Personnel Issues

DND photo AS2014-0045-006 by Sergeant Bern LeBlanc

Major Thamer leads his paratroopers to their staging area to conduct an exercise in the Oleszno training area of Poland, 4 July 2014, as part of NATO reassurance exercises.

Future Soldiers: “The Few ...” Military Personnel Trends in the Developed World

by Tom St. Denis

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Captain (ret’d) Tom St. Denis, CD, has served in three armies [Australia, Rhodesia and Canada] and two wars [Vietnam 1970–1971, Rhodesia]. His peacetime service includes three peacekeeping missions and numerous staff positions. He retired from the Canadian Army in 2010 after six years as a Public Affairs Officer with the Canadian Manoeuvre Training Centre, where he developed the Exercise Media Operations Program with Athabaska University. He has an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and is currently conducting academic work in International Relations and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary with a view to earning a PhD.

Introduction

Even in peacetime, militaries are seldom untroubled institutions. They are almost always beset by a multitude of concerns, some technical in nature, others financial or societal, and all, to some extent, political. However, a concern currently facing the militaries of the developed world approaches the existential, to wit: where will they get their soldiers?

Evidence for such a concern emanates from population studies,1 human-resources research2 and defence-technology literature.3 Taken together, the issues such works raise a military personnel problem in the developed world so acute that it threatens to undermine not only national security but also global security. These issues qualify as trends in that they are developing, and show a marked inclination to worsen. Five stand out as potentially the most deleterious: ageing and shrinking populations; increasing obesity and lack of fitness among youth; disinclination for military service; rising defence costs; and the influence of technology. These are broad-stroke trends shared more-or-less equally by all advanced societies. They were selected for study because of this and because each bears decisively on the human element. From a military perspective, the first three manifest worrisome features of developed-world populations: at once too old for military service, too unfit, and too uninterested. Rising defence costs reflect rising personnel costs,4 while technology influences military life as ubiquitously as it does civilian life.

The Trends

Ageing Populations. The trend in population ageing is a combination of both falling fertility rates and substantial increases in life expectancy.5 Since the end of the Second World War, and particularly since the 1970s, mortality among the aged has fallen continually—in some countries, the pace is actually accelerating.6 Average life expectancy in the developed world rose from 76 years in 1990 to 80 years in 2010.7 In the same period, the average fertility rate in the developed world remained steady at 1.7. The fertility rate refers to the average number of children born per woman in a given country, with the sustainability rate (at which the population replaces itself) being at least 2.1 children per woman. Among advanced countries in 2010, the average fertility rate in Germany, Italy and Japan, for example, was 1.4; only New Zealand, at 2.2, and the United States, at 2.1, achieved stability.8 (See Table 1)

| Country | Life Expectancy at Birth* | Total Fertility Rates** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2010 | 1990 | 2010 | |

| Australia | 77 | 82 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Belgium | 76 | 80 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Canada | 77 | 81 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Denmark | 75 | 79 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Finland | 75 | 80 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| France | 77 | 81 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Germany | 75 | 80 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Italy | 77 | 82 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Japan | 79 | 83 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Netherlands | 77 | 81 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| New Zealand | 75 | 81 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Russia | 69 | 69 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| Spain | 77 | 82 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Sweden | 78 | 81 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| United Kingdom | 76 | 80 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| United States | 75 | 78 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

World Bank 2012 World Development Indicators

*Life expectancy at birth is the number of years a newborn infant would live if prevailing patterns of mortality at the time of its birth were to stay the same throughout its life.

**Total Fertility Rate is the number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and bear children in accordance with the age-specific fertility rate of the specified year.

Table 1: Average Life Expectancy and Average Fertility Rates

Low fertility exerts a major influence on population size. A study of developed countries projected that, by 2050, the populations of Poland and Germany will shrink by 16 and 14 percent respectively, and that only high rates of immigration will enable the populations of Canada, Spain, Sweden, and the UK to grow.9 Overall, by 2050, the world’s population will have grown by two-to-four billion people, but because of population decline in the more developed regions, it will have grown more slowly than in the past. And it will be older.10 In an all-but-irreversible trajectory, those aged 65 years and older are becoming both more numerous than children and more numerous as a percentage of the population. By some estimates, they will soon represent one-quarter to one-third of many national populations.11

An important consequence of increasingly fewer young people and longer-living old people is a change in the composition of the population – the age structure is distorted. The normal structure is a pyramid with few very old people at the apex, and increasingly larger cohorts as the ages get younger. By way of example, until the Industrial Revolution, people aged 65 and over never amounted to more than 2 or 3 percent of the population.12 During the 19th Century, however, populations in the advanced countries began to age as fertility rates entered a period of sustained decline, until by 1950, the oldest population had about 11 percent of its members aged 65 and over. In 2000, that figure had climbed to 18 percent, and is currently projected to reach 38 percent by 2050.13 As the mid-20th Century ‘baby-boomers’ age, they swell the number of elderly at the top, while the middle section (the working-age population between 15 and 64) and the base (those aged 0 to 14) narrow considerably.14 (See Chart 1) Such a structure is not sustainable.

