on progress made by occupation and DG on at least a yearly basis.

The vast majority of visible minority Canadians live in metropolitan areas. In order to increase the number of visible minority recruits, metropolitan recruiting centres should be given proportionally higher visible minority goals than the recruiting detachments in small cities and rural areas. An effort should also be made to have visible minorities and women as staff at the Metropolitan Recruiting Centres. Recruiting Centres in urban areas with high populations of Aboriginal peoples should be staffed in part by Aboriginal CAF members, and should be given a proportionally higher goal for Aboriginal recruitment.

Reaching the Tipping Point

Malcolm Gladwell was named as one of Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in 2005. He is the author of several books on how people communicate, interact and succeed. Gladwell’s first book The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference outlines three characteristics that define how social epidemics take place.26 The “Law of the Few” recognizes that a few people, whom Gladwell categorizes as: connectors, salesmen and mavens, are those who have the greatest influence spreading social change. “Stickiness Factor” refers to making the message memorable. Gladwell also speaks of how context reinforces a message. Lastly, Gladwell’s “Rule of 150” refers to how groups perform much more effectively when they are kept small, that is, under 150 people.

There is some validity in modelling our Diversity Recruiting efforts upon Gladwell’s Tipping Point theory. When those who hold social power decide that the military is a good career path for their community members, they will influence them to apply to join the CAF. However, in order to reach those people the CAF has to present the recruiting messages in a ‘sticky’ way. The best way to do so is in small groups of 150 or less. The following sections describe how the CAF could tip the balance towards increasing diversity.

Credit: DND photo HS2007-L0001-014

Female sailor holding rifle

Influencer Events

Research has consistently shown that the best way to attract minority groups to an organization is to have people they can identify with who are already serving in that organization do the outreach.27 In 2012, CFRG began holding Influencer Events targeted at those holding influence with young women and visible minorities. I had the privilege of being one of the officers who met with Women Influencers in Halifax in March 2012. CFRG gathered over 20 serving women to share their experiences with 50 women who worked in career counselling roles at colleges and universities and job placement agencies. In addition, several young women (peer influencers) attended the three-day event. In Human Resources parlance, the women were given a realistic job preview of what it would be like to serve in the Royal Canadian Navy, and, by extension, the CAF. During this outreach event, I learned that women held several misconceptions about military service. Many believed that if they joined the military they would be subject to harassment and/or assault. They also thought that they would have to conceal their femininity and that they would not be able to have families. In addition, they had concerns about the physical fitness requirements. Meeting with serving CAF women alleviated their concerns. Many of the participants shared that they had dreamed of a military career only to be dissuaded by their families or other key Influencers in their lives. The feedback from this session was overwhelmingly positive. The Women’s Influencer events continue to take place, indicating that CFRG is taking positive action towards reversing the decreasing percentage of women to join the CAF in recent years.

Credit: DND photo IS2013-2001-033 by Master Corporal Marc-André Gaudreault

Female avionics technician servicing a CF-18 Hornet

Tailored Recruiting Messages

I propose that the CAF ‘tweak’ the recruiting message to make it more ‘sticky’ for the targeted DGs by focusing upon both the career opportunities and upon the practicalities of military service. The military is one of the few organizations where everyone is paid equally, based upon their rank and qualifications. Unlike many civilian organizations, gender and ethnicity do not negatively affect a person’s pay and benefits. Further, there exists a superlative benefits package, including full medical and dental, subsidized maternity and parental leave, and a defined benefit pension plan. No prior job experience is required; the CAF trains and educates people for their designated military occupation. This includes fully subsidized post-secondary occupation for a variety of professions. The profession of arms should also be explained particularly to visible minorities as many families in that group influence their children to follow a professional career, but focus upon “…traditional professions such as law, medicine, engineering and business.”28 The message delivered to visible minority and Aboriginal Influencers should also include the transferrable leadership skills that can be brought back to the community upon retiring from the military.

