Canadian Military Journal Vol 14. No 1.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

CANADA IN THE WORLD

DND photo HS 20017025-005

Amphibious Readiness Group (ARG) cruises in close arrowhead formation.

Task Force 151

by Eric Lerhe

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Commodore (ret’d) Eric J. Lerhe, OMM, MSC, CD, PhD, served in the Royal Canadian Navy for 36 years. After two ship commands, he served as Director Maritime Force Development and Director NATO Policy at National Defence Headquarters. Promoted to commodore and appointed Commander Canadian Fleet Pacific in 2001, in that role, he was a Coalition Task Group Commander for the Southern Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz sector during the ‘war on terror’ in 2002. His PhD was awarded in 2012, and he continues his research into security issues at the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, Dalhousie University.

Introduction

The Canadian naval contribution to the War on Terror attracted little attention at the time, and what did make it through was usually negative. Admitting that reporting events at sea is fraught, this lack of attention is still surprising. Canadian officers were in sole charge of an operating area that stretched 500 miles from Oman all the way to the central Persian Gulf. From October 2001 to July 2003, they commanded over 70 warships, of which 50 came from allied nations. Those ships conducted over 1000 boardings and hundreds of safe escorts of military shipping through the Straits of Hormuz, despite a rising number of maritime terrorist attacks elsewhere. These forces were also able to capture four mid-level al Qaeda operatives, and, more importantly, were credited with preventing hundreds of others from escaping Afghanistan to the Gulf States and Africa. In fact, the US credited the efforts of the Canadian-led coalition naval force in the Gulf of Oman and Straits of Hormuz with preventing the seaward escape of the alleged 20th 9/11 attacker Ramzi bin al-Shibh long enough for the CIA to capture him in Karachi in September 2002. Rear-Admiral Kelly, the overall US naval commander, told the Canadians that “…you people were instrumental in facilitating the arrest by being out here doing the patrols and doing your hails and boardings.”1

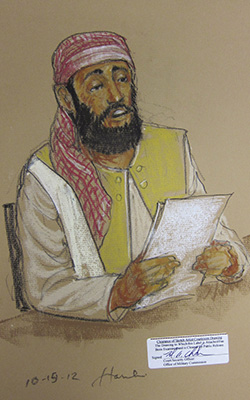

Reuters RTR396HR by Stringer

Artist’s sketch of alleged al Qaeda co-conspirator Ramzi Bin al Shibh on trial, 15 October 2012.

Despite all this, what dominated media reporting at the time was the repeated suggestion that Task Force 151 was covertly assisting the US war in Iraq, despite the Chrétien government’s public stand against any participation in it.2At the same time, the US viewed TF 151’s unwillingness to assist them as sufficiently upsetting; “the last straw for the White House” it was claimed, that it resulted in the cancellation of the US President’s planned visit to Canada in May 2003.3

These contradictory views are probably sufficient reason to probe this operation. Other reasons to dig deeper would include the need to investigate the related charge by Stein and Lang in The Unexpected War: Canada in Kandahar, that the Canadian military leadership “created a trap for the government by urging Canada lead the TF 151.”4 This stratagem involved the military seeking government approval in early February 2003 for Canada to lead this formation in the hope, it was alleged, that it would encourage the government to then approve joining the larger American plan to invade Iraq:

And initially, before Chrétien had made his decision on Iraq, Canada’s generals and admirals probably thought that taking on TF 151 would “help” the politicians make the “right” decision. Surely Canada could not continue to lead this task force and not be part of the Iraq coalition.5

DND photo HS095-114-11

Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and President Bill Clinton.

Stein and Lang also hint that once Canada had both assumed command of Task Force 151 and decided it would not participate in Operation Iraqi Freedom, the military likely strayed into supporting the latter:

Whether or not Canada’s ships in TF 151 actually carried out any duties directly related to the war in Iraq will probably never be known. Yet according to the official record, the Canadian navy somehow managed the seemingly impossible. It ran and participated in a double-hatted naval task force but it did not get involved in command or operational responsibilities related to one of these hats.6

According to Stein and Lang, the overall result was that “…command of TF 151 … undermined the coherence and integrity of Canada’s policy on the war in Iraq.”7 They had some support for their claims with Dalhousie University’s Frank Harvey arguing the Canadian ships “…did not and could not separate the roles between terrorism and the war on Iraq.”8

As a result, the first step for this article will be to present the competing narratives, and then assess the extent to which the case is made for the Canadian military laying a ‘trap.’ Then, it will examine the actual conduct of the Task Force 151 mission to determine whether the government’s directions and policies were flouted by its navy. If nothing else, a detailed review of events might supply some lessons with respect to strategic command in complex operations.

