Command and Responsibility

DND photo XA01-2019-0035-905

Military Commanders’ Responsibility for Members’ Health

by Marc Bilodeau

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Brigadier-General Marc Bilodeau is a Medical Officer who currently serves as the Canadian Armed Forces’ Deputy Surgeon General. He graduated from Université Laval in 1998 with a Doctorate in Medicine, and from RMC in 2019 with a Master of Public Administration. This manuscript is inspired by an academic paper submitted on 27 May 2019 as a required assignment for the Canadian Forces College’s National Security Programme. The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Richard Goette, Dr. Robert Engen, Colonel Dave Abboud, Commander Rob Briggs, and Major-General (ret’d) Daniel Gosselin for their generous contributions in reviewing this manuscript and providing meaningful suggestions with respect to its content.

Introduction

The recent Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) refocus upon people highlights the importance of human resources as the most crucial asset of a military organization. Yet, more than a thousand well-trained CAF Regular Force members are released from the military in any given year, many of them due to preventable illnesses or injuries. We have more opportunities than we are taking advantage of to optimize the health and resiliency of CAF members and preserve this precious asset. The health and wellness of CAF members is a shared responsibility between the member, the Canadian Forces Health Services Group (CF H Svcs Gp), and the military chain of command (CoC). The CoC is the most critical part of the health and wellness equation.

Leadership, beginning at the highest levels of the organization, is a vital force in influencing the health of CAF members. This article addresses the following questions: Are CAF military commanders given the appropriate tools to effectively achieve their responsibility for improving the health of their members? If not, how can the organization better support its leaders?

The article argues that the health and the operational readiness of CAF members could be enhanced if the CoC would be enabled with the appropriate tools to do so. It will first describe the concepts of individual health and institutional military readiness, exposing how both concepts are inexorably linked to each other. The shared responsibilities of the individual, the CF H Svcs Gp, and the CoC for health in the CAF will then be presented. Using the institutional analysis model,1 I will then establish the institutional gaps in the existing CAF health governance structure that could explain the sub-optimal health trends within the CAF. Finally, I will propose a realistic and comprehensive way ahead that could reverse those trends, and improve the overall health and operational readiness of the CAF.

Health and Readiness

Defining health and readiness will expose the linkages between the two concepts while explaining their importance in CAF’s recent increased focus on its people.

Defining Health

As per the World Health Organization (WHO) constitution, health is defined as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”2 The WHO considers health as a fundamental human right, and its constitution highlights governments’ responsibility for the health of their people. The 1986 Ottawa Charter re-emphasized the importance of social well-being as a component of health, stating that to be healthy, “…an individual or group must be able to identify and to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or cope with the environment.”3

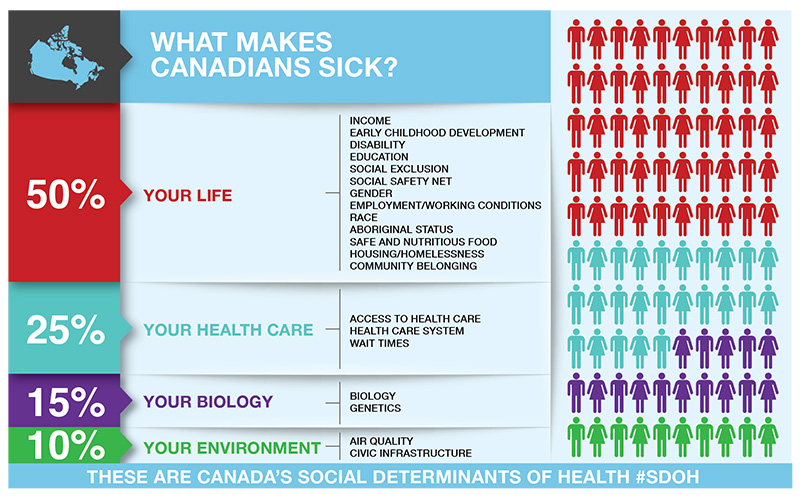

In addition to genetics and social habits, health is also influenced by the social determinants of health. These determinants have been adopted by the Public Health Agency of Canada, and are illustrated in Figure 1.4 The concept of total health, described as “a dynamic state of wellbeing characterized by a physical, mental and social potential,”5 has also emerged over the last decades. In the Canadian military context, health goes beyond the period of service, and it is approached from a lifelong perspective.6

Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm: Institute for Futures Studies.

Figure 1: The Main Determinants of Health7

The concept of resilience has also gained traction lately. It is defined as “the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties.”8 Resilience is closely linked to fitness, which itself is defined as “a state of adaptation in balance with the conditions at hand.”9 These two concepts are influenced by many domains: medical, nutritional, environmental, physical, social, spiritual, behavioural, and psychological, and are interdependent with the notion of health.10 Someone can be fit to achieve a task but still be unhealthy, which could negatively impact their resilience. Conversely, a disability for which an individual has been compensated does not mean that this person is unhealthy or even unfit; many amputees are fully functional and highly resilient.