Rowland (2009), UN World Population Prospects, The 2000 Revision

Chart 1 – Age Structures as Fertility Rates Drop

Obesity and Lack of Fitness. Globally, the issue of obesity has reached “epidemic proportions.”15 A 2007 study found that the number of overweight and obese people is increasing exponentially in all age groups in the United States, Australia, Latin America, and many European countries.16 In the United States alone in 2009, an estimated 72.5 million Americans were obese, which equated then to 26.7 percent of the population.17 Especially disquieting is the incidence of obesity in children, which has been accelerating rapidly over the last 20 years. A World Health Organization 2005–2006 study reported overweight and obesity levels of 20 percent or more among 15-year old boys in Canada, Finland and Spain, with levels in Germany and Sweden at about 15 percent.18 (See Chart 2)

Health and Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) 2005–2006

Chart 2 – 15-year-olds overweight or obese according to BMI

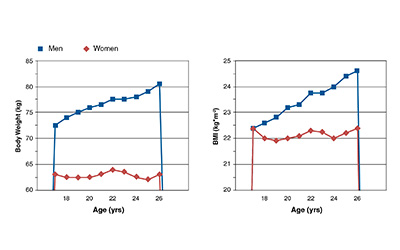

More pertinent is the incidence of overweight and obesity among military-age adults. In the United States, between 1995 and 2005, the proportion of 18-to-29-year-old individuals who were obese (i.e., with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more) increased from 10 to 18 percent. Among the cohorts studied, 18 to 54 percent of men and 21 to 55 percent of women were too overweight to enlist in the armed forces.19 In Australia in 2006, 36 percent of men and 28 percent of women of military age (18 to 24) were found to be overweight or obese. Among those just slightly older (25 to 34), the figures were 58 percent of men and 38 percent of women.20 A German study that tracked young men from age 17 to 26 discovered significant, and “monotonously” regular, increases in BMI over the period of the study, a finding the authors say “supports previous reports that overweight and obesity are established at an increasingly earlier age.”21 (See Fig. 1)

Leyk et coll., Physical Performance, Body Weight and BMI of Young Adults in Germany 2000 – 2004: Results of the Physical-Fitness-Test Study.

Figure 1 – Body Weight and BMI of Men and Women Aged 17 to 26

The situation is exacerbated by evidence of decreasing physical fitness. In a review of 85 studies on physical activity among young men from 1966 to 2009, Finnish researchers found “a disturbing worldwide trend of decreased aerobic fitness and increased obesity.”22 In the United States, a survey of young people aged 12-to-19 years discovered that approximately one-third of young males could not meet the recommended standards for aerobic fitness,23 while a German study involving more than 58,000 volunteers for the Bundeswehr reported, not only that over 37 percent could not pass the physical fitness test, but that the failure rates had increased significantly since 2001.24 (See Fig 2)

Disinclination to serve. The militaries of the developed world are, with very few exceptions, all-volunteer forces. Yet, almost universally, the propensity for military service is very low. The reasons for this are multiple, but two stand out: increasing levels of education, and a growing separation of people, not only from the military (in terms of values and ideals), but also from national institutions in general (in terms of social identity). For many years among advanced nations, there has been a noticeable trend toward higher education,25 and studies in the United States indicate a statistical correlation between the level of educational attainment and the propensity for a military career.26 Indeed, a 2003 study concluded: “The dramatic increase in college enrolment is arguably the single most significant factor affecting the environment in which military recruiting takes place.”27

Leyk et coll., Physical Performance, Body Weight and BMI of Young Adults in Germany 2000 – 2004: Results of the Physical-Fitness-Test Study

Figure 2 – Mean Total Scores and Failure Rates of the Physical Fitness Tests

Along with increased levels of educational attainment, the last several decades have also seen dramatic shifts throughout the developed world in societal values and attitudes, away from what sociologist Donna Winslow identified as “outward directedness, tradition, communalism and morality” towards “inward directedness, individualism and hedonism.”28 Such values are diametrically opposed to those crucial to all military organizations: subordination of the self to the group, obedience, acceptance of sacrifice, commonality of effort, and self-discipline. This incongruity of value systems means that the military culture no longer resonates with its parent society. Ergo, the institution’s prestige wanes, and with it, the attraction of a military career.29