TF 151 as ‘Trap’

The account of this issue by Stein and Lang is brief, and almost all of it is heavily disputed by the key participants. The sole area of agreement is that both the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) and Deputy Chief of Defence Staff (DCDS) recommended in early February 2003 that Canada lead TF 151, a new command established by the US naval commander in the Persian Gulf.9 Up until this time, Canada had only directed Task Group (TG) 150.4, as the sector commander of the Southern Persian Gulf – Strait of Hormuz – Gulf of Oman sector. The Canadian commander, in turn, reported to Commander Task Force (CTF) 150, the at-sea commander of the USN carrier battle group that routinely operates in the Persian Gulf area.

© 1988-2000 Microsoft and/or its suppliers

Figure 1 – Chart of CTG 150.4 Areas of Responsibility.

Richard Gimblett, in his history of Canadian naval involvement in Operation Enduring Freedom, explains that the US military leadership fully recognized that there was a need to maintain Operation Enduring Freedom’s (OEF) maritime anti-terrorist and escort tasks in the southern Persian Gulf as American forces were diverted northwards towards Operation Iraqi Freedom.10 Therefore, Task Force 151 was created to continue the task of interdicting al Qaeda and escorting shipping through the Straits of Hormuz, as al Qaeda had attempted one attack within the Straits in 2002, and had successfully attacked two ships near Yemen. The US area commander also fully realized that a significant number of those OEF coalition forces wished to continue their efforts against al Qaeda and support the US in its broader counter-terrorist effort without joining the war against Iraq.11 Task Force 151 thus had the potential to hold the broader international counterterrorism coalition together, keep the pressure on al Qaeda, and ensure the safety of both military and commercial shipping. The US offered the leadership of Task Force 151 to Canada, because we had the longest running coalition naval command experience in the area as commander of the Straits of Hormuz sector. An earlier, highly favourable US report had noted we were the “logical choice” for area command in this region, due to our specialized training and skills.12

Taking on the task had direct benefits for Canada. Ken Calder, DND’s Assistant Deputy Minister Policy, argued that this mission provided the government with the flexibility to declare them for either Operation Enduring Freedom, or Operation Iraqi Freedom, as the Chrétien government struggled over whether to aid the United States in a potential war on Iraq.

Our challenge was we did not know which way we would go. We had to be in a position where we could go either way, which when you’re dealing with deployed forces, can be a little tricky. We manoeuvred ourselves into a position where basically with respect to the naval contribution, we could declare them as part of Iraqi Freedom, or we could say they were still part of Enduring Freedom. Therefore, we could switch either way without having to move Canadian resources.13

This is partially acknowledged by Stein and Lang, who refer to TF 151 as a “double-hatted” command, although it is likely not what Dr. Calder was describing.14 Rather than decisively declaring those forces for one operation, Stein and Lang state that the Minister understood that the Task Force would be providing support to Operation Enduring Freedom, while also providing “some as yet undefined support to Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) once hostilities had commenced against Iraq.”15 They also point out that senior members of the department of Foreign Affairs, including Minister Graham, also joined by Deputy Prime Minister Manley, had argued for assuming the leadership of the Task Force. The government then agreed to the task, and, according to Stein and Lang, “would worry later” as to how Canada would manage to continue leading the task force after combat operations had begun in Iraq.16

The first ‘worry’ arrived before that. Stein and Lang claim that at the end of February 2003, less than twenty-eight days after they had argued for it, the Chief of Defence Staff and Deputy Chief of Defence Staff reversed themselves and claimed Canada must withdraw from the leadership of TF 151.17 They did this, it is asserted, when they both then realized the Chrétien government was not going to support the war on Iraq:

When they did, Henault and Maddison shifted gears. They told McCallum that Canada would have to pull out of the leadership of TF 151, which it had just assumed, if Ottawa was not going to participate in military operations against Iraq.18

This, then, is the ‘trap’ that Stein and Lang state the military laid for the government.19

DND photo ETD02-0051-17

The Canadian Chief of the Defence Staff, General Ray Henault, addresses the crew of HMCS Ottawa as the ship prepares to depart for Operation Apollo.