Defining Readiness

In a military setting, collective readiness means having “…enough of the right types of skilled and adequately trained personnel, and […] adequate stocks of equipment in good working order.”11 This definition does not, however, capture the qualitative component of individual readiness. A more useful definition incorporating this component would be: “a combination of a soldier’s willingness and ability to do his job and cope in peacetime and during combat.”12

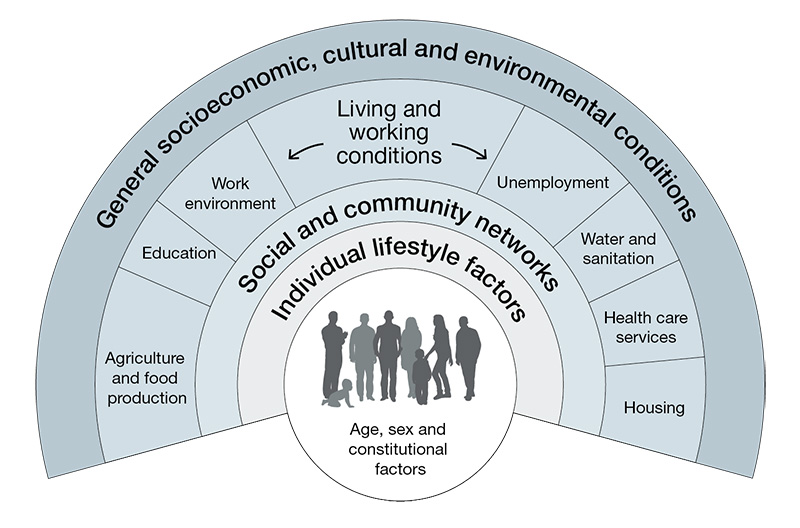

The United States Military Health System was first to adopt a framework, called the Quadruple Aim that identifies population health as a critical component of medical readiness. This concept is defined as “ensuring that the total military force is medically ready to deploy.”13 The CF H Svcs Gp has recently adapted the Quadruple Aim framework, conveying readiness as Operational Excellence (Figure 2).

Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy – 2017 Integration for Better Health, National Defence, p. 14

Figure 2: CF H Svcs Gp’s Quadruple Aim.14

Linking Health to Military Readiness

Based upon the definitions of health, resilience and fitness proposed above and the introduction of the Quadruple Aim framework, one can draw obvious parallels between these concepts and military readiness. As stated by Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation specialist Dr. Gregory D. Powell, “combat readiness and levels of fitness are intimately related.”15 It can be argued that the social determinants of health, as much as the resiliency and fitness domains, are also factors of readiness.

There is historical evidence that readiness is negatively impacted by sub-optimal health. Observations from recent conflicts indicate that about 80% of hospital admissions are the consequence of disease and non-battle injuries, many of them preventable.16 Therefore, the better the total health of its serving members, the higher the readiness of a military organization. The healthier the soldiers of a nation are, the more likely its military will have a competitive advantage over an adversary.

Furthermore, the cost of poor health cannot be ignored. For example, obesity, which is associated with personal life habits, is a predisposing condition for many diseases, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and osteoarthritis. An individual’s medical readiness is not the only aspect impacted by obesity. The costs associated with treating obesity, and the medical consequences of this condition, have a significant financial impact upon the CAF, preventing the organization from using these funds somewhere else, thus, indirectly impacting readiness.17 There is also evidence, according to a study done by Dr. Anthony Tvaryanas, an American aerospace medicine specialist, that “…the cost of lost productivity secondary to health-related conditions (presenteeism) exceeds the costs of direct medical care.”18 In addition to absenteeism, this notion is not insignificant for such issues as mental illnesses.