The military, however, is not the only institution to find itself in conflict with changing societal values. In recent years, the influence of church, family, school, and political establishments have all been greatly weakened. In general, throughout the developed world, there is a growing rejection of uncritical obedience and subordination to institutional authorities.30 Deference and loyalty can no longer be taken for granted, and for young people, institutions, including the military, and even the nation-state, are less relevant.31 Paradoxically, these societies continue to view their armed forces favourably and believe that, in certain circumstances, military force should be used. The caveat is that military service should be performed by “someone else.”32

Rising Costs. Militaries everywhere are expensive. Those of the developed world are very expensive. The 2013 defence budget of the United States was $600 billion; that of the United Kingdom, was $57 billion (in US dollars); that of France, $52.4 billion; Japan, $51 billion; and Germany $44.2 billion. Even among the lesser powers, the amounts are considerable: Australia, $26 billion; Canada $16.4 billion; the Netherlands, $10.4 billion.33 Roughly half (and more) of these expenditures cover personnel costs: salaries, benefits, and, in some cases, pensions.34 Modern military professionals are well-paid members of the middle class, “with perquisites and benefits comparable to, and, in many ways, superior to, those members of a large corporation.”35 The authoritative International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) reports that the US military pays “substantially more than the private sector,” noting that “[w]hen compared to workers in the civilian sector ... on average armed forces personnel earn more than 90% of civilian employees.”36 The situation is broadly comparable in Britain,37 Australia, and Canada,38 and while salaries and benefits are a good deal lower in Europe’s armed forces, the Europeans tend to spend much larger proportions of their defence budgets on personnel.39

Non-personnel spending (i.e., ‘materiel’) covers everything the armed forces use, from the mundane to the exotic. Increasingly significant proportions of these monies are being allocated to technology, specifically to information and communication technology. Since the First Gulf War in 1991, the US military has become ever-more technology-driven in pursuit of a “techno-centric vision of future warfare.”40 The most revolutionary and expensive element of this transformation concerns operationalizing the concept of net-centric warfare, “ … a hugely ambitious programme to create a Global Information Grid (GIG) integrating all US military and [Department of Defense] information systems into one seamless and reliable super-network.” While the whole network is not expected to be fully developed until around 2020, just putting the GIG’s core capabilities in place by 2010 was estimated to cost some $20 billion.41

Even in the developed world, no military can hope to match the US investment in military-related technology, and so, efforts to emulate the American model tend to be relatively modest in scope.42 Nevertheless, even modest efforts entail costs, the first of which is the expense of recruiting and retaining well-qualified personnel. High-tech militaries may require fewer people, but those people are invariably more costly. Then, there is the ever-growing cost of training even the lowest ranking soldiers.43 Militaries sometimes find it more cost-effective to concentrate on simply operating the equipment and weapons, and contracting out their maintenance to civilian firms.44

DND photo IS2014-1008-04 by Sergeant Matthew McGregor

An Air Vehicle Operator with 4 Air Defence Regiment operates the ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicle using a pilot control console during Exercise Maple Resolve, CFB Wainright, 30 May 2014.

DND photo IS2014-1008-06 by Sergeant Matthew McGregor

Launch of the ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicle during Exercise Maple Resolve.

High-Tech Militaries. Advanced militaries aggressively pursue cutting-edge technology—largely information-processing, but also precision-guided munitions. One significant impetus for this is the requirement to keep casualties low. Equally important, as recruiting pools grow shallower and qualified personnel more expensive, investment in technology enables militaries to substitute capital for labour.45 High-tech weapons (i.e., pilotless drones and cruise missiles) are more efficient than other means at projecting force to remote locations, while also limiting non-combatant casualties. They negate the need for large numbers of troops on the ground, and greatly reduce the hazards of combat for those who are deployed. Indeed, the transformation of the American military following the Vietnam War was predicated on just such strategic needs: “the need for power projection, quick wins, low casualties, and the flexibility to move from one theatre to another.”46