There are several problems with both this narrative and its conclusion. General Henault has stated in interview that the interpretation by Stein and Lang of this issue is fundamentally incorrect.20Here he is supported by two other officers who were directly engaged in this issue, Vice-Admiral Maddison, and Rear-Admiral McNeil.21 General Henault also claims that at no time in the Spring of 2003 did he recommend withdrawing Canada from TF 151 or its leadership.22 Yet, Stein and Lang also cite the Chief of Defence Staff as declaring: “The Navy needed a break in the operational tempo,” as the reason for having to withdraw.23 The CDS, after examining his personal notes of this period, has no recollection of making that recommendation, or of providing that justification.24

The statement attributed to the CDS may have its origins in some other context as the Stein and Lang text itself seems to suggest, with its stating that the Canadian Navy had only been involved in TF 151 “for a matter of days” when the CDS allegedly raised this operational tempo problem. Further, at that moment, the Navy was in the process of dispatching an additional frigate and a destroyer to join the two other Canadian warships in the Gulf, thus seriously aggravating its supposed operational tempo problem. In fact, Rear-Admiral McNeil makes clear that the Navy was fighting hard against the Minister’s opposition to sending the additional destroyer.25 With PCO support, the destroyer was sent, but again, it demonstrates that the Navy was not seriously concerned over the operational tempo in March 2003.

Rather than calling for terminating the leadership of TF 151, General Henault has stated that he sought to alert government that there was a significant legal debate now underway within the bureaucracy that would certainly require the Minister’s attention as well as, potentially, that of Prime Minister Chrétien.26 At the very minimum, the strategic direction the Prime Minister had issued in November 2001 had not envisaged that Canadian ships would be required to provide safe escort through the Straits of Hormuz while a major conflict was underway in Iraq. As a result, a change to the government-approved objectives in the theater was required. A confidential interview has confirmed that the required briefing note for the Minister with a letter to the Prime Minister dealing with TF 151, its objectives, and the new strategic environment, was prepared in mid-March 2003.27 These documents would ultimately become the new Canadian Forces strategic direction for the theatre.

Stein and Lang confirm the fact that the legal basis for the mission was now in question. They cite the fact that the Canadian Forces’ Judge Advocate General was of the opinion that in escorting American shipping bound for Iraq, Canada was in danger of being considered a belligerent in the conflict. They also report that he was “… not very popular” with the CDS as a result.28 General Henault has subsequently confirmed that he was less than satisfied with JAG’s interpretation, as he wished to continue having Canada command TF 151.29 He also noted that the contributing navies continued to support TF 151 and Canada’s command of the same. Moreover, those nations had no overriding legal issues complicating their participation. Further, Rear-Admiral McNeil has also stated that the governments of at least two of those nations specifically requested that Canada continue to lead TF 151.30

Subsequently, and entirely in accordance with the Chief of Defence Staff’s wishes, the issue was indeed brought to the Prime Minister’s attention, whereby he made the final decision to continue Canada’s command of Task Force 151. Anecdotally, the Prime Minister is reported to have acknowledged the legal complexity of the issues, stating that they could bring in 20 lawyers to resolve the issue, whereupon they would argue for several years. Alternatively, he was prepared to make a decision right now, and did so in favor of continuing Canadian command of Task Force 151. On 18 March 2003, the day after he announced that Canada would not participate in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Prime Minister Chrétien then signed the revised strategic direction authorizing the changed objectives, the escort mission, and Canada’s continued leadership of TF 151.31 Commodore Girouard, the designated Task Force Commander, acknowledges receiving that just-signed strategic direction authorizing the escort task, as well as other elements of the original Operation Enduring Freedom mission.32 Intercepting fleeing Iraqis was, however, forbidden.

DND photo IS2003-2307a by Master Corporal Frank Hudec

Commodore Roger Girouard (left) and Commander Gord Peskett (right) walk away from a Sea Hawk helicopter on the deck of HMCS Iroquois in the Gulf of Oman, 11 April 2003.