Responsibility for Health

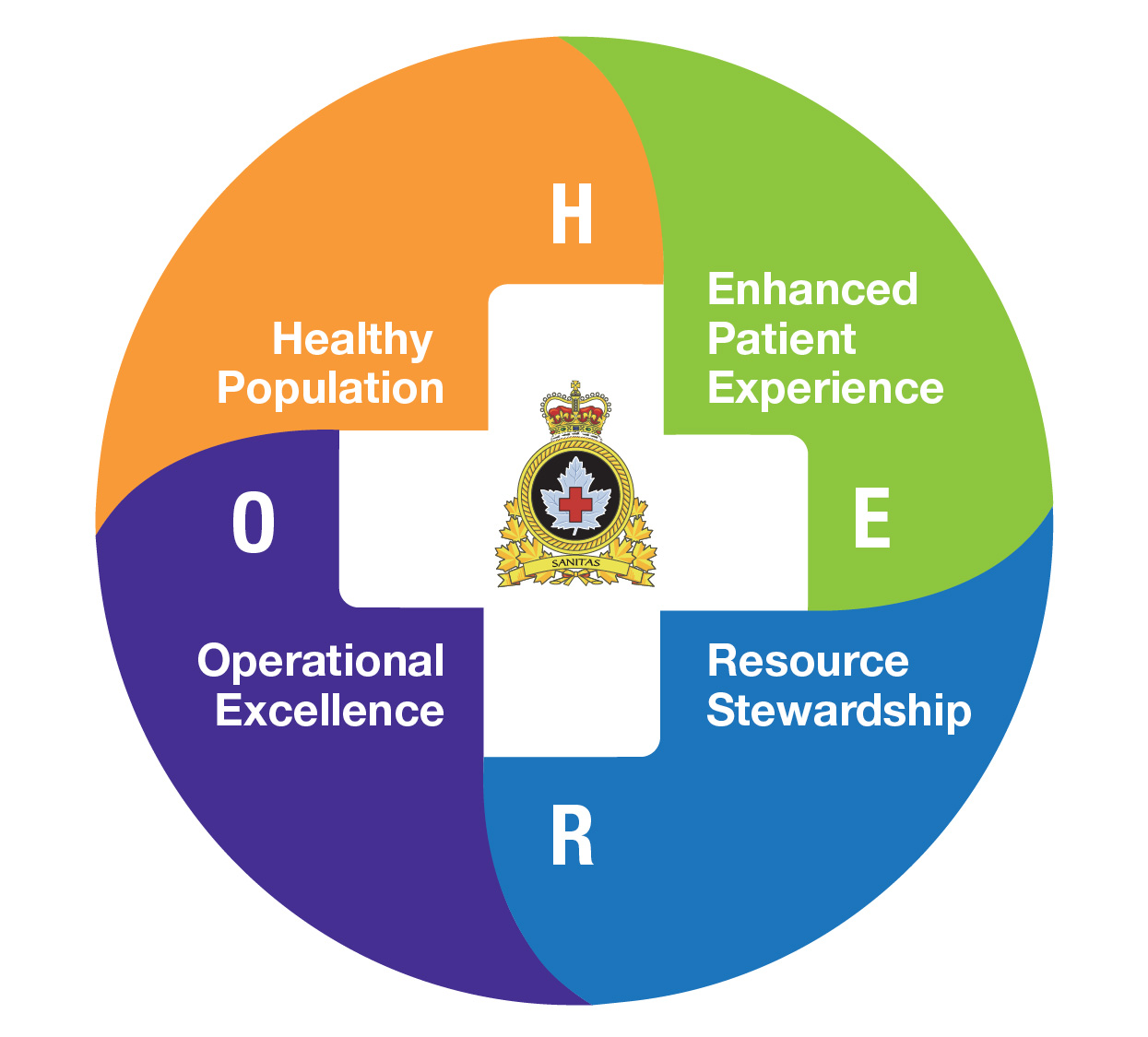

Health is a complex notion influenced by many interrelated domains. Such a level of complexity justifies a partnership to obtain better health results. The importance of integration and partnership to improve health has long been recognized within the CAF. This integration is captured in the Triad of Responsibility, illustrated in Figure 3. This section will describe the role played by each of these stakeholders to achieve better health.

Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy – 2017 Integration for Better Health, National Defence, p. 11

Figure 3: Triad of Responsibility.19

Individual Responsibility

As described in the Surgeon General Integrated Health Strategy, “CAF members and their families must be fully engaged as a partner in their health, […] so that they can improve their quality of life, long-term wellbeing and resilience, as well as their operational readiness.”20 Member engagement is critical in achieving better health, and this is independent of the health services offered by the CAF. The military code of conduct as described in Duty with Honour expects each CAF member “…to be held accountable for his or her performance, always acting in compliance with the law and maintaining the highest standards with respect to all the professional attributes.”21 One of these attributes is physical fitness.22 The expectation towards greater engagement of members is also part of a novel health care approach associated with better health outcomes that the CF H Svcs Gp has adopted under its Patient-Partnered Care Framework.23

Health Services Group Responsibility

The role of the CF H Svcs Gp in improving health is challenging for many reasons. First, the Canada Health Act excludes CAF members from the provincial responsibility to provide health services to their citizens, creating the requirement for the CAF to build its own health care system.24 The National Defence Act itself is, however, silent regarding health care.25

The CF H Svcs Gp is, therefore, de facto, mandated to provide health services, including deployable capabilities in support of CAF operations.26 Its mandate is similar to the Canadian provinces and territories’ responsibility to provide care to their citizens. Based upon Canadian Medical Association statistics, the lack of access to health services represents only 25% of what makes Canadians sick (Figure 4). There are several other ways to improve health that do not involve the provision of health care at all.

Secondly, instead of being a reactive system which provides acute or episodic care to ill and injured personnel, the CF H Svcs Gp has favoured programs which prevent illness and injuries and promote healthy lifestyles.28 Strengthening the Forces (StF) is a voluntary health promotion program delivered on CAF bases and wings, focusing upon addiction, injury prevention, inactivity, and social wellness.29 This program is aligned with the principle that preventive health care is significantly more efficient than curative health care.

Finally, the CAF has a legal obligation under the Canada Labour Code (CLC) and the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations “…to ensure that the health and safety at work of every person employed by the employer is [sic] protected.”30 CAF leaders who exercise authority for their members are responsible and accountable for the implementation and enforcement of the CAF General Safety Standards.31 Chapter 34 of the Queen’s Regulations and Orders (QR&O) states that “…the senior medical officer at all levels of command is the responsible adviser [sic] to the senior officer exercising the function of command or executive authority on all matters pertaining to the health and physical efficiency of all personnel under his jurisdiction.”32 By extension, the Surgeon General, the top CAF physician, is, therefore, the health advisor to the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS). The QR&O also explicitly state that “…a commanding officer is responsible for the whole of the organization and the safety of the commanding officer’s base, unit or element.”33 The CF H Svcs Gp supports CAF leadership in meeting these critical Force Health Protection functions, as a sub-component of Force Protection which is “essential to operations—and, therefore, a clear responsibility of command.”34

Command Responsibility

In his Guidance to Commanding Officers (CO) and their Leadership Teams, the CDS expressed: “The CAF must be fit to fight. COs and their leadership teams are responsible for the promotion of health and fitness within their units.”35 He also expects his leadership teams to be “…working closely with our medical professionals to develop and maintain the climate of trust and understanding required to support healthy lifestyles.”36 Command responsibility is central to ensuring fitness to fight, which depends highly upon health and fitness.