America’s allies have similar needs for short wars and few casualties, but more importantly, they see future combat commitments almost exclusively in terms of US-led coalitions. Therefore, maintaining interoperability with the US military is a major imperative,47 and likely to be the primary focus of the British, French, Canadian, and Australian militaries. Among the majority of European allies, the challenges are more prosaic. After two hundred years as conscription-based organizations, their militaries are struggling to turn themselves into professional armed forces, and, as yet, “cannot fully exploit the potential of the new technologies.”48 On the other hand, even the most advanced allies continue to lack some components of effective military power— i.e., sufficient stocks of precision weapons, as evidenced in the air campaign against Libya – and consequently, the technological gap between the US and other militaries is likely to increase in the immediate future, not to diminish.49

Mitigating Measures

Ageing Populations. There are not many ways to mitigate the effects of ageing and shrinking populations on military recruiting. Of course, the most telling solution would be to reverse the decline in fertility rates. Unfortunately, there is currently no prospect for this.50 In any case, fertility rates would have to increase dramatically, and remain consistently high, to have any appreciable effect, and even then, ageing would only be slightly slowed.51 Moreover, to get populations to start replacing themselves, childlessness and one-child families would have to be actively discouraged, or there would have to be a sustained increase in the percentage of families with three-or-more children. This flies in the face of numerous developed-world social conditions working in the opposite direction. Parents with few children are seen as ‘better parents’ because they can devote more time and resources to each child; poverty-reduction programs curb fertility by encouraging smaller families among the poor; and finally, Western women are gaining in gender equality and economic independence, both of which result in lower fertility rates.52

Another strategy is to raise the age at which people typically retire, and already, many governments are abolishing mandatory retirement ages.53 But while this may be a viable strategy in the civilian world, most militaries retain a compulsory retirement age for a very good reason: some tasks, notably those of the combat arms, demand the stamina and strength of youth. On the other hand, many armed forces have increased the age at which volunteers can apply to join. For example, in the UK, the maximum age was increased from 26 to 33,54 and in the US, from 35 years to 42.55

Alternatively, militaries can search for new sources of young people, and two groups with relatively high fertility rates immediately present themselves: established minority communities, and new arrivals. In terms of the first, particularly in Canada, population growth is far outstripping that of the dominant Caucasian group, and it offers a diverse military-age pool from which to draw.56 In terms of the second, it is estimated that to 2050, about two million people a year will migrate from less-developed to developed countries at a more-or-less steady rate.57 Yet, studies have shown that only massive and sustained increases in immigration would have any effect upon slowing or reversing population ageing.58

DND photo AS2014-0042-001 by Sergeant Bern LeBlanc

Paratroopers from 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, go for a 10 kilometre run to celebrate Canada Day at Ziemsko Airfield, Poland, 1 July 2014.

Obesity and Lack of Fitness. As with ageing, there are not many options when it comes to obesity, although there may be with the quite separate issue of the general unfitness of youth. Militaries put great store in physical appearance, which is perceived to indicate general fitness, and to contribute to how the military is viewed by the public. Appearance also influences individual self-esteem and acceptance by peers.59 And so, militaries are generally loathe to contemplate any relaxation of standards. In 2006, the Australian Defence Forces did revise the entrance standard to accept overweight applicants because the original standard severely limited the number of potential recruits.60 However, American researchers regard such a policy as both “simplistic” and expensive, since obesity costs the US military over $1.2 billion a year in higher health spending and lower productivity. It was found that 80 percent of recruits who exceeded the weight-for-height standards but were accepted on waivers left the military before completing their first term of enlistment.61

One strategy to deal with obesity and general unfitness is simply to employ technology in lieu of humans. More and more militaries are, in fact, doing this through the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for reconnaissance, and even for combat. Other robotic devices are substituting for soldiers in bomb-disposal, improvised explosive device neutralization, and mine-clearing chores. Navies, too, are researching ways to utilize technology instead of humans. Capital ships are being designed to function with fewer sailors, primarily to reduce acquisition and operating costs,62 but also to allow for more selective recruiting. Air forces have been working with missile technology for several decades.

Disinclination to serve. How does a liberal democracy fill the ranks when the bulk of its citizens choose not to volunteer? Once again, one option is to look to immigrants. However, immigrant communities often regard the military as a low-status career option. In such communities, education is highly valued, and, as already noted, with higher education comes a diminishment in the propensity to serve.63 With few takers at home, militaries may choose to follow the example of large corporations and go abroad to recruit. To answer the need for fit young males for ground combat roles, researcher George Quester cites the examples of Britain’s Gurkhas and France’s Foreign Legion, both of which recruit specifically for infantry employment. To find technological talent, he suggests emulating the firms of Silicon Valley.64