Later, the Prime Minister argued that he endorsed this mission, “…because it was important to the Navy.”33 Indeed it was, but this does seem to be a curious rationale. The Stein and Lang narrative suggests the real reason as they outline how the Department of Foreign Affairs urged the government to retain command of TF 151, “…as a way to mitigate Washington’s inevitable displeasure” over our failure to join the Iraq War.34 It soon became clear via Wikileaks that the Department of Foreign Affairs continued to hold that position. On 17 March 2003, the day Canada announced it would not join OIF, the US Embassy in Ottawa reported that DFAIT’s Assistant Deputy Minister, Jim Wright, had informed them that:

…despite public statements that the Canadian assets in the Straits of Hormuz will remain in the region exclusively to support Enduring Freedom, they will also be available to provide escort services in the Straits and will otherwise be discreetly useful to the military effort.35

He also advised that the Canadian patrol and transport aircraft in the region “are also prepared to ‘be useful.’” This analysis has not been able to determine the extent to which Wright’s message to the US was authorized by Ministers. However, Foreign Minister Graham is on record as endorsing the Canadian leadership of the task force, stressing the ill-effect it would have upon Canada-US relations if we pulled out, arguing TF 151 was simply a continuation of our original mission, and noting that allies like the French had no legal problems with it.36 The mission also fell well within the curious ‘double-hatted’ construct accepted by the Minister of National Defence. Finally, the just-discussed strategic direction change sought from the Prime Minister, and then issued to Commodore Girouard, fully authorized the escort mission to continue, despite Canada’s decision to not support OIF.

DND Photo IS2003-2327a by Master Corporal Frank Hudec

On HMCS Regina, bridge lookout silhouetted against warship’s searchlight, 15 April 2003.

Task Force 151 Doing the ‘Impossible’

The next section will attempt to assess how carefully Task Force 151 leadership remained within the government’s publicly stated intention that its role be restricted to supporting Operation Enduring Freedom.37 Certainly, Frank Harvey of Dalhousie and Kelly Toughill of The Toronto Star had grave doubts this could be achieved, and they were ultimately convinced that the Task Force ended up assisting the Operation Iraqi Freedom mission.38 Stein and Lang carefully avoid declaratory statements on this subject, hinting instead that the extent to which TF 151 assisted OIF “…will probably never be known,” while suggesting that the Canadian Navy must have “…somehow managed the seemingly impossible” by claiming not to have done so.39 They also claim US complicity in this effort, arguing the blurring of the OIF and OEF roles was “…probably deliberately encouraged” by the US, who, in their view, “considered these operations as a single integrated mission.”

The mission thus begins with Stein and Lang asserting that the Task Force’s tasks were now limited “…to those that were legitimately part of OEF.” Significantly, their description of this phase skirts the fact that shipping escort was always part of OEF, and it would continue to be so under the terms of the just-signed revised strategic direction. Similarly, the Defence Minister continued to state publicly that Task Force 151 worked “… exclusively on Operation Enduring Freedom” without ever mentioning the escort function even when he was specifically asked by the media what tasks might be involved.40 Stein and Lang also concluded somewhat surprisingly that “…the policy with respect to TF 151 was now clear,” and that it was “the Navy’s responsibility to make the policy work.”41

A series of media interviews by naval officials certainly made clear that they thought the escort function was central to the TF 151 task. A DND spokesperson at Central Command Headquarters repeated the Government’s policy on 11 February 2003, stating the Task Force would indeed be “…sticking exclusively to Enduring Freedom.”42 However, the resulting Globe and Mail article confirmed this would include escort operations, protection of shipping, and interception of suspect vessels. On 14 February 2003, Commodore Girouard, its commander, made clear to the media that he would be coordinating the escorts of “undefended ships and tankers,” and particularly so in the Straits of Hormuz. However, the key to assessing whether he remained within the government’s orders requires a detailed breaking down of his sub-tasks.

Under Operation Enduring Freedom, these involved interdicting fleeing al Qaeda and Taliban leadership figures, escorting military shipping, and providing close escort to the US carriers in the region whenever such was required. The Canadian naval task groups were also authorized to track down and arrest Iraqi oil smugglers running the UN embargo, but that illicit activity had largely ended by 2003.43 The warships’ presence in the area also contributed to ensuring the safety of other shipping in this heavily-traveled area, but this task was not formally stated.

DND photo IS2003-2240a by Master Corporal Frank Hudec

HMCS Regina ‘lights up’ a suspect vessel prior to a night boarding in the Gulf of Oman, 5 April 2003.