The Guidance’s chapter on physical fitness explains that “…it is about cultivating and promoting a culture that values health and wellness, and recognizes how this contributes to operational readiness, resilience and the long-term health of our personnel and their families.”37 It similarly addresses the mental health aspect of command responsibility.38 Finally, the document highlights the importance of creating a climate of trust and confidence in facilitating access to health services.

The leadership team’s obligation regarding members’ health is also mentioned in several other doctrinal documents. The QR&O define a specific role for the non-commissioned members in promoting “…the welfare, efficiency and good discipline of all who are subordinate to the member.”39 Duty with Honour assigns to the profession of arms the responsibility to “…ensure the care and well-being of subordinates.”40 The Conceptual Foundations of Leadership in the Canadian Forces identifies member well-being and commitment as one of three value dimensions critical to effectiveness and mission success.41 This notion is expanded further in Leading the Institution by calling for a transformation to a culture of understanding where “…leaders emphasize proactive influence behaviours such as facilitation, support, participation and delegation.”42 instead of a culture of rules-based compliance. The latter also links members’ quality of life with optimal performance.43 Centuries of lessons learned have also shown that the conditions of the workplace are more important in motivating soldiers than many human resources programs. Dr. Alan Okros, a professor at the Canadian Forces College, states that loyalty and obligations to their peers are inspiring factors for employees, hence the importance of “…behavioural influences from leadership, institutional culture and team climate” to achieve sustained commitment.44

According to the CAF, “…honouring the social contract is essential to maintaining legitimacy in the eyes of the public,” articulating the moral responsibility that CAF members have towards Canadians.45 This societal framework between Canadians and their military stems from the CAF members’ willingness to put the needs of Canada and Canadians before their own. In turn, CAF members expect to be given appropriate benefits and support for themselves and their families. As the doctrine states, “This social contract is an unbreakable common bond of identity, loyalty and responsibility which has sustained the military forces of Canada throughout their already significant involvements on the world stage.”46

There is, however, a tension between mission requirements and the well-being of members.47 This tension, defined as the concept of unlimited liability, will sometimes force commanders to place their subordinates in harm’s way, therefore putting their health at risk. It also drives the constant requirement of military leaders to “…balance mission accomplishment with members’ well-being.”48 The primacy of operational effectiveness and mission accomplishment assigned by the Canadian government cannot be ignored, and, according to the CDS, “…is the fundamental criterion against which all personnel functions and supporting policies must be developed and evaluated.”49 It requires the delicate balancing of the individuals’ needs against the collective needs. This tension was reaffirmed when the CDS launched Operation Honour in 2015, declaring “People First, Mission Always.” This focus upon people was also confirmed in our Canadian defence policy, Strong, Secure, Engaged (SSE), with its first chapter dedicated to people.50

Finally, the approach of making the COs and their teams responsible for the health of their members is not unique to the CAF, as shown in the NATO Field Hygiene and Sanitation standards that make unit commanders “…responsible for all aspects of health and sanitation.”51 Most contemporary military organizations proclaim a similar intent. While an essential component of command, this responsibility aspect of the Defence Scientists’ Ross Pigeau and Carol McCann Competency, Authority, and Responsibility (CAR) model seems insufficient to make commanders effective in achieving the desired outcomes.52

DND photo XA01-2019-0035-886, by Corporal Stuart Evans

Improving Health to Enhance Readiness

Despite the conditions being in place to ensure optimal health and fitness levels for our members, the current health status of the CAF, and its trends over the last few decades are not encouraging. They will now be discussed.

Current CAF Health Status and Trends

The most recent Health and Lifestyle Information Survey (HLIS)53 revealed that the overall perceived health status, health-related activity limitations, chronic conditions, and rate of acute injuries have not changed compared to previous surveys.54

Members still spend a significant amount of time away from work. Indeed, 18.4% of Regular Force members had missed a minimum of a day of work as a result of illness or disability in the month before the questionnaire was answered. This number translates to about eight workdays per year, which is slightly above the Canadian population average of 7.7 days.55

Stigmas related to mental health issues, while significantly reduced, still exist. Only 60% of personnel who contemplated suicide in the previous 12 months sought mental health support, and only 50.9% of those knew where to find help after hours. As well, about 20% of CAF members are still engaged in high risk or harmful drinking activities.56

The survey further demonstrated an increase in repetitive strain injuries from 22.6% to about one-third. Two-thirds of members have engaged in unsafe physical training practices, resulting in an injury for 12.5% of them. Obesity and overweight rates (25% and 49% respectively) have also increased among CAF personnel in the last decade. The smoking rate is otherwise steadily decreasing, but 18.5% of current smokers started smoking after joining the CAF, 57.1% of them during basic training.57

There seems to be a better awareness of Strengthening the Forces programs, mainly for the 40 to 60-year-old group. The 18 to 29-year-old group does not appear to be adopting healthy lifestyle changes. The number of hours spent on sedentary activities increased by more than three hours since the previous survey, and six hours from the one before that. Finally, only 28.7% of personnel consumed more than six servings of vegetables and fruits per day, and more than half underestimated Canada’s Food Guide recommendations for this food group.58 These negative trends need to be analyzed to understand the underlying reasons for them in order to develop potential solutions.