In addition to the traditional marketing methods of print ads, radio, and television commercials, and the FORCES.CA website, targeted social media campaigns, such as the Women Canadian Armed Forces Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/pages/Women-Canadian-Armed-Forces-Femmes-Forces-arm%C3%A9es-canadiennes/415132768542364?ref=ts&fref=ts should be implemented for visible minorities and Aboriginal peoples. The Women CAF Facebook page showcases serving Canadian women, and it shares mainstream media articles about women in the CAF.

Credit: CFRG op_w_15f

Female CF-18 pilot in front of aircraft

Realistic Job Preview - Special Measures Programs

An effective way to directly educate DG members about the military is to provide them with an enhanced realistic job preview, a ‘try before you buy’ program. The CAF currently runs several programs for Aboriginal peoples; that are considered Special Measures programs under the EE Act. These programs allow Aboriginal peoples the opportunity to experience military service for a specified period of time with no obligatory service on completion of the program. All staff who with these programs are required to complete the Aboriginal Awareness Course (AAC).

The Canadian Armed Forces Aboriginal Entry Plan enables Aboriginal peoples to experience three weeks of training similar to the Basic Military Qualification (BMQ) course. This allows the candidates an opportunity to decide if they would like to have a military career. The results are overwhelmingly positive, with 85 percent of the graduates from the last two years applying to join the military while still on course. The Aboriginal Summer Programs Bold Eagle, Raven, and Black Bear are six-week reserve BMQ courses that include all the training taught to mainstream Canadians, as well as an Aboriginal culture component. In the last two years, over half of the graduates have indicated their intent to join the military. There is often a delay of a year or two, as these candidates are strongly encouraged to complete high school before joining the armed forces. Completion of the BMQ helps some of the candidates to graduate high school, as several provinces recognize the military training for high school credits.

The newest of these programs is the Aboriginal Leadership Opportunity Year (ALOY), conducted at the Royal Military College (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario. In this program, up to 20 Aboriginal Youths are given the opportunity to complete up to a full year’s worth of university level credits, while learning military skills, leadership, and participating fully in a sports program, as well as other RMC clubs. In addition, there are Aboriginal Culture awareness activities such as smudging, drumming, and singing. Since its inception in 2008, half the ALOY graduates have applied for further CAF service. In January 2013, Acting Sub-Lieutenant Nicole Shingoose became the first ALOY graduate to be commissioned as an officer upon graduation from RMC.

Credit: DND photo KN2013-301-007 by Steven McQuaid, Base Photo Kingston

Lieutenant-General Peter Devlin (centre), then-Commander Canadian Army, at Aboriginal Leadership Opportunities Year (ALOY) graduation ceremonies, Kingston, Ontario, 2013.

Context - Systemic Changes

There are systemic changes to context that can be undertaken to further encourage DG members to join the CAF. While there has been a concerted effort to portray a diverse face through CFRG, with changes to the FORCES.CA website, recruiting commercials and posters, the CAF has yet to put in place a system to ensure that images used in leadership and other professional publications acknowledge the diverse face of serving military members. While there is no policy currently in place, there are several examples of CAF publications that reflect diversity, for example, Duty with Honour: Profession of Arms in Canada 2009. This policy could be promulgated by the Public Affairs Branch and the Directorate of Human Rights and Diversity. In addition, this policy could be included in the Chief of Defence Staff Guidance to Commanding Officers chapter entitled Human Rights and Diversity. This chapter should also ask Commanding Officers to encourage their personnel to complete the Self-ID Census.

Credit: DND photo KN2013-361-106 by Brad Lowe, Base Photo Kingston

A Sikh RMC cadet on parade

As previously mentioned, there should be a concerted effort to post DG members to recruiting centres. This should be taken one step further by posting more DG members to the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School (CFLRS). The CFLRS staff should receive Awareness Training regarding the multicultural nature of Canada.