Of these assigned sub-tasks, only the escort of shipping was initially contentious, and this became so well before the formation of TF 151. Under Commodore Murphy’s command of the Canadian Task Group in late 2002, the build-up of American forces in Kuwait and elsewhere preparing for Operation Iraqi Freedom was beginning to involve the use of commercial shipping to carry the needed military material. Under the earlier Operation Enduring Freedom rules, these would not receive a close escort through the Straits of Hormuz, as only naval shipping was considered to merit that dedicated protection. All this unfolded without incident, until the US commander requested close escort be assigned to a particular commercial vessel, triggering the Canadian commander to request its type of cargo.44When this was not forthcoming, he declined to assign an escort from within his multinational formation, and the US commander then had to assign a USN warship to the task. The unstated Canadian logic here was that the OEF status quo applied wherein commercial vessels, even if there was a high likelihood they contained valuable military cargo, did not get close escort, but benefited from the area support of the coalition warships, as did all other shipping in the area, be it related to the coalition or not. Also unstated by the USN, the Canadians and the other naval coalition members had a general sense that providing close escort to commercial vessels with likely OIF-bound cargo was ‘a bridge too far’ for the coalition’s non-US membership. Almost all the governments contributing ships to the coalition had declined OIF participation, and none likely had issued rules of engagement authorizing direct support to it. As has been shown, Canada’s political leaders in particular avoided any public mention of the escort task, preferring to fall back upon the claim that Canada was simply continuing its OEF functions.

The second sub-task flowing from the original OEF mandate was the interdiction effort against the al Qaeda and Taliban leadership. Problems only arose here with media supposition that the task force would stray into the task of rounding up fleeing Iraqi officials. Kelly Toughill, reporting for The Toronto Star, extended this quite a bit further and argued, correctly, that Canadian ships passed the crew lists of all the suspicious vessels they encountered to the US master terrorist database.45 As senior Iraqis were also on the list, Toughill then concluded that “…Canadian sailors are actively hunting Iraqis at sea on behalf of the United States,” and that, “If any are found, they are turned over to US authorities.” This was completely incorrect, although Toughill attempts to reinforce this claim by pointing out that two such “suspects” were captured by the Canadian Navy using such a list, and that they were turned over to the US in July 2002.

DND photo HS2002-10218-06 by Master Corporal Michel Durand

HMCS St. John’s small boat inspection team and boarding party verify the passports and papers of two ‘go fast’ aluminum boats suspected of carrying terrorists, 4 August 2002.

As the author was commanding the task group that made those first two al Qaeda captures, I have some familiarity with the process, and it was not as automatic as Toughill provides. Richard Williams explains the process well in his analysis of naval operations in the Persian Gulf, wherein he points out, first, that “…the USN was willing to let Canadian legal opinions dictate the terms of reference” for the seaborne interdiction operations.46 Second, Canada insisted the US provide not only the basis for claiming the suspect’s al Qaeda affiliation, but also his specific terrorist activity or role. Finally, if that data was not convincing, we would not detain, and on at least two occasions, we refused a US request to detain someone who was on their list. Commodore Girouard continued to apply this principle and in addition received specific instructions from Ottawa within his new guidance to not turn over any fleeing Iraqis to US forces.47When he confirmed this in a media interview, Ambassador Cellucci claims he was “stunned” and “flabbergasted” by this approach, and later called the Canadian position “incomprehensible.”48 Citing an unidentified source, Robert Fife of The National Post argues that Canada’s decision on not intercepting Iraqis was “…the final straw for the White House” in its decision to cancel the President Bush May visit to Ottawa.49

Commodore Girouard then quickly confirmed the extent to which he intended to follow the government’s often-less-than-clear direction. Soon after combat operations had begun in Iraq, he received reports of potential Iraqi commercial vessels flying false flags heading south toward the Strait of Hormuz with mines.50 When one was discovered near the Straits, he alerted NDHQ, and then ordered the HMCS Montreal to do a consensual boarding, which the master granted. During that boarding, they discovered five Iraqis sufficiently fit and equipped to be considered potential Special Forces members, but no mines or associated equipment. He alerted the US naval commander’s staff as to his increasing suspicions, but, to his surprise, the US command staff ordered that the vessel be released. The Montreal then withdrew her boarding party, only to have the US staff change their mind thirty minutes later, and request the Canadians remain aboard. At that point, Commodore Girouard interceded, and informed them that Montreal’s team had departed, and could now not return to the vessel. He explained that he had previously enjoyed the right to investigate the vessel, based upon the possible threat it posed shipping in the Straits of Hormuz. Now, however, it was clear that the vessel posed no such threat, and the only possible reason for returning to it was to interdict Iraqis – a task he was not authorized to do. The US commander reportedly fully understood Canada’s position, and assigned a USN vessel to conduct the boarding.