Gap Analysis

Using American sociologist Dr. Richard Scott’s institutional analysis model, a gap analysis was conducted to understand the reasons for the sub-optimal health trends of the CAF population.59

Scott’s regulative pillar refers to institutions’ ability to establish rules, monitor conformity, and use sanctions and rewards to influence behaviour compliance.60 Most CAF rules are clear, such as what is stated under the Universality of Service principles, stipulating that every member must “be physically fit, employable and deployable.”61 A clearly-defined process also exists to describe the consequences of a failure to achieve the Physical Fitness Standards when it is determined to be within the member’s control. Such failure, when recurrent, could ultimately result in a release from the CAF.62

There is a requirement for a member to be assessed by a CAF health care provider whenever there are indications of a health problem on the screening questionnaire conducted before a fitness test. This evaluation could subsequently result in the assignment of Medical Employment Limitations, which may preclude the member from attempting the test. It could also, ultimately, result in a medical release from the CAF. A more extensive suite of benefits accompanies this type of release, compared to non-medical releases. This phenomenon could be a partial explanation of the proportion of members being released for medical reasons, and the difficulty in returning members to work after an illness or injury.63 Finally, while medical and physical fitness is monitored individually for each member and reported to their commanding officer, there is currently no easy way to track the fitness level from a unit, formation, or service perspective. The HLIS is the only tool available that provides a snapshot every four-to-five years, which informs CAF leaders.64

There is a pressing need for military leaders to have better and timelier access to information about the health status of their members at the population level. Also, there may be too many incentives to remain sick or disabled, in comparison to staying healthy or recovering actively from an illness or injury. U.S. Army General William Westmoreland stated in 1963: “…the effective platoon leader (1) clearly and consistently emphasized performance as the basis of reward and punishment; (2) used punishment instructively and for motivational failure and (3) communicated clearly about the standards he desired.”65 The absence of health information does not allow for the development of evidence-informed policy to adequately influence health-related behaviours. The CAF narrative would also benefit from a more positive approach to health and wellness.

The normative pillar, based upon societal values and norms, refers to the roles given by society to people, and expected behaviours devolved from such responsibility.66 The military mandate, duties and privileges relate to the social contract associated with the profession of arms described earlier. It also speaks to the CAF ethos of “duty, loyalty, integrity, and courage.”67 The concept of duty relates to the performance expected from members, which is closely associated with courage, which requires both physical and moral capacity. The notion of integrity refers to the obligations towards responsibility and being held responsible, while loyalty, is directed both towards the CoC and peers.68 The current version of Duty with Honour is ten years old. Younger CAF members do not seem as responsive to the recommendations to adopt healthier lifestyles as older members. Is this an indication that these generations do not connect with the way the military ethos is presented to them? It might be worth re-assessing the resonance of the military ethos in the context of today’s society. Its modernization might be required to reinforce these essential principles. This review could incorporate gender and diversity concepts in the post-Operation Honour era. It could underscore the importance of leadership in reducing stigma, as shown within the mental health domain. It could also expand further upon the crucial role of the NCMs as transformational leaders.69 The next edition of Duty with Honour is in development.70 This review would be an excellent opportunity to incorporate the value of health and fitness, ensuring it is being reinforced as a critical component of our military identity.

Finally, the cultural-cognitive pillar refers to the cultural systems that drive shared understanding and ideologies, creating collective meaning that results in actions. This pillar is attached to a strong emotional reaction: “Actors who align themselves with prevailing cultural beliefs are likely to feel competent and connected; those who are at odds are regarded as, at best, clueless or, at worst, crazy.”71 In the military context, this pillar is powerful for influencing behaviours. The significant reduction of smoking in the military could be explained by the successful information campaigns related to the risk of smoking, combined with peer pressure resulting from smoking being no longer considered culturally acceptable.

The CAF, therefore, needs to capitalize upon the power of culture in creating peer pressure to influence behaviours. Inter-unit competitions need not be only related to elite performance, but can be applied to simple health habits related to physical activity, diet, stress management, smoking, and sleep. These would be instrumental in creating that new culture of health and fitness that would ultimately enhance the military organization. It might also be worth considering changing the lens through which the organization looks at health issues.

Consideration should be given to switching from a paternalistic, disease-centric, acute care model, to a partnership model, focusing upon prevention and health optimization. This new perspective would replace the emphasis upon sickness, with a focus upon wellness.