Retention—the second half of the story

While recruiting a higher percentage of DG members is fundamental to increasing the Diversity of the CAF, retention is equally important. The 2009/2010 Annual Report on Regular Force Attrition indicated that women’s attrition was no different from men’s in their early career. This changed at nine years of service and beyond, when the levels of attrition for women were generally higher than that of men29. Visible Minority and Aboriginal Attrition is difficult to measure, due to the high percentage of people who chose not to self-identify. “For officers, attrition at 9 and 20 YOS (Years of Service – Ed.) is higher for Aboriginal peoples and visible minorities than members who belong to neither of these designated groups. … For NCMs, attrition at 0 and 20 Years of Service is lower for Aboriginal peoples and visible minorities than for members who belong to neither of these designated groups.”30 Research has identified several retention incentives that would be beneficial to women, visible minorities, and Aboriginal peoples, and, by extension, all other military members. Three of these incentives are highlighted here: Mentoring, Flexible Work Arrangements, and Affordable Childcare.

Mentoring

Mentoring has proven to be extremely effective with women and visible minorities, particularly when the one being mentored can relate to the mentor by reason of sharing gender or ethnicity.31 A Mentoring program that allows people to select a mentor with whom they can identify could encourage DG members to pursue a long term military career. When I retired from the military last year, the DND Mentoring Program was only open to those in the Public Service. This program could be expanded to include all DND and CAF members. Further, the search function could be expanded to include the ability to search beyond job functions, interests, language, and gender, to ethnicity and religion. If this task is deemed too complex for the current program, there are ‘off the shelf’ mentoring programs that can be customized to DND/CAF that would facilitate an all-encompassing mentoring program.

Flexible Work Arrangements

Lieutenant-Colonel Telah Morrison’s Military Defence Studies paper, “Striking the Balance to Become an Employer of Choice: Solutions for a Better Work-Life Balance in the CF,” outlines the business case for Flexible Work Arrangements (FWA). Morrison’s seminal work on striking the right work life balance to make the CF an employer of choice offers concrete suggestions on how FWA currently in place for the Public Service could be used for military members. The following figure was taken from Morrison’s paper.

Policy/Program |

Description |

|---|---|

Part-Time Work |

Permanent position, but fewer hours/days than a regular work week |

Job-Sharing |

Full-time position with duties and responsibilities shared among two or more part-time employees |

Flexible Hours of Work |

Employee works standard number of hours per day, but has some choice in start and finish times |

Compressed, or Variable Work Week |

Extended hours per day in return for periodic days off |

Telework |

Work from home on a regular basis, but not necessarily every day |

Public Service Flexible Work Arrangements (FWA).32

Several of these flexible work arrangements are currently being used informally throughout the CAF. These policies could be formalized and implemented within the current construct of part time (Reserve Force) and full-time (Regular Force) service. Such policies would no doubt be welcomed by many military members, and they would increase the retention of highly skilled personnel. Morrison provided examples of one male and one female officer who could have been actively employed, using ‘telework’ rather than being forced to be on extended leave without pay while their military spouses were posted outside of Canada.

In July 2013, Catalyst released Flex Works, a report based upon 50 years of research, which listed core concepts related to workplace flexibility. The four core concepts most relevant to this article are as follows. Implementing flexibility programs can be expensive, but the benefits usually outweigh the costs. Industries and professions with roles that cannot be performed virtually can still include flexibility options for workers. Flexibility policies can demonstrate an organization’s commitment to diversity and inclusion by including modern definitions of family. And formal flexibility policies should be communicated and celebrated by leadership to demonstrate support.33

Affordable Childcare

Morrison also makes the business case for the CAF establishing Affordable Childcare. She recommends building a program similar to that established by the U.S. Department of Defence by expanding in the services already in place at many of the Military Family Resource Centres. This program would increase the deployability of CAF members, reduce the number of lost days, and contribute to higher retention of qualified personnel. As 62 percent of CAF members have children, this retention initiative would ‘work across the board.’ While this would benefit all military families, it is likely to increase retention of women at their mid-career point, as traditionally, women have borne the majority of childcare responsibilities. In the past, there has been a trend of women leaving the military as they started their families.

