Views and Opinions

Cal Sport Media/Alamy Stock Photo/K6D619

Chicago Bears defense line up against the Atlanta Falcons offense during an NFL game, 10 September 2017.

Explaining Cultural Difference between Professional Organizations: A Sports Analogy to Start Further Discussion

by Caleb Walker

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

NFL teams are horrible at Rugby – and Rugby teams are horrible at American Football

In every great army mess – there are professional discussions of the following problem – what should we train to fight? Big or small wars? Counterinsurgencies or conventional fights? Can we be good at every spectrum of conflict? The intent of this article is to continue to spur that professional discussion. It describes ‘why we are who we are.’ I want all ranks in the Canadian Army to be able to use this article as a primer for further discussion. As we move away from Kandahar Afghanistan – its hard lessons, its tough fights – we need to keep discussing what makes a counterinsurgency different from other fights in which we may participate.

Why are armies that fight counterinsurgencies different to those that fight conventional wars? Simply put, it is because the highest level professionals – in whatever chosen profession – need to operate differently from those engaged in a different profession. The architect operates differently than a lawyer, and the physician operates very differently than the engineer. I will use a sports analogy to further illustrate the point:

Rugby Union and American Football played in the National Football League (NFL) are two different sports. The differences are in the equipment that the players wear or use; their skills and training; and lastly, the culture of the professional teams that make them successful. The ‘culture’ embraces the ideas, customs and behaviours of the particular team. It includes the ‘way things get done around here,’ and it is built by the underlying assumptions1of the team. The professional team culture is built over decades.

The culture or team ‘personality’ is different, not just between sports, but also between teams of the same sport. Each team has a different approach: to the media; the team’s priorities; leadership within the team; discipline; and the relationship with the boss – the coach. The two sports are managed very differently on the field. Football has headsets allowing constant communication. The head coaches, assistant coaches, quarterback and a defensive captain are reacting to constant decisions on the sideline. In football, there is command and control on the field. In rugby, the coach stands on the side line – or sits in the stands – and provides specific direction. In the middle of the game, the rugby players are fighting their own battle. Decisions are made by the team Captain. The offense is arranged by the ‘first-five.’ The relationship is fundamentally different. The assumptions on who makes the decisions are different.

In football, players often talk about hurting the other team – not injuring their opponent – but physically dominating them. They want the other team to flinch. The linebackers want the quarterback to hear them coming and impede his decision making. It is a physically demanding contact sport. Rugby players want to dominate the other team as well. But they also want to create gaps and exhaust the defence. Rugby never stops and the players are constantly moving and adjusting to broken plays. They want to be faster, control the ball, possession and territory. The assumptions on how to win the game are different.

How long, if ever, would it take the best NFL team to win the World Cup in Rugby? The other way? The change would require a few steps: the first would be appropriate equipment so that a rugby player could be expected to take a tackle from a 260 pound NFL linebacker; the second might be a recruitment drive to get different talent into the team; the third is fitness, skills and a game plan that will work for the new sport; and one of the last aspects, that could take years or decades, would be to change the culture of the team, the coaches, the management, and the fans in order to win in the new sport.

Could a team play both? Not professionally. There are several players that have the capacity to play aspects of each game well. They can even play multiple sports at the highest level. But they are gifted athletes. A professional team requires time to build its culture. The way they structure their meetings, make decisions, run practises, improve the team and interact with the coaches.

Would you ever make a Football team play professional Rugby? Probably not, but the Canadian Armed Forces – for a variety of reasons, and mostly out of its control – might be asked to participate in another professional role. We just need to remember, NFL teams are horrible at Rugby – and Rugby teams are horrible at American Football.

Oscar Max/Alamy Stock Photo/D9M9HA

‘The Beast’ Mtawarira breaking free from a maul during the Castle Larger Rugby Test between South Africa and Scotland, at Mbombela Stadium in Nelspruit, South Africa, 15 June 2013.

Introduction

The Canadian Army is focused upon a conventional theatre of operations. The culture of an army that is focused upon a conventional war makes fighting a counterinsurgency very difficult. The scope of this article will be to discuss the culture of those two types of fighting. It will conclude that the Canadian Army cannot be expected to master the fight in a counterinsurgency without a significant cultural change. And we cannot forget that a culture change takes time…

Organizational Culture

Defining organizational culture is quite difficult as it is an abstract concept. The best the way to imagine culture is to use expert on organizational development Edgar Schein’s description from Organizational Culture and Leadership Defined, in which he maintains that “…culture is to a group what personality or character is to an individual.”2 We understand culture at the ethnic or national level, but we find it difficult to look at smaller groups and consider their culture. We understand that there is a cultural difference between people that live in Alberta and Afghanistan. We understand that the cultural difference between police officers and doctors. That is because their culture, behaviours and assumptions are very different. It is when the culture is more familiar, that we find it difficult to grasp the important differences.