Scott’s model allows for a detailed assessment of the potential gaps in optimizing health in support of military readiness. The proposed tools, summarized in Table 1, could if implemented, offer a stronger alignment of the CAF institutional pillars, ultimately leading to better health outcomes. These tools would provide commanders with the authority component of the Competency, Authority and Responsibility (CAR) model to positively impact the health of their members, using their position of influence and assuming their assigned responsibility for health.72

| Regulative pillar | Normative pillar | Cultural-cognitive pillar | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently in place |

|

|

|

| What’s missing |

|

|

|

Author

Table 1: Gap Analysis using Scott’s Model.

A Proposed Way Forward

Based upon previous successes, such as reducing the stigmas related to mental health issues or reducing smoking rates, the evidence available fully supports the possibility of behavioural change. Top leadership involvement and buy-in are critical to success; without them, no meaningful change is possible. Fortunately, CAF leadership buy-in should not be problematic. A few notable examples are the Canadian Army Integrated Performance Strategy, launched in 2015,73 and the Royal Canadian Navy Health and Wellness Strategy, implemented around 2012, which have led to significant improvements.74 Other promising improvements came with the release, on January 2017, of a strategic initiating directive by the CDS and the Deputy Minister of National Defence on total health and wellness.75 This direction was subsequently reinforced in Strong, Secure, and Engaged,’ wherein $198.2 million was promised to “favour a more comprehensive approach to care—known as ‘Total Health and Wellness’—which will consider psychosocial well-being in the workplace, the physical environment, and the personal health of members.”76 It will also “support health and resilience; promote a culture of healthy behaviour; and support military families.”77 A strategic framework is currently being developed; the most recent draft consulted addresses the crucial role of leadership in such an endeavour.78 The framework will ultimately lead to the release of a strategy and action plan.79

Finally, BALANCE, the CAF Physical Performance Strategy was recently published, and it focuses upon critical elements, such as “…be trained and fit, properly fueled, well-rested, and free from injury” that drive performance and operational readiness.80 Physical activity, nutrition, sleep and injury prevention constitute the Performance 4 (P4) behaviours as the foundation of this strategy. It recognizes the importance of building a culture of fitness within appropriate policy, social and physical environments to support it.81 As well, it highlights the shared accountability between the institution, its leaders and its individuals for achieving the desired outcomes.82 Finally, it relies upon a decentralized execution by allowing each Level 1 command to provide their own implementing directions, thus enabling a more targeted approach to various sub-groups of the CAF.83

The alignment of these initiatives creates a clear and explicit common intent, which is “key to co-ordinated military action,” as proposed by Pigeau and McCann.84 The current conditions seem optimal to fill the gaps identified above by providing the CoC with the tools they require for success. Historically a topic rarely written about by military leaders, health is now becoming a key message with the potential to “…have a significant impact on the attitudes and behaviors of military personnel.”85 BALANCE also provides a measurement framework that could monitor the total health and offer a transparent dashboard for all levels of command. This tool could be modelled on the US Army Medical Readiness Assessment Tool.86 There is also a need to capitalize further upon positive incentives, such as the FORCE Rewards program, to remain fit or to recover from an illness or injury.87 The culture change that could result from such initiatives in targeting healthy behaviours has the potential to become one of the most significant outcomes of this re-alignment. It might also result in the re-framing of the narrative from disease and sickness to health and wellness. A strong commander’s voice, such as the one expressed by General Westmoreland, is an essential aspect of stigma-reducing efforts.88 The current refresh of the military ethos documentation to better align with younger generations will also be beneficial in capitalizing upon the changes described herein.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, sustained leadership commitment and role modelling are crucial to affect change. This component feeds into the competency domain of the CAR model.89 As stated by a United States Army Medical Corps colonel in 1951: “The greatest responsibilities of the commander is that once having initiated an action designed to maintain the health of his men, he himself must always be the shining example of compliance with that action. […] The personal responsibility and self-discipline displayed by a commander in health measures cannot be overestimated because, if he himself fails, so will the measures.”90 This quote reinforces the importance of role modelling and testimonials by senior military personnel sharing their own story of health struggles to further reduce stigma.

Conclusion

The recent CAF focus upon people has led to the release of several closely aligned strategic documents aimed at improving the health of the CAF population, and thus, CAF operational readiness. This re-alignment creates the ideal conditions to undertake coordinated actions. While health is a shared responsibility between members, the CF H Svcs Gp and the CoC, CAF leadership is the critical component of this equation.

This article has attempted to demonstrate that military commanders are currently not being provided with all the tools they need to influence the health of their members. It also argued that they would be in a stronger position to affect the overall health status of the CAF, and ultimately, its operational readiness if they were provided additional tools. Improving the collective CAF health requires a robust measurement framework that would allow real-time monitoring of population health status. It also calls for a cultural change towards health and wellness in contrast to disease and sickness, and the appropriate incentives to support such an approach. The refresh of our military ethos could better communicate its relevance for younger generations.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a strong and sustained leadership commitment will be the critical enabler in balancing the command envelope required for any effective command-driven change.91 The voices and actions of commanders need to be heard and felt to maintain the momentum established by the recent strategic documents. These actions will result in healthier behaviours and enhanced operational readiness for the CAF.

DND photo KW06-2017-0067-015

Notes

- W. Richard Scott, Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, 4th Edition, (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2014).