Another solution is to institute compulsory military service. Many in favour of conscription stress the concept of duty, along with the requirement that the military represent the entire country in the same manner that the central government must represent the nation as a whole. If shared by all the able-bodied, military service would not be a career, but a duty of citizenship.65 The key is that any system must draw fairly from all segments of society,66 and it is at least arguable that a universal system that conscripts all citizens, as Israel does, is more equitable than a system of selective service in which all are eligible but only a few are chosen. Conscription opponents point out the inherent dilemmas. Politically, there is little-to-no support for conscription where it does not currently exist—when asked, 67 percent of American college students opposed reinstating the draft67—an antipathy mirrored in Europe, where many countries have only recently abolished conscription.68 Administratively, it would be difficult if not impossible to implement a system free of abuses, exemptions, and inequalities. Economically, conscription is far from the most efficient method of producing the means for national defence. And militarily, it depletes the quality of both personnel and operational effectiveness.69 Conscripts typically serve for only two years, and modern soldiers need up to three years to be judged fully competent in combat and combat support skills.70

DND photo IS2014-1013-08 by Sergeant Matthew McGregor

Non-live fire training activities near Kaneohe Bay, Marine Corps Base Hawaii, during Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC), 27 June 2014.

Rising Costs. For any government intent upon realizing savings with minimum delay, slashing the number of people on the payroll is the quickest way to an immediate effect. The first result is a reduction in the number of salaries that have to be paid, but there are longer-term savings in the benefits and allowances not claimed and the pensions not taken, plus the associated health and welfare costs for which the government is no longer responsible. This is largely the thinking behind the force reductions currently underway in militaries across the developed world. Proposed reductions will shrink the US Army from 500,000 to between 440,000 and 450,000,71 while British reductions have already produced the smallest army “since the early 1930s.”72

Downsizing, however, does foster ever-greater military cooperation and interdependence. Even before joining the coalition in Afghanistan, European forces had joined in multinational deployments to the Balkans and to Africa “in order to sustain and develop joint security partnerships.”73 Consequently, “European armed forces are increasingly interdependent and inter-operable at a level that would have been inconceivable before the 1990s.”74 The result is pragmatic. In a continuing environment of declining defence spending, integration is just about the only way to retain an appreciable level of military capability.75 However, the danger is that countries will satisfy financial imperatives by “salami-slicing” their capabilities to the point where they maintain only “Bonsai” armies: “small and aesthetically pleasing, but effectively useless.”76

In a bid to preserve their ‘teeth-to-tail’ ratio, many countries have turned to private military companies (PMCs).77 One part of this phenomenon is the largely-invisible outsourcing of such functions as clerical administration, vehicle maintenance, computer network control and the like to reduce the number of military or government employees in these occupations. PMCs are more visible on overseas missions, where they are responsible for many camp operations, from initial set-up of living quarters and administrative facilities, to staffing the mess halls, to managing the water supplies.78 More highly paid contractors, those with military or police experience, train host-nation military and paramilitary personnel, guard VIPs, and carry out convoy protection. The most highly paid are those associated with very sophisticated weaponry, who are either seconded from or hired by the manufacturers to maintain, and even operate, weapons for the military.79

It has been suggested that political leaders will find it increasingly attractive to privatize military ventures, considering both the financial costs and the ‘shadow price of death’ attached to committing national troops to dangerous missions. Employing private companies would obviate not only the ‘body bag syndrome,’ but also the need to develop the level of popular consensus necessary to support a national effort.80 There are, however, caveats to the employment of PMCs when it comes to actual fighting. As one study notes: “... the endemic uncertainty of virtually any military situation makes economically efficient contracting between the state and a private military firm inevitably problematic”81—in other words, given the vicissitudes of warfare, how is the client to know he is getting his money’s worth? What are the criteria for progress, for success, and are these equally understood by both sides? Also, PMCs pay considerably better than national militaries for comparable skill levels,82which serves to siphon off trained and experienced personnel.