© 1988-2000 Microsoft and/or its suppliers

Figure 2 – Chart of CTF 150 and CTF 151 Areas of Responsibility.

That incident and many others also argue strongly against the Stein and Lang suggestion that the United States viewed this as “a single integrated mission,” and attempted to blur any distinction between OIF and OEF. As has been demonstrated, the US split the naval vessels in the Persian Gulf area into two distinct task forces under separate commanders: TF 150 supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom in the North, with TF 151 conducting OEF in the southern Gulf. As Figure 2 shows, they were also geographically separated by the 28 degree, 30 minute north latitude line. Finally, they put the two task forces on separate communications plans with separate intelligence support, with only a single High Command voice link joining CTF 150 and CTF 151.

This separation did not seriously hamper Commodore Girouard’s ability to maintain effective control of the Canadian, French, New Zealand, Italian, Greek, and, frequently, US ships in its task force. His monitoring of the only link to the other force, the Area High Command Net, did, however, provide occasional snippets of data on the Iraq campaign, while at other times, it was clear that data potentially critical to his forces was being denied. When the commodore reported elements of the first to NDHQ, he found that he was immediately accused of becoming enmeshed in forbidden OIF planning, and was told to desist.51 On the other hand, when the High Command Net revealed that a potential chemical weapons attack was underway, his attempts to determine its location were met by a most disturbing silence as the American-British-Australian discussion of the event was quickly moved to OIF-only nets.52

This was one more example of the extent to which the US, rather than attempting to blur the distinction between OEF and OIF, was actively separating the two. Commodore Girouard then further reinforced that division in publicly and privately rejecting suggestions that his ships intercept Iraqis. In fact, whenever the US requested a task that was on the limits of the OEF mandate, the data was passed back to Canada for review by the DCDS, where it was then rejected when appropriate by the CDS, who then briefed the Defence Minister accordingly.53 In judging the extent to which this effort was successful, it is interesting to note that Girouard was heavily critiqued by Stein and Lang and the Canadian media for doing too much for the Americans, just as the American Ambassador complained he was doing too little. In fact, the only votes of support the Canadian Navy received for its efforts in Task Force 151 were from the Allied navies that very much wanted Canada to lead them in OEF. France was particularly enthusiastic about the way the Canadian Navy was able to maneuver between multiple competing political demands. On completion of Task Force 151, the head of the French Navy sent a letter to Canada praising its theatre commanders for their successful management of operations and rules of engagement “…dans un environment mouvant et complexe.”54

DND photo IS2003-2328a by Master Corporal Frank Hudec

HMCS Regina’s searchlight illuminates yet another suspect vessel in the Gulf of Oman, April 2003.

Conclusion

Regrettably, this analysis was not able to provide a conclusive finding as to whether the ‘trap’ allegation was justified. This is because the participants are split into two camps who disagree over how the events unfolded, and there is a lack of released government material to back up either claim. Circumstantial evidence supports the Chief of Defence Staff’s position that no trap was involved, and that he never recommended withdrawal from the mission. Rather, the more logical conclusion is that he sought to apprise the Prime Minister of the developing legal issues brought on by Operation Iraqi Freedom running currently with Operation Enduring Freedom, as it was his duty to do. Stein and Lang themselves confirm the seriousness of the developing legal problem. That the Prime Minister was briefed and new guidance issued further buttresses his case. So does the ongoing effort to prepare further ships for Task Force 151 and to attract allies to it. It is hard to see one doing this if the underlying plan was to scupper the mission.

The sheer complexity of mounting this kind of conspiracy in Canada and with allies also argues against the ‘trap’ allegations. Any plan for an international military operation involves an extended series of negotiations within DND, with other federal departments, and, finally, with allies. This makes mounting a conspiracy difficult. Even within a single department such as DND, there would be difficulties. Ken Calder, the Assistant Deputy Minister Policy, and a major participant in these negotiations over many decades, puts this well:

The whole business of Task Force 151 and the kind of convoluted account of that in the Stein and Lang book about how, you know, this was done in order to ensnare… Quite frankly, things like that are too complex for most people in National Defence to manage.55

One also has a particularly difficult time accepting that France, a vigorous opponent of the US effort in Iraq, would have joined TF 151 and encouraged Canada to lead it if there was any hint that this was a ‘backdoor’ way of getting Canada, or any other nation, seduced into the US-led, anti-Iraq coalition.

