Book Reviews

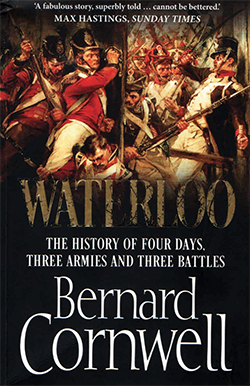

Waterloo – The History of Four Days, Three Armies, and Three Battles

by Bernard Cornwell

London: William Collins, 2014

352 pages, $24.99

ISBN: 978-0-00-758016-4 (Trade Paperback)

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Reviewed by Mark Tunnicliffe

The battle of Waterloo is famous for a lot of things – not least of which are a series of (usually misquoted) Wellington bons mots. One of these, in a letter the Duke wrote a month after the battle, noted that “The history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.” Putting together these recollections into some kind of coherent account of the seminal event of the early-19th Century has presented a challenge to historians and soldiers over the past two hundred years. Certainly, a narrative of the event, at all levels, from the personal to the strategic, has all the makings of a great plot line – portent, drama, personalities, mistakes, and recovery, and perhaps most tellingly, a race against time (or for it?). Perhaps then, on the bicentennial of the Battle of Waterloo, it is fitting that a novelist should try his hand at making sense of this particular ‘ball.’

Bernard Cornwell is probably one of the best choices for the task. Famed for novels following his character Richard Sharpe in the Peninsular War, as well as other historical series covering the Hundred Years War and the campaigns of Alfred the Great, Cornwell has gained a large following of devoted readers. His meticulous research into the major players, the social mores, weapons systems and tactics, and perhaps most importantly, his personal explorations of the battle sites which are the focus of his novels, make them convincing reading. Cornwell has preceded his history of the Waterloo battle with a novel in the Sharpe series (Sharpe’s Waterloo – London: HarperCollins 1990), the research for which has provided him with an excellent basis for his first essay at branching out from fiction to fact. The question for the reviewer largely becomes: How well does he manage this transition, and what does Cornwell add to the already voluminous history of the events of 15-18 June 1815?

Cornwell’s account quickly betrays his penchant for personally studying the battlegrounds that are a focus of his writing, as well as his pro-British sympathies. Indeed, the frontispiece of this well-illustrated book consists of a Turner painting (1833) of the battlefield, which exaggerates the depth of the valley separating the French and Allied armies, but does underline the potential for Wellington’s favourite defensive strategy of shielding his troops on a reverse slope. Cornwell beats this point home repeatedly, not only in describing the tactic, but in pointing out Blucher’s failure to use it, contrary to Wellington’s advice and Napoleon’s disparaging remarks about that “tired old tactic.” Cornwell also highlights Wellington’s strongpoints (the farms of Hougoumont and La Haie Sainte), and the critical positions they occupied in anchoring Wellingtons right and centre positions, although in his somewhat hagiographic description of Wellington’s generalship, Cornwell does not make much of the Englishman’s failure to properly prepare La Haie Sainte as a fortified redoubt.

Cornwell’s account of the battles of 16-18 June 1815 comes across as a rather English affair, leaving a reader familiar with both his books on the subject to wonder to what extent this history has been influenced by his earlier novel. The missteps of the Prince of Orange (Commander of Wellington’s I Corps, and referred to by Cornwell as ‘Slender Billy’) receive a greater emphasis in Cornwell’s historical account than other writers provide. The prince’s exposure of his infantry to decimation by cavalry by disposing them in line on at least two occasions was certainly damaging, but while this event was central to the story line in Sharpe’s Waterloo, it probably was not as significant as Cornwell makes it out to be. Indeed, another Dutchman’s disobedience probably retrieved Wellington’s situation prior to Quatre Bras. ‘Slender Billy’s’ experienced Chief of Staff, Major General Rebeque, and his second (Dutch) division commander, Lieutenant General Perponcher-Sedlinkitsky, determined that the order to abandon the critical Quatre Bras crossroads was a mistake, and held the position long enough to permit Wellington to reverse himself and stabilize the situation – a decision briefly acknowledged by Cornwell.

Similarly, the Prussians, largely in the form of Prussian army commander Blucher’s chief of staff General Augustus von Gneisenau, come in for criticism for the latter’s mistrust of Wellington and an impression of duplicity on the part of the British that, according to Cornwell, “defies imagination.” However, given that the British, in the person of their rather-erratic Foreign Secretary Castlereagh, had been undermining Prussian ambitions at the Congress of Vienna, and had signed a secret treaty with France to oppose Prussia, such suspicions are not at all surprising. Indeed, as Gneisenau had obtained a copy of the treaty from an arrested French official, and had written to Wellington, who was to replace Castlereagh, for an explanation only a few months before the two nations found themselves allies against the French, Blucher’s trust in Wellington is probably more surprising than Gneisenau’s mistrust. The political aspects of this campaign are not really explored in Cornwell’s account.

That said, the narrative of the battles, and Waterloo in particular, demonstrate Cornwell’s mastery of storytelling. His prose is that of the novelist, and his habit of mixing the present and past tenses in a single paragraph serves to bring immediacy to the account, or to irritate the reader, depending upon the latter’s preferences. His character development is that of a polished novelist, and it also adds to the flavour of his narrative and to the rationale for the various decisions made during the press of battle. Cornwell’s management of the battle timeline is also both pragmatic and a useful storyteller’s device. Instead of describing the siege at Hougoumont, the attack on Wellington’s centre, and the progress of the Prussian army from Wavre as sequentially-separate events, as is often done, Cornwell narrates them in temporal order as the day progresses. This is both a natural sequencing of events, and a compelling device for heightening the tension of the narrative.

The book is also very well supported with period illustrations of the major events and principal actors, which blend well with Cornwell’s narrative. Even more useful to the reader are the well laid-out maps and diagrams which preface most of the chapters to aid the reader in understanding the spatial development of events. It is not, however a ‘history’ written with copious footnotes and dry prose. Instead, individual accounts are embedded in the text as a device for bringing out the human side of a very cataclysmic event. Academic analysis is largely absent, perhaps leading to some of the omissions noted above – the reasons for commanders’ prejudices, the necessities of allied diplomacy, and alternative post-battle strategies – but this is probably not the intent of Cornwell’s undertaking.

He brings the novelist’s approach to the battle, and this is perhaps something by which the extensive literature on the battle could indeed profit. As Cornwell noted in his preface to Sharpe’s Waterloo, there is enough ‘cliff-hanging’ drama in the reality of the events of 18 June 1815 that no novelist’s plot line needed any competing embellishment. For those readers wanting an academic, analytic account of the history of one of the Western world’s most famous battles, there are plenty of better references. For those, however, who desire a clear, dramatic telling of the day’s events, Cornwell’s Waterloo is well-recommended. Indeed, one might pose a minor quibble: the subtitle to his account might more accurately be stated as ‘the story of four days…’ rather than as their ‘history.’ And if his account may appear to some readers as rather English-centric – this perspective is perhaps no less valid than any other view of that rather confusing ‘ball’ at Waterloo…

Mark Tunnicliffe served for 35 years in the Canadian Navy, and another five with Defence Research and Development Canada, before retiring in 2013. He now serves as a volunteer interpreter and researcher at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.