High-Tech Militaries. Given the unceasing integration of technology into military affairs, perhaps the only mitigating measure is to regard military technology with some skepticism. There are those, like Stephen Biddle, who believe that the brilliance of military technology has been oversold. He holds that trading “mass for speed and close combat for stand-off precision” worked only against unskilled Taliban and the incompetent Iraqi military, and became demonstrably less effective once trained foreigners replaced the Taliban, and Iraqi insurgents learned what they were up against.83

Michael Mosser sees a problem in what amounts to blind faith in technology. He states that “American society believes in its technology and believes its technology can be adapted to overcome any obstacle,” and that this attitude carries over wholesale into the US military.84 As a consequence, believing in technological ‘quick fixes’ leads to an uncritical preference for technological solutions “even when ‘better’ (i.e., cheaper, more robust, but less ‘sexy’) alternatives present themselves.”85 Mosser worries that “[a]pplying net-centric, techno-wizardry solutions to complex, anthropologically driven questions may be generating the right answers to the wrong questions.”86

Conclusions

What do these several trends foretell? First of all, that for military recruiters in the developed world the future is not promising. They will be engaged continuously in a battle with their private-sector counterparts for an ever-shrinking pool of qualified young people, and that battle will be in no way equal. Militaries in the industrialized world are severely disadvantaged as employers in that their values and ideals are diametrically opposed to those most cherished by the very people they are trying to attract. In order to align themselves with the tenets of their target audiences, to be more relevant to them, militaries would have to abnegate the very traits that make them effective institutions. It would amount to self-immolation.

The militaries’ values and ideals are at least within their control. Their other disadvantages are beyond their abilities to mitigate or affect. Concerning ageing populations, they might try to retain experienced individuals longer in service, and even accept older recruits, but as Christopher Dandeker as pointed out, the armed forces are “quintessentially a young people’s organization.”87 Against the problems of obesity and general unfitness, militaries can and do strive—but often in vain, and at great expense. The problem begins long before young people reach military age, which is why the retired US generals’ and admirals’ lobby group, Mission Readiness, has called for the nation’s schools, where children regularly buy their breakfast, lunch and snacks, to be “properly managed” in order to become “instrumental in fostering healthful eating habits.”88 This may very well be the first step in a move to securitize childhood health and fitness, given that the same organization has labelled the epidemic of obesity “a potential threat to our national security.”89

Another disadvantage is that militaries do not control their funding, and cannot adjust their wage and benefits packages in order to compete with the private sector. Even if they were to expand their recruiting efforts to include foreign countries, there, too, they would be in unequal competition with private firms. The unassailable fact is that in the well-educated, affluent West, very few youth evince any desire to pursue a career in what they see as an archaic, anti-individual institution. In time, this could lead to conscription again being seriously considered as the only option short of foregoing military forces entirely.

In the matter of military costs, the operative word in defence ministries everywhere is ‘reduction.’ Fortunately, this is occurring at a time when, for sound political, strategic, and financial reasons, the Western allies’ military ventures are almost invariably thought of in terms of coalitions, usually ‘US-led.’ And this, in turn, strengthens military integration as an economical means for them to possess modern military capabilities, albeit on a restricted scale. Further savings might be realized by outsourcing some military functions to private firms, largely in the realm of camp services or ‘policing duties’ short of major combat. But one of the strengths of such enterprises— relatively high salaries—is also a weakness. No for-profit company can afford to pay high salaries to the numbers required for high-intensity close-quarter fighting for sustained periods. Thus, private military firms will always be a circumscribed option.

In light of these seemingly-intractable problems, and given the developed world’s propensity always to expect technological solutions, Western militaries understandably seek salvation in technology. The promise it holds is that a sufficient application of the right kind of software and hardware can substitute for the people that armed forces do not have, do not want or cannot afford, and for the funding they are not given. But technology has a number of downsides. It is enormously expensive in a host of ways, and while it can perform some tasks spectacularly well on the battlefield, close-quarter combat will always be the preserve of vulnerable humans wielding short-range personal weapons. I believe Wenke Apt is quite right in saying that “armed conflicts will continue to be a human endeavour,”90 and so humans, in appropriate numbers, will always be the essential element in war. Which returns us to the original question: Where are the soldiers going to come from?

DND photo IS2014-1013-12 by Sergeant Matthew McGregor.

More training activities during RIMPAC, 27 June 2014.

Notes

- For example: Tracey A. LaPierre and Mary Elizabeth Hughes, “Population Ageing in Canada and the United States,” in International Handbook of Population Ageing (Vol. 1), Peter Uhlenberg (ed.), (Springer, 2009), pp. 191-230.

- For example: T. Szvircsev and C. Leuprecht (eds.), Europe without Soldiers? Recruitment and Retention across the Armed Forces of Europe, (Montreal and Kingston: Queen’s Policy Studies Series, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012).

- For example: Terry Terriff, Frans Osinga, and Theo Farrell, A Transformation Gap? American Innovations and European Military Change, (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Security Studies, 2010).

- The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance, (London: Routledge, 2014), pp. 37, 64 and 205.

- Christian Leuprecht, “Socially Representative Armed Forces: A Democratic Imperative” in Europe Without Soldiers? p. 43.