DND photo IS2003-2253a by Master Corporal Frank Hudec

Members of HMCS Regina’s naval boarding party enroute in a Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB) to a suspect vessel in the Gulf of Oman, April 2003.

This analysis was able to be more definitive with regard to the attending claim that once the task force mission had been approved, the military disregarded political direction and “…undermined the coherence and integrity of Canada’s policy on the war in Iraq” by assisting the United States.56 Rather, the evidence is overpowering that the Canadians within Task Force 151 were entirely successful in following the government policy of remaining “exclusively within Operation Enduring Freedom.” This is not to say that their efforts, and particularly their efforts in escorting military shipping, did not support Operation Iraqi Freedom. They certainly did. However, it is clear that the Chrétien government fully understood the escort task was implicit in the OEF mission, while also avoiding any public mention of that task or its increasingly obvious connection to OIF. In this particular regard, the Stein and Lang claim that “…command of TF 151 … undermined the coherence and integrity of Canada’s policy on the war in Iraq” can only be viewed as astounding as there was no cohesion within the policy, nor was there intended to be.57 The DFAIT view that Canada’s performing this mission would offset the damage to US relations caused by our refusal to join OIF was the source of that incoherence. The Chrétien government then endorsed that aim, and via a process Harvey has aptly described as “dishonest denials,” attempted to suggest otherwise to the Canadian public.58 Only in the last paragraph of their chapter on TF 151 do Stein and Lang finally confirm that the policy also lacked integrity:

The story of Canada’s policy on the war in Iraq is also a story of political leadership that spoke with one “principled” voice to Canadians and another, quite different, “pragmatic” voice in Washington. Fortunately, few in the public could hear the two voices at the same time.59

In spite of this, this narrative does underline that at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels, Canada was the Task Force commander of choice. The Canadian readiness to lead those allies who would not join Operation Iraqi Freedom was quickly accepted. Moreover, the other participating governments urged us to continue leading it. One must, however, be cautious here. That is, those governments that joined us probably did so largely to signal support to the broader war on terror, to show they did not desire a complete break with the US, and that they may have, like Canada, considered contributing to Task Force 151 as a side payment for not joining the OIF. On the other hand, no other nation enjoyed Canada’s high interoperability with the US, none ever challenged us for that leadership over the five years we were in the area, and the US never suggested a command change while also sending its ships to Canadian-led TF 151. That the US government did so in spite of its unhappiness over our public refusal to take any part in Iraqi leadership interdiction efforts may suggest it had few options, other than to have Canada lead. At the tactical and the operational level, however, US officers were generous in their praise of Canadian at-sea command, as were the French.

DND photo HS034012d16 by Corporal Shawn M. Kent

HMCS Iroquois leads HMCS Regina and HMNZS Te Mana in the Arabian Gulf, 6 May 2003.

Notes

- Rear-Admiral Dan Murphy, Interview with E. J. Lerhe, 2 May 2011, Esquimalt, BC, p. 8.

- Allan Thompson, “McCallum: Canadians can’t detain Iraqis at Sea: No mandate to intercept, capture or transfer them,” in The Toronto Star, 3 April 2003, p. A12. K. Toughill, (2003). Canadians Help U.S. Hunt in Gulf, in The Toronto Star, p. A01.

- R. Fife, (2003). Bush Cancels Visit to Canada-U.S. Displeased with Decision on War, Jabs from Liberals, in The National Post,pp. A1, A9.

- Janice Gross Stein and Eugene J. Lang. The Unexpected War: Canada in Kandahar. (Toronto: Viking Canada, 2007), p. 90.

- Ibid., p. 83.

- Ibid., p. 87.

- Ibid. Stein and Lang make clear that our policy of allowing Canadian exchange officers to serve with US forces in Iraq also contributed to this problem.

- Frank Harvey, Smoke and Mirrors: Globalized Terrorism and the Illusion of Multilateral Security. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), pp. 206-208.

- Stein and Lang, p. 79.

- Richard Gimblett, Operation Apollo. (Ottawa: Magic Light Publishing, 2004), pp.108-112.

- Ibid., p. 108.

- Lieutenant (USN) T. Williams and Captain (USN) P. Wisecup, (September 2002). “Enduring Freedom: Making Coalition Naval Warfare Work,” in US Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 128, No.9, (September 2002), pp. 52-55.

- K. Calder, Interview with E. J. Lerhe, 8 June 2011, Ottawa, p. 2.