- World Health Organization, “Constitution,” accessed 3 May 2019 at: <https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution>.

- World Health Organization, “WHO | The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion,” accessed 3 May 2019, at: <http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/>

- Public Health Agency of Canada, “Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequalities,” 25 November 2001.

- Johannes Bircher, “Towards a Dynamic Definition of Health and Disease,” in Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, Vol. 8, No. 3 (November 2005), p. 335.

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group, “Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy,” (National Defence, 2017), p. 2.

- Dahlgren G., Whitehead M. (1991). Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies.

- Oxford Dictionaries, “Definition of Resilience,” Oxford Dictionaries | English, accessed 3 May 2019, at:<https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/resilience.>

- Michael Mullen, “On Total Force Fitness in War and Peace,” in Military Medicine, Vol. 175, No. 8:1 (2010), p. 1.

- Sean Robson, Psychological Fitness and Resilience: A Review of Relevant Constructs, Measures, and Links to Well-Being, RAND Project Air Force Series on Resiliency (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2014), p. iv.

- Jason Forrester, Michael O’Hanlon, and Micah Zenko, “Measuring U.S. Military Readiness,” in National Security Studies Quarterly VII, No. 2 (Spring 2001), pp. 99–100.

- Robert J. Schneider and James A. Martin, “Military Families and Combat Readiness,” in Military Psychiatry Preparing in Peace for War, Chapter 2, 1994, p. 20.

- Military Health System, MHS Quadruple Aim (United States, 2013), at: <https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Glossary-Terms/2013/04/09/MHS-Quadruple-Aim.>

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group, Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy – 2017 Integration for Better Health, National Defence, p. 14.

- Gregory D. Powell, Daniel Dumitru, and Jeffery J. Kennedy, “The Effect of Command Emphasis and Monthly Physical Training on Army Physical Fitness Scores in a National Guard Unit,” in Military Medicine, Vol. 158, No. 5 (1 May 1993), p. 296.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Field Hygiene and Sanitation,” Standards Related Document (NATO Standardization Office, July 2018), pp. 1-1,1-2.

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group, “Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy,” pp. 4–5.

- Anthony P Tvaryanas et al., “The Commander’s Wellness Program: Assessing the Association between Health Measures and Physical Fitness Assessment Scores, Fitness Assessment Exemptions, and Duration of Limited Duty,” in Military Medicine Vol. 183, No. 9–10 (1 September 2018) p. e612.

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group, Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy – 2017 Integration for Better Health, National Defence, p. 11.

- Ibid.

- National Defence, Duty with Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada, (Kingston, ON, Canadian Defence Academy, 2009), p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 29.

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group, “Patient-Partnered Care Framework,” 2018.

- Minister of Justice, “Canada Health Act” (Government of Canada, 12 December 2017).; Chief of the Defence Staff, “CFJP 1.0 Military Personnel Management Doctrine,” Canadian Forces Joint Publication (Government of Canada, June 2008), pp. 2–3.

- Minister of Justice, “National Defence Act,” (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 18 December 2018).

- National Defence, “Surgeon General’s Report 2014,” 2014, p. 4.

- Canadian Medical Association, 2013.

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group, “Surgeon General’s Integrated Health Strategy,” p. 2.

- National Defence, “Strengthening the Forces Health Promotion Program,” accessed 3 May 2019, at: <https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/programs/strengthening-forces.html.>

- Minister of Justice, “Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations” (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 23 November 2018); Minister of Justice, “Canada Labour Code” (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 17 March 2019), p. 101.

- Ibid., pp. 1–6.

- National Defence, “Chapter 34: Medical Services,” in Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces, Vol. 2, 2001.

- National Defence, “Chapter 4: Duties and Responsibilities of Officers,” in Queen’s Regulations and Orders, Vol. 1, 2014.

- ndrew Gale and Wayne Pickering, “Force Protection,”in Canadian Military Journal,Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer 2007), pp. 37, 42.

- Chief of the Defence Staff, “Chief of the Defence Staff Guidance to Commanding Officers and Their Leadership Teams” (Canadian Armed Forces, 7 February 2019), pp. 11–47, 11–48.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp. 12–51.

- Ibid., pp. 13–54.

- National Defence, “Chapter 5: Duties and Responsibilities of Non-Commissioned Members,” in Queen’s Regulations and Orders, Vol. 1-Administration, 2015.

- National Defence, Duty with Honour: The Profession of Arms in Canada, p. 14.

- National Defence, “Chapter 4: Responsibilities of CF Leaders,” in Leadership in the Canadian Forces: Conceptual Foundations (Ottawa: Published under the auspices of the Chief of the Defence Staff by the Canadian Defence Academy, Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, 2005), p. 20.

- National Defence, “Ensuring Member Well-Being and Commitment,” in Leadership in the Canadian Forces: Leading the Institution (Kingston, ON: Canadian Defence Academy, Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, 2006), p. 111.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- Alan Okros, “Chapter 7: Becoming an Employer of Choice: Human Resource Challenges within DND and the CF,” in Public Management of Defence in Canada, Craig Stone (ed.), (Toronto: Breakout Educational Network in association with the School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University, 2009), p. 172.

- National Defence, “Ensuring Member Well-Being and Commitment,” p. 17; National Defence, “Chapter 4: Responsibilities of CF Leaders,” p. 20.