- Kaare Christensen, Gabriele Doblhammer, Roland Rau, and James W. Vaupel, “Ageing Populations: The Challenges Ahead,” in The Lancet 374: 9696 (2009), p. 1196.

- World Bank, World Development Indicators, (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Washington, D.C., 2012). Digitized by Google, and available online at Google Scholar, p. 128.

- Ibid., p. 112.

- Wenke Apt, “The Socio-Demographic Context of Military Recruitment in Europe: A Differentiated Challenge,” in Europe without Soldiers? p. 67.

- Joel E. Cohen, “Human Population: The Next Half Century,” in Science 302: 5648 (2003), p. 1172.

- George H. Quester, “Military Recruitment: Surprising Possibilities,” in Parameters 35: 1 (2005), p. 27.

- Peter G. Peterson, “Gray Dawn: The Global Ageing Crisis,” in Foreign Affairs 78: 1 (1999), p. 43.

- Donald T. Rowland, “Global Population Ageing: History and Prospects,” in International Handbook of Population Ageing (Vol. 1), p. 37.

- Apt, p. 68.

- R. McLaughlin and G. Wittert, “The Obesity Epidemic: Implications for Recruitment and Retention of Defence Force Personnel,” in Obesity Reviews 10 (2009), p. 693.

- Heikki Kyrolainen, Matti Santtila, Bradley C. Nindl, and Tommi Vasankari, “Physical Fitness Profiles of Young Men: Associations Between Physical Fitness, Obesity and Health,” in Sports Medicine 40: 11 (2010), p. 913.

- Vanessa M. Gattis, Obesity: A Threat to National Security? (Thesis for Master of Strategic Studies Degree from the US Army War College: Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, 2011), p. 1.

- Apt, p. 74.

- Grover Yamane, “Obesity in Civilian Adults: Potential Impact on Eligibility for US Military Enlistment,” in Military Medicine 172: 11 (2007), p. 1160.

- McLaughlin and Wittert, p. 693.

- D. Leyk, U. Rohde, W. Gorges, D. Ridder, M. Wunderlich, C. Dinklage, A. Sievert, T. Ruther, and D. Essfeld, “Physical Performance, Body Weight and BMI of Young Adults in Germany 2000-2004: Results of the Physical-Fitness-Test Study,” in International Journal of Sports Medicine 27 (2006), p. 645.

- Kyröläinen et al, p. 907.

- Ibid., p. 909.

- Ibid., p. 911.

- Apt, p. 71.

- Ricard M. Wrona Jr., “A Dangerous Separation: The Schism Between the American Society and its Military,” in World Affairs 169: 1(2006), p. 33.

- Apt, p. 74.

- Donna Winslow, “Canadian Society and Its Army,” in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 4 No. 4, (2004), p. 19.

- Szvircsev Tresch, p. 147.

- Apt, p. 76.

- Winslow, p. 19.

- Wrona, p. 31.

- The Military Balance, passim.

- Vincenzo Bove and Elisa Cavatorta, “From Conscription to Volunteers: Budget Shares in NATO Defence Spending,” in Defence and Peace Economics 23: 3 (2011), p. 278.

- Eliot A. Cohen, “Change and Transformation in Military Affairs,” in The Journal of Strategic Studies 27: 3 (2010), p. 404.

- The Military Balance, p. 37.

- Alasdair Smith, (Chair), Armed Forces’ Pay Review Body: Forty-Second Report, (London: The Stationery Office Ltd., 2013), p. 8.

- Major Mark N. Popov, A Confluence of Factors: Canadian Forces Retention and the Future Force, (Thesis for Master of Defence Studies from the Canadian Forces College: Toronto, Ontario, 2011), p. 16.

- The Military Balance, p. 64.

- Theo Farrell, “The Dynamics of British Military Transformation,” in International Affairs 84: 4 (2008), p. 784.

- Ibid.

- Theo Farrell, Sten Rynning, and Terry Terriff, Transforming Military Power Since the Cold War: Britain, France and the United States, 1991-2012, (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 3.

- John B. Sheldon, “The Rise of Cyberpower,” in Strategy in the Contemporary World: An Introduction to Strategic Studies (Fourth Edition), John Baylis, James J. Wirtz, and Colin S. Gray (eds). (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 316.

- Eliot Cohen, p. 404.

- Leuprecht, p. 47.

- Eliot Cohen, p. 398.

- Farrell, p. 782.

- Eliot Cohen, p. 400.

- Ibid.