Credit: CFRG op_w_20f

Female soldiers with Afghan child

Mentoring, FWA and affordable, reliable, and flexible childcare would be excellent retention initiatives that could answer in part the Military Personnel Retention Strategy, Annex A – CMP CF Retention Strategy Campaign Plan, Item Number 26, “Examine career/family balance options for women at mid-career.” While the immediate impact may be more readily measureable for women, these initiatives are likely to help retain both men and women. They may also help recruit and retain visible minorities34 and Aboriginal peoples,35 whom research indicated are less likely to join the military, due in part to the high likelihood of being posted away from their communities.

Credit: CFRG op_m_15f

A CF-18 pilot in cockpit

Conclusion

The Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces have time and again proven that they are up to the challenge of adjusting their cultures to better reflect Canadian mores. The Canadian military can and must significantly increase the percentage of women, visible minorities, and Aboriginal peoples who serve their country in uniform. Canadian demographics are shifting, and these groups will represent two thirds of Canada’s population by 2031. For those who think my math is sketchy, here is how I arrived at that figure. Statistics Canada speculates that by 2031, visible minorities will constitute 30 percent of the population, and Aboriginal peoples will constitute at least four percent of our population. It is safe to assume that half the members of these groups will be women. My math consists of 34 percent (visible minorities and Aboriginal peoples), times 0.5 (removing women to avoid duplicate accounting), plus 50 percent (women in Canada), for a total of 67 percent. If changes are not made now, our military will cease to reflect the Canadian population.

I believe that the CAF can initiate the recommended recruiting and retention initiatives listed in this article, and significantly increase the Diversity of the CAF. I used to do business planning for the CAF Aboriginal Programs, and I know how much it costs to recruit CAF members. I am confident that the funds saved by lowered attrition will offset the costs of implementing these programs.

Tailoring the recruiting message to DGs, and delivering this message through Influencers Events, Social Media efforts, such as Facebook and Twitter, and through the continuation and possible expansion of Special Measures programs, for example, implementing three-week realistic job preview programs for women and visible minorities, would all help the CAF reach the ‘tipping point’ in recruiting a more diverse military.

This would be re-enforced by making systemic changes to the context in which the public sees the military, such as ensuring that all recruiting centres, advertising, and publications celebrate the diverse face of the military.

A formal Mentoring program, FWA, and affordable childcare would have a positive impact upon the retention of quality individuals, regardless of their gender or ethnicity. Research indicates that these programs would encourage greater retention of women, and could increase the recruitment and retention of all visible minorities and Aboriginal peoples.

In addition, the success of these efforts will be substantially increased if CFRG regularly reports upon the progress of recruitment efforts aimed at DGs. Change efforts are substantially more effective when they are observed, analyzed, and reported upon.

I will conclude by quoting Gladwell.

In the end, Tipping Points are a reaffirmation of the potential for change and the power of intelligent action. Look at the world around you. It may seem like an immovable, implacable place. It is not. With the slightest push—in just the right place—it can be tipped.

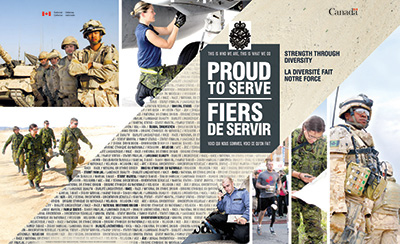

Credit: DND

‘Proud to Serve’ publication banner

Notes

- Recruiting and Retention in the Canadian Forces (data up to 31 March 2011) Backgrounder, at http://www.forces.gc.ca/site/news-nouvelles/news-nouvelles-eng.asp?id=3792.

- Demographic means relating to the dynamic balance of a population especially with regard to density and capacity for expansion or decline. Online Merriam-Webster dictionary at http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/demographics.

- Marie Drolet, “Why has the gender wage gap narrowed?” Statistics Canada - Spring 2011, Perspectives on Labour and Income, 2011, at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2011001/pdf/11394-eng.pdfp, p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Éric Caron Malenfant, André Lebel, and Laurent Martel, Statistics Canada Highlights “The ethnocultural diversity of the Canadian population.” 2010 at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-551-x/2010001/hl-fs-eng.htm.