To have a culture one needs shared experiences and assumptions. Schein believes that any organization that has a shared history has a culture. This culture is strengthened the longer the organization is together, and is further strengthened by the “emotional intensity” of the organizations shared experiences.3 National militaries around the world have a culture. The longer that an organization exists, the more assumptions define its behaviours.

Culture is often associated with ‘values,’ and people ask if an organization has ‘the right culture.’ Schein believes that this is the wrong way to look at culture. There is no right or wrong culture. The culture will reflect how the organization achieves its goals and how it interacts with the environment. Culture is also often associated with behaviours, but that is also incorrect. Behaviours are the ‘end product’ of a culture. Culture is built from the assumptions that the group makes on how their organization is supposed to work. This article will discuss the behaviours of the different military forces and then discuss what assumptions or culture generates those behaviours.

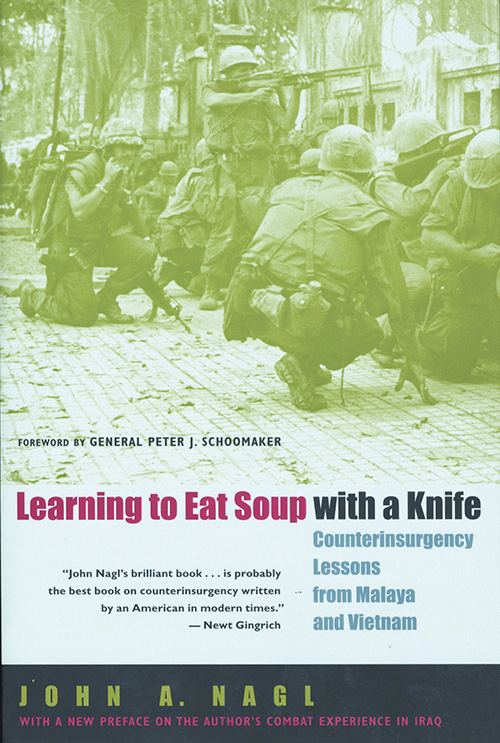

University of Chicago Press

Bottom Line up Front – A Counterinsurgency Army and a Conventional Army Are Different

The fact that it takes an army a long time to switch within the Spectrum of Conflict is broadly agreed upon. Soldier and distinguished academic Dr. John A. Nagl discusses the organizational cultural differences in his book, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife. He believes that conventional and unconventional warfare are so different that, “…to succeed in one [it] will have great difficulty in fighting the other.”4 The two armies have fundamentally- different organizational cultures that prioritize and mitigate different aspects of their organization. As Robert M. Cassidy, who holds a doctorate in strategy and irregular warfare, and teaches at Wesleyan University, stated in Back to the Street without Joy: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Vietnam and other Small Wars, the goal would be to “…not fight small wars with big-war methods.”5 The two armies have different attitudes and assumptions around the application of combat. These assumptions are not complementary in either theatre.

In the early-2000s, while the Iraqi insurgency was escalating, the US Army questioned the effectiveness of its culture and attitudes in relevant operations. General David H. Petraeus wrote his manual on Counterinsurgency in 2006. He describes the conventional army’s inclination to wage war on insurgents, and argues that armies need to overcome that inclination in order to be successful.6 There is an assumption that a conventional army will use offensive action and aggressively fight insurgents. This culture has been built out of an assumption that ‘taking the fight to the enemy’ is the only way to turn the tide on a counterinsurgency. General Petraeus uses examples from the last century, and makes the case that conventional armies tend to centralize decision making and apply too much force in a counterinsurgency. He argued in his manual that one cannot simply overwhelm the enemy with combat power. Rather, one needs to focus upon the local population. Brigadier Nigel Aylwin-Foster of the British Army reflected upon the coalition campaign in Iraq after 2003 and opined that although the US Army was “…indisputably the master of conventional warfighting,” it was less proficient at the counterinsurgency they were waging.7 He supported General Petraeus’ argument that the organizational culture of the conventionally focused American Army was not suited to fighting a counterinsurgency.

DND photo AR2010-0177-01 by Sergeant Daren Kraus

General David Petraeus (left), Commander International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), and General Jon Vance, Commander Task Force Kandahar (TFK), survey/tour a newly-constructed checkpoint, 9 July 2010.