- Ibid.

- National Defence, “Chapter 4: Responsibilities of CF Leaders,” p. 24.

- National Defence, “Ensuring Member Well-Being and Commitment,” p. 113.

- Chief of the Defence Staff, “CFJP 1.0 Military Personnel Management Doctrine,” pp. 2–3.

- National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged. Canada’s Defence Policy, 2017.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Field Hygiene and Sanitation,” pp. 1–2.

- The three dimensions of command capability were identified as Competency, Authority and Responsibility (CAR) in Ross Pigeau and Carol McCann, “Re-Conceptualizing Command and Control,” in Canadian Military Journal Vol. 3, No. 1 (2002), p. 57; Ross Pigeau, “Authority, Responsibility and Accountability in Professional Militaries,” 2017, p. 4.

- This self-reported survey of CAF members’ health is administered every four-to-five years. The 2013/14 is the last one from which results were available at the time this article was written.

- National Defence, “Health and Lifestyle Information Survey of Canadian Armed Forces Personnel: 2013/2014,” September 2016, pp. v–vi.

- Ibid., pp. 17–18.

- Ibid., pp. vi–viii.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp. vi–vii.

- Scott’s model is based upon three pillars, which are the regulative, the normative and the cultural-cognitive pillars. See Scott, Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- National Defence, “DAOD 5023-0, Universality of Service,” 13 November 2013.

- National Defence, “DAOD 5023-2, Physical Fitness Program,” 13 November 2013.

- John Geddes, “The Number of Soldiers Citing Medical Reasons for Leaving the Military Is Soaring,” in Macleans, 14 March 2018.

- HLIS has recently been replaced by the CAF Health Survey.

- W. C. Westmoreland, “Mental Health—an Aspect of Command,” in Military Medicine, Vol. 128, No. 3 (1 March 1963), p. 211.

- Scott, Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, p. 64.

- National Defence, “DND and CF Code of Values and Ethics | DND CAF,” 15 July 2013.

- National Defence, “Code of Values and Ethics” (Department of National Defence and Canadian Forces, 2012), pp. A-2/3-A-3/3.

- Alena Mondelli, “Non-Commissioned Members as Transformational Leaders: Socialization of a Corps,” in Canadian Military Journal Vol. 18, No. 4 (2018), p. 30.

- Discussion with Dr. Alan Okros, Canadian Forces College, 22 May 2019.

- Scott, Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, pp. 66–70.

- Pigeau, “Authority, Responsibility and Accountability in Professional Militaries,” p. 3.

- Canadian Army, “Canadian Army Integrated Performance Strategy (CAIPS) – MISSION: Ready,” 24 November 2015.

- Royal Canadian Navy, “RCN Executive Plan 2013-2017” (National Defence, 2013), 4; MARPAC, “MARPAC Health and Wellness Strategy Report Card 2018,” 2018.

- J. Foster and J. H. Vance, “Strategic Initiating Directive - Defence Team Total Health and Wellness Strategy,” 31 January 2017.

- National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged. Canada’s Defence Policy, p. 12.

- Ibid., p. 25.

- Gareth Doherty, “Defence Team Total Health and Wellness Strategic Framework” (HFM-302 Symposium on Evidence-Based Leader Intervention for Health and Wellness, Berlin, Germany, 10 April 2019).

- Discussions with Dr. Gareth Doherty and Ms. Annie Cowham, January and July 2019.

- Moral and Welfare Services, “BALANCE,” accessed 7 May 2019, at: <https://www.cafconnection.ca/National/Programs-Services/For-Military-Personnel/Military-Fitness/FORCE-Program/BALANCE.aspx.>

- Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services, “BALANCE: The Canadian Armed Forces Physical Performance Strategy” (Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 2018), p. 20.

- Ibid., pp. 31, 34, 40–43.

- Ibid., 32.

- Ross Pigeau and Carol McCann, “Establishing Common Intent: The Key to Co-Ordinated Military Action,” in The Operational Art: Canadian Perspectives: Leadership and Command, Allan D. English (ed.), (Kingston, ON: Canadian Defence Academy Press, 2006), pp. 85, 91.

- Walker S.C. Poston et al., “A Content Analysis of Military Commander Messages About Tobacco and Other Health Issues in Military Installation Newspapers: What Do Military Commanders Say About Tobacco?,” in Military Medicine, Vol. 180, No. 6 (June 2015), p. 2.

- Kirk Frady, “Medical Readiness Assessment Tool (MRAT),”24 November 2015.

- Moral and Welfare Services, “FORCE Rewards Program,” accessed 7 May 2019, at: <https://www.cafconnection.ca/National/Programs-Services/For-Military-Personnel/Military-Fitness/FORCE-Program/FORCE-Rewards-Program.aspx.>

- Westmoreland, “Mental Health—an Aspect of Command.”

- Pigeau, “Authority, Responsibility and Accountability in Professional Militaries,” p. 2.

- Perrin H. Long, “Disease and Command Responsibility,” in Military Medicine, Vol. 108, No. 2 (1 February 1951), p. 107.

- Pigeau, “Authority, Responsibility and Accountability in Professional Militaries,” p. 5.