- Statistics Canada “Population by mother tongue, Canada, 2001, 2006 and 2011,” 2011, at http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/ref/guides/98-314-x/tbl/tbla01-eng.cfm

- Statistics Canada The Daily “Population projections by Aboriginal identity in Canada 2006-2031,” 7 December 2011, at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/111207/dq111207a-eng.htm.

- Roland Hébert, Mike Crew, Sylvain Delisle, Sarah-Jane Ferguson, Kathryn McMullen, Statistics Canada: Educational Portrait of Canada, 2006 Census: ”Aboriginal population, 2006 Census.” 2008, at http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/as-sa/97-560/p16-eng.cfm

- National Defence and Canadian Forces “What is Diversity web page,” at http://www.civ.forces.gc.ca/benefits-avantages/div-eng.asp accessed 13 May 2013

- MILPERSCOM (MPC)/Chief of Military Personnel (CMP) Employment Equity (EE)Plan – August 2011 To August 2014, Annex B, 16 August 2011, p.B-1/3.

- The Employment Equity Act http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-5.401/page-1.html#h-2 Accessed 13 May 2013.

- The Employment Equity Act.

- MILPERSCOM (MPC)/Chief Military Personnel (CMP) Employment Equity (EE) Plan – August 2011 to August 2014, dated 16 August 2011, p. 2.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary online dictionary, at http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/goals?show=0&t=1370012941.

- Major Eleanor Elizabeth Haevens, “Women in Peace and Security – What Difference Does Canada Make?” Canadian Forces College Military Defence Studies paper, 2012, p. 72, at http://www.cfc.forces.gc.ca/papers/csc/csc38/mds/Haevens.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2013.

- Irina Goldenberg, Brenda Sharpe, and Keith Neuman. “The Interest and Propensity of Designated Groups to Join the Canadian Forces.” Technical Report, DRDC CORA TR 2007-04, 2007, .p. v.

- Ibid., p. v.

- Grazia Scoppio, Presentation to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Leader Development Program on “Leadership and Diversity,” 26 April 2013, Slide 6.

- Ipsos Reid Corporation, Visible Minorities Recruitment and the Canadian Forces: The Chinese-Canadian Population Final Report, 2011. p. 47.

- Ibid., p. 54

- Ipsos Reid Corporation, Visible Minorities Recruitment and the Canadian Forces: The Asian and Arab Canadian Population Final Report, 2012. p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- Ibid. pp. 12-13.

- Phyllis P. Browne, “Visible Minorities and Canadian Forces Recruitment: Goals and Challenges,” DGMPRA TM 2011-021; Defence R&D Canada; September 2011, p. 12

- Felix Fonseca, “Attracting and Recruiting Aboriginal Peoples”, DGMPRA TM 2012-004 March 2012, p. 14.

- Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. (New York, Little Brown and Company, 2000), p. 9

- Browne, p 19, and Fonseca, p. 17.

- Browne, p. 34.

- Attrition and Retention Team Director Research – Personnel Generation Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Department of National Defence, 2009/2010 Annual Regular Force Report on Attrition, p. 44.

- 2009/2010 Annual Regular Force Report on Attrition, p. 35.

- Beth N. Carvin, “The Great Mentor Match: Xerox’s Women’s Alliance cracks the code on successful mentor programs,” (American Society for Training & Development, T+D Magazine), January 2009, p. 50, at http://www.mentorscout.com/about/Mentor-Scout-Xerox-case-study-Jan2009.pdf.

- Lieutenant-Colonel Telah Morrison, “Striking the Balance to Become an Employer of Choice: Solutions for a Better Work-Life Balance in the CF,” Canadian Forces College Military Defence Studies paper, 2011, p. 38, at http://www.cfc.forces.gc.ca/papers/csc/csc37/mds/Morrison.pdf#pagemode=thumbs.

- Catalyst. Flex Works. 2013 at http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/great-debate-flexibility-vs-face-time-busting-myths-behind-flexible-work-arrangements.

- Browne, p. 24.

- Fonseca, p. 17.