Culture for the Canadian Conventional Army

Since the Second World War, Canada’s foreign policy has been that of “protection and projection.”8 Canada has championed a non-interventionist strategy that respects the equality of states and state sovereignty. In the Cold War, Canada sought self-preservation and national protection. Those goals guided Canada towards participation in the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Canada tended to mitigate political tensions that “Ottawa feared would spark a Third World War.”9 This ability to mediate the tensions between the most powerful states was not as important after the Cold War. After the Cold War, the Canadian Armed Forces have instead projected their power in order to gain influence.

In the 1990s, the Canadian government expected its army to operate across the Spectrum of Conflict. In 1994, Canada’s training manual, Training Canada’s Army, (see Figure 1) wanted the army to be prepared for all conflicts, from high-intensity missions – to low-intensity missions.

The manual, Training Canada’s Army, contends that although Canada is frequently involved in conflict represented by View 2, it still has a standing requirement to be prepared for the higher intensity conflict represented by View 1. This document maintains that the effectiveness to engage in View 2 rests upon one’s ability to demonstrate combat power in View 1. By the late-2000s, particularly after Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan, the army recognized that it could not train for all Spectrums of Conflict. Instead, it needed to master a specific or niche area. By the early-2010s, the Canadian Army was focussing upon conventional Brigade operations, and in particular, the Brigade Fixed Defensive, Brigade Attack, Deliberate River Crossing and Mobile Defence. Canada has thus shaped its army on its competency to fight as a Brigade in a high-intensity conflict.

As described in Figure 2, the Canadian Army has a three-year training cycle wherein each of the three Brigades cycle through the following three phases: Support/Reconstitution, Training, and Operations. The Canadian Brigades train up to the Formation Level in a Divisional Context wherein the high readiness Brigade conducts a cumulative two-week exercise to test the Brigade against a live enemy force. The level of training ensures that the Brigade Headquarters can conduct live brigade group operations, including deep targeting, joint, and combined missions.

The Canadian Defence Policy, Strong, Secure, Engaged (2017), discusses the mandate to train at the Brigade Group level. It is recognized as the minimum level in order to prosecute joint campaigns where one can integrate other departments, non-governmental organizations and coalition partners. These Brigade Groups must be able to provide “high-end war-fighting skills.”12 The Defence Policy believes that a well-trained combat force can rapidly adapt to the lower-end operations, if required to do so.

The behaviours of the Canadian Conventional Army are as follows:

- The Canadian Army Commands and Controls the mission and provides top-down direction in order to fight the enemy. The military culture is one of centralized command that provides overarching guidance;13

- The Canadian Army will focus upon finding and destroying the enemy. It tends to conduct missions to break the enemy’s decision cycle and initiative;14 and

- The Canadian Army has a pre-disposition to offensive operations and the focus is upon confronting issues head-on.15

Canada’s military expects Command and Control from its leaders. Other organizations are more prepared to collaborate and cooperate. The military makes ‘decisions,’ while other organizations make ‘recommendations.’16 The assumption of the Canadian Army is that an aggressive offensive attitude that takes the fight to the enemy is paramount. It believes that it must find and destroy the enemy to win the battle. The culture is formed from these assumptions.

Culture for Fighting a Counterinsurgency

It would be difficult to outline the perfect culture for a counterinsurgency force in a few paragraphs. Therefore, I will outline what I believe does not work, and use those beliefs as the basis for formulating guiding principles. Western militaries – ones that are governed by elected civilians – are expected to win wars in a swift and violent way.17 The army is simply a reflection of civil society. The civil society wants quick results and does not want to be engaged in a prolonged situation. When countries such as Canada deploy forces to fight in counterinsurgencies, they tend to conduct operations that seek to ‘hunt down the insurgents.’ However, a counterinsurgency force needs long-term solutions focused upon the local population.

The predisposition to conduct offensive operations is not just exemplified by the Canadian Army experience when it fought in Kandahar, Afghanistan. It was also an issue with the American military in Iraq. Of the 127 pacification operations the American Army conducted in Iraq between May 2003 and May 2005, most were launched to find, fix, and strike insurgents. Only 6 percent of the operations were directed in supporting the local government.18 Patrolling often is focused upon a military objective and less upon interacting with the local people. A counterinsurgency force must assume that the people are the most important focal point of the conflict and consideration of them must be at the foundation or core of all operations.