- John Bongaarts, “The End of the Fertility Transition in the Developed World,” in Population and Development Review 28: 3 (2002), p. 439.

- LaPierre and Hughes, p. 203.

- Rowland, p. 62.

- Christensen et al., p. 1205.

- Christopher Dandeker and David Mason, “Echoes of Empire: Addressing Gaps in Recruitment and Retention in the British Army by Diversifying Recruitment Pools,” in Europe Without Soldiers? p. 217.

- Yamane, p. 1160.

- Franklin C. Pinch, “Recent Trends in Military Sociology in Canada,” in Armed Forces and International Security: Global Trends and Issues, Jean Callaghan and Franz Kernic (eds.), (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2003), p. 84.

- Petersen, p. 46.

- LaPierre and Hughes, p. 202.

- McLaughlin and Wittert, p. 693.

- Jonathan Peake, Susan Gargett, Michael Waller, Ruth McLaughlin, Tegan Cosgrove, Gary Wittert, Peter Nasveld, and Peter Warfe, “The Health and Cost Implications of High Body Mass Index in Australian Defence Force Personnel,” in BMC Public Health 12: 451, (2012). Published online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/451 , p. 452.

- John Cawley and Johanna Catherine Maclean, “Unfit for Service: The Implications of Rising Obesity for US Military Recruitment,” in Health Economics 21 (2011), p. 1363.

- D.E. Anderson, T.B. Malone, and C.C. Baker, “Recapitalizing the Navy Through Optimized Manning and Improved Reliability” in Naval Engineers Journal 110: 6 (1998), p. 61.

- Dandeker and Mason, p. 219.

- Quester, p. 32.

- Ibid., p. 34.

- Wrona, p. 34.

- Ibid., p. 30.

- Edwin R. Micewski, “Conscription or the All-Volunteer Force?: Recruitment in a Democratic Society,” in Who Guards the Guardians and How: Democratic Civil-Military Relations, Thomas C. Bruneau and Scott D. Tollefson (eds.), (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006), p. 209.

- Wrona, p. 34.

- Lawrence J. Korb and Sean E. Duggan, “An All-Volunteer Army? Recruitment and Its Problems.” in Political Science and Politics 40: 3 (2007), p. 467.

- Thom Shankar & Helene Cooper, “Pentagon Plans to Shrink Army to Pre-World War II Level,” New York Times, 23 February, 2014.

- Dandeker and Mason, p. 217.

- Anthony King, The Transformation of Europe’s Armed Forces, (Cambridge and New York. Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 27.

- Timothy Edmunds, “The Defence Dilemma in Britain,” in International Affairs 86: 2 (2010), p. 381.

- Ståle Ulriksen, “European Military Forces: Integration by Default,” in Denationalisation of Defence: Convergence and Diversity, Janne H. Matlary, and Øyvind Østerud (eds.), (Aldershot (UK) and Burlington (USA): Ashgate Publishing Company, 2007), p. 67.

- Farrell et al, p. 297.

- Ulrich Petersohn, “Sovereignty and Privatizing the Military: An Institutional Explanation,” in Contemporary Security Policy 31: 3 (2010), p. 531.

- Thomas E. Ricks, “The Widening Gap Between the Military and Society,” in The Atlantic Monthly 280 (1997), p. 70.

- Christopher Coker, “Outsourcing war,” in Cambridge Review of International Affairs 13: 1 (1999), p. 111.

- Eric Fredland and Adrian Kendry, “The Privatization of Military Force: Economic Virtues, Vices, and Government Responsibility,” in Cambridge Review of International Affairs 13: 1 (1999), p. 148.

- Ibid., p. 162.

- Todd Woodruff, Ryan Kelty, and David R. Segal, “Propensity to Serve and Motivation to Enlist among American Combat Soldiers,” in Armed Forces & Society 32: 3 (2006), p. 363.

- Stephen Biddle, “Iraq, Afghanistan, and American Military Transformation,” in Strategy in the Contemporary World, p. 248.

- Michael W. Mosser, “The Promise and the Peril: The Social Construction of American Military Technology,” in The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, 11:2 (2010), p. 101.

- Ibid., p. 94.

- Ibid., p. 101.

- Dandeker and Mason, p. 215.

- William Christeson, Amy Dawson Taggart, and Soren Messner-Zidell, Too Fat to Fight: Retired Military Leaders Want Junk Food Out of America’s Schools. A report prepared for Mission: Readiness, Military Leaders for Kids, (New York and Washington, D.C. 2010), Introduction.

- Ibid., p. 1.

- Apt, p. 64.