- Stein and Lang, pp. 63, 80. Stein and Lang do not seem to use the term ‘double-hatted’ in its traditional sense. A ‘double-hatted’ command is normally one where its commander figuratively wears two hats. That is, he enjoys command responsibility over two-or-more organizations, and thus wears a different ‘hat’ when commanding one or the other. What Stein and Lang probably meant was that the task force was ‘dual-tasked’ in having simultaneously two missions – counterterrorism and escort. Later, they would claim that the TF 151 “…would only wear one hat- the OEF hat,” (p. 85), but for reasons that will soon be made clear, this was a less-than-convincing claim.

- Ibid., p. 80.

- Ibid., pp. 80-81.

- Ibid., p. 82.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 90.

- General Raymond Henault, E-mail to author, 11 December 2011.

- Vice-Admiral Maddison, E-mail to author, 29 January 2012, and Rear-Admiral McNeil, E-mail to author, 18 March 2012. McNeil, Interview with E.J Lerhe, 11 June 2011, Port Stanley, ON, p. 13, also covers this. .

- Henault, E-mail to author, 11 December 2011.

- Stein and Lang, p. 82.

- Henault, E-mail to author, 11 December 2011.

- McNeil, Interview, pp. 13-14.

- Henault, E-mail to author, 11 December 2011. This is corroborated by McNeil, E-mail to author, 18 March 2012.

- 1st Confidential Interview, by E.J. Lerhe, 6 Oct 2011, Ottawa, p. 8.

- Stein and Lang, p. 82.

- Henault, E-mail to author, 11 December 2011.

- McNeil, Interview, p. 14.

- 1st Confidential Interview, p. 8.

- Rear-Admiral Girouard, Interview by E. J. Lerhe, 22 February 2011, Esquimalt, BC, p. 11.

- US, “Canada Won’t Join the Military Action against Iraq without Another UNSC Resolution.” State. (03 OTTAWA 629) Ottawa Embassy Cable. (19 Mar 2003), at <http://wikileaks.ch/cable/2003/03/ 03OTTAWA747.html>, p. 2, accessed 13 May 2011.

- Stein and Lang, pp. 81-84.

- US, “ Canada Won’t Join the Military Action against Iraq without Another UNSC Resolution,” p. 2.

- Stein and Lang, p. 80.

- During the post-question period media scrum of 13 February 2003, the Defence Minister described the mission of the Canadian ships within TF 151 as “They’re working exclusively on Operation Enduring Freedom which involves the war on terrorism in Afghanistan…” See Canada, DND, “Scrum Transcript – Scrum after Question Period: John McCallum.” DGPA, 13 February 2003, at http://dgpa-dgap.mil.ca/dgpa/transcr/2003/Feb/03021305.htm, accessed 14 February 2003.

- Harvey, Smoke and Mirrors, pp. 206-08; Toughill, “Canadians Help U.S. Hunt in Gulf,” pp. A01. See also Thompson, “McCallum: Canadians can’t detain Iraqis,” p. A12.

- Stein and Lang, p. 87.

- Canada, DND, “Scrum Transcript.”

- Stein and Lang, p. 85.

- Paul Koring and Daniel Leblanc, “Canadian Will Run Persian Gulf Naval Task Force,” in The Globe and Mail, 11 February 2003, pp. A1-11.

- HMCS Ottawa successfully intercepted, boarded, and delivered to arrest the Iraqi oil smuggler MV ROAA in May 2002.

- Murphy, p. 4.

- Toughill, p. A01.

- Richard Williams, Weighing the Options: Case Studies in Naval Interoperability and Canadian Sovereignty, Maritime Security Occasional Paper. Halifax: Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, Dalhousie University, 2004, p. 82. Williams also comments favourably on Commodore Girouard’s ability to remain within his OEF tasks at his pages 76-78, and 81-83.

- Ibid. See also Gimblett, Operation Apollo, p.116.

- Paul Cellucci, Unquiet Diplomacy. (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2005), pp.141-142.

- Fife, “Bush Cancels Visit to Canada,” pp. A1, A9.

- Girouard, p. 2.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 4. The reported attack turned out to have been a false alarm.

- This process was personally confirmed by General Henault. Interview, p. 15.

- Amiral Jean-Louis Battet, Chef d’État-Major de la Marine, Letter to Admiral Buck, 15 September 2003. This translates as “in a fluid and complex environment.”

- Calder, p. 13.

- Stein, p. 87.

- Ibid.

- Harvey, Smoke and Mirrors, 206.

- Stein and Lang, 90.