The behaviours required of a counterinsurgency force are as follows:

- Develop sound administration in the local area in order to meet the local requirements.19 Focus upon the social, economic and political developmental need of the people with an integration of civilian activities. They must Coordinate and Cooperate with all stakeholders in the conflict. As discussed in the Counterinsurgency manual, it is about meeting “the local populace’s fundamental needs;”20

- (As General McCrystal, Commander of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2010 stated, the strategy would be “…protection of the Afghan population over the killing of insurgents.”)21 [The military must] operate with the lowest application of force and minimum loss of civilian life;22 and

- Develop the indigenous troops and deploy as many as practicable. Empower the local people to restore law and order.23

The counterinsurgency force must assume that the local population is the most important aspect of the operation. All use of force, operations, and development must be focused upon building a stronger relationship with the local population. The counterinsurgency force must act as the overarching ‘police force’ that protects the population and develops the indigenous troops.

DVIDS/Photo ID 266517

General Stanley McChrystal during a field visit in Afghanistan, 30 March 2010.

Conclusion

The culture of a Conventional Army is one of command and control, and of aggressive operations to destroy the enemy. The culture of a successful counterinsurgency force is one of coordination and collaboration, focusing upon protecting the population and developing the indigenous troops. These cultures are formed by the assumptions generated with respect to how they will win the conflict. Although both armies operate in a hostile environment, they are ‘playing very different sports.’ As expressed within the analogy, the cultures affect the way each team structures their meetings, makes decisions, runs training, improves the team and interacts with the stakeholders. The culture of the two armies requires years to change.

The Canadian Army, as with most Western armies, is expected to fight along the entire Spectrum of Conflict. This article has hopefully provided a quick study of why an army cannot simply change its equipment and rules of engagement – and expect success along the entire Spectrum of Conflict. Instead, it requires a different army. The Canadian Army has chosen to be proficient at the higher level of conflict in order to reduce the risk in the next major conflict. To be truly successful in a counterinsurgency, one needs to change the culture and assumptions. NFL teams are horrible at Rugby – and Rugby teams are horrible at Football. We must understand that there is a fundamental cultural difference between these different armies if we are going to prepare for different conflicts.

Major Caleb Walker has a Master’s degree in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, is a graduate of the Canadian Army Technical Staff Course, the New Zealand Command and Staff Course, and has completed a Masters in International Security from New Zealand. A veteran of three tours in Afghanistan, for which he received a CDS Commendation, he is currently assigned to Canadian Army Headquarters as the Canadian Army Tracker.

Notes

- “Edgar Schein Model of Organization Culture,” Management Study Guide, dated 19 November 2017, at: http://www.managementstudyguide.com/edgar-schein-model.htm

- E. H. Schein, “Organizational Culture and Leadership Defined,” In Organizational Culture and Leadership. (San Fransisco: Jossey Bass, 2010), p. 8.

- Ibid, p. 11.

- John A. Nagl, “Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife,” in World Affairs, Vol. 161, No. 4, p. 196.

- Robert M. Cassidy, “Back to the Street without Joy: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Vietnam and Other Small Wars,” in PARAMETERS, (Summer 2004), p. 80.

- General David Petraeus, Field Manual 3-24 Counterinsurgency. (Washington: Department of the Army, 2006), p. ix.

- Brigadier Nigel Aylwin-Foster, “Changing the Army for Counterinsurgency Operations,” in Military Review, (November-December 2005), pp. 2-3.

- Robert W. Murray and John McCoy, “From Middle Power to Peacebuilder: The Use of the Canadian Forces in Modern Canadian Foreign Policy,” in American Review of Canadian Studies, Volume 40, 2010 – Issue 2, p. 173.

- Ibid, p. 175.

- “Chapter 2 Training and Operations,” Training Canada’s Army, dated 19 November 2017, p. 14, at: http://armyapp.forces.gc.ca/olc/Courseware/AJOSQ/JTRG/jtrg_01_02/references/

JTRG_01.02_B-GL-300-008_E.pdf. - Ibid, p. 18.

- Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, “Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy,” 2017, p. 36.

- Aylwin-Foster, p. 7.

- General David Petraeus, Field Manual 3-24 Counterinsurgency, p. 5-2.

- Aylwin-Foster, p. 3.

- Adrienne Turnbull and Patrick Ulrich, “Canadian Military-Civilian Relationships within Kandahar Province,” NATO STO-MP-HFM-204, p. 5-3.

- Nagl, p. 9.

- Aylwin-Foster, p. 5.

- Nagl, p. 195.

- Petraeus, p. 2-1.

- Murray and McCoy, p. 171.

- Cassidy, p. 80.

- Ibid.

DND photo ISX02-2018-0001-002 by Corporal Kyle Van Tol DND photo IS03-2018-0043-003 by Master Corporal Jennifer Kusche

Members of Operation Presence – Mali Force Protection discuss the plan to provide security in Gao, Mali, 17 July 2018.